A defining feature of the economic shock from the Covid pandemic is its asymmetry across sectors, contributing to a sharp recession (Guerrieri et al. 2020). As economies contracted in the early phase of the pandemic, sales and employment fell sharply in particular sectors (Bloom et al. 2020). As the recovery proceeds, a key question is whether demand will return to the same places where it fell, or whether some firms and sectors will lose demand and thus shed jobs permanently. In the latter case, productive factors will need to move from shrinking firms and sectors to growing ones. This reallocation may prove to be costly, as firms and workers rebuild human, physical and organisational capital.

Reallocation is often studied in retrospect rather than in real time, since there are often lags before data on jobs and sales become available. To overcome this limitation, we make use of timely data from two parallel business surveys for the UK and US. For the UK, we use survey data collected by the Bank of England, Nottingham and Stanford Universities through the monthly Decision Maker Panel (DMP) survey, a large and representative online panel of UK firms established in 2016 (see Altig et al., 2020b, Bloom et al. 2020 and Bloom et al. 2021 for previous posts that use these data). For the US we use the Atlanta Fed/Chicago Booth/Stanford Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU) (Altig et al. 2020a, 2020b). Both surveys collect data on actual sales and employment, and on businesses’ expectations for both variables at a one-year look-ahead horizon. Thus, we can track the effects of the pandemic thus far and business expectations about its future evolution in real time.

Covid-19 is a major reallocation shock

We construct standard measures of cross-firm resource reallocation, namely, the excess reallocation rates for jobs and sales (Davis and Haltiwanger 1992). Excess reallocation quantifies the amount of firm-level employment or sales changes over and above the amount required to accommodate the net change in aggregate employment or sales, usually focusing on past changes reported in administrative data.1 We extend this measure by constructing the expected 36-month reallocation rate that uses data looking back 24 months and looking ahead 12 months, dating the series by when the data were collected. The 36-month reallocation rate we compute for July 2021, for example, covers the entire period from mid-2019 to mid-2022. To do so, we first add an individual firm’s realised employment growth in the 24 months prior to a given survey to its expected sales growth looking 12 months ahead. Then, we aggregate those growth rates with appropriate weights (following Davis and Haltiwanger 1992) to obtain the 36-month reallocation rate. We focus on a 36-month window in this post to ensure that the lookback horizon begins before the pandemic, and thus captures all the reallocation that has taken place since the start of the pandemic, plus what is expected over the next year.

