Macroprudential policy has helped better assess and address systemic risks within the financial system in a way that complements microprudential policy’s mitigation of individual institutions’ risks. Before the global financial crisis, “few supervisors, if any, could see the wood for all the trees and nor did they see that the woods were connected across borders” (Ingves 2021). Macroprudential policy has since then been operationalised in the EU through the ESRB (ESRB 2011, 2014b). The ESRB has helped significantly improve our understanding and analysis of sources of systemic risk within the financial system as a whole, ranging from the real estate sector (e.g. ESRB 2022b) to the insurance sector and investment funds. It has helped improve the quality and availability of supervisory data (e.g. ESRB 2016b) and supported the implementation of European-wide stress testing of the banking sector. Furthermore, it has been at the forefront of developing analysis of new financial risks related to climate change and cyber risk, for example proposing, as early as 2016, that climate risk stress tests be implemented (ESRB 2016a).

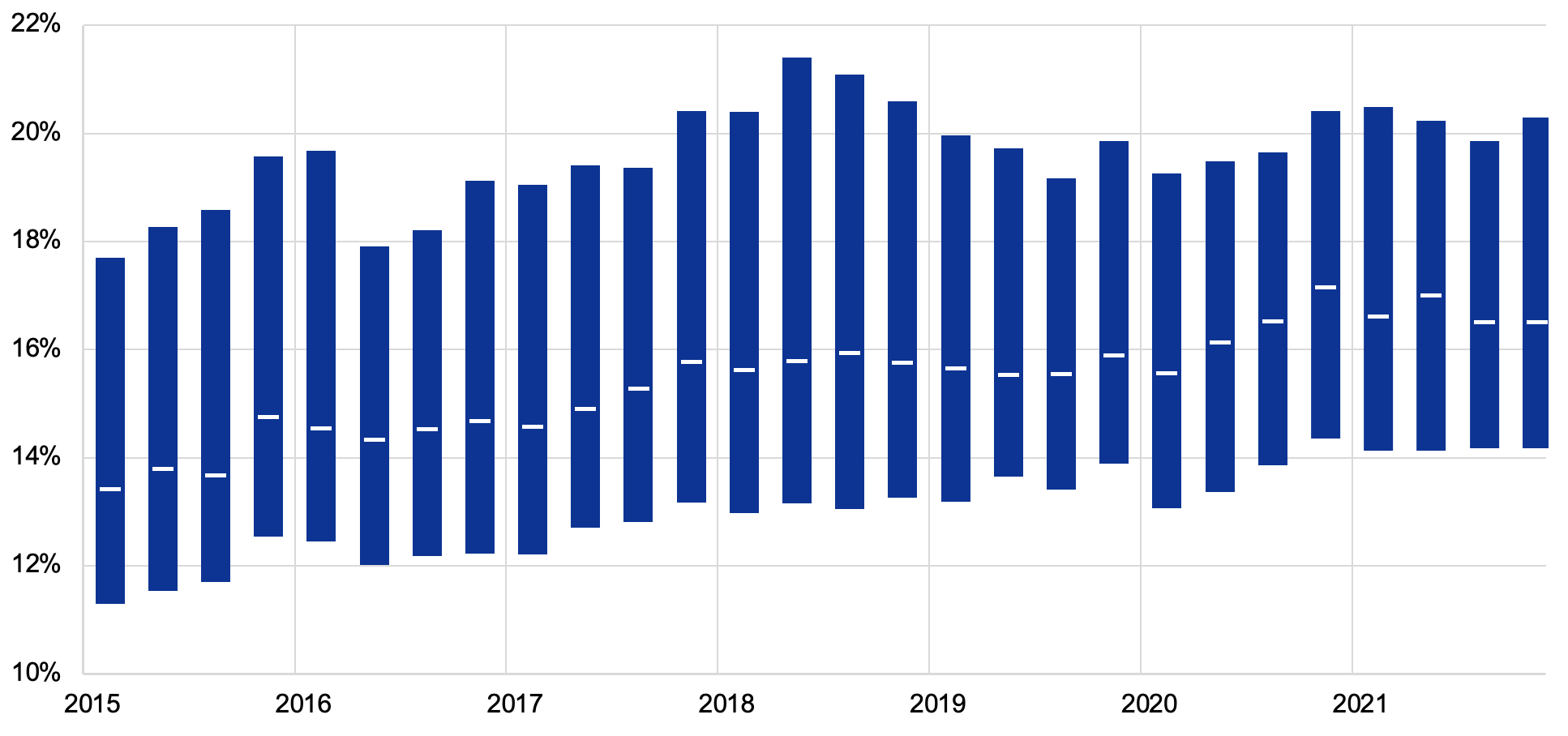

Since 2014, the EU Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation has provided a macroprudential toolkit, enabling authorities to address both cyclical and structural systemic risks (ESRB 2014a). Microprudential reforms improved the resilience of EU banks through higher capital requirements, better quality of capital and higher liquidity buffers. The implementation of complementary macroprudential tools has further enhanced the resilience of the EU banking sector against systemic risks. For example, systemically important banks must hold additional capital, thus helping to address the too-big-to-fail problem (FSB 2021). Due to the combined micro- and macroprudential capital requirements, banks’ median ratio of Common Equity Tier 1, i.e. ‘hard capital’, to risk-weighted assets increased from around 13% at the beginning of 2014 to 17% in mid-2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Common Equity Tier 1/risk-weighted assets ratio of banks in the EU

(percentages, interquartile range and median, latest observation Q4 2021)

Source: ESRB Risk Dashboard (2022).

