Editors’ note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war. It first appeared as an article on the Economics Observatory.

More than three million people have now fled Ukraine as a result of Russia’s invasion, according to the UN.1 This massive refugee flow resulting from Putin’s unprovoked attack on Ukraine requires a policy response from all European countries, including the UK.

The UK was at the forefront of helping those fleeing from Nazi Germany. It also has a moral obligation to help those fleeing the atrocities of Putin’s army today. Some countries – for example, Poland, Moldova, and Romania – have given amazing welcomes to Ukrainians. It is estimated that over 1.7 million Ukrainian refugees have fled to Poland alone.2

The initial response of the UK government has been slow and extremely bureaucratic, but the UK now must do more to help refugees of all ages. The recently launched ‘Homes for Ukraine’ scheme, which offers £350 a week to households to house refugees, is a step in the right direction.3

Refugee experience and needs

The UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR) estimates that around 70 million people are forcefully displaced around the world. The war in Ukraine is adding several million more refugees to this number.

While the humanitarian rationale for helping refugees is obvious, it is also important to understand the needs of refugees beyond their mere survival, shelter, and food. Refugees are not just another group of immigrants. They did not have months or even years to plan a move across international borders, as economic migrants might have.

Instead, the trauma of forced displacement comes with a series of additional experiences and needs (Becker and Ferrara 2019):

- First, refugees have undergone and still undergo physical or psychological pain to an extent not experienced by voluntary migrants.

- Second, refugees have lost their assets as a result of destruction or because they had to leave their home – often quickly – without much hope of returning.

- Third, refugees often end up in sub-optimal locations; their first concern is to ‘get out’ and their choices over where to go are often limited. Just think of the UK’s focus on giving visas to those Ukrainians who have family connections in the UK. How about those without family connections who, for whatever reason, want to make the UK their new home?

- Fourth, refugees often have no control over whether their new location is temporary or permanent, which makes planning one’s future harder. In the case of Ukraine, many may wish to return but will be unable to do so until it is safe – and it is unclear when that will be.

In these circumstances, one important aspect is education. This is because refugees who have lost all their physical belongings and have been uprooted from their homeland may wish to invest in the one (portable) asset that no one can take away from them: education (Becker et al. 2020a).

This applies to both adults and children. Adult Ukrainians are likely to want to learn the language of their new home country, as well as invest in developing vocational skills that will allow them to make the most of their new environment.

One group that deserves particular attention is refugee children. Around the world, the educational needs of refugee children are often overlooked as politicians in host countries focus on giving refugees food and shelter.

The UNHCR estimates that among the 20.7 million refugees under their immediate care, many in less developed areas of the world, 7.9 million are refugee children of school age.4 Their access to education is limited, with almost half of them unable to attend school at all.

Even in Europe, immediate and full access to education for refugee children is by no means a given. In Germany, which welcomed more than one million Syrian refugees after Angela Merkel’s famous “We can do it!” (“Wir schaffen das!”), state governments struggled to provide access to education for all refugee children. Some waited for nearly a year to go to school (Rod 2019).

What does history teach us about the importance of full and immediate access to education for refugee children?

