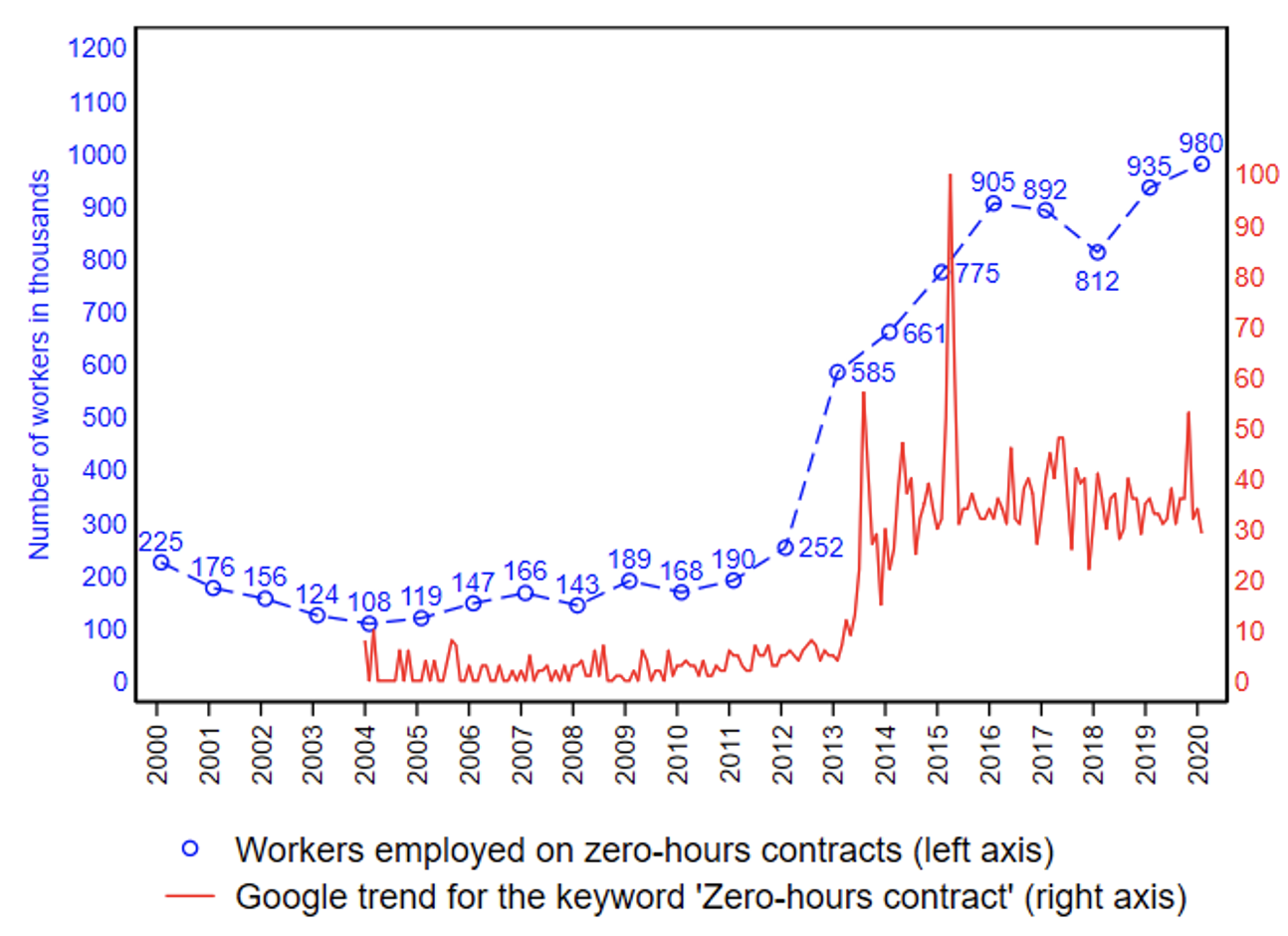

Less Than Zero was the debut novel of Bret Easton Ellis in 1985, whose title was borrowed from a famous Elvis Costello song. ‘Zero’ is also a short name for zero-hours contracts (ZHCs), which have spread in the UK after the Great Recession, particularly in the low-pay segment of the labour market. These gig-economy contracts exempt employers from the requirement to provide any minimum working hours while allowing workers to decline any workload. They have become the focus of a heated controversy in the UK media and political arena (Adams et al. 2018), having reached almost one million workers (i.e. about 3% of the UK labour force) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Workers on ZHCs and Google Trend for “zero-hours contracts”

Data source: UK labour force surveys.

