In April 2011, as part of a long-term shift toward transparency, then Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke started holding press conferences on the final day of some Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings. These press conferences have since become a highly anticipated part of the Fed’s communications with the public. Recent events highlight just how large the impact of FOMC press conferences can be on markets: during six FOMC press conferences in the past year, the S&P 500 lost or gained over 1% – $300 billion – in value.

A large literature considers how Fed communications affect financial markets (as surveyed by Blinder et al. 2008, and with recent contributions by Hansen and McMahon 2016, Nakamura and Steinsson 2018, Bauer and Swanson 2022, and Byrne et al. 2023). In a recent paper (Narain and Sangani 2023), we build on this literature by documenting two new facts about the market impact of FOMC press conferences.

First, market volatility is higher during FOMC press conferences than at other times. This has been true since 2011 but is especially the case for press conferences given by current Fed Chair Jerome Powell, suggesting that press conferences have played an outsized role in shaping recent market expectations. Second, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the press conference tended to reinforce the FOMC statement, with markets moving in the same direction during the press conference as they did when initially reacting to the statement. However, since the start of the pandemic, stock and bond markets have tended to move in the opposite direction during press conferences compared to their initial reaction to the FOMC statement. This reversal in direction is systematically linked to the words used in Chair Powell’s speeches. In this column, we discuss these patterns and what they mean for Fed communications going forward.

