Macroprudential policy is still relatively new. While many emerging economies have been using macroprudential policy tools for some time (for a discussion of some of the benefits see Sandri et al. 2020), their use to safeguard financial stability was embraced more widely only in response to the global financial crisis.

The consensus is that financial sector reforms since the global financial crisis, including the use of macroprudential policy levers, helped the banking system to emerge resilient to the stresses from the COVID-19 crisis. However, the pandemic has also led to the build-up of new financial and economic vulnerabilities. A sharp increase in real estate prices may have contributed to rising debt levels in several countries. High inflation, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, is leading to a steep tightening of monetary policy, which may come to stress private sector balance sheets. These developments may pose new challenges to the conduct of macroprudential policy, underscoring the importance of a fuller understanding of its effects and its contribution to the overall policy mix to achieve macroeconomic stability.

Recognising that there still is much to learn, in our new paper (Biljanovska et al. 2023) we take stock of our expanding understanding of the effects and side effects of macroprudential measures. We draw from a meta-analysis of empirical research on the effects on credit and asset prices (Araujo et al. 2020) and newer research on the potential for resilience building and non-linear effects of macroprudential policy. We also present new analysis on the interaction of macroprudential policy with other policy levers, thereby differentiating our paper relative to other reviews (Galati and Moessner 2018, Forbes 2019, Araujo et al. 2020). The main takeaways are as follows.