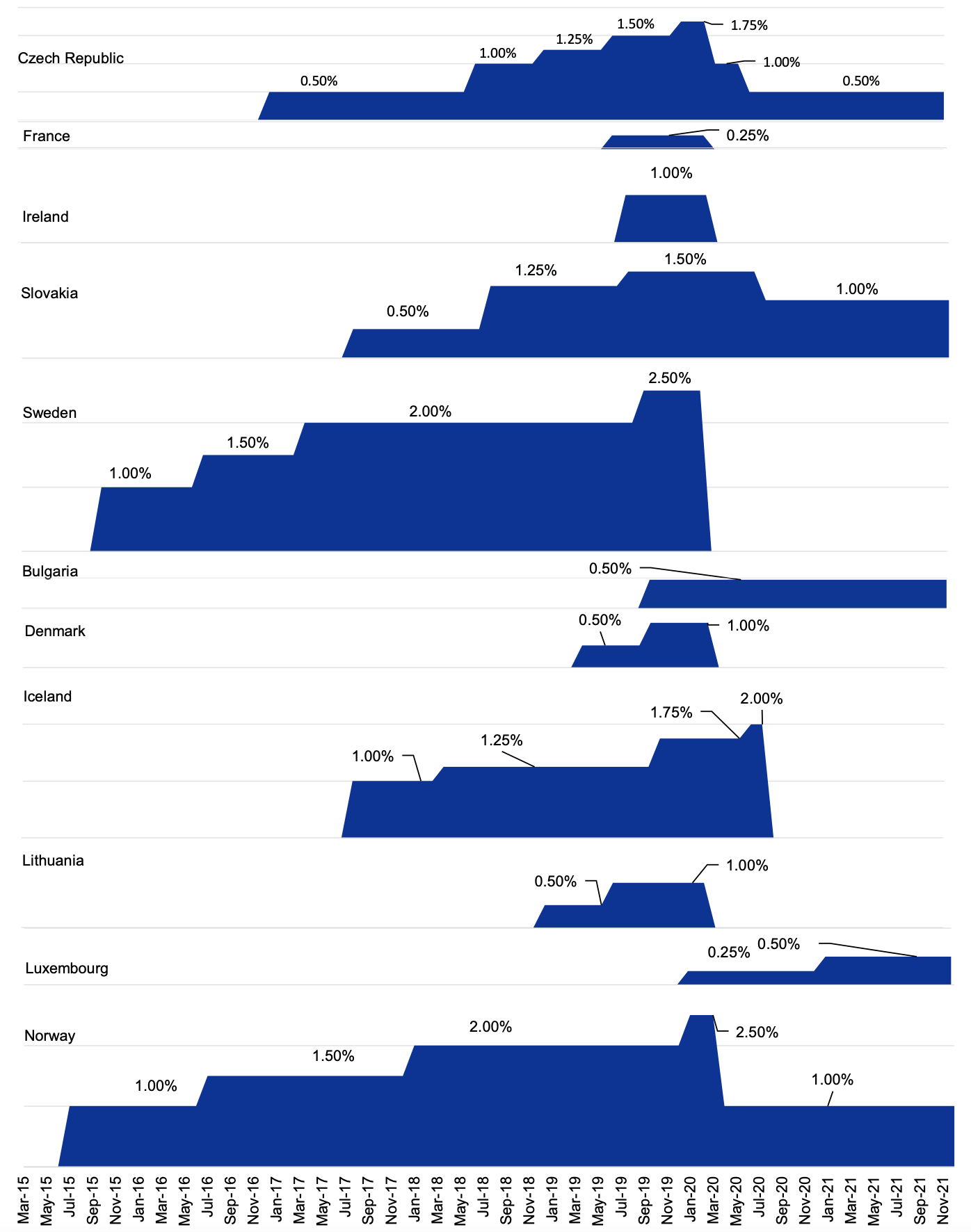

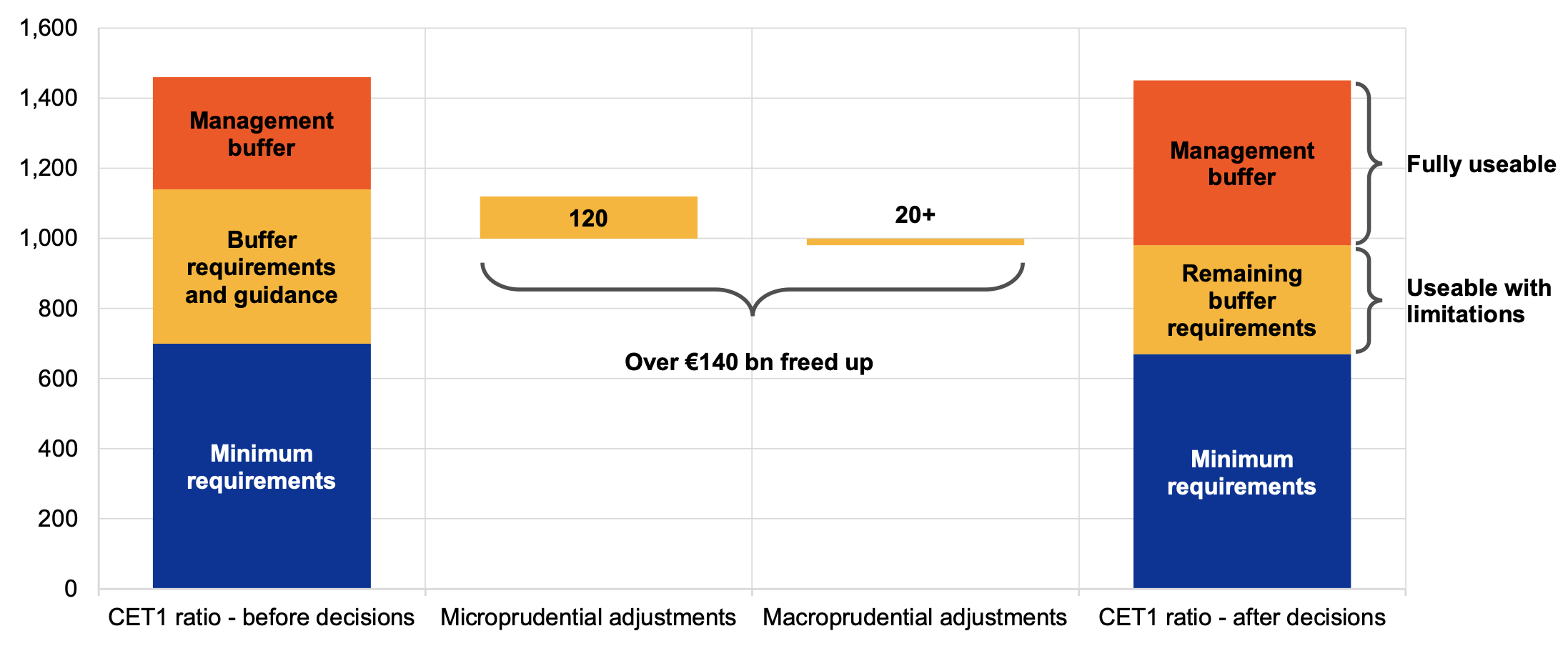

The various regulatory changes of the past decade contributed to banks’ resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. Those EU countries which had built up releasable buffers such as the countercyclical capital buffer used them for macroprudential loosening in response to the COVID-19 shock (Figure 2). Overall, empirical evidence suggests that capital relief measures were effective in supporting credit supply during the pandemic (ECB 2021). However, while microprudential adjustments freed up €120 billion in the euro area, only €20 billion was freed up by macroprudential measures (Figure 3).