Heightened market volatility during recent conferences

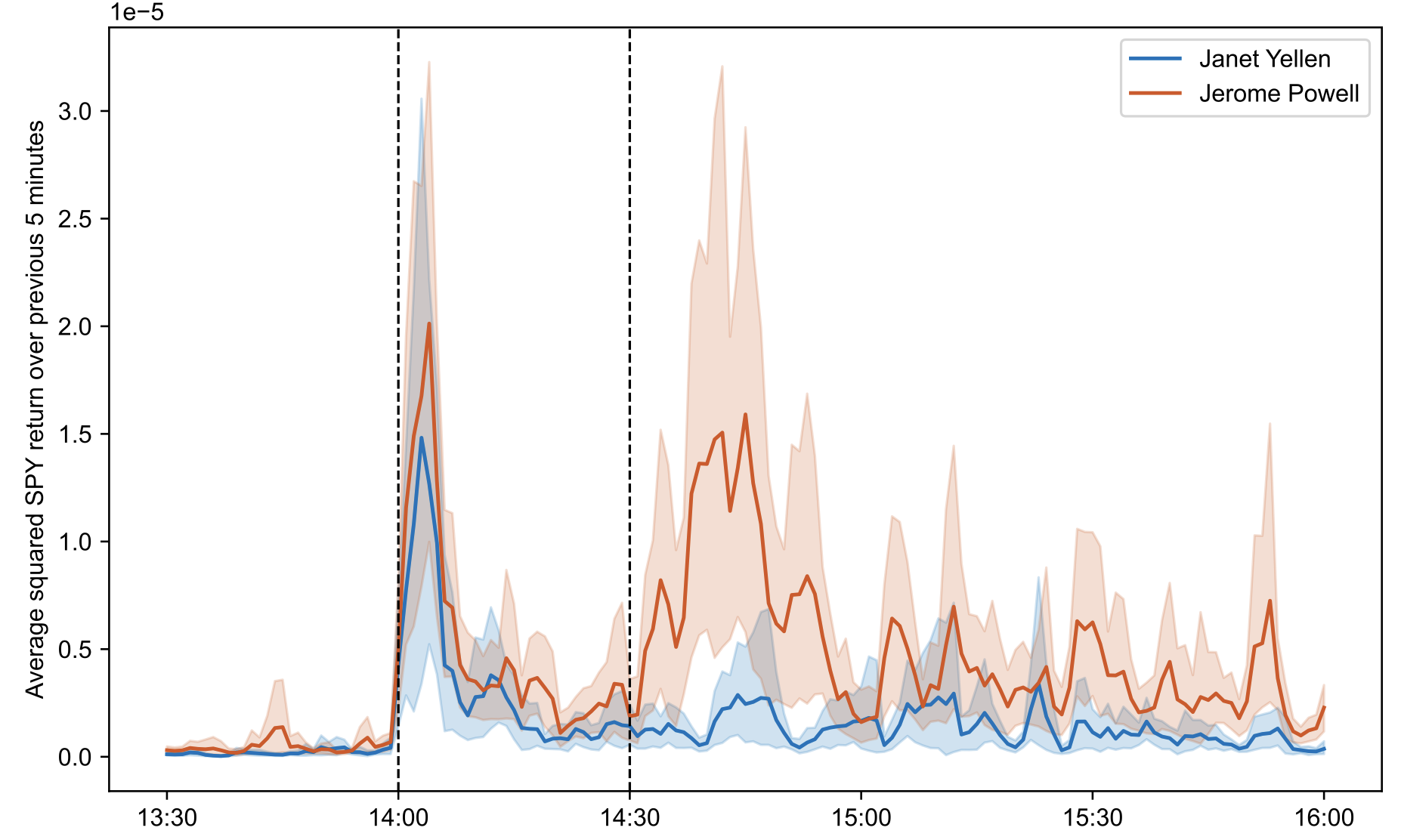

As discussed by Rosa (2013), realised market volatility can serve as an indicator for the release of market-relevant information. Figure 1 plots the volatility of S&P 500 returns on the days of press conferences given by Chair Powell and his predecessor, Janet Yellen. As documented by previous work (Gürkaynak et al. 2004, Rosa 2013), the release of the FOMC statement at 2:00 p.m. is marked by a sharp increase in volatility as markets react to new information in the statement. The start of the press conference at 2:30 p.m. is accompanied by another rise in volatility, particularly for recent conferences under Chair Powell’s tenure.

Figure 1 Market volatility on FOMC press conference days

Note: The figure shows average squared returns of the S&P 500 index (proxied by the SPY ETF) over five-minute periods from 1:30 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. on FOMC press conference days. Dashed lines indicate the FOMC statement release time (2:00 p.m.) and the press conference start time (2:30 p.m.). Each line plots the average of squared returns for the previous five minutes across all press conferences given by the chair. The shaded area is a bootstrapped 95% confidence interval. We do not include Chair Bernanke in this figure, since the timing of statement releases and press conferences varied during his tenure.