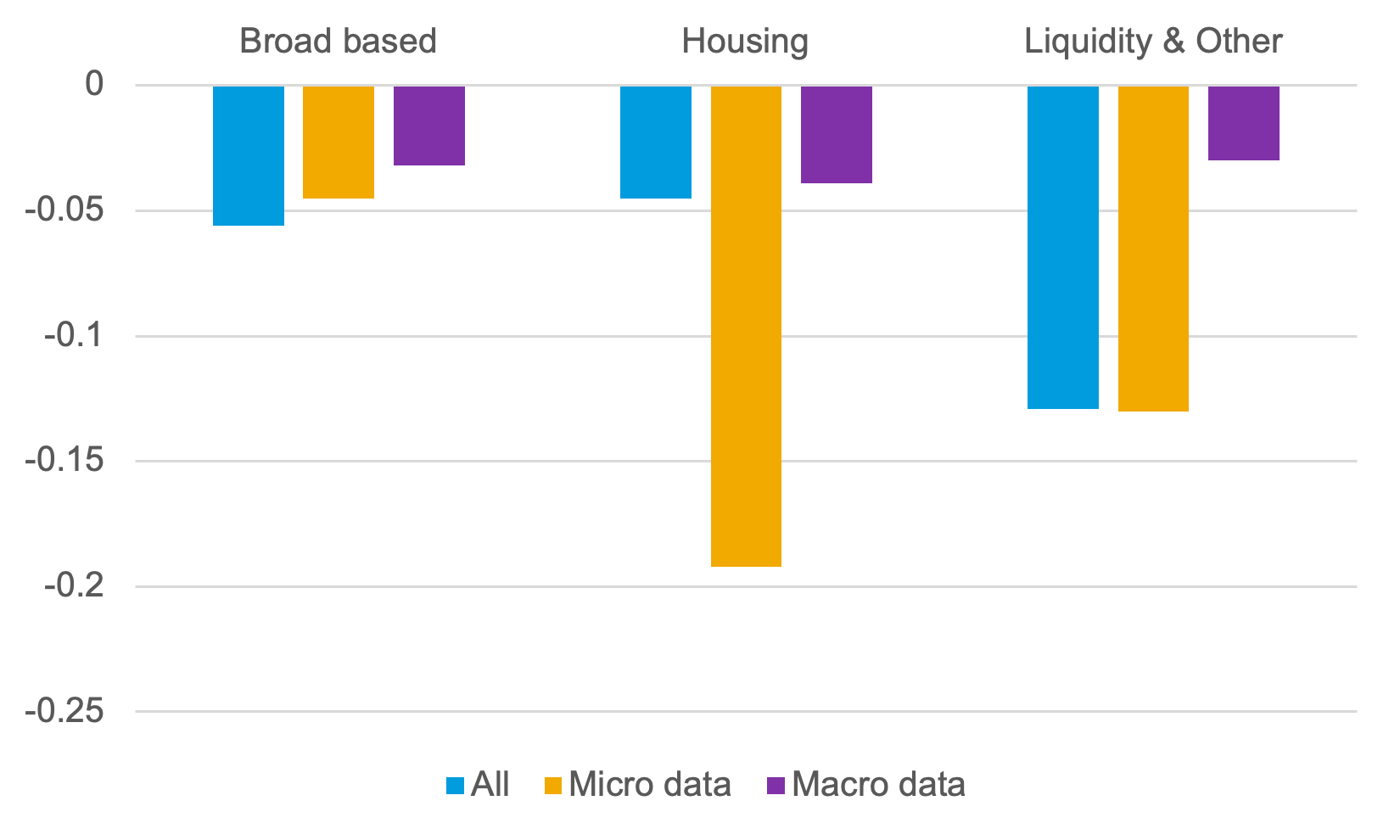

Macroprudential policies are effective in containing the growth of credit and residential real estate prices. Empirically, this is particularly evident when estimation takes account of the potential for endogenous policy responses. Relatively stronger effects from micro-level data and for sectoral and borrower-based tools (e.g. housing) underscore the usefulness of these tools in targeting specific vulnerabilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Average effects of tightening macroprudential tools

Note: This figure shows the average effects of tightening macroprudential measures on credit (including credit to households) obtained through weighted least squares regressions where the weights are proportional to the precision of each result. The dependent variable in such regressions is the coefficients collected by Araujo et al. (2020) from studies where the macroprudential policy is measured through -1,0,1 dummy variable at a horizon of up to one year, normalized by the standard deviation of the outcome variable. “All” depicts the average across the entire sample; “Micro” restricts the sample to studies where the unit of measurement is at the micro level (i.e., bank, firm, loan); and “Macro” restricts the sample to studies based on aggregate, macro-level data. All effects are statistically significant.

Source: Araujo et al. (2020)

The evidence also suggests that macroprudential policy can be used as a ‘surgical’ tool to limit specific vulnerabilities without major side effects on economic activity. In particular, the evidence points to small adverse effects on economic activity in the near term (see also Schularick et al. 2018). The evidence also suggests that macroprudential policy can strengthen the resilience of economies to external and domestic financial shocks, lowering risks of output contractions and volatility over the medium term.