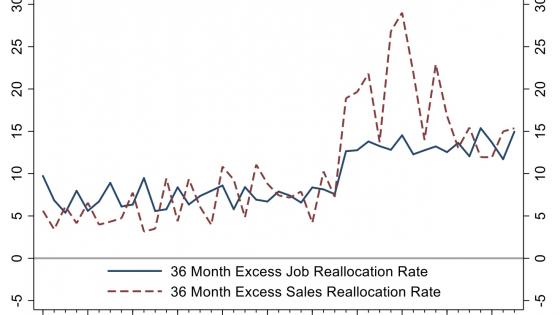

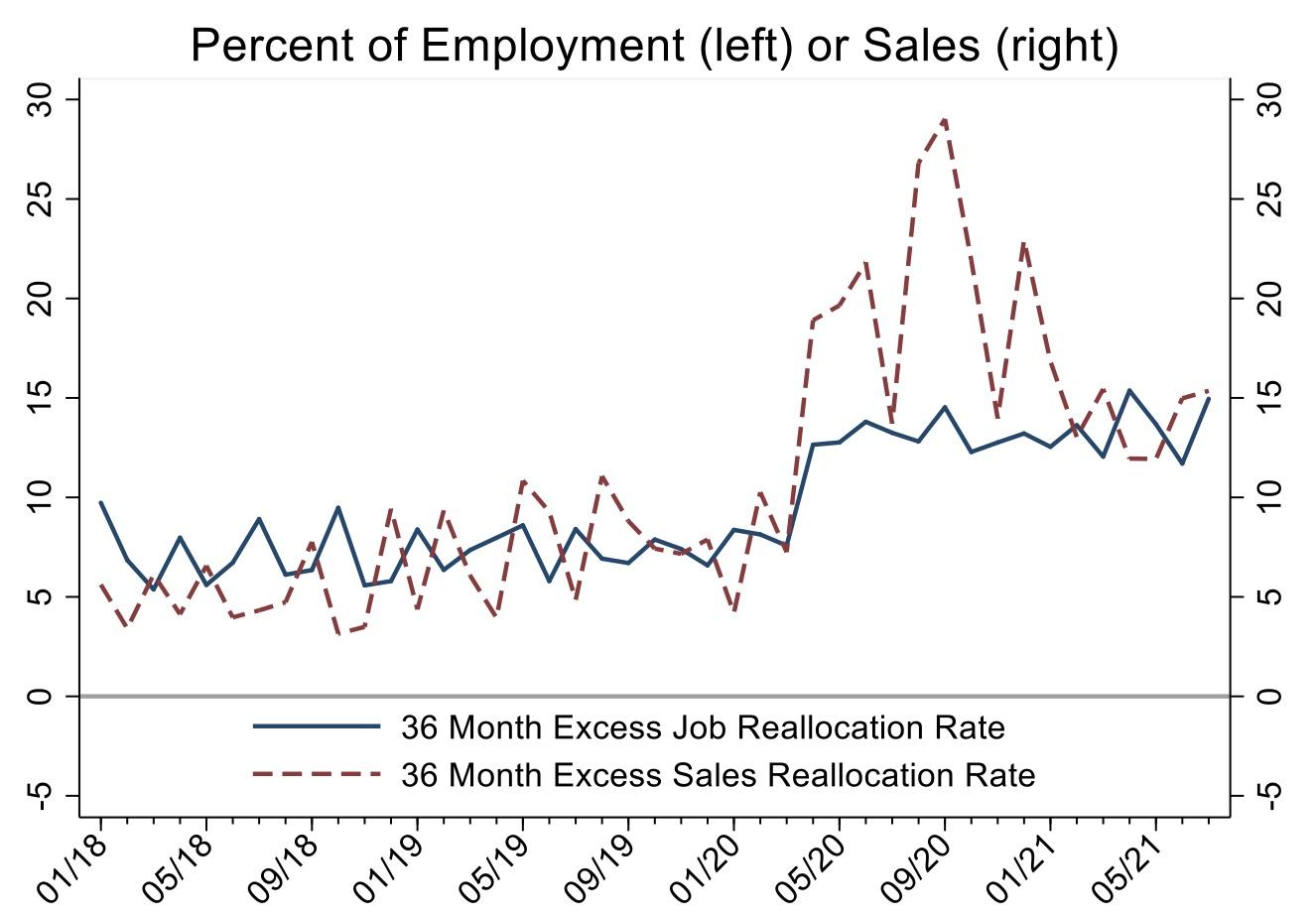

Figure 1 shows our 36-month job and sales reallocation series for the UK and the US. Since the inception of the Covid pandemic, excess job reallocation rates have approximately doubled in both countries. Excess reallocation rates for sales revenue have increased even more, particularly in the UK. We suspect that the UK’s large furlough scheme, which prevented job destruction via significant payroll subsidies, limited the rise in job reallocation. Our latest data, from July 2021, show that job and sales revenue reallocation remain well above pre-pandemic levels, so firms expect the reallocative impact of Covid-19 to persist at least as far as the middle of next year. This confirms the key result from Barrero et al. (2021), who argue the Covid reallocation shock is persistent based on SBU data as of December 2020.

