The nine months in-utero is one of the most critical periods for human skill formation, and even mild shocks during this period can leave long-lasting imprints on future human capital and health of exposed children (Almond and Currie 2010, 2011). The foetal origins literature has linked in-utero exposure to shocks such as nutritional deprivation – for example, during the Dutch famine of 1944–1945 (Scholte et al. 2015, Conti et al 2021, 2022) – and maternal stress – for example, induced by high local homicide rates (Koppensteiner and Manacorda 2016) – to worse health and economic outcomes later in life.

Growing attention has been received by in-utero exposure to the Ramadan fast, which is a relatively mild shock but affects nearly 1.35 billion people globally. Observing fast during the lunar month of Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam and therefore obligatory for all Muslims other than a few exempt categories. The fast, which involves abstaining from food and drinks from sunrise to sunset, stresses the maternal environment by changing the mother’s eating and sleeping patterns, disrupting the steady supply of nutrients to the foetus. In-utero exposure to the Ramadan fast has been linked to lower birth weight (Almond 2009, Almond and Mazumder 2011), lower educational attainment (Almond et al. 2014, Majid 2015), and worse health outcomes later in life (Almond 2009, Almond and Mazumder 2011, van Ewijk 2011). However, evidence on the long-term labour market impacts on exposed individuals and on the underlying mechanisms is limited (Mahanani et al. 2021).

Evidence from Pakistan’s administrative tax records

Establishing causal links between the in-utero environment and long-term outcomes is not straightforward, especially due to two empirical challenges. First, mild shocks such as nutritional deprivation, disease, or stress may not leave strong observable markers, especially if the outcomes are measured a long time after the shock. The second challenge is that shocks to the in-utero environment are rarely exogenous, i.e. they are likely to affect poor families more than the rich. In the context of Ramadan fasting, the concern is that parents with certain socioeconomic characteristics may time their pregnancies to limit or avoid Ramadan exposure of their children.

In our recent paper (Cejka and Waseem 2022), we overcome the measurement challenge by using administrative tax data from Pakistan. The tax data, which comprise the universe of income tax returns filed in 2007–2009, reduces measurement error and provides us with high statistical power. It also allows us to estimate treatment effects on economically relevant labour market outcomes including earnings and occupational choice.