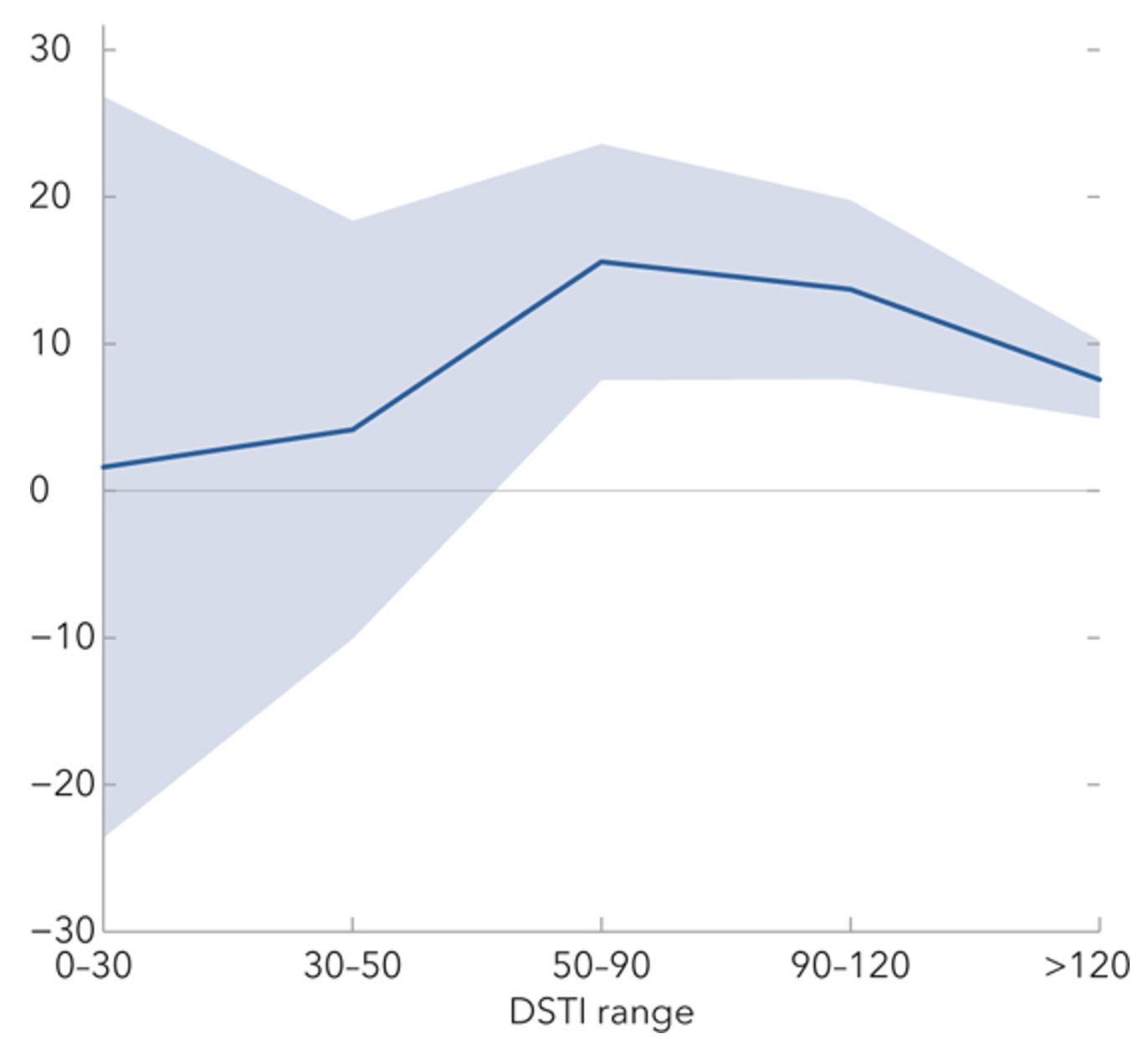

The emerging evidence also points to important asymmetries and nonlinearities that should be taken into account by policymakers. For instance, benefits – such as lower default probabilities – can be exhausted when tightening exceeds certain thresholds (Figure 2), pointing to diminishing marginal returns. Studies using granular data also find that effects on credit are weaker when tightening is more aggressive (e.g. Alter et al. 2019).