Figure 1 Excess reallocation rates have risen sharply in the UK and US

a) UK

b) US

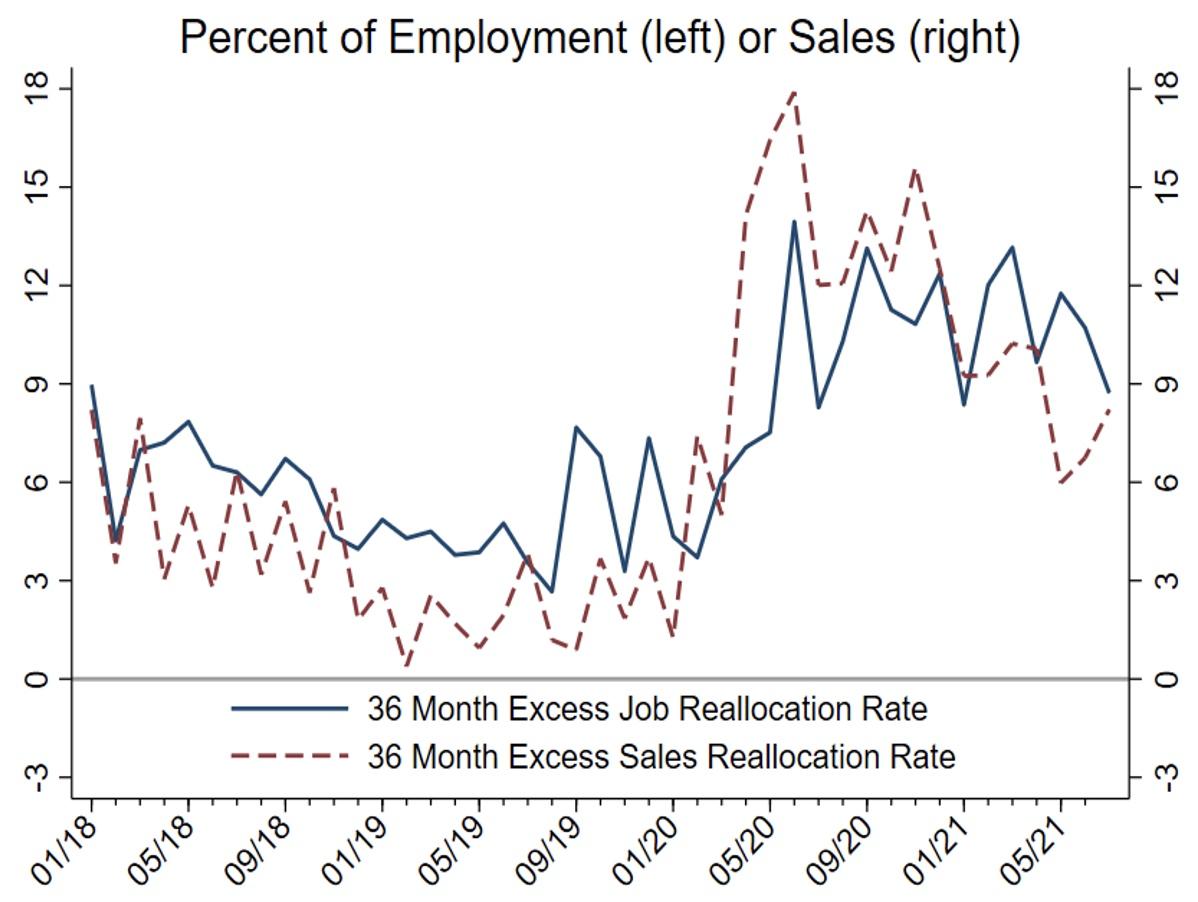

To get a sense of the magnitude of the reallocative effects of Covid, we examine how the amount of reallocation in the UK during this period compares to the amount seen during the global financial crisis (GFC), the last episode of significant reallocation. We construct three-year backward-looking job and sales reallocation series for 2005 to 2019 using annual company accounts data (which are available for the UK but not the US) and plot them in Figure 2. We then use two-year look-back and one-year expectations data from the DMP data to obtain a more recent series.2

Looking at Figure 2, we can see that cross-firm job and sales reallocation rates have been stable or falling in the UK over the past 15 years. During the Covid pandemic, sales reallocation rose more than during the GFC, although job reallocation rose less. These facts are consistent with the larger GDP but smaller unemployment response in the UK during Covid, and again point to the role of furlough schemes in reducing the extent of employment reallocation.