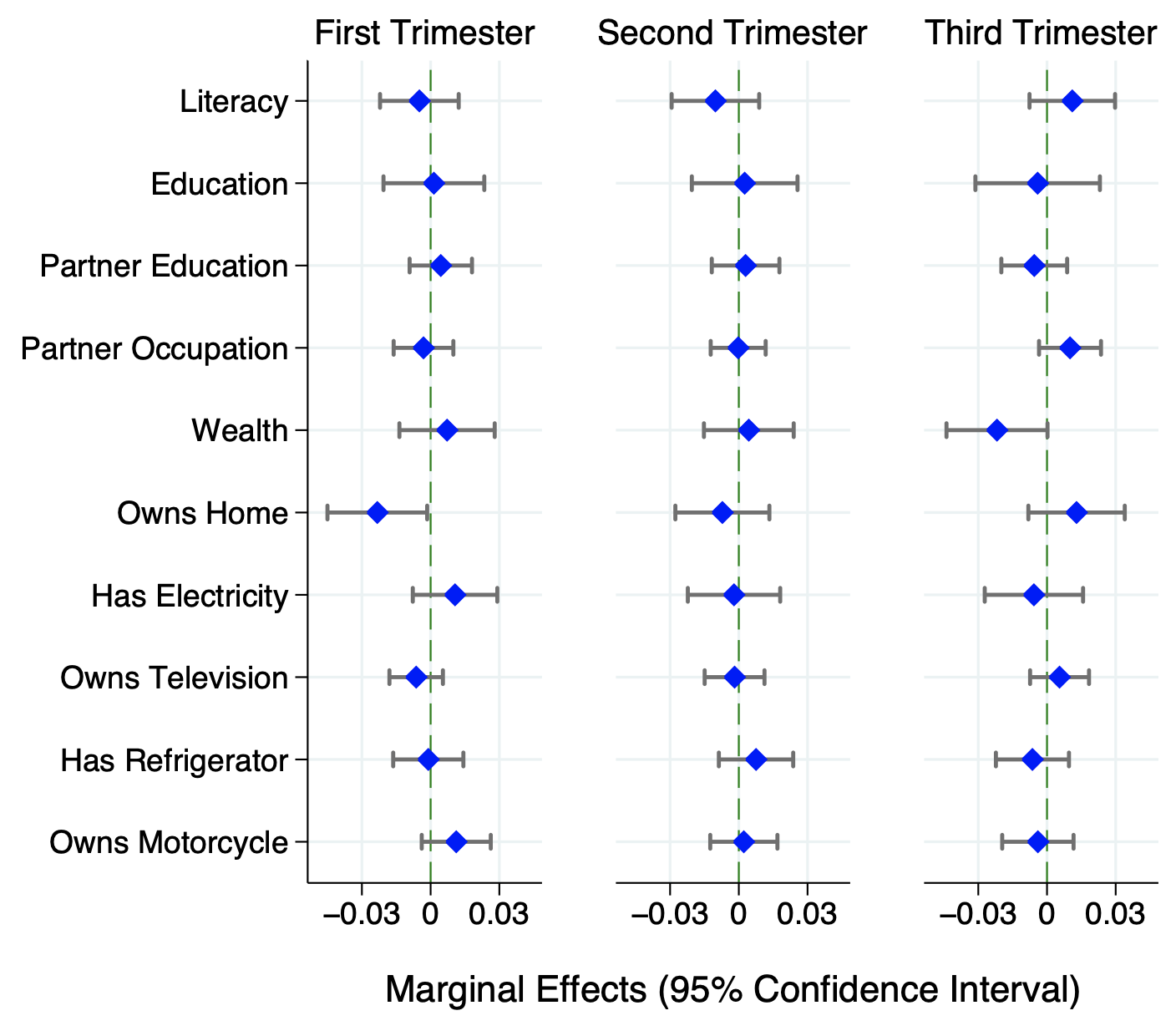

We overcome the identification challenge by exploiting a plausibly exogenous shock created by Ramadan fasting. Using linked parent-child data from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), we show that in-utero exposure to Ramadan fasting is uncorrelated with parental characteristics such as wealth or education. For example, we estimate a multinomial logistic model that tests if parental characteristics predict an individual’s Ramadan exposure in one of the three trimesters of pregnancy, using the unexposed and only partially exposed groups as the reference category. Figure 1 presents the marginal effects from this model, showing that parental characteristics have no predictive power on Ramadan exposure.

Figure 1 Selection into in-utero Ramadan exposure?

Our empirical strategy relies on the fact that Ramadan follows the lunar calendar, which is shorter than the solar calendar by 11 days. Due to the normal length of gestation, children conceived in 9 out of 12 months of a year are exposed to the lunar month of Ramadan at some point while in-utero. This gives us an ideal empirical setting with natural control groups: we can compare labour market outcomes of exposed and unexposed individuals. To make granular comparisons, we compare these groups after conditioning on their district, month, and year of birth. Since our data contain a large span of birth cohorts, we can control for the confounding effects of seasonality nonparametrically. Specifically, the fact that we observe individuals born across 66 years and that Ramadan completes a full cycle across the solar calendar in 33 years allows us to disentangle the effect of Ramadan fasting from seasonal effects.

Lower earnings later in life

Our analysis of earnings reveals two key results. First, in-utero exposure to Ramadan fasting has a significant negative effect on earnings. We estimate over 30 specifications and in each case we can reject the null hypothesis that Ramadan exposure in any of the pregnancy months has no effect on earnings. Second, the effect size varies with the pregnancy month of exposure, with individuals exposed in months 3-8 being the worst affected, earning at least 2-3 percent less on average than the unexposed.

