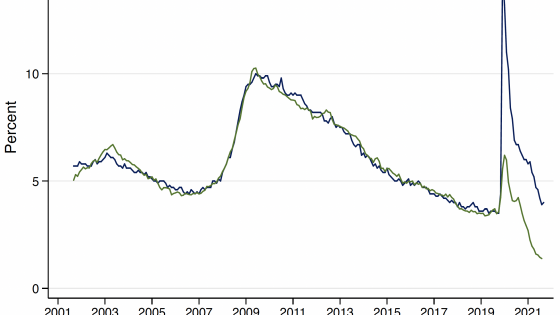

The US economy is recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic with a robust job market and high inflation. With the highest inflation in nearly 40 years, the Federal Reserve considers the tight labour market (Summers 2022) as a key driver of surging prices along with supply shortages and bottlenecks, the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, and lingering COVID-19 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2022). To fight inflation, the Federal Reserve has been raising rates, and a main goal of raising interest rates is to reduce inflation by cooling the labour market, primarily by reducing new wage postings (Powell 2022). However, risk of a global recession in 2023 has been rising because central banks across the world are simultaneously raising interest rates in response to inflation.

At the end of WWI, the US was experiencing strong growth and unruly inflation driven in part by expansionary fiscal policy and accommodative monetary policy – a macroeconomic state comparable to that of the US in 2022. To tame inflation in 1920, the Federal Reserve raised rates in a bid to loosen tight labour markets. In December 1919, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York raised its discount rate, which was the central bank’s main monetary policy tool back then, to 4.75%. In January 1920, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and other reserve banks raised their discount rates to 6%. In June 1920, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York raised its discount rate to 7%. Following the Fed’s rate increases, the US economy went into a recession, often referred to as the depression of 1920-1921.

The rate hikes in 1920 can be considered as an ‘experiment’ of a change in monetary policy regime (Huizinga and Mishkin 1986) and shed light on the trade-off between taming inflation and risk of recession. Previous studies have investigated how changes in aggregated demand affected aggregate output around the recession of 1920-1921 (Romer 1988, Rockoff 2004). With newly constructed detailed labour market data, in our recent work we investigate labour market dynamics around the monetary policy tightening (Anderson and Chang 2022).

The recession of 1920-1921 following the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes

