The Inca Empire was the last and greatest in a long series of highly developed cultures in pre-colonial South America. The Inca Road has played a particularly important part in the region’s history. Not only did it play a major role during the Inca Empire but it was a key component of the economy when most of South America was under Spanish rule. Unlike how they treated the Inca’s agriculture or language, the Spaniards incorporated the road system into their trade-based economy and merged it with their own institutions. It was thus a linchpin of the colonial economy in the New World (Glave 1989).

Despite the role the Inca Road played in both the past and present, its impact on current development has not been studied in great depth, although the economic literature has established the fact that historical institutions can have long-lasting effects. In our new paper (Franco et al. 2021), we therefore undertake the first empirical examination of how the Inca Road has shaped subsequent economic development.

We find that the historical presence of the Inca Road improved educational, development, and labour outcomes: it increased the average level of educational attainment by one year and decreased stunting among children by 5%. Over the long term, the existence of the Inca Road has boosted average hourly wages by 20% and reduced informality by six percentage points. Moreover, these effects are around 40% greater among women.

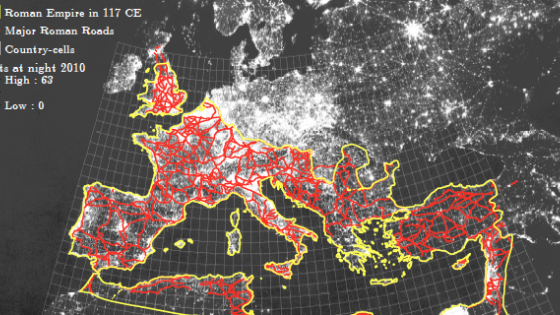

Our study contributes to the literature on ancient infrastructure’s long-run impact on economic development (Spolaore and Wacziarg 2013, Nunn 2014, and Ashraf and Galor 2018). This literature has largely been concerned with the impact of public goods provision over long periods of time. Dalgaard et al. (2019), for instance, explore the link between infrastructure investments made during antiquity and economic activity in Rome. They identify the emergence of market towns from the early medieval period to the modern era as a robust and economically meaningful mechanism that reflects the persistent effects of the Roman road network on economic activity.

Despite this vast body of literature, the role of pre-colonial forms of organisation has been explored less thoroughly and has mainly focused on African development (see Nunn 2008). For Latin America, no evidence on pre-colonial institutions has been gathered; however, based on the evidence for Africa, we strongly suspect that Latin American pre-colonial institutions account for a large part of the differences observed in current national and regional development processes. If this assumption proves to be correct, then it is a mistake to set the colonial period as the starting point for a study of development.

Finally, our paper also contributes to the literature regarding the persistence of gender roles shaped by historical cultural beliefs about the appropriate role of women (Alesina et al. 2013).

