Recent electoral outcomes such as the election of Donald Trump in 2016 or the Brexit vote that same year surprised many of us. Many viewed these outcomes as ‘wrong’ in the sense that information was not aggregated correctly. In particular, factually incorrect beliefs about many aspects of these elections persisted and determined these aggregate choices. A suspect culprit for the misinformation that led to such choices has been the new media, often accused of being biased and partisan, a debate that is ongoing.

The media landscape has changed drastically over the past several years. Mainstream cable news used to be the dominant news provider, but in the current environment, people can choose to consume news from a plethora of possible media sources – ranging from print media to YouTube channels. The richness of new media has perhaps benefited people by allowing them to tailor their media choices to their wants. However, the incredible diversity of viewpoints on offer, combined with new technologies, has made it easier for citizens to become insulated from possibly contrary perspectives offered, for instance, by traditional media outlets. Several papers have looked at the effects of echo chambers and the electoral consequences of unawareness of being in echo chambers (e.g. Levy and Razin 2015, Ortoleva and Snowberg 2015).

Metejka and Tabellini (2020, 2021) also show that the variety of media sources available allows people to divert attention away from important but non-controversial issues towards more extreme policy dimensions, thus amplifying their influence.

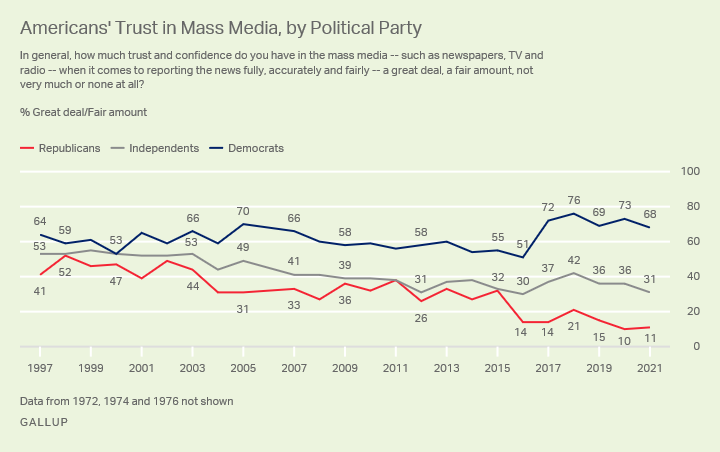

While the media landscape has become much richer, trust in traditional media has declined markedly over the past two decades. Especially in the past five years, this media distrust has followed radically different paths on either side of the political spectrum in the US. As we can see below, the gap in media trust between Republicans and Democrats is staggering and widened during the Trump presidency – possibly due to the former president's well-documented disparaging of the mainstream media.

Figure 1 Asymmetry in trust in mass media

Indeed, as noted by the Pew Foundation in Jurkowitz et al. (2020), “one of the clearest differences between Americans on opposing sides the political aisle is that large portions of Democrats express trust in a far greater number of news sources.”

The influence of the above-mentioned phenomena on aggregate electoral outcomes is compounded, especially in the US, by the presence of a very polarised landscape in which traditional ideological, religious, and racial identities are being replaced by overlapping meta-identities captured almost entirely by the Democratic and Republican political faiths. Citizens have become less responsive to new information or real national problems, as if political affiliations determine what information people absorb, rather than the other way around (e.g. Mason 2018). Furthermore, Kahan (2017) finds that people exhibit motivated reasoning to protect political identity, while Kaanders et al. (2022) note that individuals search for information to preserve their beliefs.

Relatedly, Guriev et al. (2019, 2021) show how the internet has led to increased support for both left-wing and right-wing populist movements by reducing the cost of reaching voters.

These three phenomena — the emergence of a dense array of media outlets, partisan distrust of media, and motivated choice of media by citizens — have repercussions for how political beliefs are formed and updated, and thus for people’s decisions on election day. But can this new information environment generate aggregate beliefs biased enough to swing an election? Further, can it provide a rationale behind the fomenting of distrust in mainstream media observed during the Trump presidency?

Identity-based preferences

Taking heed of the above issues, our recent paper (Herrera and Sethi 2022) explores the link between political identities, media choices, and electoral outcomes.