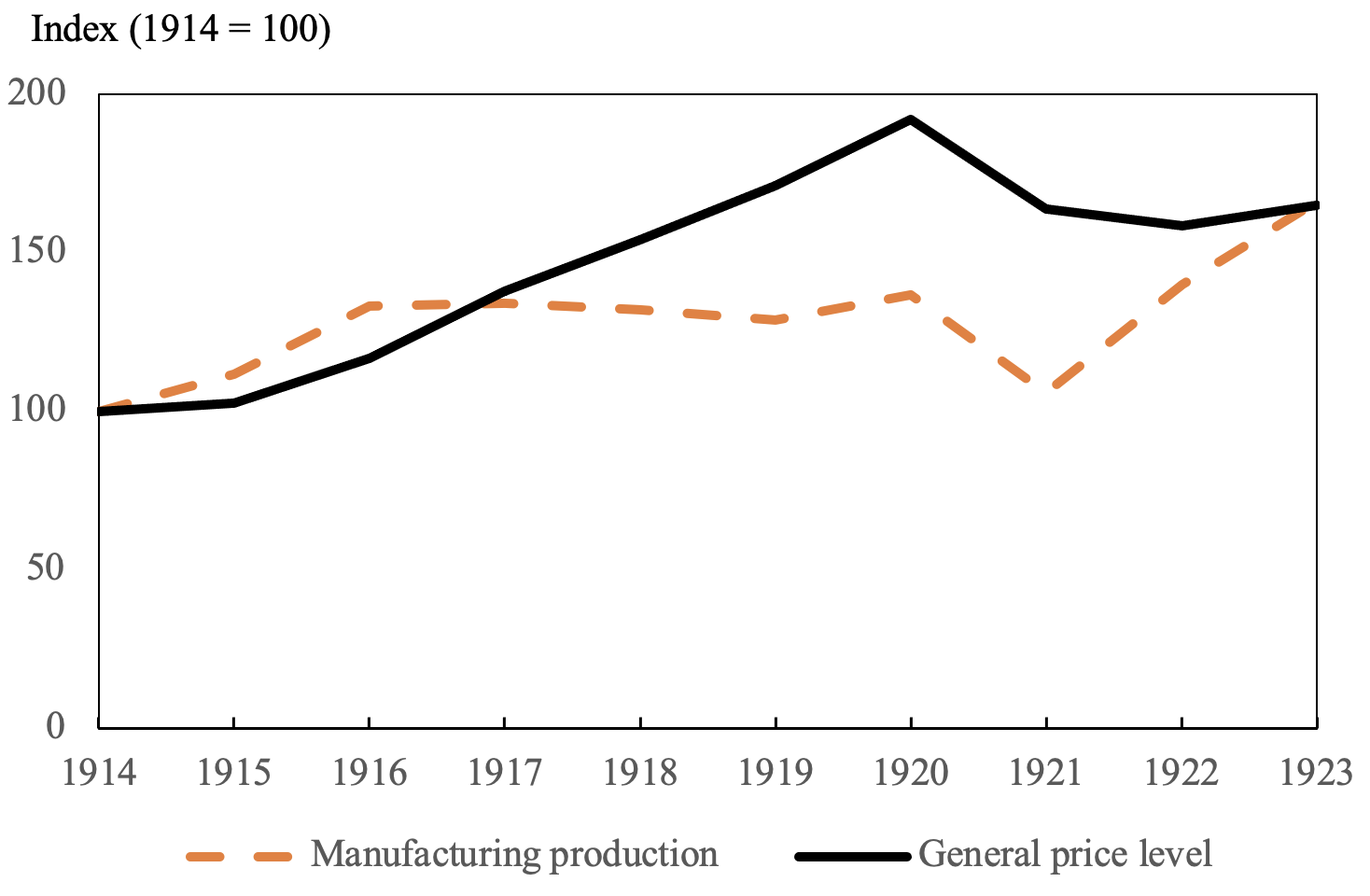

As the Federal Reserve Banks were increasing rates, a sharp, deep recession began in 1920 lasting until 1921. Panel A of Figure 1 plots manufacturing production and price levels over 1914-1923. During the recession, manufacturing production declined by 22%, and the unemployment rate rose by 11%, from 5.2% to 11.3%. Price levels declined as well. However, the economy rebounded quickly and experienced a long economic expansion.