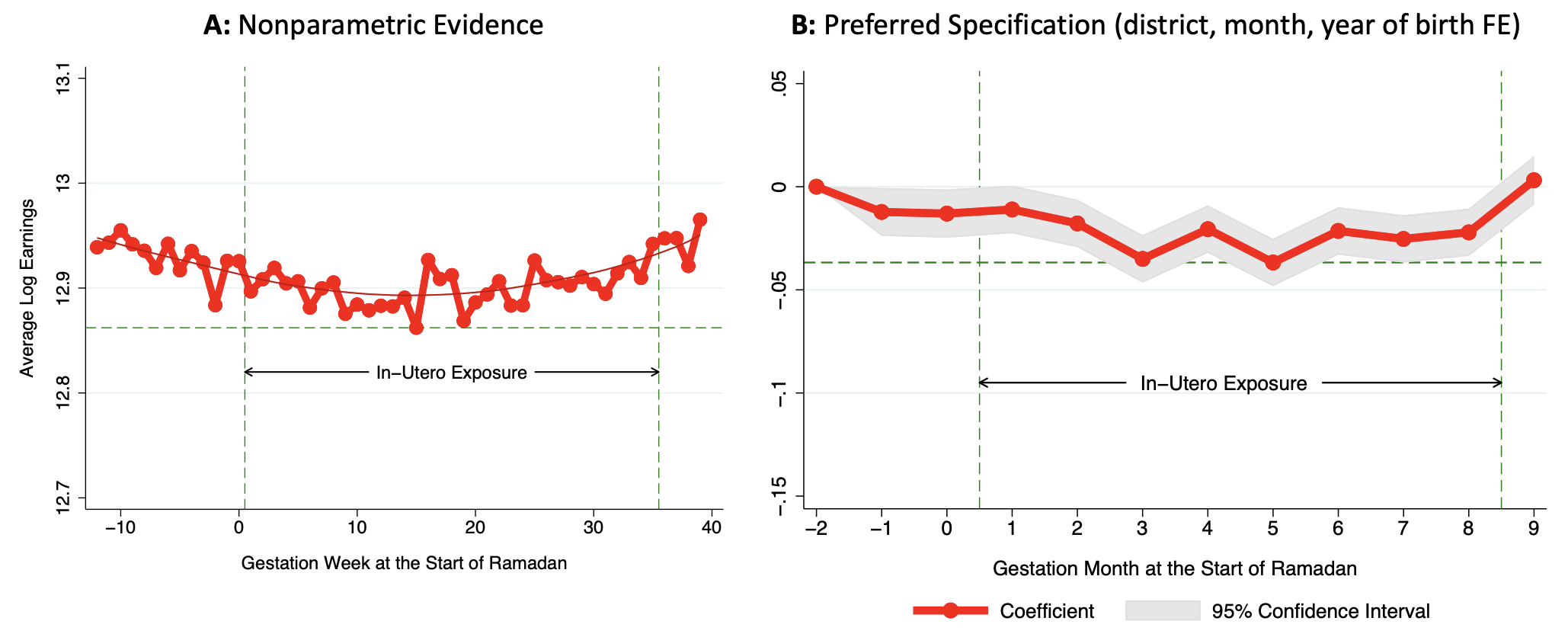

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between earnings and in-utero Ramadan exposure. Both panels reveal that earnings fall with Ramadan exposure, reaching a minimum in the middle period of pregnancy, before recovering essentially to the same level as the unexposed in the final period of pregnancy.

Figure 2 In-utero Ramadan exposure and earnings

Note: We divide our sample into groups based on their period of conception relative to Ramadan using weeks in Panel A and months in Panel B. For example, in Panel B, individuals corresponding to months -2 and -1 are unexposed, month 0 are partially exposed, and months 1 to 9 are exposed in pregnancy months 1 to 9 respectively. Panel A presents a non-parametric scatterplot of average log earnings by Ramadan week of exposure; Panel B formalizes these results in a regression-based framework using our preferred set of controls.

Since we don’t observe fasting behaviour in our tax data, our estimates are intention-to-treat effects, which we interpret as lower bounds for the average treatment effect (for more detail, see Cejka and Waseem 2022). Surveys of Pakistan pregnant women show that only around one-third of them fast for the whole month of Ramadan (Mubeen et al. 2012, Nusrat et al. 2017, Masood et al. 2018). Given our intention-to-treat estimates, the average treatment effect of in-utero Ramadan exposure can therefore be as high as 9% of earnings, assuming that the treatment effect is homogeneous in the population.

Importance of the skills channel

There are two main mechanisms by which Ramadan fasting in-utero could have a negative impact on earnings: the skills channel and the health channel. A causal story according to the skills channel maintains that the exposed children are born with lower capacities to produce cognitive and non-cognitive skills, which leads them to attain less education, make dominated occupational choices, and earn less income. Under the health channel, lower earnings of exposed individuals arise out of their worse health. For example, exposed individuals may possess lower vitality and vigour than the unexposed, leading them to come up short in the labour market.

