In addition to its terrible human toll, the COVID-19 pandemic also has caused massive disruption in labor markets. In the US alone, over 25 million people lost their jobs during the first wave of the pandemic. While many have returned to work since then, a large number have remained unemployed for a prolonged period of time. The number of long-term unemployed (defined as those jobless for 27 weeks or longer) has surged from 1.1 million to almost 4 million. An important concern is that the long-term unemployed face worse employment prospects, but prior work has provided no consensus on what drives this decline in employment prospects. In this column, we discuss new findings using data on elicited beliefs of unemployed job seekers to uncover the forces driving long-term unemployment.

The long-term unemployed face significantly worse employment prospects

A robust finding in labour economics is that the chances of finding a job decline significantly the longer a person is unemployed (e.g. Machin and Manning 1999). This empirical regularity is referred to as ‘negative duration dependence’. A long-standing question is the extent to which this phenomenon reflects an actual worsening in job seekers’ job prospects – for instance, because their skills deteriorate over time – or rather the shifting composition of the pool of unemployed (e.g. Lancaster 1979, Heckman and Singer 1984). If the unemployed are heterogeneous in their propensity to find a job, those with a higher underlying job-finding rate exit unemployment sooner, while those with a lower job-finding rate make up a progressively larger and larger share of the unemployed. We refer to the former as ‘true’ duration dependence and to the latter as ‘dynamic selection’, or heterogeneity in job finding. While separating the two effects is empirically challenging, the two competing explanations have different implications for labour market policy. True duration dependence may require timely job search incentives or re-training programmes, while heterogeneity would call for the targeting of re-employment efforts.

A novel way of disentangling these effects is to jointly use data on job seekers’ subjective perceptions of their chances of finding a job together with actual job-finding rates at different unemployment durations. As we show in Mueller et al. (2021), the covariance between perceptions and actual job finding helps by uncovering the extent of ex-ante heterogeneity in underlying job-finding probabilities. The remaining duration dependence can then be attributed to a ‘true’ decline in one’s employment prospects.

Here we use data from two novel sources: the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) (Armantier et al. 2017) and the Survey of Unemployed Workers in New Jersey (NJUI) (Krueger and Mueller 2011). Both surveys follow the same respondents over time, enabling us to trace how the same individuals update their perceptions as their unemployment spells progress and when they find employment. The SCE is a monthly online survey of a rotating panel of household heads in the US that started in June 2013, whereas the NJUI is a weekly survey of unemployed workers sampled among recipients of unemployment insurance benefits in New Jersey in the fall of 2009. In the SCE, unemployed job seekers report the probability they expect to find a job within the next three months. In the NJUI, job seekers report the probability that they expect to be re-employed within the next four weeks. The beliefs are elicited up to 12 times (five times) in the SCE (NJUI) for job seekers who remain unemployed.

Job-finding perceptions and actual labour market transitions

Figure 1 shows the average realised job-finding rate at the three-month horizon by different groups of elicited three-month job-finding perceptions. The positive relationship reveals the strong predictive nature of the elicited beliefs – on average, those who report a higher perceived chance of finding a job over the next three months are more likely to find a job within that time frame. A related finding (not shown here) is that job-finding perceptions are also highly predictive of actual job finding rates over the subsequent three months, that is, between month four and six from the time the belief was elicited. This indicates the persistence of potential differences in job finding.

Figure 1 Actual job finding is positively related to workers’ expectations

Source: Mueller et al. (2021).

While highly predictive, the subjective perceptions in our data also display an optimistic bias overall, confirming prior evidence in Spinnewijn (2015). Figure 2 shows averages of the elicited three-month job-finding perception and realised three-month job-finding rate for different ranges of unemployment duration. The figure confirms the strong negative duration dependence in actual job-finding rates. Perceived job-finding probabilities also decline, but at a slower pace. Indeed, while perceptions are roughly in line with realisations at the start of a spell, a gap emerges as the spell continues, with elicited beliefs on average higher than actual job-finding rates – indicating a widening optimistic bias at longer durations. Moreover, we find that job seekers do not revise their beliefs downwards as they remain unemployed, so the observed decline in perceived job finding is fully driven by dynamic selection.

Figure 2 Perceived job finding declines more slowly than actual

Source: Mueller et al. (2021).

True duration dependence or heterogeneity?