Figure 2 For the UK, Covid has led to higher rates of excess sales reallocation than in the GFC, but excess job reallocation is lower than in the GFC

More of this excess reallocation will take place across sectors

Reallocation can take place between industrial sectors, for example as the economy industrialises or deindustrialises, or between firms in the same sector, as resources flow from less to more efficient firms producing similar goods or services (Baqaee and Farhi 2020).

Historically, the between-sector component typically accounts for only 10 to 20% of excess reallocation (Davis and Haltiwanger 1999), but the unusual nature of the Covid shock, with some sectors practically shut down completely, raises the question of whether between-sector reallocation dominates the surge we see in Figures 1 and 2. This question is important because it is harder for factors to move across sectors than between firms in the same sector, so more between-sector reallocation could mean a slower, more protracted recovery.

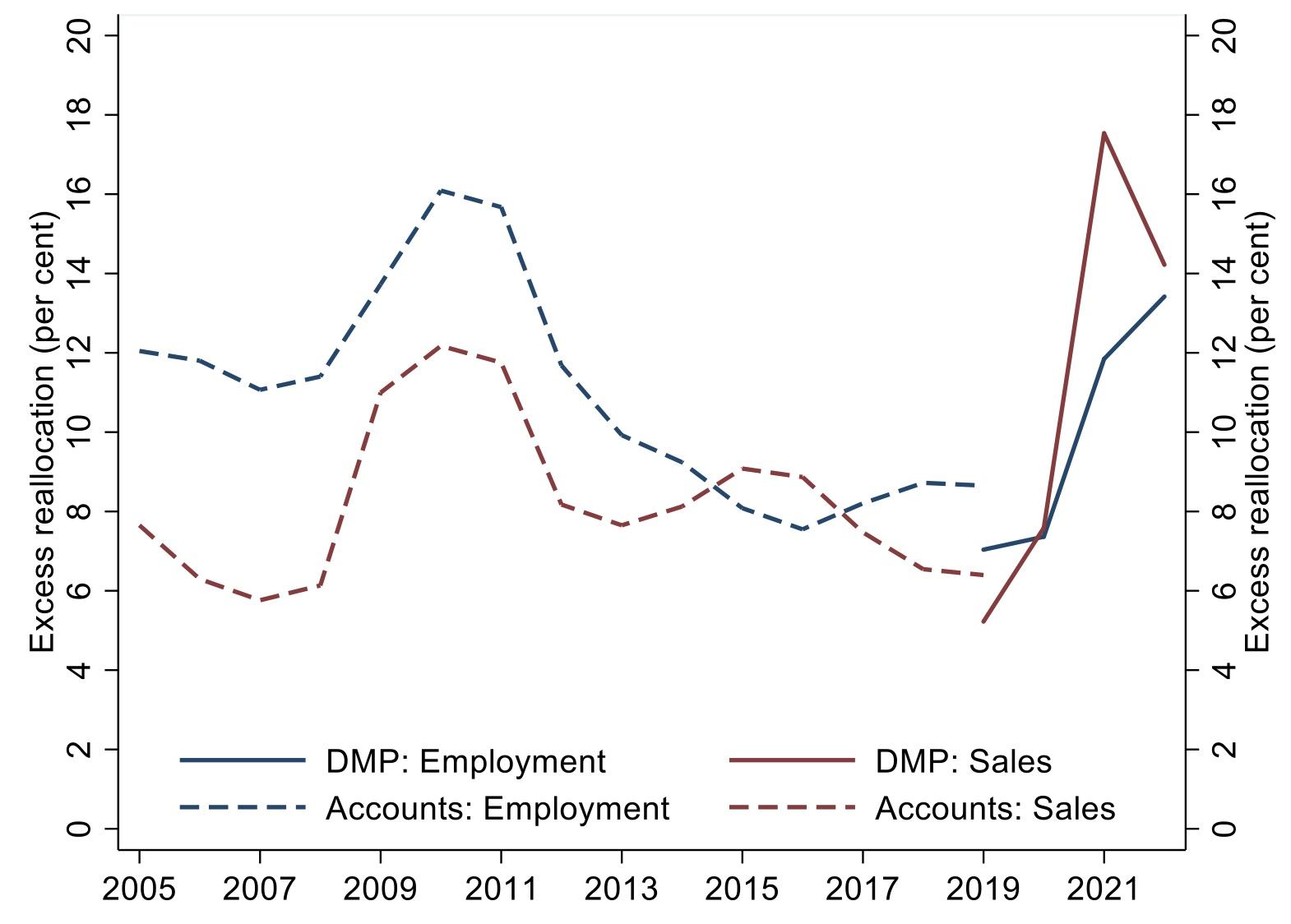

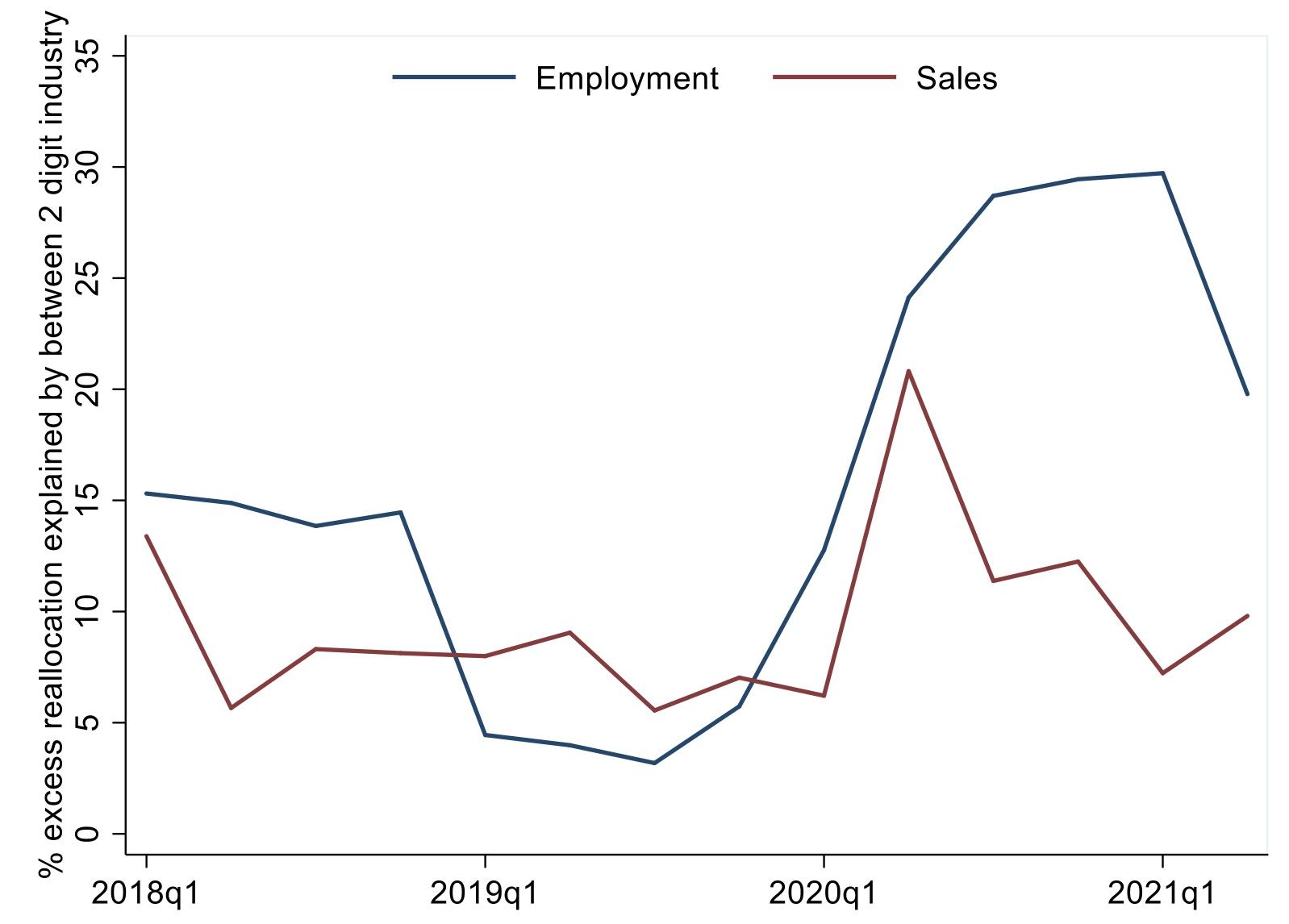

Using the decomposition of Davis and Haltiwanger (1992), Figure 3 shows how much of the 36-month reallocation in our UK data comes from reallocation between two-digit industries. We focus on the UK because we have a larger sample with over 3000 firms, which is useful for distinguishing the between and within-sector components of excess reallocation. As the pandemic unfolded, job and sales reallocation rose sharply (Figures 1 and 2).3 Figure 3 shows that the between-industry share of excess job reallocation more than doubled relative to its pre-Covid average of around 10% in 2018 and 2019. The between-industry share of excess sales reallocation also rose, but more modestly. Still, the between-industry component of excess reallocation amounts to less than one-third of the total, implying a dominant role for the within-industry component.