On balance, our evidence suggests that the earnings effect mediates through the skills channel, although we cannot rule out the importance of the health channel. In particular, we find that exposed children indeed make dominated occupational choices. Specifically, they are significantly less likely to be employees (rather than self-employed) or in high-skilled occupations, which require professional qualifications. They are significantly more likely to be in retail and wholesale trade, industries with proportionally the most low-skilled jobs. In our population, occupational choice and educational attainment are tightly correlated. The sign and magnitude of these correlations suggest that exposed children are likely to possess significantly less education than the unexposed. This lower human capital reflects in their occupation choice, position in the income distribution, earnings, as well as their earnings within occupations.

Concluding remarks

Our evidence suggests that large Pareto gains can be made by making families aware that (1) Ramadan fasting is not obligatory for pregnant women, so that they can postpone it to a later period without violating any religious injunctions; and (2) Ramadan fasting by pregnant mothers can have long-run negative effects on human capital and labour market outcomes of children. Survey evidence shows that a vast majority of women are not aware of these two facts (e.g. Mubeen et al. 2012). Eliminating these misperceptions through targeted interventions could therefore be a cost-effective way to improve outcomes. It is, however, not clear if such misperceptions are a type of protected beliefs and hence less amenable to informational interventions. Future work may look at the nature of these misperceptions as well as study other investments that would be most cost effective in terms of improving exposed children’s future outcomes.

References

Almond, D (2009), “The effect of maternal fasting during pregnancy”, VoxTalk, 6 November.

Almond, D and Currie, J (2010), “The long-term impact of life before birth”, VoxEU.org, 24 June.

Almond, D and Currie, J (2011), “Killing Me Softly: The Fetal Origins Hypothesis”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(3): 153–172.

Almond, D and B Mazumder (2011), “Health Capital and the Prenatal Environment: The Effect of Ramadan Observance during Pregnancy”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(4): 56–85.

Almond, D, B Mazumder and R Van Ewijk (2014), “In Utero Ramadan Exposure and Children’s Academic Performance”, The Economic Journal 125(589): 1501–1533.

Cejka, T and M Waseem (2022), “Long-Run Impacts of In-Utero Ramadan Exposure: Evidence from Administrative Tax Records”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17176.

Conti, G, P Ekamper and S Poupakis (2022), “The long-lasting health effects of severe shocks during pregnancy”, VoxEU.org, 21 Feb.

Conti, G, S Poupakis, P Ekamper, G E Bijwaard and L H Lumey (2021), “Severe Prenatal Shocks and Adolescent Health: Evidence from the Dutch Hunger Winter”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16633.

Koppensteiner, M and M Manacorda (2016), “The effect of day-to-day violence on infant health”, VoxEU.org, 18 April.

Nusrat, U, S Rabia, R Tabassum and S Rafiq (2017), “Beliefs and Practices of Fasting in Ramadan Among Pregnant Women”, Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences, 15.

Mahanani, M R, E Abderbwih, A S Wendt, A Deckert, K Antia, O Horstick, P Dambach, S Kohler, and V Winkler (2021), "Long-Term Outcomes of in Utero Ramadan Exposure: A Systematic Literature Review", Nutrients 13(12): 4511. .

Majid, M F (2015), “The persistent effects of in utero nutrition shocks over the life cycle: Evidence from Ramadan fasting”, Journal of Development Economics 117: 48–57.

Masood S N, S Saeed, N Lakho, Y Masood, M Y Ahmedani, A S Shera (2018), “Pre-Ramadan health seeking behavior, fasting trends, eating pattern and sleep cycle in pregnant women at a tertiary care institution of Pakistan”, Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 34(6): 1326-1331.

Mubeen, S M, S Mansoor, A Hussain and S Qadir (2012), “Perceptions and practices of fasting in Ramadan during pregnancy in Pakistan”, Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 17(7): 467.

Scholte, R S, G J Van den Berg, and M Lindeboom (2015), “Long-run effects of gestation during the Dutch hunger winter famine on labor market and hospitalization outcomes”, Journal of Health Economics 39: 17–30.

van Ewijk, R (2011) “Long-term health effects on the next generation of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy”, Journal of Health Economics 30(6): 1246–1260.