Institutions are widely viewed as a fundamental cause of economic performance. But what are the causes of institutions? We don’t have a definitive answer (Acemoglu et al. 2005, Ogilvie 2007, Ogilvie and Carus 2014). But since institutions often have roots far in the past, looking at historical institutions provides a way to tackle the question.

Labour-coercion institutions – serfdom and slavery – have profoundly affected many economies through the centuries. Serfdom obliged rural people to do forced labour for landlords, who also regulated their mobility, demographic behaviour, and market participation. Serfdom prevailed in most European economies from roughly 800 AD onwards, weakening between 1300 and 1500 in the west of the continent but surviving and intensifying in most of the centre and east. This development is known as the ‘second serfdom’ (Klein 2014, Ogilvie 2014a). In many serf economies, a large percentage of rural families had to perform forced labour. Since the rural economy produced 80-90% of pre-industrial GDP, serfdom affected the majority of economic activity. Labour coercion under serfdom reduced labour productivity, human capital investment, innovation, and living standards, so much so that its varying intensity is widely regarded as a major determinant of divergent European economic performance between 1350 and 1864 (Broadberry and Gupta 2006, Dennison 2011, Ogilvie and Carus 2014, Klein 2014, Ogilvie 2014b, Baten et al. 2014, Markevich and Zhuravskaya 2017).

Theories of serfdom

What caused serfdom to be stronger in some places and weaker in others? One famous theory was put forward by Domar (1970), who hypothesised that serfdom was a response to factor endowments – specifically, high land-labour ratios. In economies where wages were high because labour was scarce relative to land, Domar argued, landowners devised institutions such as serfdom to ensure they could get labour to work their land at a lower cost than would be the case in a non-coerced labour market.

This hypothesis seems to fall foul of the facts. Postan (1937, 1966) and North and Thomas (1973) argued that, on the contrary, rising land-labour ratios after the Black Death in 1350 made serfdom decline by increasing outside options for peasants in vacant rural holdings and urban workshops. Brenner (1976) rejected all claims that factor proportions affected serfdom, pointing out that rises in the land-labour ratio after 1350 coincided with the decline of serfdom in Western Europe and its intensification in the east. Subsequent scholarship argued that country-specific variables such as class struggle, state power, and the overall institutional framework were decisive – although a different story was told for each society (Aston and Philpin 1988, Hatcher and Bailey 2001).

Acemoglu and Wolitzky (2011) breathed new life into Domar’s idea by providing a theoretical framework explaining why factor endowments might affect labour coercion differently in different contexts. A rise in the land-labour ratio, they argued, could have two countervailing effects. It might increase the price of the output produced by the landlord, which would increase the productivity of labour coercion, and thus increase the quantity of coercion, along the lines hypothesised by Domar. But greater labour scarcity might also increase the wage that serfs could earn in outside activities, for instance in the urban sector, which would decrease the productivity of labour coercion, and thus decrease the quantity of coercion, as argued by Postan and North. The relative size of these two effects will vary with market demand for landlords’ goods and wages for serfs outside the coerced sector. So the same rise in land-labour ratios can result in different coercion outcomes in different societies.

What happened in Bohemia?

This new framework is clear and powerful, but needs to be investigated empirically. To do this, we collected extraordinarily detailed micro-level data on 11,670 serf villages, covering the entirety of 18th century Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic (Klein and Ogilvie 2017). We calculate how much coerced labour serfs had to do, both human-only and in human-animal teams. We then measure the economic fundamentals faced by serfs and lords – land-labour ratios for different types of land, village sizes, outside options in different categories of town, geographical location, types of lord, fragmentation of lordship, and many other variables.

We use a multiple regression framework that controls for other influences on labour coercion, enabling us to identify the effect of factor proportions in a way that qualitative studies could not. By analysing a specific society, we also control for political-economy variables – class struggle, state power, the overall institutional framework – which may have obscured the impact of factor proportions in previous studies.

Unearthing the Domar effect

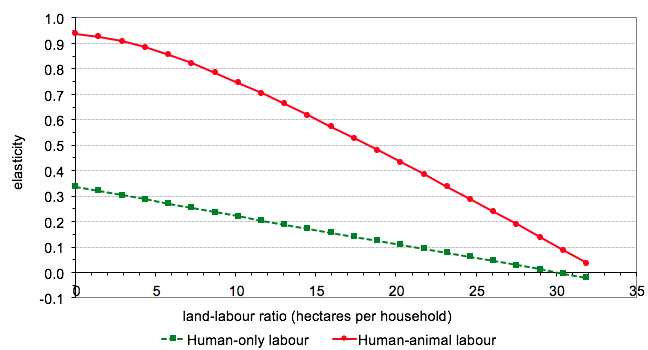

We find that where the land-labour ratio was higher, labour coercion was significantly higher, and thus that the Domar effect outweighed any countervailing outside options effect. Figure 1 graphs the elasticity of labour coercion with respect to the land-labour ratio according to our regression models, setting all other regressors at their sample mean values.