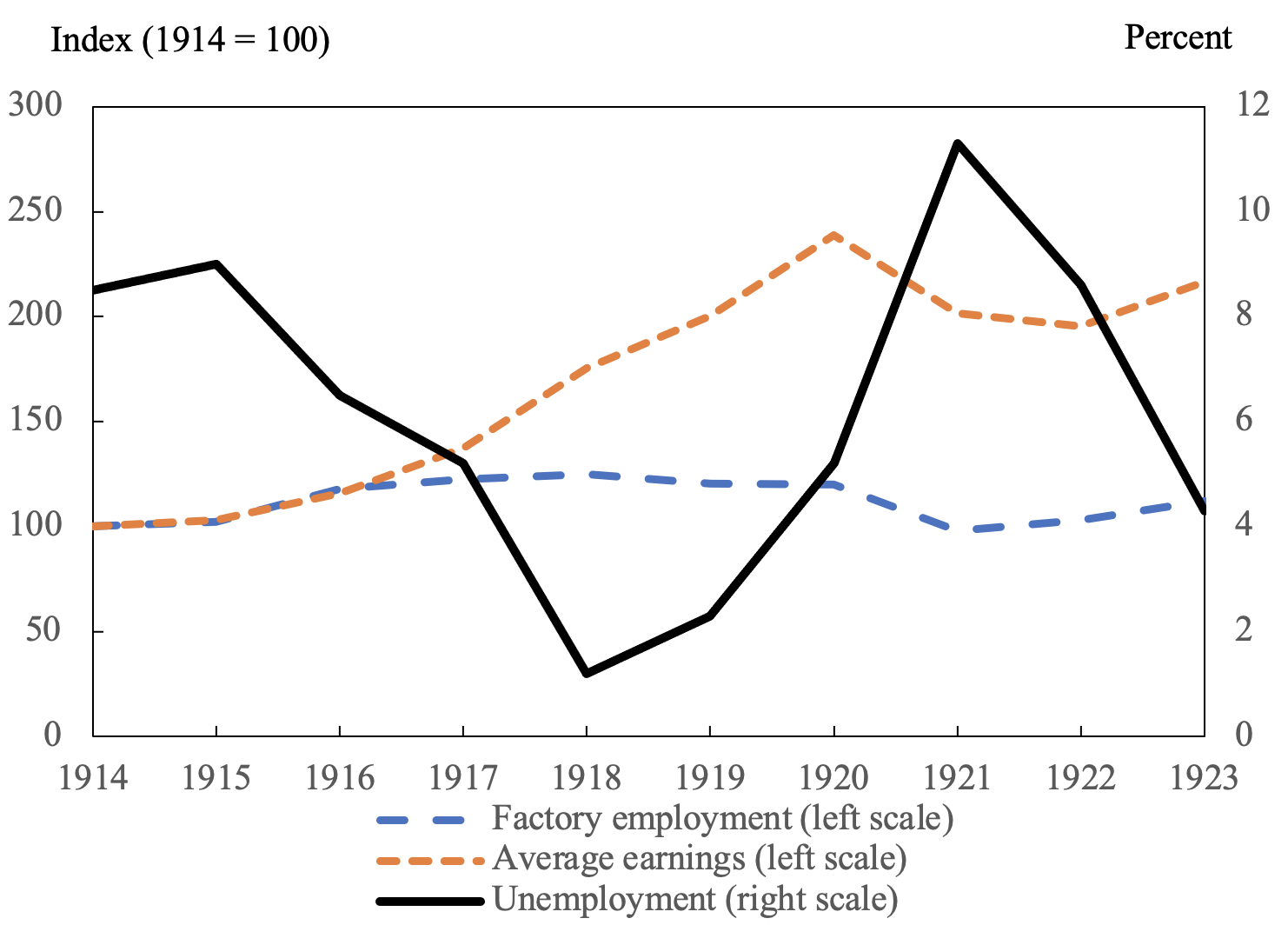

Panel B of Figure 1 plots the unemployment rate, factory employment, and average weekly earnings. During WWI, labour demand peaked, and the unemployment rate fell to just 1.2%. Unemployment rose slowly afterward, peaking at 11.4% at the height of the recession in 1921. Factory employment also fell slightly. The most notable feature of the labour market is the magnitude of changes in average weekly earnings. The average weekly earnings rose by 73% between 1917 and 1920 but plunged by 15% between 1920 and 1921. These patterns suggest that the Fed’s rate hikes succeeded in slowing wage increases, but also raised the unemployment rate.

Figure 1 Macroeconomic indicators

Panel A

Panel B

Sources: Manufacturing Production, Price Level, Factory Employment, Average Earnings: NBER Macrohistory, Unemployment: Banking and Monetary Statistics.