Figure 3 The between-industry component of excess reallocation rose in reaction to the pandemic, but most excess reallocation continues to occur within industries

Implications

Other things equal, an increase in factor reallocation raises the potential for a mismatch between the kinds of capital and labour firms demand and the kinds the economy can readily supply. Related, the time and expense required to reallocate jobs and workers can raise frictional unemployment. For both reasons, the reallocative aspects of the COVID shock may slow the economic recovery. By depressing potential output for a period of time, they might also increase inflationary pressures at any given level of demand. Although the recent uptick in inflation in both the UK and US may reflect temporary factors such as higher commodity prices and bottlenecks, mismatch could be contributing as well. The persistence of this type of inflationary pressure depends on how quickly the economy adjusts to the reallocative aspects of the COVID shock, to effects on inflation expectations, and on the response of monetary policymakers.

References

Altig, D, J M Barrero, N Bloom, S J Davis, B Meyer, and N Parker (2020a), “Surveying Business Uncertainty”, Journal of Econometrics, forthcoming.

Altig, D, S Baker, J M Barrero, N Bloom, P Bunn, S Chen, S J Davis, J Leather, B Meyer, E Mihaylov, P Mizen, N Parker, T Renault, P Smietanka, and G Thwaites (2020b), “Economic uncertainty in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic”, VoxEU.org, 23 July.

Barrero, J M, N Bloom, S J Davis, and B Meyer (2021), “COVID-19 is a Persistent Reallocation Shock’, AEA Papers and Proceedings 111: 287-91.