Figure 1 Elasticity of coerced labour in Bohemia with respect to the land-labour ratio, 1757 (two-part regressions)

For human-only coerced labour, the elasticity with respect to the land-labour ratio is non-trivial, lying in the 0.20-0.34 range, for the three-quarters of villages where the land-labour ratio is below 12 hectares per household. For human-animal coerced labour, the elasticities are three times as big. They lie between 0.5 and 1.0 for the 92% of villages where the land-labour ratio is below 17 hectares per household and are still non-trivial, lying in the 0.2-0.5 range, for the remaining villages.

Why did the land-labour ratio affect human-animal more than human-only coerced labour? We think the Domar effect was bigger for human-animal labour and that the outside options effect was smaller. The Domar effect was intensified by complementarities between human and animal labour, and the usefulness of animals in transporting grain to manorial breweries, wood to manorial glassworks, and ore to manorial ironworks (Klein 2014). The outside options effect was reduced by lack of demand for animal labour in alternative uses, such as urban crafts and commerce, which required human dexterity, communication, and calculation more than brute force. Animals were also harder to hide than humans, so landlords could detect their illicit use more readily, further reducing outside options for human-animal labour teams.

Why did labour coercion respond less to the land-labour ratio as the latter increased? It happened, we think, because of technical constraints on coercion. In villages with very high land-labour ratios, serfs needed most of their labour just to keep themselves alive. Lords could not extract it without killing the serfs. When labour became extremely scarce, that is, market pressures broke through and no coercion technology could resist them. Bohemian landlords recognised these constraints themselves, granting temporary freedom from coerced labour in drastically depopulated villages after the Thirty Years War (Cerman 1996, Štefanová 1999, Zeitlhofer 2014).

Feeble outside options

How did outside options in the urban sector affect labour coercion? A striking result from our regressions is that the urban potential available to a serf village – the size and proximity of urban markets – had almost no statistically or economically significant effect on labour coercion in the village. The only urban effects that were statistically (and in one case economically) significant were positive – that is, they increased labour coercion – suggesting towns created greater opportunities for lords than serfs. This is not surprising, since historical evidence shows Bohemian towns doing things that stifled rather than increased serfs’ outside options, specifically by restricting rural crafts and trades that competed with those practised by town citizens (Cerman 1996, Ogilvie 2001, Klein and Ogilvie 2016). But most urban effects on labour coercion were so small as to have no economic significance.

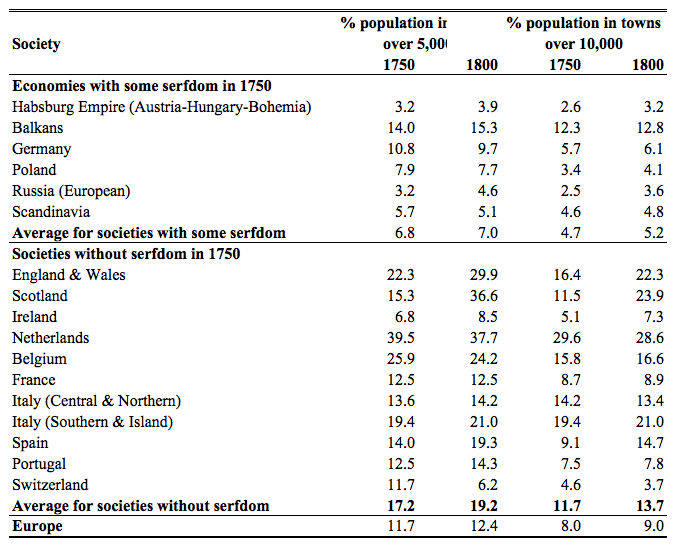

This is consistent with the weakness of towns in Bohemia, as in most parts of eastern-central Europe. As Table 1 shows, in European societies where serfdom still survived in 1750, just 7% of the population lived in towns over 5,000 inhabitants, compared to 17-19% in societies without serfdom. In the Habsburg Empire, which included Bohemia, just 3-4% of people lived in towns over 5,000 inhabitants. In serf societies, towns were too few and weak to increase wages for serfs or prices for landlords. They provided no serious outside options for either party, so they exercised no serious effect on serfdom.

Table 1 Urbanization in European Societies, 1750 and 1800

Note: Average for societies with and without serfdom in 1750 is calculated on the basis of total population.

Source: Calculated from Malanima (2010), pp. 260-2.

