Longstanding arguments that ill health impedes economic development hit a snag when evidence emerged that the global decline of infectious disease in the mid-20th century did not bring prosperity to the world’s unhealthiest countries (Acemoglu and Johnson 2007).

Health, population and the macroeconomy

Morbidity rates fell, but so too did mortality rates – especially among children – which increased population growth and thus undercut per capita economic progress. This historical episode, commonly called the ‘global epidemiologic transition’, highlights the delicate interplay of health, population, and the macroeconomy. For those interested in forecasting the economic effects of future health improvements in poor countries, two important questions emerge.

- First, what is the broader impact of reducing morbidity among the living?

This issue is sure to become more important as countries tackle child mortality but fail to eliminate sickness and hunger among the legions of survivors.

- Second, how might the economic effects of health improvements differ in the long- and short-term?

If positive effects occur at a lag, then existing research may understate the macroeconomic benefits of improving population health.

Early-life health

The answers to both these questions depend on how the effects of early-life health play out over the lifecycle. A large body of research on the US and Europe suggests that poor health in utero and in childhood reduces educational attainment, earnings potential, cognitive skill, and health in adulthood (Currie 2009). If similar dynamics are evident in poor countries, then the aggregate economic benefits of health programs in these settings will take a generation or more to fully emerge. These benefits may also become more pronounced as a growing fraction of sick children in poor countries survive to adulthood (Knoll Rajaratnam et al. 2010).

In fact, the cumulative effects of negative health events in childhood are likely to be larger in developing countries, for three reasons. First, these events take place more often, putting each child at greater risk of experiencing multiple episodes of ill health. Second, these multiple health events are likely to interact; for example, diarrheal disease exacerbates malnutrition by impeding the body’s absorption of already-limited nutrients. Third, health systems in poor countries are generally better at managing acute health events than their chronic after-effects. Poor parents may be similarly ill-equipped to compensate for these after-effects. These deficiencies are usually graver in poor countries than in rich. A given health episode will therefore have more intense long-term effects in a poor country.

Metrics

Due in part to a recent expansion in data availability and study opportunities, a burgeoning literature examines the long-term effects of early-life health in developing countries. Results based on varied study designs suggest that episodes of poor health in early life do have lasting negative consequences in a broad swath of settings. The literature is split in roughly two parts. The first uses the size and shape of the human body to broadly proxy for the experience of early-life adversity, while the second measures specific forms of that adversity and seeks to estimate their effects. Both forms of evidence suggest that policy-makers interested in reducing inequalities and deficits in adult outcomes should give ample attention to the early years of life.

The benefits of body size

Genes, the environment, and their interaction determine the size and shape of the human body. Although a great deal of variation in body size is genetic, the environment, broadly construed, nonetheless plays an important role1. On average, taller adults and bigger babies have experienced more optimal conditions during periods of physical growth. As a result, birth weight and height provide noisy but useful measures of health and nutrition in utero and in early life, respectively. The inputs that most encourage physical growth during gestation, infancy, and childhood also promote cognitive development and, more generally, health.

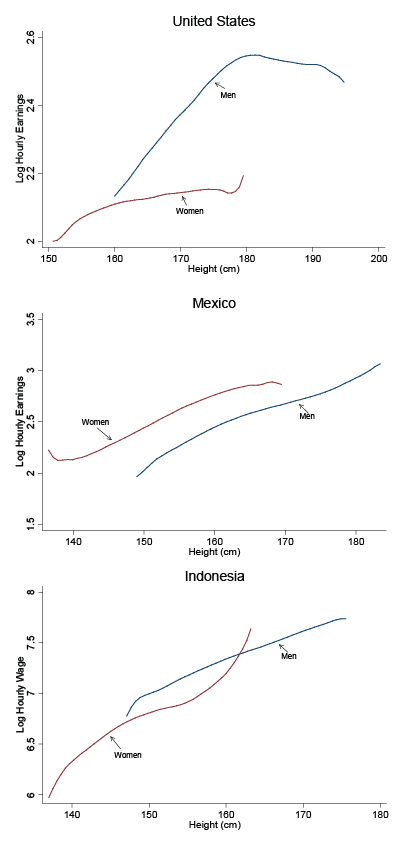

Figure 1. Height and earnings in the US, Mexico, and Indonesia

Notes: Local linear regressions based on the 1988-1997 US PSID (earnings measured in constant 1990 dollars), the 2002 Mexico Family Life Survey (earnings measured in 2002 pesos), and the 2002 Indonesia Family Life Survey (wages measured in 2000 rupiah).

Taller and smarter?

Indeed, adults with greater heights or birth weights obtain more education, perform better on cognitive tests, work in higher-skill occupations, earn more, and enjoy better health than their smaller counterparts. These patterns are well-documented in rich countries for both outcomes (Steckel 2008, Currie 2009), but developing-country evidence has primarily focused on height, perhaps because few studies in these settings have followed individuals from birth into adulthood. The earnings boost per inch of height in poor countries far exceeds that in rich countries (e.g. Strauss and Thomas 1998, Case and Paxson 2009, Vogl 2012), perhaps because the greater variability of childhood health conditions in poor countries makes height less noisy as a proxy for these conditions. See Figure 1 for example, and note the compressed y-axis scale of the panel that uses US data. One interesting similarity between the two settings relates to occupational choice. In settings both rich and poor, taller workers are more likely to hold white-collar jobs and less likely engage in manual labour (Case and Paxson 2009, Vogl 2012). This finding suggests – somewhat surprisingly – that the return to height in poor countries may have more to do with cognitive skill than with physical strength.

