As climate change looms ever larger (IPCC 2018a, Furman et al. 2015), economists have coalesced around the need for climate policies centring around Pigouvian taxes cushioned by transfers to vulnerable households (IMF 2020, Gollier 2021).1 However, carbon taxes and related policies face deep political constraints (Nordhaus 2015, Gillingham and Stock 2018). As a complement to policies directly targeting carbon emissions, many look to sustainable investing – increasingly identified with the incorporation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns in investment strategies – as part of the way forward (Krueger et al. 2020, Hong et al. 2021). In recent work, we examine whether such market forces can help make meaningful progress in addressing climate change (Elmalt et al. 2021).

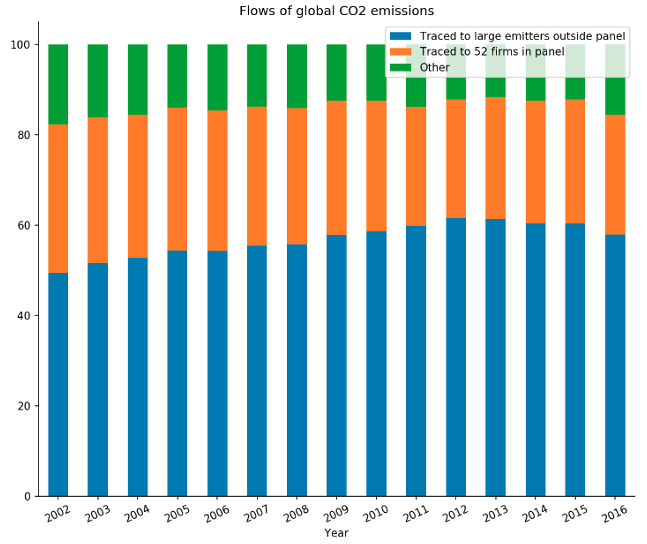

While climate change is a global challenge, much of the global stock of carbon emissions can be traced to a remarkably small set of firms: just 96 firms located upstream in production chains reliant on carbon emissions (largely fossil fuel producers) have accounted for 70% of global carbon emissions since 1850 (Figure 1). This striking concentration motivates us to focus on the potential for ESG investing to shift production incentives within these ‘climate-crucial’ firms.

To assess scope for ESG-conscious investing to affect production decisions, we combine firm-level data on emissions for large emitters with data on ESG metrics and other firm characteristics and end up with a panel covering 52 investor-owned firms in 20 countries accounting for close to 30% of global emissions since 2002.2 Industry-level comparisons suggest that these firms are attuned to ESG considerations – they receive better overall ESG ratings than listed firms in other industries.

Figure 1 Flow of global carbon emissions traced to large emitters

Notes: This figure shows the flow of global carbon emissions, breaking out emissions attributable to the 52 large emitters in our baseline panel and to the remaining large emitters tracked in our firm-level emissions data (Heede 2014a, 2014b). Emissions are shown as shares of the total flow in each year.

A weak link: ESG scores and emissions

In principle, concerned investors wishing to shift production incentives for these large investor-owned emitters could strongly condition their investment decisions on ESG indicators (Oehmke and Opp 2020).3 A basic prerequisite for such a strategy to be effective is that changes in these firms’ contributions to climate change need to be reflected in ESG scores. Large emitters that cut – or promise to cut – their emissions would then receive high ESG scores, attract fresh funds from ESG investors, and lower their cost of capital. Conversely, firms that continue to make ‘dirty’ investments, penalised via poor ESG scores, would face higher costs of capital due to waning interest from ESG investors. This dynamic could generate a virtuous cycle in which firms with higher ESG scores have slowing emissions and vice versa.

