In the 21st century, the world has witnessed a revolution in information and communication technology (ICT). According to the International Telecommunications Union, internet penetration (the number of internet users per capita) around the world has increased from 7% in 2000 to 48% in 2017. While the internet – and especially the fast internet – has brought substantial economic benefits to both developed and developing countries (see, for example, the recent study by Hjort and Poulsen 2019 describing the large positive impact of the arrival of fast internet in 12 African countries), there is an ongoing debate on the political implications of the internet’s expansion. Diamond and Plattner (2010) brand the internet a “liberation technology” that helps to spread critical information about non-democratic governments and to coordinate protests. The internet, however, is also used by autocrats for propaganda and surveillance (Mitchell et al. 2019, Morozov 2011). And opportunistic politicians do take advantage of the internet to disseminate fake news and to misinform voters (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017, Vosoughi et al. 2018, Tufekci, 2018).

In a new paper (Guriev et al. 2019), we study the political effects of internet access in a global setting. We explore the expansion of internet access due to the rollout of third generation (3G) mobile networks around the world during the last decade. In 2007, only 4% of the world’s population lived in areas covered by 3G networks; by 2018, this number had reached 69%. Using the data on the availability of 3G networks in 2,232 subnational regions of 116 countries across all continents during the period 2008-17, we analyse the internet’s impact on political attitudes and beliefs collected by the Gallup World Poll.

We find that the expansion of 3G networks increases internet usage, decreases the public’s confidence in the national government, and increases the perception that the government is corrupt. The magnitudes are substantial. An increase of regional 3G coverage from zero to full coverage of a region reduces confidence in the government by 6% on average (relative to the mean of 51%) and decreases the perception that the government is not corrupt by 4% (the mean is 23%).

We show that these effects are specific to political attitudes and cannot be explained by the internet making people generally more negative and less optimistic about their lives. There is no effect of 3G on life satisfaction, or the expectations of life satisfaction in the future. We also verify that it is access to the internet rather than other aspects of ICT that reduces the government approval by studying the expansion of the second generation (2G) mobile networks. Unlike 3G that allows browsing the web on a smartphone, 2G technology only gives access to mobile telephony and texting. In sharp contrast to our results for 3G, we find that the expansion of 2G networks, if anything, increases the support of the government. Apparently, the public appreciates the increase in connectivity and attributes the improvements in digital infrastructure to government performance, but access to the internet makes the public less positive about their governments.

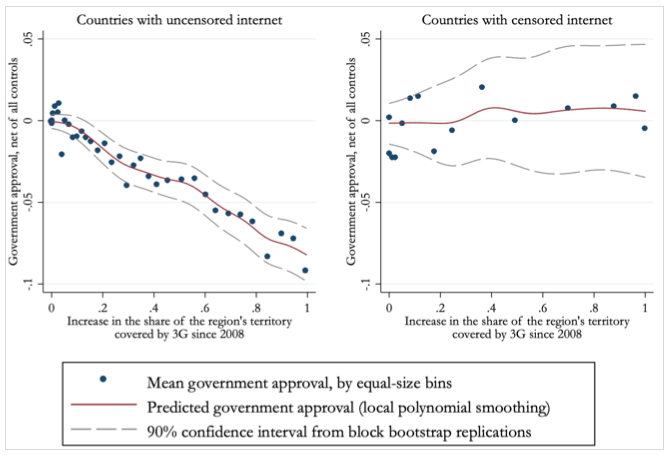

Importantly, mobile internet decreases confidence in government only when the internet is not censored (these findings are illustrated by Figure 1). This result is consistent with the view that censorship of the internet is effective. Furthermore, the effect of the internet on confidence in government is particularly large when traditional media is censored while the internet is free, implying that the public uses the internet to get political news when there are no other sources of political information. Consistent with this explanation, we find that the effect of the internet is stronger in non-OECD countries than in OECD countries, and it is stronger for rural residents, as well as for less educated, poor, and unemployed individuals.