What happens when the health environment changes?

The evidence on body size has an important drawback; we cannot observe the events that cause shortfalls in height and birth weight. A growing literature studies the long-term effects of specific shocks to early-life health in developing countries – including moderate malnutrition, famine, infectious disease, and war2.On moderate malnutrition, Maccini and Yang (2009) document that Indonesian women fare better economically and educationally if they experienced greater local rainfall in early life. Given agriculture’s large role in the Indonesian economy, they hypothesise that greater rainfall increases family income and therefore access to good nutrition3.

Results on the effects of famine are less clear-cut; famines kill many and kill selectively, implying that survivors are not generally comparable to pre-famine populations.

On infectious disease, the literature shows more consistent evidence of negative long-term effects. Bleakley (2010), Cutler et al. (2010), and Lucas (2010) have studied malaria eradication campaigns in the Americas and South Asia. In all of seven countries under study, a comparison of adults born before and after eradication shows larger socioeconomic gains in areas of the countries that were previously more malarious. This result suggests that malaria exposure in childhood has a negative effect on adult socioeconomic outcomes or, equivalently, that eradication benefited children in the long run.

Improvements in health without higher per capita income?

This long-term benefit is surprising in light of Acemoglu and Johnson’s (2007) finding that the global epidemiologic transition – of which malaria eradication was a part – did not raise per capita income. But one can easily reconcile these results (cf. Bleakley 2009, Ashraf et al. 2009). First, because researchers compare individuals within countries, the microeconomic studies of long-term effects on children may miss the consequences of population growth. Second, the seven countries analysed in these microeconomic studies suffered primarily from vivax malaria – a debilitating but not usually fatal variant of the disease – so the mortality effects of eradication may have been less pronounced than in other parts of the global epidemiologic transition. Third, Acemoglu and Johnson’s study window may have been too short to fully detect the long-term benefits of the transition.

Conclusions

As child mortality rates continue their global decline, the long-term consequences of early-life disease and hunger will grow in importance. Many aspects of these long-term dynamics remain poorly understood. Two particularly glaring omissions not included in the developing-country literature are pollution and HIV/AIDS. Both are of paramount importance in many developing countries today. Nonetheless, the existing evidence suggests that health conditions in childhood lay important roots for outcomes experienced over the lifecycle.

References

Acemoglu, D, and S Johnson (2007) “Disease and Development: The Effect of Life Expectancy on Economic Growth”, Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 925-985.

Ashraf, Q H, A Lester, and D. N. Weil (2008), “When Does Improving Health Raise GDP?”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 23(1), 157-204.

Bleakley, H (2009), “Comment on ‘When Does Improving Health Raise GDP?’” In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2008, 23, 205-220, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Bleakley, H (2010), “Malaria Eradication in the Americas: A Retrospective Analysis of Childhood Exposure”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 1-45.

Case, A, & C Paxson (2008), “Stature and Status: Height, Ability, and Labor Market Outcomes”, Journal of Political Economy, 116(3), 499-532.

Currie, J (2009), “Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Socioeconomic Status, Poor Health in Childhood, and Human Capital Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 87-122.

Currie, J, & T Vogl (2012). “Early-Life Health and Adult Circumstance in Developing Countries”, NBER Working Paper, 18371.

Cutler, D, W Fung, M Kremer, M Singhal, & T Vogl (2010), “Early-Life Malaria Exposure and Adult Outcomes: Evidence from Malaria Eradication in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 72-94.

Lucas, A M (2010), “Malaria Eradication and Educational Attainment: Evidence from Paraguay and Sri Lanka”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 46-71.

Maccini, S, and D Yang (2009), “Under the Weather: Health, Schooling, and Economic Consequences of Early-Life Rainfall”, American Economic Review, 99(3), 1006-1026.

Rajaratnam, J K, J R Marcus, A D Flaxman, H Wang, A Levin-Rector, L. Dwyer, M. Costa, A. Lopez, and C.J. Murray (2010), “Neonatal, Postneonatal, Childhood, and Under-5 Mortality for 187 Countries, 1970–2010: A Systematic Analysis of Progress Towards Millennium Development Goal 4,” The Lancet, 375(9730), 1988-2008.

Steckel, R H (2008), “Biological Measures of the Standard of Living”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 129-152.

Vogl, T (2012), “Height, Skills, and Labor Market Outcomes in Mexico”, NBER Working Paper, 18318.

1 Environmental factors account for some 20% of adult height variation in the US and Europe; in poorer countries, the share is higher (Silventoinen 2003).

2 Here we list just a few interesting examples; see our review paper (Currie and Vogl 2012) for a more complete list

3 Somewhat surprisingly, Maccini and Yang do not find significant effects on male outcomes.