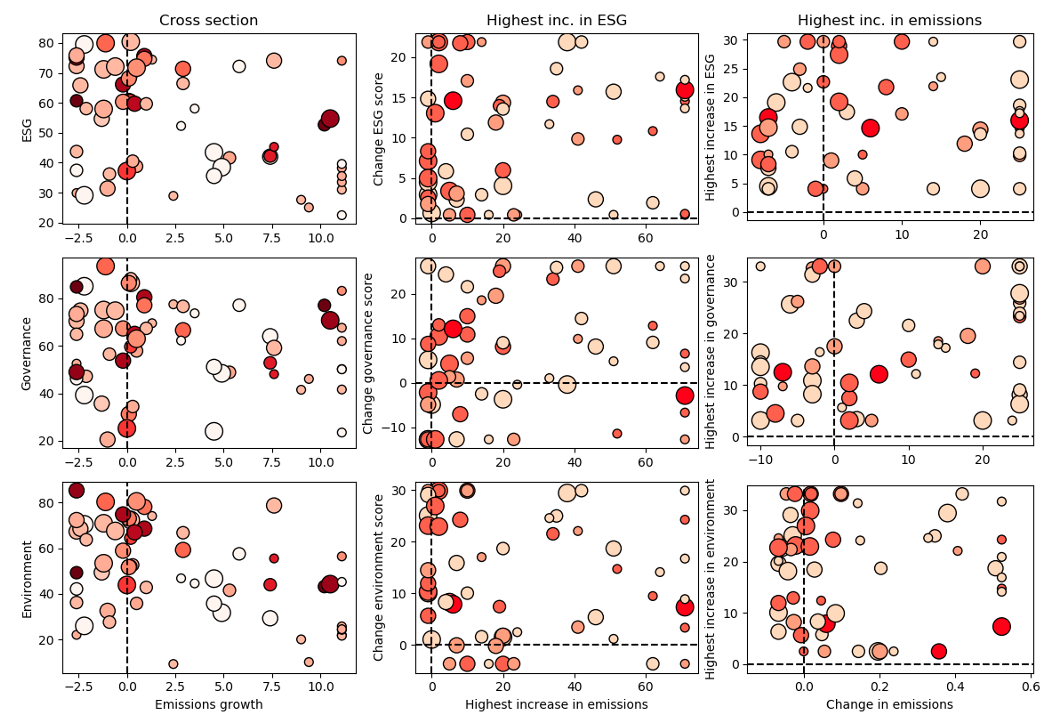

Discouragingly, ESG scores do not appear to capture differences in emissions growth across large emitters. ESG scores and emissions growth do vary significantly within the panel. The interquartile range of emissions growth across large emitters is 10.4% (meaningful even in comparison to countries’ Paris agreement pledges to slow emissions growth) (Carbon Brief 2017). However, ESG scores appear largely unrelated to emissions growth (Figure 2). This lack of relationship does not depend on whether we focus on the overall panel, on large changes in ESG scores or emissions, or on similar comparisons based on emissions scaled by revenues or assets.

Figure 2 ESG and emissions growth in the cross-section

Notes: This figure shows ESG scores and emissions growth in the cross section. The first row shows overall ESG scores. The second and third rows show scores for the Governance and Environment pillar respectively. The left column shows averages over the full sample. The middle column shows averages for the four year period with the largest increase in emissions. The right column instead shows averages in the four year period with the largest improvement in ESG scores. Bubble sizes represent the average absolute size of emissions. Shading indicates economic conditions: darker red represents slower economic growth. Outliers are trimmed.

More formal analysis uncovers at best a weak relationship between ESG scores and emissions growth. Our baseline regressions examine the link between emissions growth and ESG scores at the firm-year level, controlling for firm characteristics, macroeconomic conditions, and year fixed effects. Large emitters with better ESG scores do display somewhat slower emissions growth (this link is largely tied to governance scores rather than environment scores). But the link between ESG scores and emissions growth is substantially attenuated if we rely on within-country or within-firm variation. The lack of a within-firm connection is important: large emitters that reduce (increase) emissions growth do not appear to be consistently rewarded (penalised) by better (worse) ESG scores.