More macroprudential space at the beginning of the crisis would therefore have allowed a release of more macroprudential capital during the crisis. Yet, future crises might be different as the financial system is evolving, therefore both current limitations and future challenges need to be taken into account in order to enhance the macroprudential framework.

Figure 2 Member States with a positive countercyclical capital buffer rate before the COVID-19 pandemic

(Countercyclical capital buffer rate, latest observation December 2021)

Source: ESRB.

Note: Countries not shown had not built up a positive countercyclical capital buffer before the COVID-19 crisis struck.

Figure 3 In comparison to microprudential adjustments, macroprudential adjustments freed up only a fraction of overall Common Equity Tier 1 capital in the euro area in response to the COVID-19 shock

(EUR billions, latest observation Q4 2019)

Source: “Macroprudential Policy Issues”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2020.

Notes: The sample covers significant and less significant institutions, consolidated at the euro area level. Microprudential adjustments include the decision on regulatory adjustment to the Pillar 2 Requirements and making the guidance temporarily usable. Macroprudential adjustments include the releases of the countercyclical capital buffer, the systemic risk buffer, and the other systemically important institutions buffer.

How to enhance the macroprudential framework

The ESRB has developed a comprehensive set of proposals to enhance the EU macroprudential framework. The proposals are part of the ESRB’s response to the European Commission’s call for advice on the 2022 review of the macroprudential framework for the banking sector (ESRB 2022c, 2022d). The ESRB is advocating for a banking macroprudential policy framework that (i) allows policy makers to act in a forward-looking manner to foster resilience before systemic risks materialise; (ii) can be adapted to structural changes in the financial system, as well as to risks related to cyber and climate change; and (iii) forms part of a holistic framework, that promotes congruent regulation across all activities in the financial system and facilitates cooperation between authorities at all levels. An overarching aim of the reform is also to reduce the complexity of legal provisions, both procedurally and conceptually: this would facilitate their use by authorities without weakening existing safeguards.

More releasable capital can be obtained through an earlier and more forward-looking build-up of the countercyclical capital buffer. This could be combined with a positive neutral rate, i.e. a rate set to a positive amount in a standard, non-elevated risk environment. An increase of releasable capital should however not happen at the expense of non-releasable capital. It is therefore important to keep the capital conservation buffer at 2.5% to preserve sufficient capital for potential future loss absorbency.

Increasing macroprudential space through higher releasable capital buffers would not only improve resilience but also improve buffer usability. ESRB analysis has shown that for several banks, dipping into the buffers would result in a breach of the parallel minimum requirements for the leverage ratio or minimum requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities (ESRB 2021b).

A higher amount of macroprudential space, which is the sum of releasable and non-releasable capital buffers, would be one way to improve buffer usability.

Risk weights also play a crucial role in determining the amount of capital that banks must hold to foster their resilience against different sources of risk and as such they should also include a systemic risk component. The disparate legal provisions on risk weights (spread across Articles 124, 164, and 458 of the Capital Requirements Regulation) should be replaced with a new single harmonised macroprudential article.

The EU macroprudential framework should be enriched with a basic set of borrower-based measures for residential real estate loans. Evidence shows that one of the main causes of past banking and financial crises has been credit-driven real estate “boom-and-bust” cycles (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009a). Recessions following residential real estate busts tend to be particularly deep and prolonged, with severe repercussions in terms of consumption, investment, and employment. Borrower-based measures, such as limits on loan-to-value or debt-to-income, can help mitigate these risks by ensuring minimum credit standards for new housing loans and so should be at the disposal of all EU countries. At the same time, national specificities need to be respected: decisions on the activation and release of borrower-based measures, as well as the calibration and the overall application of the measures, should be left in the hands of national authorities.

A congruent regulation should apply similar requirements to all entities carrying out the same type of financial activities, complementing entity-based with activity-based regulation (ESRB 2019, Metrick and Tarullo 2021). As borrower-based measures could be extended to all borrowers, independent of the institutional entity of the lender, the inclusion of borrower-based measures, for example in the Mortgage Credit Directive and the Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation could thus help prevent regulatory arbitrage (ESRB 2022e).