On the one hand, employers, and some workers point to the benefits of having flexible labour contracts under fluctuating demand conditions. On the other hand, trade unions and other commentators have raised fierce concerns about the potential exploitation of workers, especially those employed through online platforms (Dube et al. 2020). Are ZHCs ‘less or more than zero’ in terms of welfare? This controversy has implications for the regulation of employment relations. Indeed, the legal status of individuals on ZHCs is that of “worker”, which lies between the categories of “employee” and “self-employed”, making it sometimes unclear what benefits and welfare programmes they should be entitled to (Benghalem et al. 2021). Similar debates exist in other OECD countries, where on-call contracts have been put into focus by the emergence of the platform-based economy (Angrist et al. 2017, Narita et al. 2021).

Despite this ongoing debate, research on the equilibrium and welfare effects of on-call contracts is only at an early stage, partly due to the fact that detailed data on these labour contracts have only recently become available (Abraham et al. 2021).

A structural model of zero-hours contracts

To make up for the lack of direct data, one approach consists in gathering evidence about the effects of these contracts through specific questionnaire surveys (Katz and Krueger 2019, Boeri et al. 2020) or field experiments (Mas and Pallais 2017). Another approach relies on combining a structural model with the empirical information provided by labour force survey (LFS) data. This is the approach we undertake in a recent paper (Dolado et al. 2021), in which we seek to understand the pros and cons of ZHCs based on a frictional labour-market model where firms and workers are both heterogeneous in their valuation of ZHCs relative to regular contracts (typically part-time and temporary jobs with fixed hours). Firms are characterised by more or less volatility in their orders, capturing the fluctuating demand conditions that affect the low-pay service sectors where ZHCs are commonly used. Given their other time commitments, workers differ from each other with respect to the utility they derive from working short hours, and since the latter are more prevalent in ZHCs, this creates a preference for or against these contracts. Thus, trade-offs between contract types arise for different agents, leading to sorting patterns of workers across firms that choose to offer either ZHCs or regular contracts.

In particular, our model emphasises three channels through which ZHCs affect labour market outcomes:

- a job creation effect, as firms endowed with more volatile business conditions can only enter the market posting vacancies under these flexible contracts;

- a substitution effect, whereby some jobs that would be otherwise viable under regular contracts become advertised as ZHCs; and

- a participation effect, as workers who prefer flexible work schedules only join the labour market when ZHCs are available.

The relative importance of each of these three channels in shaping the equilibrium and welfare effects of ZHCs is ultimately a quantitative issue. We address it by calibrating our model to data and policies from the UK, using eight waves (September 2018 to March 2020) of its labour force survey distinguishing among individuals in nonemployment, on regular contracts, and ZHCs. In particular, we focus on the low-pay segment of the UK labour market, where workers get paid around the minimum wage, and which accounts for about 7% of overall salaried employment, with a nonemployment rate close to 10%. We document the following features:

- About 4.6% of workers in this segment hold a ZHC (i.e. 1.5 times the share of workers on ZHCs in the overall UK labour market).

- ZHCs are more prevalent at both ends of the working life (e.g. among students and semi-retirees).

- The distribution of workers on regular contracts and on ZHCs by education is fairly similar.

- ‘Accommodation and food services’, ‘Health and social work’ and ‘Arts, entertainment and recreation” are the industries in which ZHC jobs are over-represented.

- The distribution by gender of ZHC and regular contract workers (56% and 60% of women, respectively) is not significantly different.

- Mean weekly working hours are shorter in ZHC jobs than in regular contract jobs (19.4 versus 28.1) and exhibit higher volatility.

Another key source of information for our model is the transition matrix between three labour market states under consideration. This matrix shows that the transition rate to nonemployment is almost 50% larger in ZHC contracts than in regular contracts, and that job-to-job transitions involving a change of contract type are predominantly from ZHC to regular contracts.