Labour market tightness during WWI and the postwar recession of 1920-1921

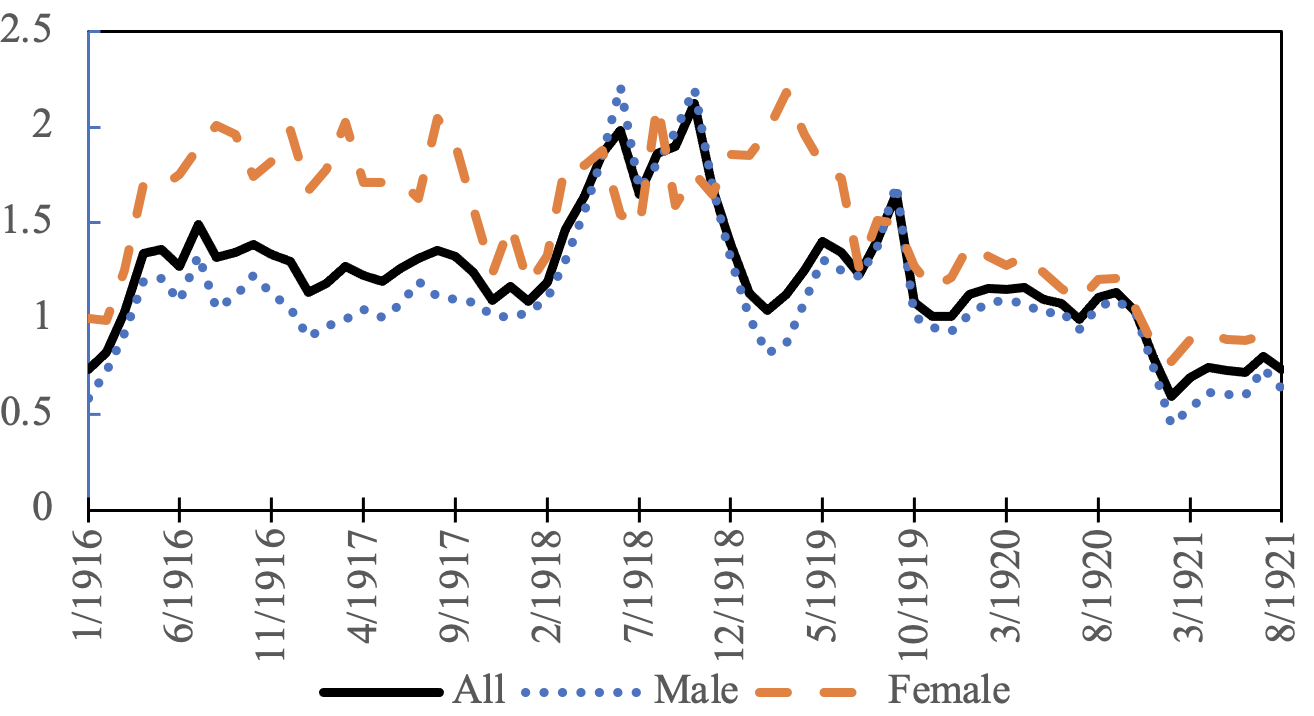

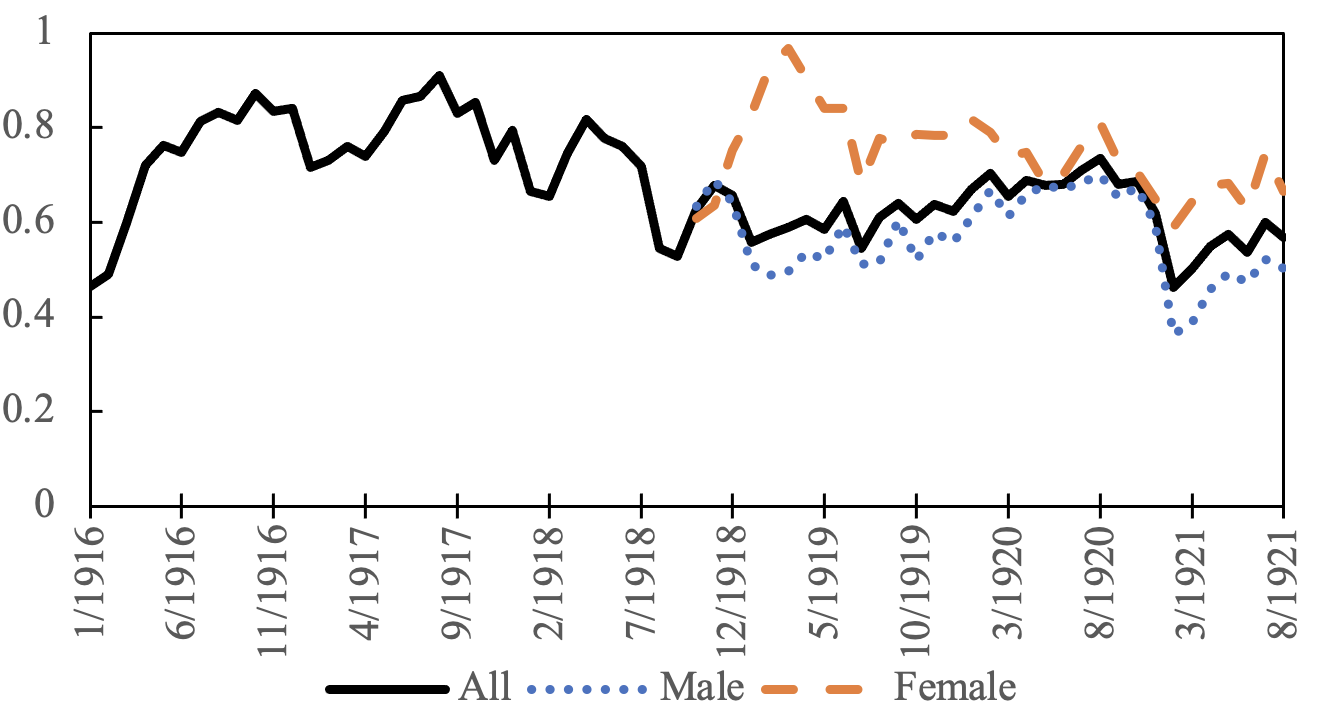

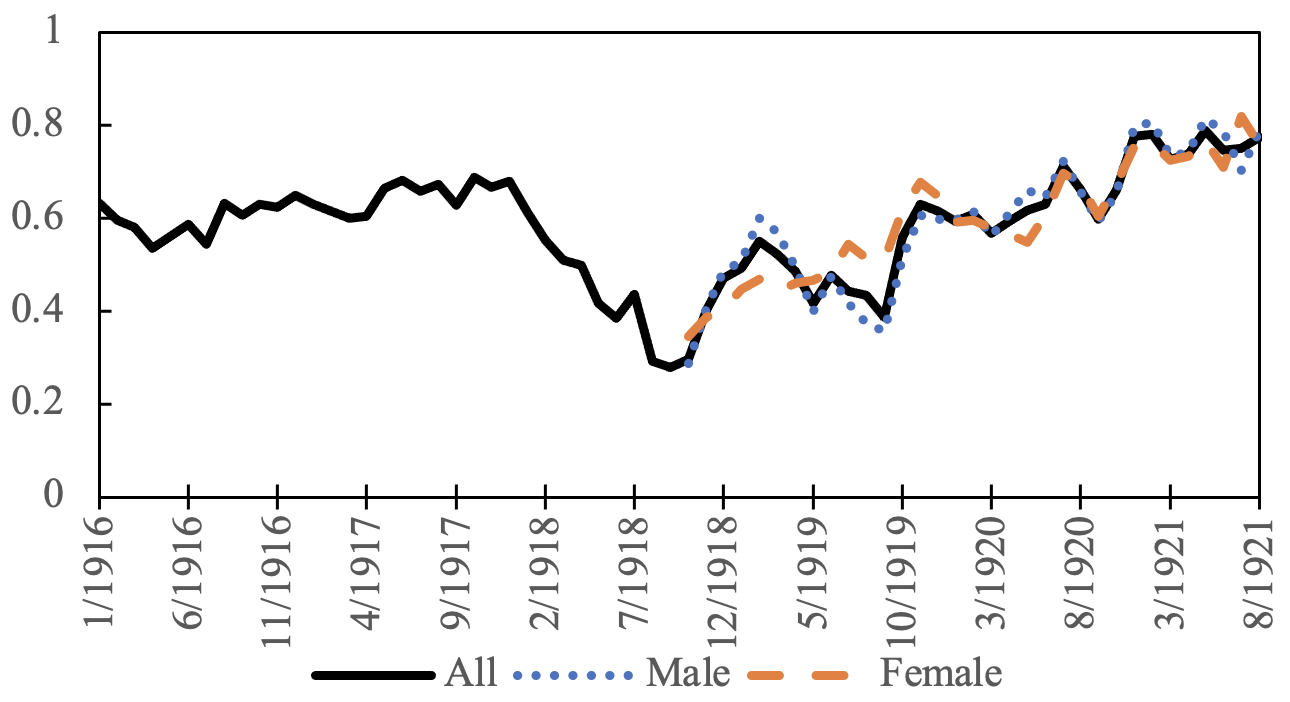

Using a newly constructed data set from public employment offices, we measure job-finding rates, job-filling rates, and labour market tightness from the end of WWI to the recession of 1920-1921 to investigate the labour market dynamics in detail. Figure 2 plots labour market tightness, the job-finding rate, and the job-filling rate. In Panel A, we plot the vacancies to unemployed from January 1916 to August 1921. It shows that the labour market was very tight in the 1910s. Labour market tightness fell briefly after the end of WWI but rebounded quickly afterward. The tight labour market resulted in high employment and rising real wages. When the US economy reached a peak in January 1920, labour markets were tight. Importantly, labour market tightness fell sharply in the middle of 1920, about two quarters after the tightening of monetary policy.

