On 21 June 2018, euro area governments negotiated a debt relief agreement for Greece. It deferred repaymentof €96 billion of bailout loans by 10 years, but left the door open tolink further debt relief for Greece to the country’s economic performance. Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the IMF, welcomed the deal but had “reservations” about Greece’s longer-term debt sustainability. Mario Draghi, the president of the ECB, said that he welcomed the readiness of finance ministers "to consider further debt measures … in case adverse economic developments were to materialise” (Financial Times 2018).

This long-awaited plan for Greece does not address face-value debt reduction. We know that the specific characteristics of sovereign debt renegotiations are important, because they may have significant long-run economic implications.

The literature on sovereign debt has commonly assumed sovereign defaults and debt restructuring are not costless. The economic costs of a sovereign's unilateral decision to stop servicing its debt, it argues, are a government's main incentive to honour its debt obligations.

Empirical research on sovereign defaults, however, has generally found that default costs are difficult to quantify and short-lived. This research has mainly looked at their effects on international trade, the international credit market and GDP growth. But by including a measure of investors' losses in their analysis, Cruces and Trebesch (2013) showed that restructuring involving higher haircuts was associated with significantly higher subsequent bond yield spreads, and longer periods of capital market exclusion.

What we know about private and official restructuring

An emerging body of research is devoting more attention to the heterogeneity of debt restructuring strategies, and to specific analyses of individual country repayment records. For example, it distinguishes between what we can call 'private' restructuring deals that involve foreign banks and bondholders, and 'official' restructuring, by bilateral and multilateral creditors. This distinction is important because private and official settlements have different characteristics. Official restructurings, generally arranged under the umbrella of the 'Paris Club', should in theory guarantee a smoother approach when orchestrating deals than private ones.

Whether private or official, the economic consequences of these debt restructurings have been investigated, focusing on their economic growth outcomes. In the private sector, pre-emptive restructurings – implemented before a payment default – are more frequent and quicker to negotiate. They have been associated with lower haircuts and lower output losses (Asonuma and Trebesch 2016). The authors found that hard defaults – involving a confrontational relationship between creditors and debtors – were associated with a much steeper drop in output.

Surprisingly, however, Trebesch and Zabel (2017) found that after five years, neither high haircuts nor coercive relationships with debtors were associated with lower growth. Reinhart and Trebesch (2016) analysed both private (Latin American countries through the Brady Plan) and official (European nations during the 1930s) restructurings. They found that only debt write-offs are able to improve the economic situation of debtor countries, and that softer forms of debt relief, such as maturity extensions or interest rate reductions, did not improve the situation. Forni et al. (2016) found that private restructurings were, in general, bad for growth unless they allowed a country to exit a default period. In particular, they found that debt relief had the largest growth impact for countries that exited default with relatively low levels of debt.

In the official sector, Cheng et al. (2018), agreed with Reinhart and Trebesch (2016) that Paris Club agreements have had a significant impact on economic growth, but only if the debt treatment involved nominal haircuts.

Comparing the private and official

In our recent work (Marchesi and Masi 2018) we compare the growth outcome of official and private restructuring (as well as debt flow and stock effects) by estimating the impact of both types of restructuring to the same country. The sample of countries we consider is larger than, and different to, the advanced economies in the 1930s plus the 'Brady countries' during the 1990s that Reinhart and Trebesch (2016) considered.

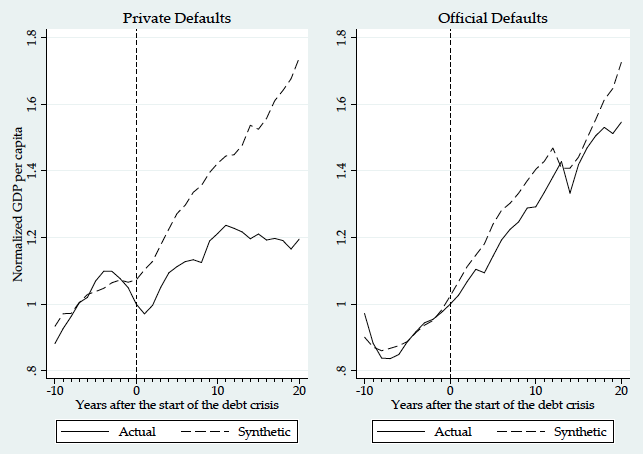

By analysing about 500 restructuring episodes between 1975 and 2014, we find that private and official defaults may have different growth outcomes. Figure 1 shows that, while private defaults are generally associated with lower growth during the crisis and over the long run, we do not find a growth contraction for official defaulters, either throughout the years of the crisis or in the long run.