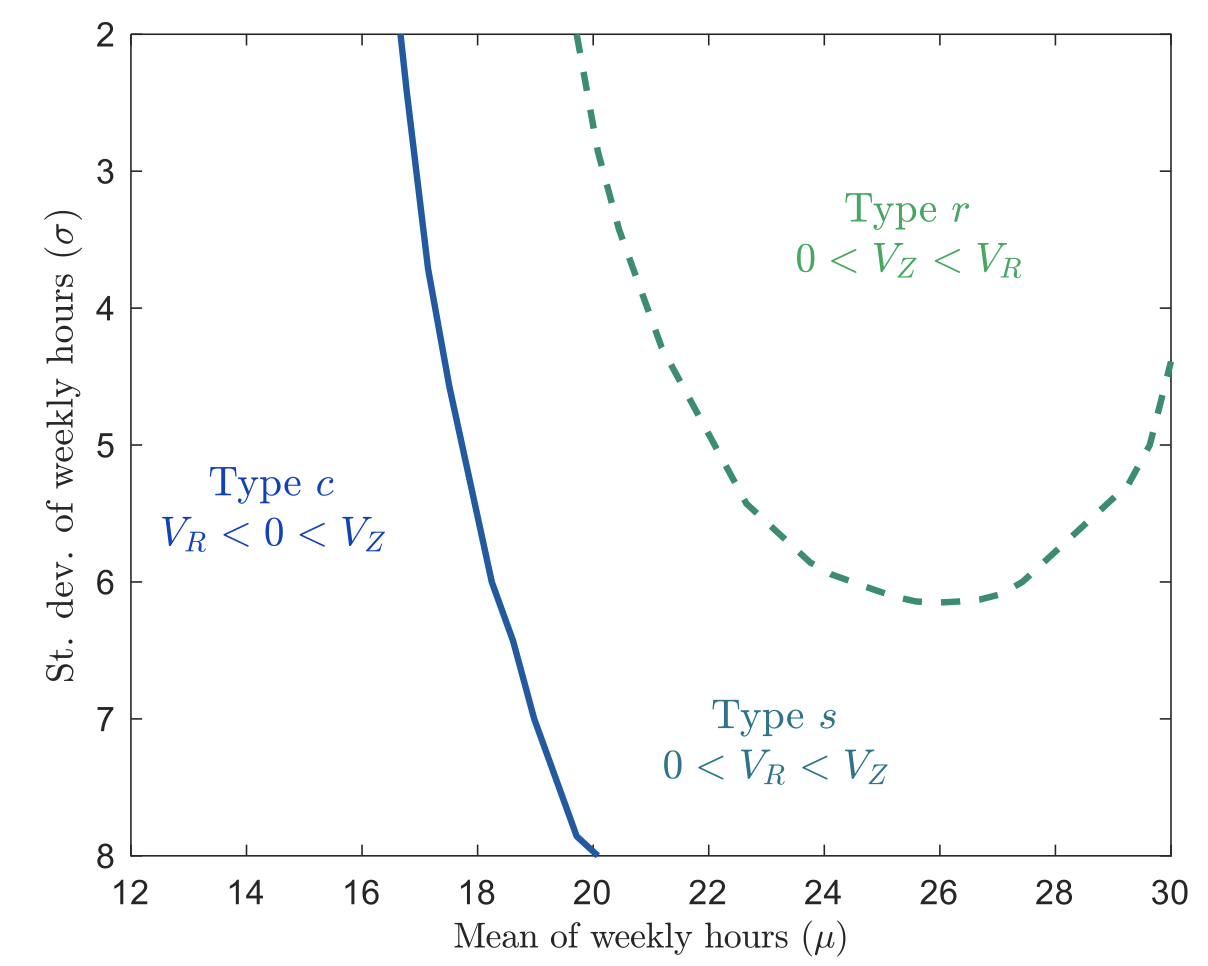

Figure 2 shows how firms in our model rank the different contract types, depending on the mean and dispersion of working hours that would exactly meet the demand that a firm faces at a given point in time. In the top-right corner, firms that face higher and less volatile demand are called type-r firms: posting regular contracts (whose asset value is VR) is their preferred option, regardless of whether ZHCs exist (VZ) or not. When demand is either lower on average or more dispersed, firms are of type s: they substitute ZHCs for regular contracts. Finally, firms that face even lower average or more dispersed demand are those of type c, in that they need the flexibility afforded by ZHCs to create jobs.

Figure 2 Firm type as a function of the mean and dispersion of working hours required to meet consumer demand

On the other side of the market, there is heterogeneity with respect to workers’ preference for short hours. Some workers always rank employment over non-employment, and conditional on working they prefer a regular employment contract over a ZHC. We call these highly attached workers, as their preferences are such that R ≻ Z ≻ N. These workers do not value short hours very much: we find that they would be willing to give up at most £4.70 of consumption (per week) to avoid working one hour beyond their work availability. On the other hand, the least attached workers (for whom Z ≻ N ≻ R, like students or elderly people who cannot commit to a fixed-hours job) have a much higher valuation of short hours. They would give up at least £10.90 of consumption to avoid working one hour beyond their work availability. This marginal willingness to pay is 45% higher than the hourly minimum wage (£7.5 per hour) that workers can earn in this segment of the labour market.