Figure 2 Labour market tightness, job-finding rate, and job-filling rate, New York

Panel A: V-U Ratio

Panel B: Job Finding Rate

Panel C: Job Filling Rate

Note: “Registrations” was used for the number of job seekers; “Help Wanted” was used for the number of job vacancies; and “Placed” was used for the number of new matches.

Source: Labor Market Bulletin.

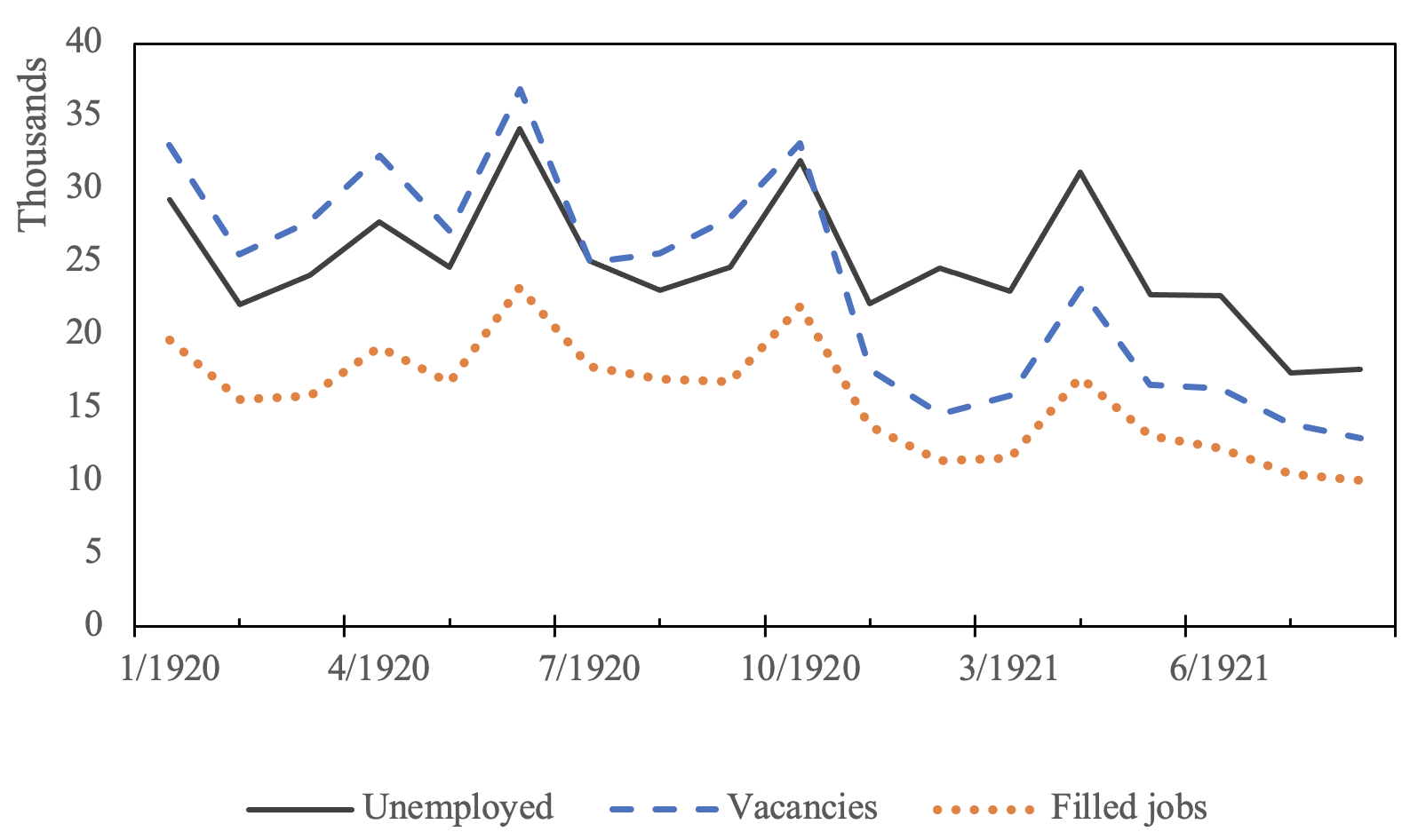

We show that labour market dynamics were largely driven by labour demand rather than labour supply during this period. In Figure 3, we plot the number of workers looking for jobs and vacancies and examine whether a decline in labour demand led to a decline in the number of job openings or an increase in layoffs. If a demand-supply imbalance in the labour market was driven by a decline in the number of job openings, the number of workers looking for jobs would be relatively stable. On the other hand, if the imbalance was driven by an increase in layoffs, we would see a rise in the number of workers looking for jobs. We find that the supply of workers was relatively stable, but the number of job openings declined sharply, falling below the number of workers looking for jobs. By mid-1920, labour markets became much less tight because of large contractions in labour demand. We also find that the decline in labour market tightness was driven by a decline in the large number of job openings during the recession of 1920-1921. These patterns imply that a large decline in job openings derailed the labour market, raising the unemployment rate.

Figure 3 Unemployed, vacancies, and filled jobs, 1920:M1-1921:M8

Sources: Labor Market Bulletin.

We also show that the recession following the monetary policy tightening had an uneven effect across industries. We show that a collapse in labour demand from manufacturing resulted in an imbalance between labour demand and supply. During WWI, manufacturing and other industries that mobilised for war production naturally experienced the worst labour shortages. Then following the end of WWI, labour demand from these manufacturing sectors declined. In contrast, labour demand from retail and other non-manufacturing sectors increased. Even though the importance of manufacturing and other industrial sectors decreased after the end of WWI, jobs from these sectors still accounted for more than a quarter of total jobs during the recession of 1920-1921. This implies that a large contraction in labour demand from these sectors during the recession had a large effect on the labour market at the aggregate level.