Figure 1 Average effects of private and official defaults

Source: Marchesi and Masi (2018).

Notes: Solid lines depict the average GDP per capita of a sample of private and official defaulters. Dashed lines show the GDP per capita that the defaulting countries would have reached in the absence of a debt crisis.

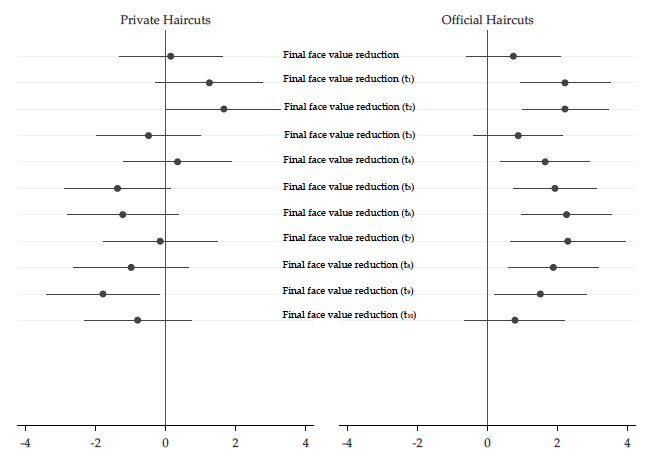

When debt relief operations also involve debt write-offs, this blurs the negative relationship between private default and growth. Growth rates for official defaulters strongly benefit. Figure 2 tracks the evolution over time of the size, sign and significance of the coefficients denoting both private and official final restructuring deals, in the case of face value reduction. Coefficients were obtained using a GLS regression.

Figure 2 Evolution over time of growth rates after a face-value reduction, private and official

Source: Marchesi and Masi (2018).

The importance of face-value debt reduction

Our results support Asonuma and Trebesch (2016) and Trebesch and Zabel (2017), who stressed the importance of the way in which debt restructurings are orchestrated, because the level of confrontation between creditors and debtors might have persistent effects. If restructuring agreements such as Paris Club or Brady deals represent 'soft' default, our evidence suggests that they may be associated with higher growth long-run growth rates, especially after a face-value reduction.

In Greece, private debt has been replaced by official debt. These results provide important insight for the debate on granting Greece further official debt relief in the future, and on the importance of face-value debt reduction to help Greece, and other economies, recover.

References

Asonuma, T and C Trebesch (2016), "Sovereign Debt Restructurings: Pre-emptive or Post-Default", Journal of the European Economic Association 14: 175-214.

Cheng, G, J Diaz-Cassou, and A Erce (2017), "From Debt Collection to Relief Provision: 60 Years of Official Debt Restructurings through the Paris Club", Inter-American Development Bank working paper 753.

Cheng, G, J Diaz-Cassou, and A Erce (2018), "The Macroeconomic effects of Official Debt Restructuring: Evidence from the Paris Club", Oxford Economic Papers, forthcoming.

Cruces J J and C Trebesch (2013), "Sovereign Defaults: The Price of Haircuts", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5: 85-117.

Financial Times (2018), "Eurozone creditors reach ‘historic’ deal on Greek debt relief", 22 June.

Marchesi S and T Masi (2018a), Life after default: Official vs. private sovereign debt restructurings, Centro Studi Luca d'Agliano working paper 437.

Marchesi S and T Masi (2018b), Sovereign ratings after sovereign restructurings: official vs private default, mimeo.

Reinhart, C M and C Trebesch (2016), "Sovereign Debt Relief and its Aftermath", Journal of the European Economic Association14(1): 215-251.

Trebesch C and M Zabel (2017), "The Output Costs of Hard and Soft Sovereign Default", The European Economic Review92: 416-432.