Policy experiments and recommendations

Motivated by the UK debates on the consequences of the spread of ZHCs, we then use our model to analyse the impact of a potential ban on such contracts and the impact on these flexible contracts of a rise in the minimum wage. Our main quantitative findings are as follows.

- A ban on ZHCs leads to an increase of the unemployment rate in the low-pay labour market of between 2 and 2.7 percentage points. At the same time, it makes the employment rate of this segment drop by between 6.8 and 7.4 percentage points. These larger impacts on the employment rate comes from the lower labour force participation of less-attached workers in the absence of ZHCs.

- Depending both on workers’ valuation of short hours and on the strength of the substitution effects (i.e. the mix between firms that can substitute ZHCs with regular contracts and those that cannot create jobs without ZHCs), the welfare impact of banning ZHCs ranges between -0.7% and -1.6% of foregone consumption. Yet our model delivers mixed welfare effects of ZHCs. In effect, highly attached workers would experience a gain in consumption of between 0.2% and 0.5% were ZHCs to be replaced by regular contracts. This finding rationalises concerns about workers suffering the costs of unpredictable hours schedules under ZHCs, but is mitigated by the other forces (labour force participation and job creation) that come into play to appreciate the effects of ZHCs in a general equilibrium setting.

- Lastly, our model is able to rationalise recent results by Datta et al. (2019) about how a rise in the UK National Living Wage in 2016 led to a higher share of ZHCs in the low-wage social care sector. In view of the higher labour costs, firms with profitable regular contracts before the rise switched to ZHC contracts to lower these costs, while those which were offering ZHC contracts to start with would expand in parallel with a reduction in the share of those firms that could only offer regular contracts.

In our analysis, we have assumed that the firm chooses the workload in terms of hours and the worker chooses the timing of work. We found important differences when we made different assumptions along this dimension of the model. Anecdotal evidence suggests that any combination of choices of hours and timing made by the worker or the firm exist within ZHCs and are often not clearly defined. Given the costs incurred on both sides when the match is producing fewer/more hours than desired, a promising avenue for improving workers’ welfare would be to clarify the extent and sharing of flexibility of all employment relationships.

In light of these findings, we see three policy recommendations that should be brought into the debate regarding the availability of ZHCs:

- ZHCs could be restricted to job matches where workers opt for a ZHC when offered a choice of contract.

- Access to ZHCs could be prioritised for workers employed in small firms rather than in large firms. A larger workforce makes it easier to smooth out the volatility of business conditions, and as a result it is likely that substitution is a bigger driver of the use of ZHCs in large firms, whereas in small firms the job creation channel of ZHCs might be relatively more important.

- The way flexibility over hours is shared between workers and firms could be regulated. A first step in that direction is to recognise that employment contracts are often incomplete with regards to the sharing of hours flexibility.

References

Abraham, K, J C Haltiwanger, K Sandusky and J R Spletzer (2021), “Measuring the gig economy: Current knowledge and open issues”, in C A Corrado, J Haskel, J Miranda and and D E Sichel (eds), Measuring and Accounting for Innovation in the 21st Century, NBER.

Angrist, J, S Caldwell and J Hall (2017), “Uber versus taxi: A driver’s eye view”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Adams, A, J Freedman and J Prassl (2018), “Rethinking legal taxonomies for the gig economy”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 34(3): 475–494.

Benghalem, H, P Cahuc and P Villedieu (2021), “The lock-in effects of part-time unemployment benefits”, VoxEU.org, 5 April.

Boeri, T, G Giupponi, A B Krueger and S Machin (2020), “Solo self-employment and alternative work arrangements: A cross-country perspective on the changing composition of jobs”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(1): 170–195.

Datta, N, S Giupponi and S Machin (2019), “Zero-hours contracts and labour market policy”, Economic Policy 34(99): 369–427.

Dolado, J, E Lalé and H Turon (2021), “Zero-hours contracts in a frictional labour market”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16843.

Dube, A, J Jacobs, J Naidu and S Suri (2020), “Monopsony in online labor markets”, American Economic Review: Insights 2(1): 33–46.

Katz, L F and A B Krueger (2019), “The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995-2015”, Industrial & Labor Relations Review 72(2): 382–416.

Mas, A and A Pallais (2017), “Valuing alternative work arrangements”, American Economic Review 107(12): 3722–59.

Narita, Y, S Aihara, M Matsutani and Y Saito (2021), “Machine learning as a natural experiment: Application to fashion e-commerce”, VoxEU.org, 28 April.