We assume that each citizen identifies with a party, on the left or the right, and aims to protect their political identity. They choose media to maximise the likelihood that after their beliefs are rationally updated, they believe their party is the better match for the state of the world. Such beliefs are based on just two signals: an ‘Inside’ signal and an ‘Outside’ signal. The Inside signal is generated from a structure that represents the collection of media outlets an agent chooses. The Outside signal comes from outlets an agent is inadvertently exposed to – the nature of this signal will depend on the nature of mainstream media at large. In other words, citizens choose media attempting to shield themselves from possibly unfavourable (from the point of view of their political affiliation) outside news to which they are somewhat exposed.

Equivalently, one can think of agents as having two selves – a heart and a mind. The heart chooses Inside media while the mind votes sincerely. The objective of the heart is to persuade the mind to vote for the heart’s preferred party. In either interpretation, citizens are fully rational in the way they process all information they receive and update their beliefs based on the two signals and vote according to their posterior for the better candidate.

The election aggregates all votes, each based on two conditionally independent signals of which of two candidates is preferable. The key behavioural assumption of our model regards not information processing but the preference that drives each citizen’s choice of ‘In-media’, i.e. the tailored media outlets, each of which we view as a particular known signal structure.

Asymmetry in exposure to outside news

Citizens that distrust the mainstream media may choose to avoid exposure to it. Thus, an asymmetric distrust of mainstream media could imply an asymmetry in exposure. The nature of media that agents choose to consume (‘In-media’) is influenced by their beliefs regarding the mainstream (‘Outside’) media. A difference in media choice has surprising implications for electoral outcomes.

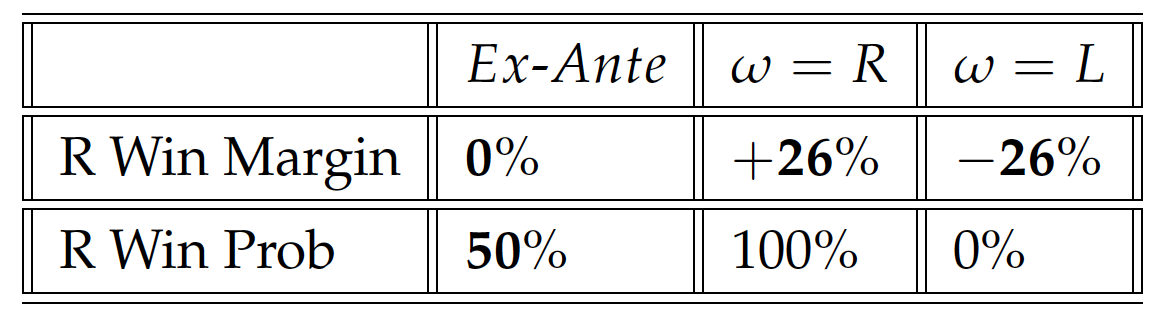

In the example below, we study the size of the electoral advantage (winning margin) of the side less exposed to mainstream media assuming that each citizen votes for the party she rationally beliefs to be superior. We assume that citizens of either type (left- or right- affiliated) are symmetric in all respects other than exposure. Specifically, there is a large and equal number of partisans of each type, ‘L’ and ‘R’. Also, there are two equally likely states of the world, ω = L, R, denoting which of two candidates is the better one.

To highlight the implications of rich media landscape made possible by the proliferation of new media, we first consider electoral outcomes in the absence of Inside media and compare that with outcomes in which citizens choose their Inside media.

We conceptualise asymmetric exposure by supposing that type-L citizens receive i.i.d. symmetric binary signals from mainstream news with precision 0.75, while type-R citizens receive noisier i.i.d. mainstream signals, namely with a lower precision of 0.51. The winning margin and winning probability for the R side depend solely on the realisations of the Outside signal and are summarised in the table below:

Thus, asymmetric exposure to mainstream media generates symmetric electoral outcomes. In this baseline case, the ideal/correct candidate is always elected, i.e. information is perfectly aggregated. No personal media choice is made by citizens, and thus political faith, or the type of citizen, plays no role.