ESG is not enough

Next, we consider a thought experiment. To the extent there is a connection between ESG scores and emissions growth, is its scale meaningful relative to the climate change problem? Ongoing rapid growth in ESG investing may incentivise large emitters to improve their ESG scores by cutting their emissions. Unfortunately, even with our largest estimates, the reduction in emissions associated with a hypothetical large collective improvement in ESG scores would do little to meaningfully help mitigate climate change. According to scenarios prepared by the IPCC (2018b), with emissions growing in line with historical trends, in just 14 years the odds that warming can be limited to one point five degrees Celsius would be worse than even. Allocated proportionately, even a two standard deviation improvement in ESG scores would correspond to slowing emissions growth enough to buy only two more years before this climate objective would be out of reach.

ESG investing has grown dramatically in recent years, in large part motivated by growing attention to climate change (see Starks 2020 and Cornell and Damodaran 2020 for engaging reviews of the burgeoning academic literature on ESG investing). Signatories to the Principles for Responsible Investing – with some US$80 trillion in assets under management in 2019 – report that ESG considerations are integrated into investment decisions for three-quarters of assets under management (Matos 2020). Many of these investors appear to actively target portfolio allocations towards firms with higher ESG scores (Gibson et al. 2020). Particularly relevant for our work, large asset managers cognisant of climate risks report that they are strongly focused on firms' ESG ratings (Krueger et al. 2020). Indeed, the cost of capital rises for firms with poor environment pillar scores with prominent shifts in the global climate policy discussion (Seltzer, Starks & Zhu 2020).

However, our findings suggest that there is limited scope for sustainable investing strategies conditioned (solely) on ESG indicators to meaningfully shift production incentives for large emitters. ESG scores overall—as well as environment pillar scores—do not link tightly with emissions growth for major emitters, suggesting that these scores may not deliver what investors expect them to. This could reflect fundamental constraints with data availability due to the lack of consistent reporting. The multidimensional nature of the ESG approach may also place constraints.4 Some investors may also not be aware that important components of ESG scores often compare firms to competitors in the same industry, providing relative rather than absolute rankings. Environmentally conscious investors and policymakers should approach ESG investing with caution.

Conclusions

Many commentators and policymakers have called for more robust disclosure requirements for climate risk (IMF 2019). More attention to consistently reported measures directly connected to contributions to climate change is likely to help (e.g. Ehlers et al. 2020). While consistent reporting standards and requirements for all firms would be valuable, sustained efforts from third-party researchers mean that data is not a key constraint for the important set of firms we study: Investors concerned about climate change can directly focus on emissions growth to evaluate both these firms and asset management products that incorporate them.5 However, such approaches continue to face important challenges, highlighting the need to continue to build consensus towards effective economy-wide policies to address climate change.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Berg, F, J F Koelbel and R Rigobon (2020), “Aggregate confusion: the divergence of ESG ratings”, MIT Sloan School Working Paper 5822-19.

Broccardo, E, O Hart and L Zingales (2020), “Exit vs. voice”, NBER Working Paper w27710.

Carbon Brief (2017), “Paris 2015: Tracking country climate pledges”, CarbonBrief.org, 2 June.

Cornell, B and A Damodaran (2020), “Valuing ESG: Doing good or sounding good?”, Mimeo.

Christensen, D, G Serafeim and A Sikochi (2019), “Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder? the case of ESG ratings”, The Accounting Review.

Ehlers, T, B Mojon, F Packer and L A P da Silva (2020), “Green bonds and carbon emissions: Exploring the case for a rating system at the firm level”, VoxEU.org, 12 December.

Elmalt, D, D Igan and D Kirti (2021), “Limits to Private Climate Change Mitigation”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP16061.

Furman, J, R Shadbegian and J Stock (2015), “The cost of delaying action to stem climate change: A meta-analysis”, VoxEU.org, 25 February.

Gollier, C (2021), “Efficient carbon pricing under uncertainty”, VoxEU.org, 06 April.