Baqaee, D R, and E Farhi (2020), “Productivity and misallocation in general equilibrium”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 105-163.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, S Chen, P Mizen, G Thwaites and P Smietanka (2020), “Coronavirus expected to reduce UK firms’ sales by over 40% in Q2”, VoxEU.org, 20 May.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, S Chen, P Mizen, G Thwaites and P Smietanka (2021), “The impact of Covid-19 on productivity”, VoxEU.org, 18 January.

Davis, S J, and J Haltiwanger, (1992), “Gross job creation, gross job destruction, and employment reallocation”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(3): 819-863.

Davis, S J, and J Haltiwanger (1999), “Gross job flows”, Chapter 41 in Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 3, Part B, pp. 2711-2805.

Guerrieri, V, G Lorenzoni, L Straub, and I Werning, (2020), “Macroeconomic implications of COVID-19: Can negative supply shocks cause demand shortages?”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

Endnotes

1 The excess job reallocation rate is the sum of absolute employment changes across firms (gross reallocation) less the absolute value of the aggregate net employment change, expressed as a percentage of total employment. This netting is especially important when aggregate employment changes sharply, as in the pandemic recession. The excess sales reallocation rate is defined analogously.

2 Unlike in Figure 1, we date the DMP data by the end of the three-year window in Figure 2, so as to be consistent with the timing of the three-year backward looking measure constructed from company accounts.

3 The chart shows contributions to excess reallocation accounted for by reallocation between 52 2-digit industries. We grouped some smaller industries to ensure that all industries have at least 10 observations in each period. The remaining share is accounted for by excess reallocation within industries.