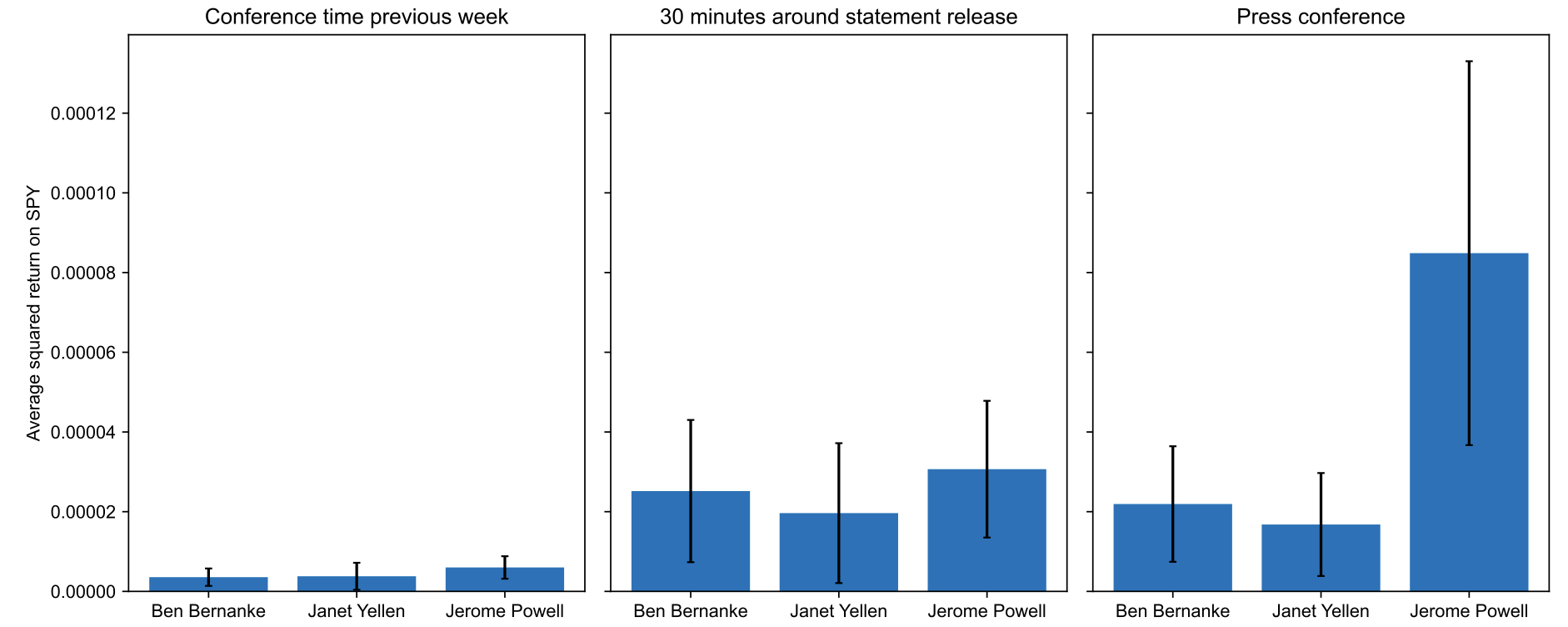

The elevated market volatility during Fed press conferences is summarised in Figure 2, which measures the volatility of market returns during the press conference, around the FOMC statement release, and during a ‘placebo conference’ (i.e. the same time as the press conference, but a week prior) across the three previous chairs. Though market volatility is heightened during the press conferences held by all three chairs, it is especially pronounced during Chair Powell’s tenure: market volatility during his press conferences is three times greater than under previous chairs.

Figure 2 Market volatility for placebo conference, FOMC statement release, and press conference

Note: The figure shows the average squared returns of the S&P 500 index (proxied by the SPY ETF) over press conferences given by Chair Powell, Chair Yellen, and Chair Bernanke. We measure returns from the minute before the press conference starts to the minute it ends. For comparison, we show average squared returns during the conference time the previous week and for the 30-minute window around the FOMC statement release. We exclude emergency and unscheduled conferences: the 4 March 2014 unscheduled conference call under Chair Yellen and the emergency COVID-19 related press conferences given by Chair Powell on 3 March 2020 and 15 March 2020.

One explanation for the heightened market volatility during Chair Powell’s conferences could be the more volatile macro environment under his tenure, which includes the pandemic response and subsequent resurgence of inflation. However, there is no significant difference in market volatility across the three chairs during the placebo window, suggesting the heightened volatility during Chair Powell’s press conferences is not an artifact of higher baseline market volatility.

Moreover, there is no significant difference across chairs in market volatility in the minutes following the FOMC statement release, suggesting that heightened volatility during Chair Powell’s press conferences is not the result of more surprising interest rate policy. We consider several alternate measures of the market volatility associated with press conferences in our paper. Across these measures, we find evidence of heightened market volatility for Chair Powell’s conferences since the onset of COVID-19, with null or small differences in volatility for the release of the FOMC statement or other Fed-related news.

Reversals

What is the nature of the information released at the FOMC press conference? When the practice was instituted in 2011, its stated intention was to “enhance the clarity and timeliness of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy communication”. In practice, this meant sticking close to the FOMC statement with few elaborations. As one commentator said after Chair Bernanke’s first conference in 2011: “Basically, Mr. Bernanke made no mistakes, added little to what we know but did show, at least to the public, that he understands their concerns” (Arnall 2011).