Gibson, R, S Glossner, P Krueger, P Matos and T Steffen (2020), “Responsible institutional investing around the world”, Mimeo.

Gibson, R, P Krueger and P S Schmidt (2021), “ESG rating disagreement and stock returns”, Research Paper Series No 19-67, Swiss Finance Institute.

Gillingham, K and J H Stock (2018), “The cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 32(4), 53-72.

Heede, R (2014a), “Carbon majors: Accounting for carbon and methane emissions 1854-2010”, Methods & results report, Climate Mitigation Services.

Heede, R (2014b), “Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854-2010”, Climatic Change 122(1-2), 229-241.

Hong, H, N Wang and J Yang (2021), “Welfare consequences of sustainable finance”, NBER Working Paper w28595.

IPCC (2018a), “Summary for policymakers”, in Masson-Delmotte, V, P Zhai, H-O Prtner, D Roberts, J Skea, P R Shukla, A Pirani, W Moufouma-Okia, C Pan, R Pidcock, S Connors, J B R Matthews, Y Chen, X Zhou, M I Gomis, E Lonnoy, T Maycock, M Tignor and T Waterfield (eds), Global Warming of 1.5C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, World Meteorological Organization, pp. 1-32.

IPCC (2018b), “Mitigation pathways compatible with 1.5c in the context of sustainable development”, in Masson-Delmotte, V, P Zhai, H-O Prtner, D Roberts, J Skea, P R Shukla, A Pirani, W Moufouma-Okia, C Pan, R Pidcock, S Connors, J B R Matthews, Y Chen, X Zhou, M I Gomis, E Lonnoy, T Maycock, M Tignor and T Waterfield, (eds) Global Warming of 1.5C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, World Meteorological Organization, pp. 93-174.

International Monetary Fund (2019), “Sustainable finance”, Global Financial Stability Review, Chapter 6.

International Monetary Fund (2020), “Mitigating climate change—growth and distribution-friendly Strategies”, World Economic Outlook, Chapter 3.

Krueger, P, Z Sautner and L T Starks (2020), “The importance of climate risks for institutional investors”, The Review of Financial Studies 33(3), 1067-1111.

Matos, P (2020), “ESG and responsible institutional investing around the world”, Literature review, CFA Institute Research Foundation.

Naaraayanan, S L, K Sachdeva and V Sharma (2020), “The real effects of environmental activist investing”, European Corporate Governance Institute – Finance Working Paper No. 743/2021.

Nordhaus, W (2015), “Climate clubs: Overcoming free-riding in international climate policy”, American Economic Review 105(4), 1339-70.

Oehmke, M and M M Opp (2020), “A theory of socially responsible investment”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP14351.

Seltzer, L, L Starks and Q Zhu (2020), “Climate regulatory risks and corporate bonds”, Nanyang Business School Research Paper No. 20-05.

Starks, L (2020), “Climate risk and investors”, Keynote address, 2020 FMA Virtual Conference.

Wall Street Journal (2019), “Economists’ Statement on Carbon Dividends”, WSJ.com, 24 June.

Endnotes

[1] See a 2019 Wall Street Journal statement by a group of prominent economists in support of carbon taxes with lump sum rebates.

[1] We exclude large emitters directly controlled by national governments. These firms are largely unaffected by sustainable investing.

[1] Broccardo et al. (2020) refer to this approach as exit. Alternatively, shareholders could also use voting power (their ‘voice’) to influence emitting firms’ actions. As many investors focused on climate change risks pay attention to ESG ratings (Krueger et al. 2020, Matos 2020), our results are relevant for both approaches.

[1] Several researchers have noted disagreements across providers of ESG scores (Berge et al. 2020, Gibson et al. 2021, IMF 2019, Christensen et al. 2019), albeit with smaller disagreements about environment pillar scores than on other pillars (Gibson et al. 2021).

[1] Naaraayanan et al. (2020) show that some sophisticated investors have already conditioned activism campaigns on measures of potential future emissions rather than ESG scores.