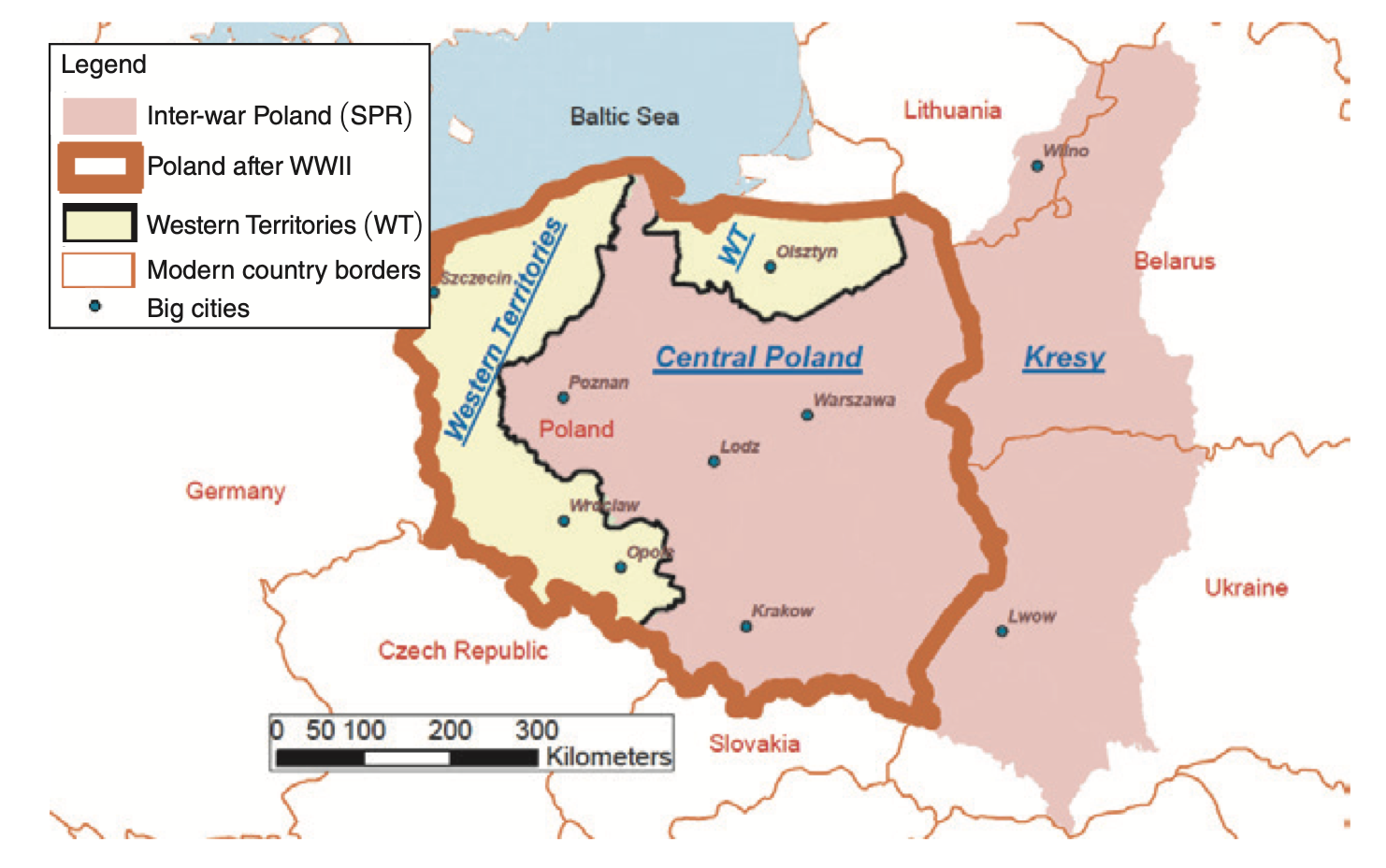

During and after WWII, millions of Europeans were displaced and forcefully resettled hundreds, if not thousands, of kilometres from their homes as a result of massive border changes. In the aftermath of the war, over two million Poles were expelled from their homes when Polish frontiers were moved westward. Figure 1 illustrates Poland’s redrawn borders.

Figure 1 Map of Poland during WWII

Source: Becker et al. (2020a)

Poland’s Eastern territories (Kresy) became part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), concretely the Ukrainian, Belarussian, and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republics – the same part of the world that is now again at the centre of a massive war.

At the same time, former German areas (the Western Territories) became Polish. Before WWII, the Western Territories were home to about eight million Germans, who were forced to resettle after the war, leaving land and capital stock behind. In the east, Poles were forced to leave Kresy and the vast majority resettled in the now sparsely populated (formerly German) Western Territories.

Can the experience of being uprooted by force encourage people to invest in portable assets such as education? Economic researchers have long entertained the idea that being uprooted by force or expropriated increases the subjective value of investing in portable assets, in particular in education (e.g. Brenner and Kiefer 1981).

This notion is also popular outside academic spheres. In his bestselling autobiographical novel, A Tale of Love and Darkness, Amos Oz gives a testimony of how a history of forced migration has made Jewish families put a lot of emphasis on education as the “only thing that no one can ever take away from your children, even if, Heaven forbid, there’s another war, another revolution, more discriminatory laws.”

The Polish experience of forced migration after WWII shows strong evidence for the ‘uprootedness hypothesis’. Polish people with a family history of forced migration as a result of the war are significantly more educated today than any comparison group.

This result suggests a shift in preferences toward investment in human capital rather than physical capital, and it implies that the benefits of providing schooling for forced migrants and their children may be even greater – and more persistent – than previously thought.

What is the lesson for the UK today? Above and beyond the moral imperative to help all refugees fleeing from an evil war, it is of paramount importance to give refugees immediate and unhindered access to schooling.

Every week that refugees spend in temporary shelters may lead to hesitancy by education authorities to provide places at school until there is more clarity about the long-term living arrangements and address. But every week is a week lost.

If a history of mass displacement in Europe carries any lessons for today (Becker 2022), refugees, and by extension their children, will be keen to make the most of a traumatic experience. Access to education can be a silver lining of forced migration (Becker et al. 2020b), allowing refugee children to invest in a brighter future.

References

Becker, S O and A Ferrara (2019), “Consequences of forced migration: A survey of recent findings”, Labour Economics 59: 1-16.

Becker, S O, I Grosfeld, P Grosjean, N Voigtländer and E Zhuravskaya (2020a), “Forced migration and human capital: Evidence from post-WWII population transfers”, American Economic Review 110(5): 1430-1463.

Becker, S O, I Grosfeld, P Grosjean, N Voigtländer and E Zhuravskaya (2020b), “A silver lining of forced migration: Investment in education”, VoxEU.org, 28 January.

Becker, S O (2022), “Forced displacement in history: Some recent research”, Australian Economic History Review 62(1): 2-25.

Brenner, R and N M Kiefer (1981), “The economics of the diaspora: Discrimination and occupational structure”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 29(3): 517-534.

Oz, A (2002), A Tale of Love and Darkness, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Rod, J (2019), “Education for refugee children”, Deutschlandfunk, 29 April.

Endnotes

1 Source: UNHCR Operational Data Portal on Ukraine Refugee Situation

2 Source: UNHCR Operational Data Portal on Ukraine Refugee Situation

3 See https://www.gov.uk/government/news/homes-for-ukraine-scheme-launches

4 Source: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/education.html