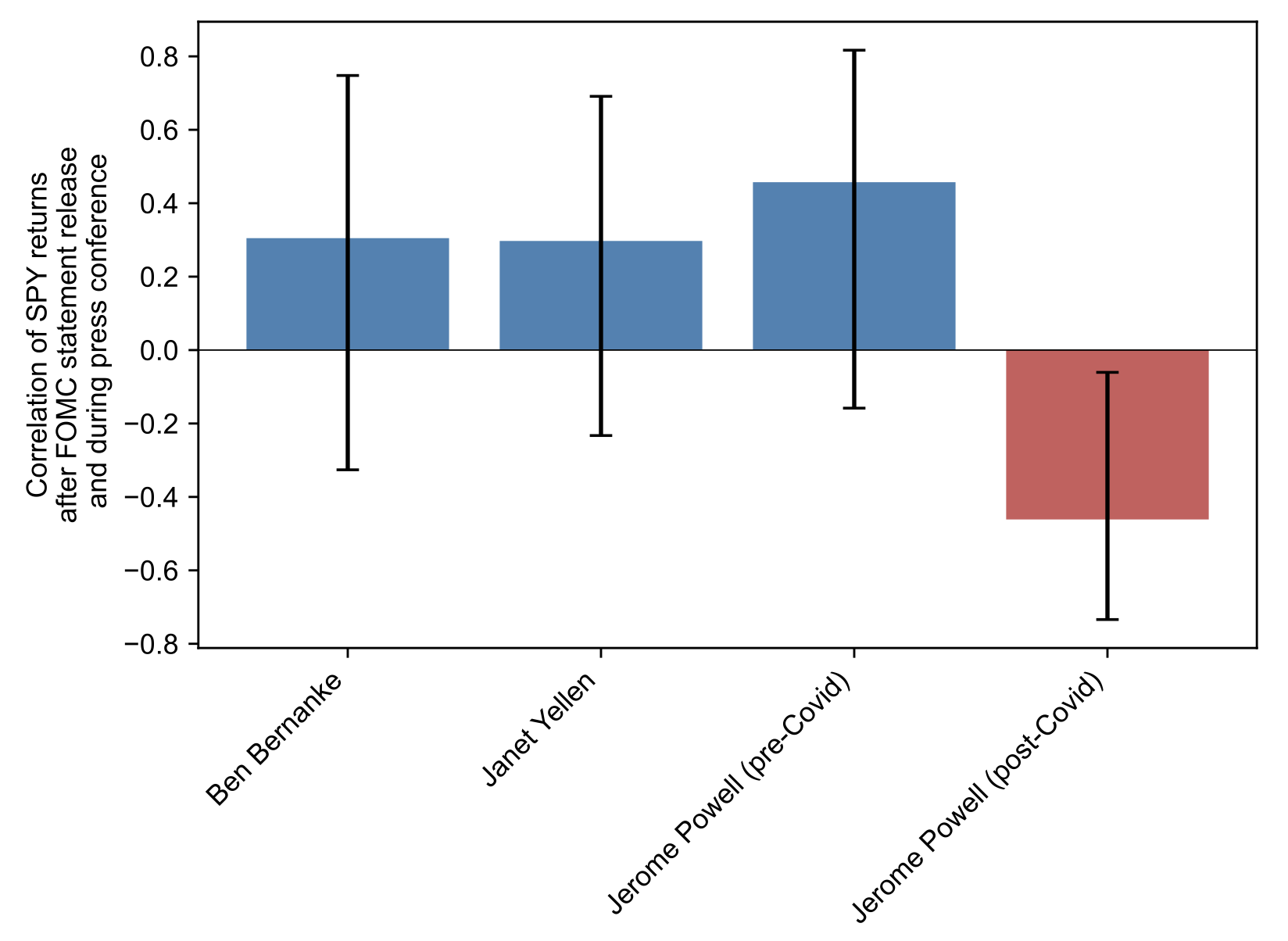

Under Chairs Bernanke and Yellen, the Fed press conference typically reaffirmed the message delivered in the FOMC statement. Figure 3 shows that markets tended to move the same direction during the press conference as they initially moved after the FOMC statement release under their tenures (as previously documented by Gómez-Cram and Grotteria 2022). While this was true of Chair Powell’s pre-Covid conferences, recent conferences have departed from the pattern. Since March 2020, markets have tended to move in the opposite direction during Chair Powell’s conferences than they initially moved following the FOMC statement release.