Factor endowments shape institutions

Our study holds constant political-economy variables by analysing a specific society, and controls for other influences on serfdom. This enables us to provide, for the first time, clear evidence that the net effect of higher land-labour ratios was indeed to increase labour coercion. The positive impact intensified when landlords extracted labour in human-animal teams, and diminished as land-labour ratios rose; both patterns consistent with technical limits on coercion. Towns in Bohemia, and in most European societies where serfdom survived in the 18th century, were usually too feeble to provide outside options to either serfs or landlords, and thus did not alleviate coercion – if anything, they sometimes slightly intensified it. So Domar was right – factor endowments can significantly influence serfdom. Institutions, our study shows, are partly shaped by economic fundamentals.

References

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson and J. A. Robinson (2005). “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth.” In P. Aghion and S. N. Durlauf, eds., Handbook of Economic Growth. Amsterdam / London, Elsevier. 1A: 385-472.

Acemoglu, D. and A. Wolitzky (2011). “The Economics of Labor Coercion.” Econometrica 79(2): 555-600.

Aston, T. H. and C. H. E. Philpin, eds. (1988). The Brenner Debate. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Baten, J., M. Szołtysek and M. Campestrini (2017). “ ‘Girl Power’ in Eastern Europe? The Human Capital Development of Central-Eastern and Eastern Europe in the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries and its Determinants.” European Review of Economic History 21(1): 29-63.

Brenner, R. (1976). “Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial England.” Past & Present 70: 30-75.

Broadberry, S. and B. Gupta (2006). “The Early Modern Great Divergence: Wages, Prices and Economic Development in Europe and Asia, 1500–1800.” Economic History Review 59(1): 2-31.

Cerman, M. (1996). “Proto-industrialisierung und Grundherrschaft. Ländliche Sozialstruktur, Feudalismus und Proto-industrielles Heimgewerbe in Nordböhmen vom 14. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert (1381-1790)”. Ph.D. dissertation, Vienna.

Dennison, T. (2011). The Institutional Framework of Russian Serfdom. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Domar, E. D. (1970). “The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: a Hypothesis.” Journal of Economic History 30(1): 18-32.

Hatcher, J. and M. Bailey (2001). Modelling the Middle Ages: the History and Theory of England’s Economic Development. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Klein, A. (2014). “The Institutions of the 'Second Serfdom' and Economic Efficiency: Review of the Existing Evidence for Bohemia.” In S. Cavaciocchi, ed., Slavery and Serfdom in the European Economy from the 11th to the 18th Centuries. Florence, Firenze University Press: 59-82.

Klein, A. and S. Ogilvie (2016). “Occupational Structure in the Czech Lands under the Second Serfdom.” Economic History Review 69(2): 493-521.

Klein, A. and S. Ogilvie (2017). “Was Domar Right? Serfdom and Factor Endowments in Bohemia.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12388.

Malanima, P. (2010). “Urbanization.” In S. Broadberry and K. H. O’Rourke, eds., The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe, Vol 1: 1700-1870. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 1: 235-263.

Markevich, A. and E. Zhuravskaya (2018 forthcoming). “The Economic Effects of the Abolition of Serfdom: Evidence from the Russian Empire.” American Economic Review.

North, D. C. and R. P. Thomas (1973). The Rise of the Western World. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Ogilvie, S. (2001). “The Economic World of the Bohemian Serf: Economic Concepts, Preferences and Constraints on the Estate of Friedland, 1583-1692.” Economic History Review 54(3): 430-453.

Ogilvie, S. (2007). “ ‘Whatever Is, Is Right’? Economic Institutions in Pre-Industrial Europe.” Economic History Review 60(4): 649-684.

Ogilvie, S. (2014a). “Serfdom and the Institutional System in Early Modern Germany.” In S. Cavaciocchi, ed., Slavery and Serfdom in the European Economy from the 11th to the 18th Centuries. Florence, Firenze University Press: 33-58.

Ogilvie, S. (2014b). “Slavery and Serfdom in the European Economy: Contribution to Tavola Rotunda.” In S. Cavaciocchi, ed., Slavery and Serfdom in the European Economy from the 11th to the 18th Centuries. Florence, Firenze University Press: 689-693.

Ogilvie, S. and A. W. Carus (2014). “Institutions and Economic Growth in Historical Perspective.” In S. Durlauf and P. Aghion, eds., Handbook of Economic Growth. Amsterdam, Elsevier. 2A: 405-514.

Postan, M. M. (1937). “The Chronology of Labour Services.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 20: 169-193.

Postan, M. M. (1966). “Medieval Agrarian Society in its Prime: England.” In M. M. Postan, ed., The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, Volume 1: The Agrarian Life of the Middle Ages. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 548-632.

Štefanová, D. (1999). Erbschaftspraxis und Handlungsspielräume der Untertanen in einer gutsherrschaftlichen Gesellschaft. Die Herrschaft Frýdlant in Nordböhmen, 1558-1750. Munich, Oldenbourg.

Zeitlhofer, H. (2014). Besitzwechsel und sozialer Wandel. Lebensläufe und sozioökonomische Entwicklungen im südlichen Böhmerwald, 1640-1840. Wien, Böhlau Wien.