Figure 1 The relationship between the expansion of 3G networks and the change in government approval in countries with and without online censorship

We also find direct support for the information channel, namely in that the internet is an important source of political information for voters. In particular, we find that the number of actual incidents of government corruption is more strongly associated with higher perceptions of corruption when there is access to mobile internet.

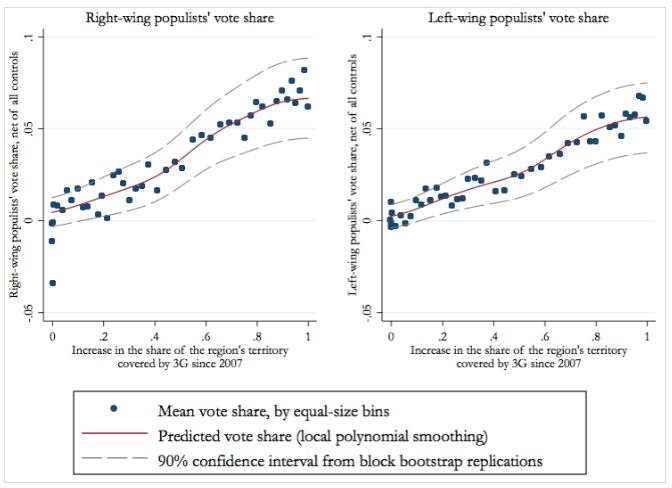

Taken together, the results above suggest that uncensored internet can indeed be a powerful tool of political accountability. On the other hand, we also find that mobile internet empowers anti-establishment politicians, increasing the vote shares of right-wing and left-wing populists. We demonstrate this using data for 87 elections that took place between 2007 and 2018 in 30 European democracies, for which there is a conventional classification of political parties into populist and non-populist. The magnitudes are again rather large – an expansion of 3G coverage in a subnational region from zero to full coverage increases the vote share of left-wing populists by 6% and the vote share of right-wing populists by 7% (as illustrated on Figure 2). These results imply that, as well as being a source of political information for the population about their incumbent government, the internet helps anti-establishment politicians connect to voters, whatever their political agenda.

Figure 2 Expansion of 3G and voting for right-wing and left-wing populists in Europe

Overall, there is a strong evidence that the expansion of 3G internet has had important political implications. One cannot, however, draw a one-sided picture of the effect mobile internet has had on politics. When online content is uncensored, mobile internet helps disseminate critical information about government. This leads to both the decrease in confidence in government, as we find, and increase in protest activity, as found by Manacorda and Tesei (forthcoming). In part due to the disillusionment of voters with political elites that we describe, in part due to lowering the cost of reaching out to voters for political newcomers, anti-establishment politicians seem to benefit politically from the internet expansion. In particular, our results imply that the spread of mobile internet has been one of the major drivers of the recent rise of populism in Europe.

References

Allcott, H, and M Gentzkow (2017), “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236.

Diamond, L, and M F Plattner (2010), “Liberation Technology”, Journal of Democracy, 21, 69–83.

Guriev, S, N Melnikov, and E Zhuravskaya (2019), “3G Internet and Confidence in Government”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 14022.

Hjort, J, and J Poulsen (2019), “The Arrival of Fast Internet and Employment in Africa”, American Economic Review, 109 (3), 1032-1079.

Manacorda, M, and A Tesei (forthcoming), “Liberation Technology: Mobile Phones and Political Mobilization in Africa”, Econometrica.

Mitchell, A, J Gottfried, S Fedeli, G Stocking, and M Walker (2019), “Many Americans Say Made-Up News Is a Critical Problem That Needs To Be Fixed”, Pew Research Center.

Morozov, E (2011), “The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom”, Public Affairs, New York.

Tufekci, Z (2018), “How social media took us from Tahrir Square to Donald Trump”, MIT Technology Review.

Vosoughi, S, D Roy, and S Aral (2018), “The spread of true and false news online”, Science, 359, 1146–1151.