Figure 3 Correlation of market reaction to FOMC statement release with market reaction to press conference

Note: Correlation of S&P 500 returns after statement release and during press conference for each chair. A positive correlation means that the S&P 500 tended to move in the same direction after the statement release and during the press conference given by the chair. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

One explanation for these market reversals is that the market has been over-reactive to recent FOMC statements as it “leans in to hear better” (in the words of Stein 2014). Overreaction is a common feature of financial markets and will tend to generate reversals as beliefs correct (Bordalo et al. 2020). By analysing the text of the Q&A during Chair Powell’s recent press conferences, however, we link the market movements during recent press conferences to language used by Chair Powell, rather than solely latent overreaction in markets. For example, we find that Chair Powell used language that tends to be associated with positive stock market reactions to FOMC statements in his press conference on 21 September 2022, during which markets rallied and two-year Treasury yields fell nearly eight basis points. He shifted to significantly more negative language during his 2 November 2022 conference, during which equity markets fell nearly 2%.

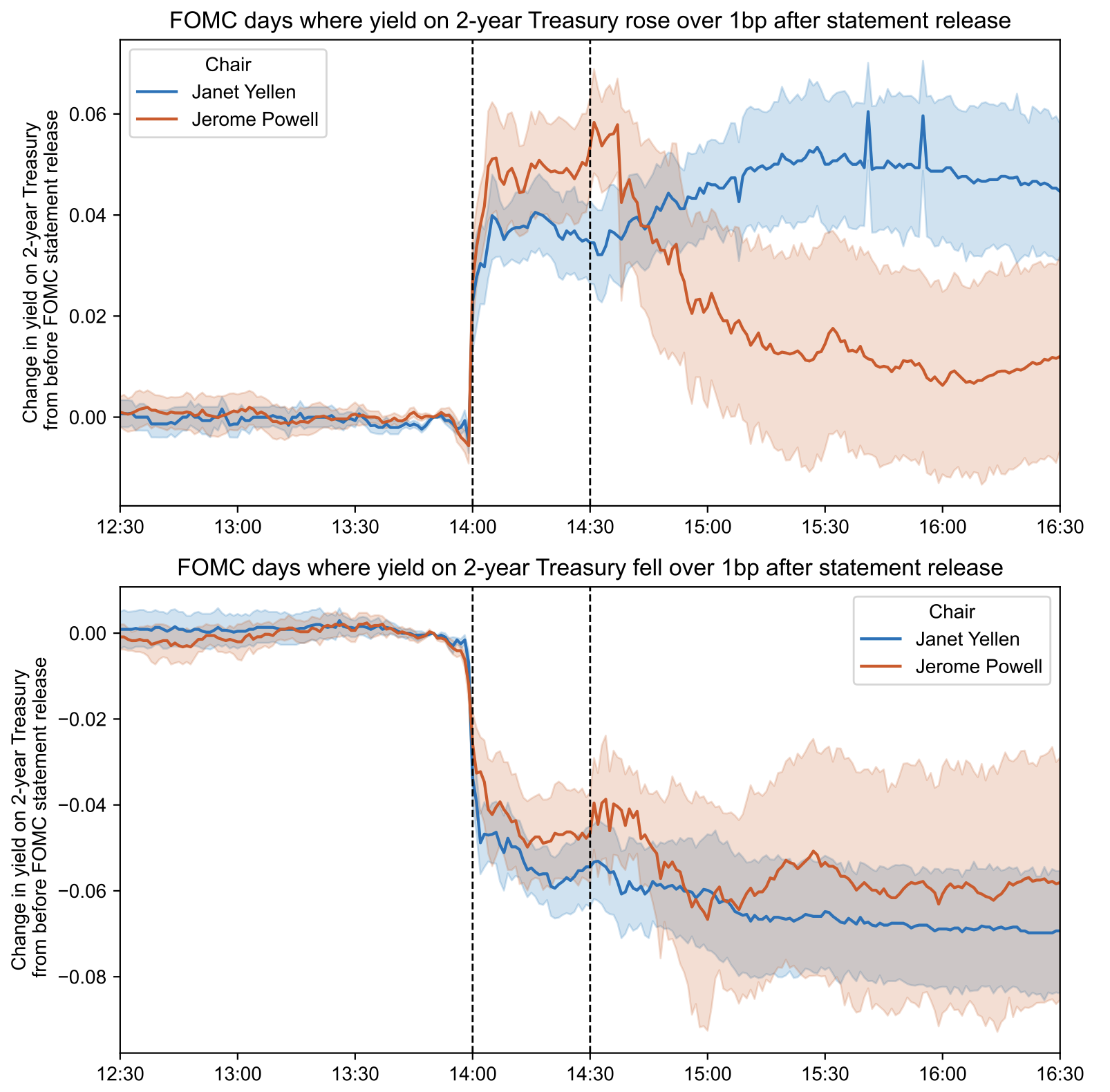

These market reversals suggest the FOMC statement is no longer the ‘last word’ on interest rate guidance from the Fed. Take the path of two-year Treasury yields over FOMC press conference days under Chairs Yellen and Powell in Figure 4. Under Chair Yellen’s tenure, bond markets reacted swiftly to the FOMC statement release and tended to stick around that level following the press conference. However, under Chair Powell’s tenure – particularly on days when the FOMC statement release led to an increase in Treasury yields – the initial market reaction to the FOMC statement release is partially reversed during the press conference.

Figure 4 Path of two-year Treasury yields on FOMC press conference days, split by conference where two-year yields increased/decreased more than one basis point following FOMC statement release

Note: The figure shows the average change in the yield of two-year Treasuries relative to 1:50 p.m. on the day of the FOMC press conference. Dashed lines indicate the FOMC statement release time (2:00 p.m.) and the press conference start time (2:30 p.m.). See Narain and Sangani (2023) for the list of conferences under Chairs Yellen and Powell included in each panel. The shaded area is a bootstrapped standard error (68% confidence interval).