The Inca Road and development

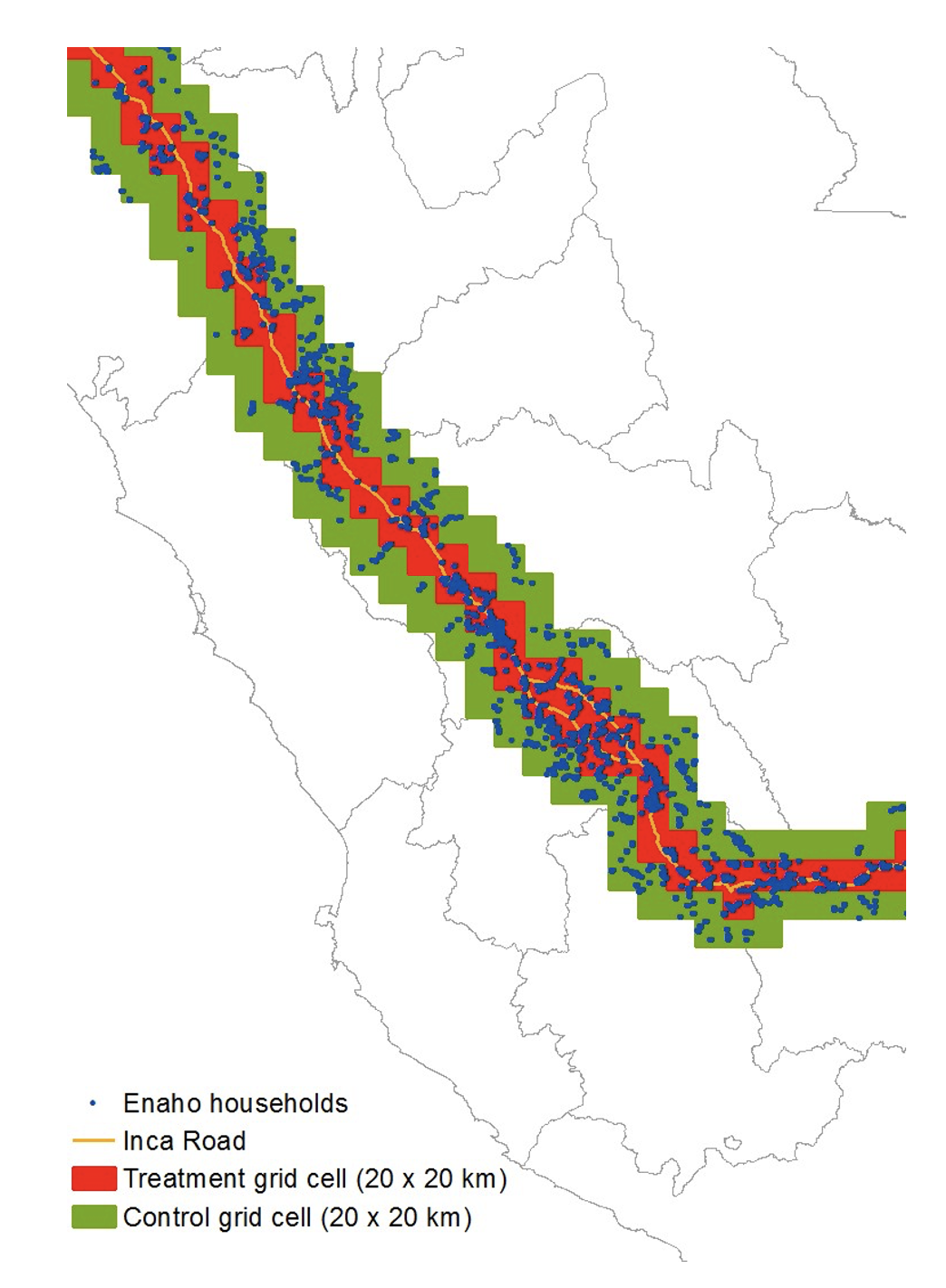

To estimate the long-term effect of the Inca Road, we test whether residence close to the Road has influenced today’s development outcomes. We construct a valid counterfactual for households classified as having been impacted by the Road in the spirit of Dell (2010). We do so by delimiting our study area to locations near the Inca Road that had similar relevant development characteristics before the road system was constructed.

Figure 1 shows our empirical strategy in graphic form. We define grid cells crossed by the Road as the treatment group (in red) and adjacent grid cells as the control group (in green). Households (in blue) that are located within the treatment grid cells form our sample of treated households and those located in the control grid cells, our control households.

Figure 1 Treatment and control groups in the proximity of the Inca Road

Results

We find a positive and statistically significant relationship between the Inca Road and hourly wages: residence within 20 km of the Inca Road increases hourly wages by around 10.5% as compared to wages in other areas during 2007–2017. This effect is as large as that of an additional year of schooling.

Along the same lines, we find a significant negative relationship between the Inca Road and child malnutrition: attendance at a school located within 20 km of the Inca Road reduced the probability of being malnourished by 3.4 percentage points (a reduction of around 8%) in 2005. In addition, we find a positive effect between the Inca Road and educational outcomes, with residence within 20 km of the Inca Road increasing the length of schooling by 1.64 years, which equals 22% of the average years of schooling of our sample (7.41 years).

With respect to the channels of persistence of the effects of the Inca Road, there is a significant and positive association between the Inca Road and the current provision of two main public goods, primary schools and roads. The 20-km grid cells crossed by the Inca Road have an extra 18 km of road density, which equals 82% of the road density in our sample. Similarly, we find that grid cells crossed by the Inca Road have an additional 48 primary schools, an increase of 79% over the sample average.

What is more, we find that there is a positive association between the Inca Road and current property rights, with the share of individuals holding property rights (ownership) to their land increasing by 31%.

Finally, we find a positive association between the Inca Road and female labour outcomes. Women who live within 20 km of the Inca Road average 1.63 more years of schooling than women who live farther from the road system. This is a sizeable increase (22%) over our sample mean (7.4 years), one which outpaces the increase for men.

There is also a positive association between the Inca Road and different measures of female intra-household bargaining power. Residence within 20 km of the Inca Road reduces the likelihood of being a teenage mother by 1.4 percentage points. It also increases the likelihood that women are making health-related decisions for the household by 5.2 percentage points and the likelihood that they are making decisions about high-value purchases, such as buying a home, by 5.4 percentage points.

References

Alesina, A, P Giuliano and N Nunn (2013), “On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128.

Ashraf, Q, and O Galor (2018), “The macrogenoeconomics of comparative development”, Journal of Economic Literature 56, 1119–55.

Dalgaard, C, N Kaarsen, O Olsson and P Selaya (2019), “Roman roads to prosperity: Persistence and non-persistence in public good provision”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12745.

Dell, M (2010), “The persistent effects of Peru’s mining mita”, Econometrica 78(6): 1863–903.

Franco, A, S Galiani and P Lavado (2021), “Long term effects of the Inca road”, NBER Working Paper 28979.

Glave, L M (1989), “Trajinantes. Caminos indígenas en la sociedad colonial siglos XVI/XVII”, Instituto de Apoyo Agrario.

Nunn, N (2008), “The long term effects of Africa’s slave trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(1): 139–76.

Spolaore, E, and R Wacziarg (2013), “How deep are the roots of economic development?”, Journal of Economic Literature 51: 325–69.