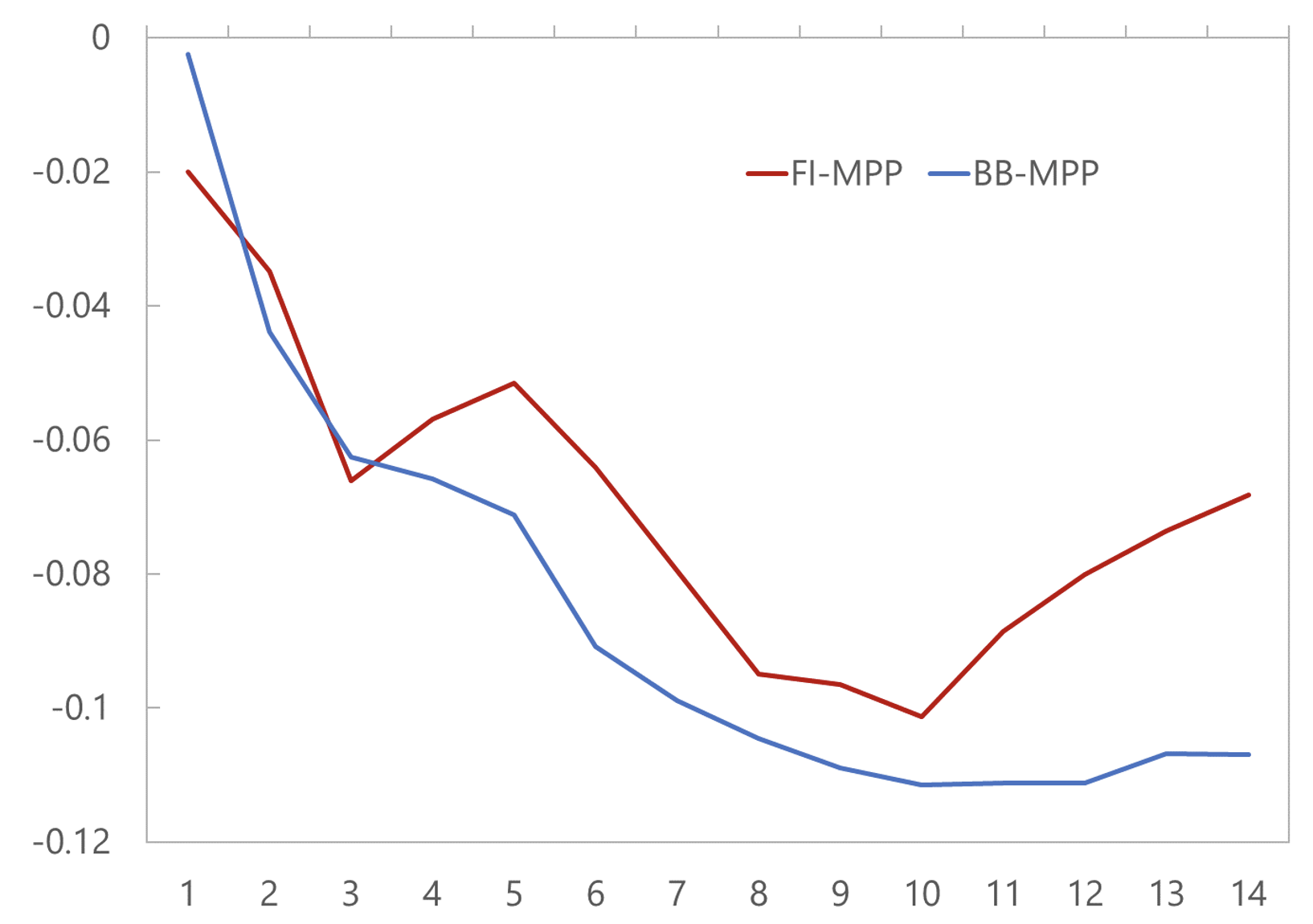

On average, stronger effects are found for tightening than for loosening measures, and during the buildup phase of the financial cycle. However, evidence from the COVID experience points to the value of macroprudential bank capital buffers that can be relaxed in periods of stress. And importantly, the resilience-building effects of macroprudential policy appear to persist rather than wane, and can even grow with time, especially for borrower based-tools (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Diminishing returns from macroprudential policies

Note: This figure plots the probability of default on mortgages for various levels of the debt service to income ratio (DSTI). The figures shows that the probability of default on a mortgage rises when the DSTI exceeds a threshold – estimated at 50 percent based on data from the Romanian credit registry.

Source: Nier et al.(2019).

Figure 3 Cumulative effect on loss function of the use of macroprudential tools

Note: The figure shows the cumulated change in the loss function when comparing a scenario of loose financial conditions without policy tightening to one where policy is tightened. BB-MPP = borrower-based macroprudential policy; FI-MPP = financial-institutions-based macroprudential policy. The horizontal axis shows the number of quarters since them time of the loosening shock of financial conditions and macroprudential tightening.

Source: Brandao-Marques et al. (2020).

Macroprudential tools are often circumvented. They are subject to domestic and cross-border leakages, with nonbanks and foreign lenders stepping in to provide credit. Effective regulation of non-banks is needed to complement macroprudential actions operating through the banking system. Similarly, effective capital flow management (CFM) measures, used in tandem with macroprudential measures, can help reduce cross-border leakages.

For emerging markets, there is evidence of complementarity with monetary policy and foreign exchange (FX) interventions, but this is not the case for advanced economies. In emerging markets, monetary policy, FX interventions, and macroprudential policies appear to have mutually reinforcing effects in moderating credit growth – particularly when credit growth is already high. By contrast, our evidence suggests a lack of such reinforcing effects in advanced economies.

Overall, we find that that there are strong benefits to using macroprudential policy tools to support financial stability. This should encourage more countries to make active use of the toolkit. Our paper also highlights the need for further research and guidance to better support policymakers in their use of macroprudential policies. Additional research is needed on the role of macroprudential policy in strengthening the resilience of the financial system and the interaction of macroprudential measures with other policies. Further analysis on macroprudential policy actions that uses granular data on the size of policy steps could help quantify the linear and non-linear effects of different tools more precisely and allow policymakers to improve their calibration.

Finally, most of the evidence reviewed in our paper focuses on macroprudential measures imposed on banks and their borrowers. Looking forward, new frontiers of macroprudential policy lie in containing systemic risks stemming from nonbank financial intermediation, as well as from crypto assets and digital money.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management

References

Alter, A, G Gelos, H Kang, M Narita, and E Nier (2019), “Unveiling the Effects of Macroprudential Policies,” VoxEU.org, 3 April.

Araujo, J, M Patnam, A Popescu, F Valencia, and W Yao (2020), “Effects of Macroprudential Policy: Evidence from over 6,000 Estimates”, IMF Working Paper 20/67.

Biljanovska, N, S Chen, G Gelos, D O Igan, M S Martinez Peria, E Nier, and F Valencia (2023), "Macroprudential Policy Effects: Evidence and Open Questions”, IMF Departmental Paper 23/002.

Brandao-Marques, L, G Gelos, M Narita, and E Nier. 2020. “Leaning Against the Wind: An Empirical Cost-Benefit Analysis”, IMF Working Paper 20/123.

Forbes, K J (2019), “Macroprudential Policy: What We’ve Learned, Don’t Know, and Need to Do”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 109: 470–75.

Galati, G, and R Moessner (2018), “What Do We Know About the Effects Of Macroprudential Policy?”, Economica 85: 735–70.

Nier, E, R Popa, M Shamloo, and L Voinea (2019), “Debt Service and Default: Calibrating Macroprudential Policy Using Micro Data”, IMF Working Paper 19/182.

Sandri, D, F Grigoli, N-J Hansen and K Bergant (2020), “Macroprudential Regulation can Effectively Dampen Global Financial Shocks”, VoxEU.org, 12 August.

Schularick, M, I Shim, and B Richter (2018), “The costs of macroprudential policy”, VoxEU.org, 21 September.