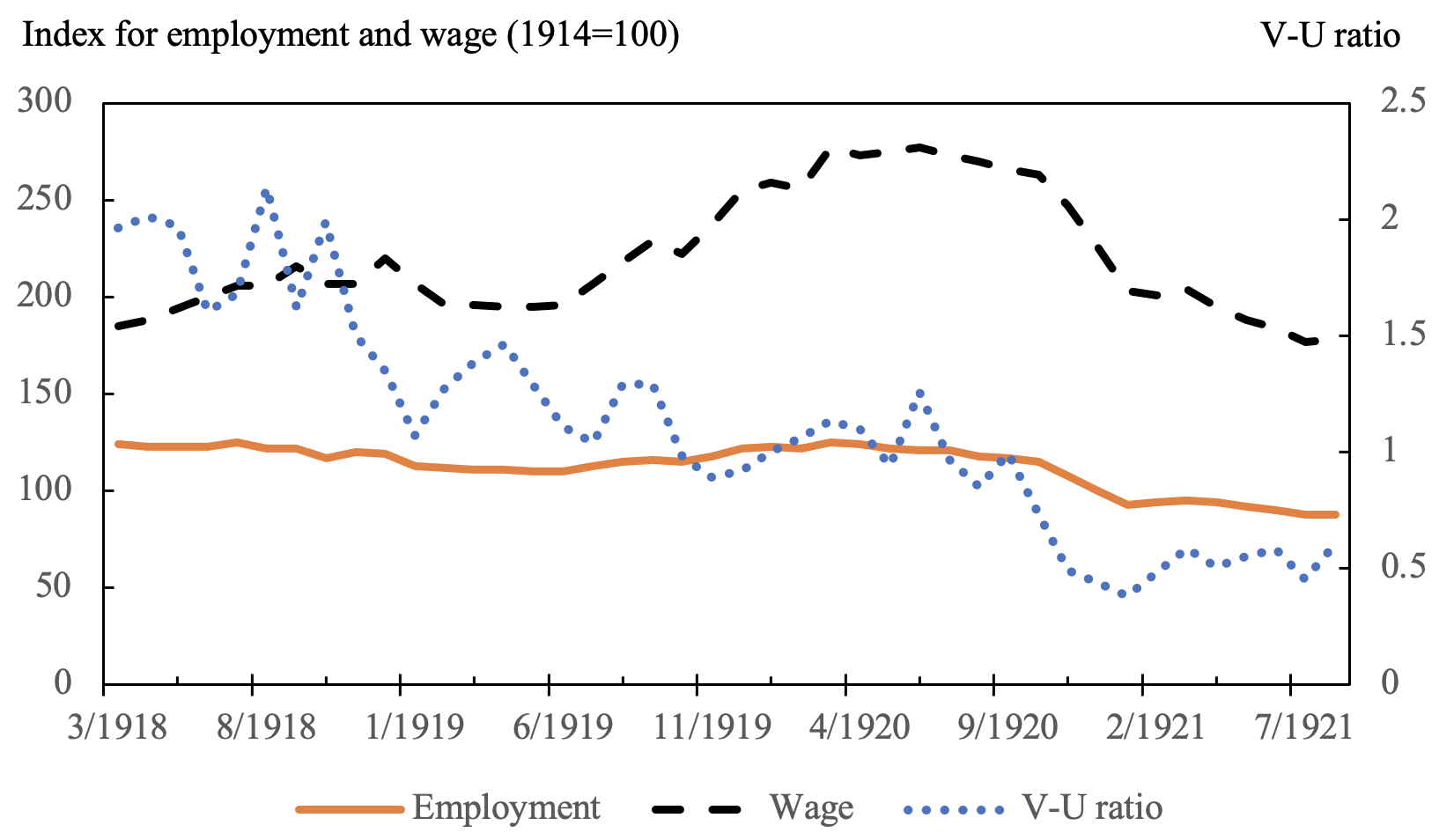

Because the manufacturing sector played an important role during this period, we examine the labour market dynamics for the manufacturing sector more closely. In Figure 4, we plot labour market tightness, employment, and wages for the manufacturing sector between the March of 1918 and the August of 1921. Labour market tightness is associated with high rates of employment. Both labour market tightness and employment fell after WWI but remained stable until 1920. They fell sharply after mid-1920. Wages grew much faster than employment after WWI. Much like employment, wages fell sharply after mid-1920.

Figure 4 Labour market tightness, employment, and wage, manufacturing sector, 1918:M3-1921:M8

Source: Labor Market Bulletin.

Lastly, we show the uneven effect of the recession on labour markets by gender.

We compare whether labour market tightness for male workers and female workers differed. We find that there were differences in labour supply, labour demand, and new hires across gender. For male workers, most labour demand came from industrial sectors during the war and industrial and agricultural sectors after the war. For female workers, most labour demand came from industrial sectors during the war and from service sectors after the war. Labour demand for the manufacturing sector contracted sharply while labour demand for the service sector contracted mildly during the severe recession of 1920–21. As a result, job losses were greater for men than women.

Policy implications

Policymakers are concerned about inflation, which has risen to the highest level in the past 40 years in the US, amid the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, the Federal Reserve has begun raising interest rates to curb inflation and has started to scale back on quantitative