Given their potential to disrupt critical financial services and operations, cyber incidents pose a systemic risk to the financial system and may impair key economic functions. The macroprudential mandate therefore needs to be expanded to encompass cyber resilience (ESRB 2022a). It should include critical third-party service providers of information and communication technology as already foreseen for microprudential supervision in the Digital Operational Resilience Act proposal.

Moreover, additional cyber resilience requirements for systemically important institutions should be introduced (IMF 2019).

The systemic nature of climate-related financial risks is widely acknowledged (NGFS 2019, ESRB 2020, FSB 2020). The ESRB, together with the ECB, is assessing how macroprudential policy could provide options for addressing the system-wide aspects of climate-related financial risks – both transition and physical risks (ESRB 2021a, 2022f). Existing tools such as the systemic risk buffer and large exposure limits could be relevant to address the systemic aspects of climate risk. As a growing body of analysis becomes available, further adjustments and possible new tools, such as concentration charges, should also be considered.

Policymaking for the banking and financial sector overall would benefit from even deeper coordination and simpler procedures. Enhancing cooperation, coordination, and data-exchange between micro- and macroprudential authorities, resolution authorities and central banks is key.

Conclusion

Financial stability is an essential foundation on which to build the EU of the future (European Commission 2021). It allows the financial system to serve European households and businesses, and thus contributes to sustainable economic growth across the EU. In light of recent experience and of future challenges, this is the right time to enhance the macroprudential toolkit and to make the macroprudential framework fit for the next decade.

References

Beck, T, F Mazzaferro, R Portes, J Quin and C Schett (2020), “Preserving capital in the financial sector to weather the storm”, VoxEU.org, 23 June.

ECB (2021), “Bank capital buffers and lending in the euro area during the pandemic”, ECB Financial Stability Review.

ESRB (2011), “Recommendation on the macroprudential mandate of national authorities”, ESRB.

ESRB (2014a), Flagship Report on Macroprudential Policy in the Banking Sector, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2014b), Handbook on operationalising macroprudential policy in the banking sector.

ESRB (2016a), Too late, too sudden: Transition to a low-carbon economy and systemic risk, ESRB Advisory Scientific Committee Report 6.

ESRB (2016b), “Recommendation of the European Systemic risk Board on closing data gaps”, ESRB.

ESRB (2019), Regulatory complexity and the quest for robust regulation, ESRB Advisory Scientific Committee Report 8.

ESRB (2020), Positively green: Measuring climate change risks to financial stability, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2021a), Climate-related risk and financial stability, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2021b), Report of the Analytical Task Force on the overlap between capital buffers and minimum requirements, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2022a), Mitigating systemic cyber risk, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2022b), Vulnerabilities in the residential real estate sectors of the EEA countries, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2022c), “Review of the EU macroprudential framework for the banking sector – A Concept Note”, ESRB Report.

ESRB (2022d), “Review of the EU macroprudential framework for the banking sector – Response to the call for advice”, ESRB Response.

ESRB (2022e), “ESRB response to EU Commission consultation of the review of the mortgage credit directive”, ESRB Response.

ESRB (2022f), The macroprudential challenge of climate change, ESRB Report.

European Commission (2021), The EU’s capacity and freedom to act, European Commission Strategic Foresight Report.

FSB (2020), “The implications of climate change for financial stability”, Financial Stability Board.

FSB (2021), "Evaluation of the effect of too-big-to-fail reforms", Financial Stability Board.

IMF (2019), “Cybersecurity Risk Supervision”, IMF Departmental Paper.

Ingves, S (2021), “A decade of macroprudential policy”, Fifth ESRB Annual Conference, opening remarks.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2008), “Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database”, IMF Working Paper.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2010), “Resolution of Banking Crises: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly”, IMF Working Paper.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2013), “Systemic Banking Crises Database”, IMF Economic Review 61(2): 225-270.

Metrick, A and D K Tarullo (2021), “Congruent financial regulation”, Brookings.

NGFS (2019), A call for action Climate change as a source of financial risk, Network for Greening the Financial System report.

Reinhart, C and K Rogoff (2009a), “The Aftermath of Financial Crises”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper.

Reinhart, C and K Rogoff (2009b), This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton University Press.