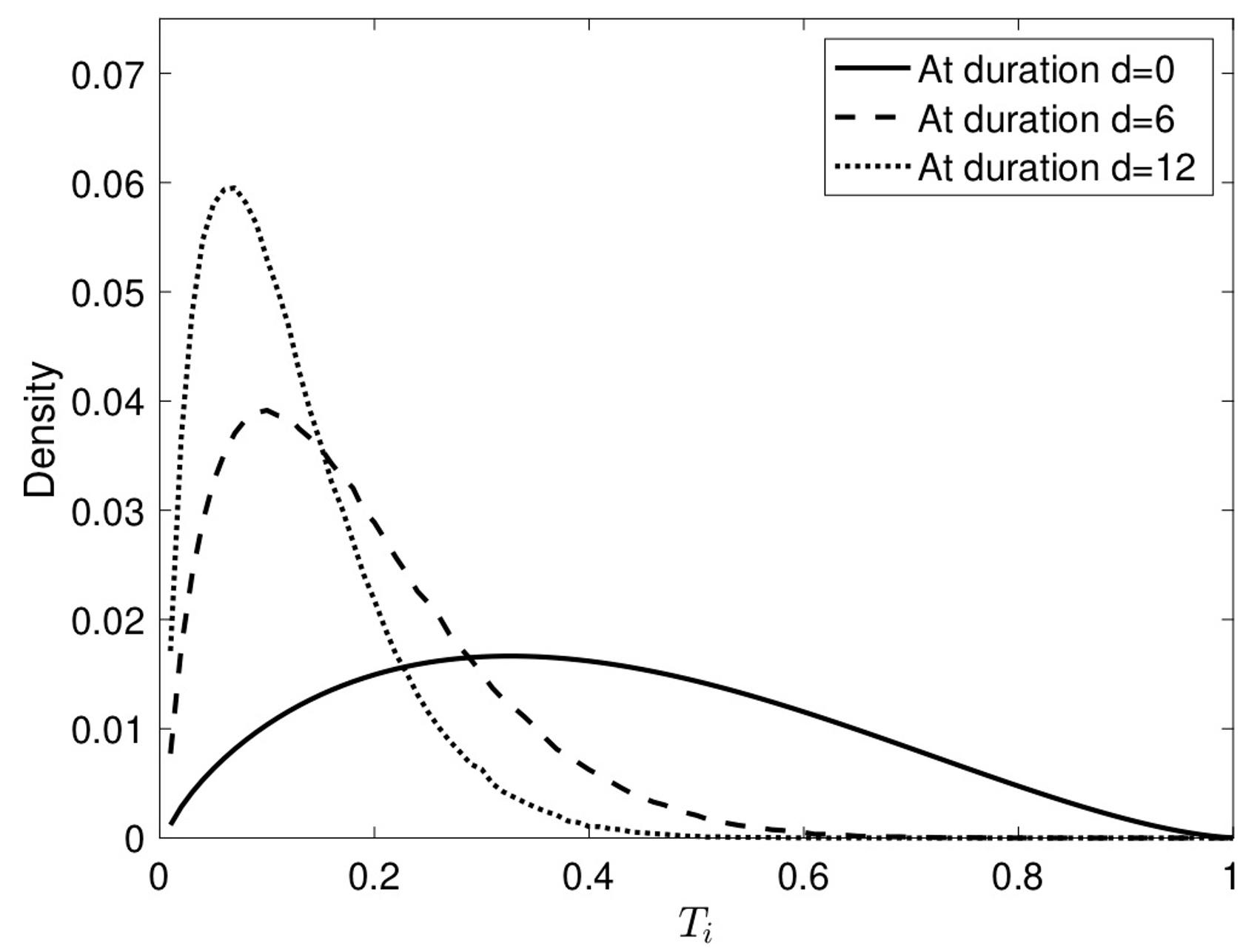

As mentioned above, to disentangle the role of dynamic selection versus ‘true’ duration dependence in explaining the observed decline in actual job finding, we exploit the availability of data on both the individual perceptions and realisations of job finding, together with the ability to follow the same individuals over time. As detailed in Mueller et al. (2021), we do so both in a ‘model-free’ way, looking for a lower bound of the contribution of heterogeneity, and in a statistical model that allows for biases in perceptions and for transitory as well as persistent differences in job finding across job seekers. We find that about 85% of the decline in job-finding rates by duration is due to heterogeneity in job-finding ‘types’, suggesting a limited scope for actual deterioration in one’s employment prospects over the course of an unemployment spell. Figure 3 illustrates this graphically – at an unemployment duration of zero months, the distribution of underlying job-finding probabilities is very dispersed, reflecting the large heterogeneity in types. At higher durations (six or 12 months), the distribution becomes more and more compressed towards lower job-finding propensities, reflecting the effects of dynamic selection in the unemployment pool.

Figure 3 The distribution of job-finding types becomes more compressed at longer durations

Source: Mueller et al. (2021).

Biased beliefs and long-term unemployment

Our analysis underlines the importance of the heterogeneity in unemployed job seekers’ employment prospects. But job seekers underestimate these differences. Those with low underlying employment prospects tend to be overly optimistic and vice versa. The corresponding dynamic selection drives the optimistic bias among the long-term unemployed. Importantly, the under-response of beliefs can itself induce a higher incidence of long-term unemployment. Job seekers with worse employment prospects discard too many potential job offers, as they hold out for the possibility of a better offer in the future. Workers with better prospects do the opposite. The differences in re-employment thus get magnified through the job search behaviour. Incorporating the biases in beliefs into a model of job search behaviour, we find that it may raise the incidence of long-term unemployment by 10% – a significant amount.

Overall, these findings suggest that the design of unemployment policies should take the heterogeneity across workers losing their jobs seriously due to the resulting selection into long-term unemployment. Improving job seekers’ information about their employment prospects may further help to lower the high incidence of costly long-term unemployment.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. A version of this column originally appeared in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Liberty Street Economics blog.

References

Armantier, O, G Topa, W van der Klaauw and B Zafar (2017), “An Overview of the Survey of Consumer Expectations”, Economic Policy Review 23(2): 51-72.

Heckman, J J and B Singer (1984), “The Identifiability of the Proportional Hazard Model”, The Review of Economic Studies 51(2): 231-241.

Krueger, A B. and A I Mueller (2011), “Job Search, Emotional Well-Being, and Job Finding in a Period of Mass Unemployment: Evidence from High-Frequency Longitudinal Data”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1(1): 1-70.

Lancaster, T (1979), “Econometric Methods for the Duration of Unemployment”, Econometrica 47(4): 939-56.

Machin, S and A Manning (1999), “The Causes and Consequences of Longterm Unemployment in Europe”, in O C Ashenfelter and D Card (eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics Vol. 3, Part C, Elsevier, pp. 3085-3139.

Mueller, A I, J Spinnewijn and G Topa (2021), "Job Seekers' Perceptions and Employment Prospects: Heterogeneity, Duration Dependence, and Bias", American Economic Review 111(1): 324-63.

Spinnewijn, J (2015), “Unemployed but Optimistic: Optimal Insurance Design with Biased Beliefs”, Journal of the European Economic Association 13(1): 130-167.