easing. The labour market, which is a lagging indicator for the economy, is also showing signs that hiring momentum is slipping. Initial jobless claims have risen since the second quarter, and the four-week moving average reached its highest level since January. Moreover, strong (tight) labour markets can become weak (slack) faster than policymakers may anticipate (Blanchflower et al. 2022). Indeed, our results demonstrate that labour demand reacted sharply and quickly to the tightening of monetary policy at a speed that can outpace policymakers’ abilities to track current economic conditions.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve System, or the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

References

Anderson, H and J-Wook C (2022), "Labor Market Tightness during WWI and the Postwar Recession of 1920-1921," Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-049.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2022), Monetary Policy Report.

Blanchflower, D, A Bryson, and J Spurling (2022),“Labour Markets are not as Tight as You Think,” VoxEU.org, 13 October.

Huizinga, J and F S Mishkin (1986). “Monetary Policy Regime Shifts and the Unusual Behavior of Real Interest Rates,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, Vol. 24, pp. 231–274.

Powell, J H (2022), “Restoring Price Stability,” speech delivered at the conference “Policy Options for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth,” Washington, DC. 21-22 March.

Rockoff, H (2004), “Until it’s Over, Over There: The US Economy in World War I”, NBER Working Paper No. 10580.

Romer, C D (1988), “World War I and the Postwar Depression: A Reinterpretation Based on Alternative Estimates of GNP”, Journal of Monetary Economics 22(1): 91–115.

Summers, L (2022), “How Tight are US Labor Markets?”, VoxEU.org, 16 March.