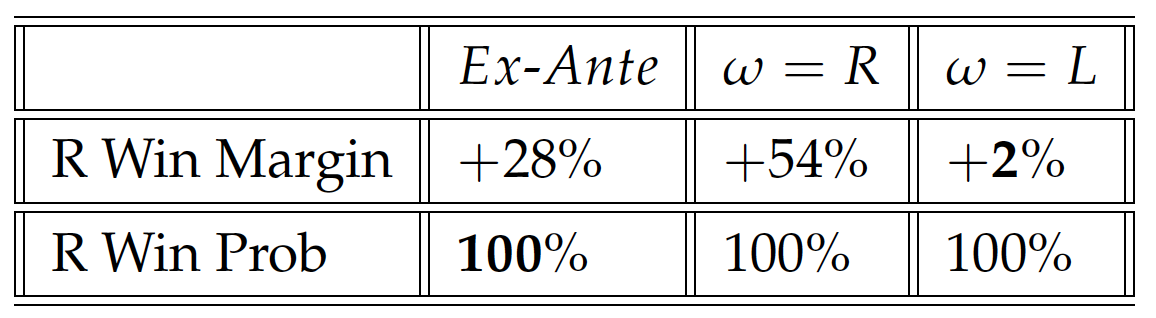

Now, suppose instead that citizens can also curate Inside media sources optimally. Here, their voting decision is made after updating rationally on two signals, not one. If each agent chooses media to maximise the chance of political faith preservation, then the outcome of the election is no longer symmetric. In fact, it may be drastically skewed. In this example, the winning margin and winning probability for the R side are:

In this case, the R side has an ex-ante winning margin advantage in the election. Surprisingly, it also has an advantage ex-post. Namely, the R side wins the election in either state of the world in this case and information is not aggregated, despite agents voting based solely on (rational updating of) the information they received.

Mechanism

The surprising result above is driven by the fact that citizens on either political side choose qualitatively different media. Less-exposed citizens (the right in our example) contend with a far less informative Outside signal, which implies that they maximise the likelihood of preserving their political faith by choosing a one-sided signal structure, for which news favourable to one candidate is very frequent and thus not so informative, while unfavourable news is rare and hence damning. This is perhaps reminiscent of partisan outlets like Fox News or Breitbart News for Republicans. On the other hand, to contend with the more informative Outside signal, more-exposed citizens (the left in our example) optimally choose more balanced news.

Importantly, in a world without a rich set of signal structures (In-media) available to agents to select from, even if partisan biases that drive media choice were present, we would not see the stark bias in aggregate electoral outcomes in the example above.

Additionally, we find that an asymmetry in distrust of the mainstream media by partisan citizens can lead to a substantial electoral advantage for the less trusting side. The mechanism that generates this advantage remains that distrusting citizens largely disregard an unfavourable Outside signal, which induces them to choose more biased Inside media, which preserves their political faith with a greater likelihood even in the incorrect state of the world. This may be one reason we have observed party elites disparage the mainstream media.

If citizens on the two sides also have heterogeneous priors biased towards their side, then the scope for the failure of information aggregation expands. Results are qualitatively unchanged if we assume that each citizen votes for her culturally affiliated party only if she believes it is better, and abstains otherwise, namely if we assume turnout/abstention margins determine electoral outcomes. In this case, all winning margins would simply be halved. The results are also robust to agents placing utility on holding posteriors more favourable to their side, or a small amount of utility on voting for the correct party.

References

Benkler, Y, R Faris, H Roberts and E Zuckerman (2017), “Study: Breitbart-led right-wing media ecosystem altered broader media agenda”, Columbia Journalism Review.

DellaVigna, S and E Kaplan (2007), “The Fox News effect: Media bias and voting”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3): 1187–1234.

Guriev, S, N Melnikov and E Zhuravskaya (2019), “Knowledge is power: Mobile internet, government confidence, and populism”, VoxEU.org, 31 October.

Guriev, S, N Melnikov and E Zhuravskaya (2021), “3g internet and confidence in government”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(4): 2533-2613.

Herrera, H and R Sethi (2022), “Identity-Based Elections”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17203.

Jurkowitz, M, A Mitchell, E Shearer and M Walker (2020), “U.S. media polarization and the 2020 election: A nation divided”, Pew Research Center.

Kaanders, P, P Sepulveda, T Folke, P Ortoleva and B De Martino (2022), “Humans actively sample evidence to support prior beliefs”, Elife 11: e71768.

Kahan, Dan M (2017), “Misconceptions, Misinformation, and the Logic of Identity-Protective Cognition”, Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 575.

Levy, G and R Razin (2015), “Correlation neglect, voting behavior, and information aggregation”, American Economic Review 105(4): 1634–45.

Mason, L (2018), Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity, University of Chicago Press.

Matějka, F and G Tabellini (2020), “Political information in the age of the internet”, VoxEU.org, 10 January.

Matějka, F and G Tabellini (2021), “Electoral competition with rationally inattentive voters”, Journal of the European Economic Association 19(3): 1899-1935.

Ortoleva, P and E Snowberg (2015), “Overconfidence in political behavior”, American Economic Review 105(2): 504–35.