Conclusion

These patterns indicate a shift in the role of the Fed press conference to one of growing importance – and not always as a straightforward reiteration of the FOMC statement. Such changes may be due course for a communication strategy that is always evolving: Chair Powell also doubled the number of press conferences held per year compared to his predecessors, and the FOMC statement has seen shifts in length, complexity, and diversity of viewpoints shared over time (e.g. Acosta and Meade 2015, Josselyn and Meade 2017). It is also possible that the press conference allows the Chair to emphasise his own views and get out ahead of other committee members – Meade (2005) and Gerlach-Kristen and Meade (2010) document strategies used by previous chairs to manage dissent – or to broach parts of the FOMC discussion not captured by the FOMC statement that the market finds consequential.

On the other hand, deviating from the unified message in the FOMC statement and causing increased market volatility may be at odds with the Fed’s other communication goals. As explained by Alan Blinder (1998), “By making itself more predictable to the markets, the central bank makes market reactions to monetary policy more predictable to itself. And that makes it possible to do a better job of managing the economy”. Large fluctuations in stock and bond markets certainly seem incompatible with the goals of increasing predictability and reducing uncertainty. Indeed, we show evidence that recent conferences have been less successful at reducing uncertainty about the path of future interest rates, as measured using implied volatility of options on short- and long-term Treasuries.

A final possibility is that the goal of minimising market fluctuations is the wrong one. As Stein (2014) posits, a Fed that has “developed a reputation for worrying less about the immediate bond-market effect of its actions [...may] be able to adjust policy more nimbly when it needed to”. In other words, when the FOMC is learning about the state of the economy at as rapid a clip as today, perhaps a Fed Chair willing to jostle markets is exactly what is needed.

References

Arnall, D (2011), "The Federal Reserve announced today a key interest rate will remain the same", ABC News, 27 April.

Acosta, M and E E Meade (2015), Hanging on every word: Semantic analysis of the FOMC’s post- meeting statement, Technical Report 2015-09-30, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Bauer, M D, A Lakdawala and P Mueller (2022), “Market-based monetary policy uncertainty”, The Economic Journal 132(644), 1290–1308.

Bauer, M D and E T Swanson (2022), “A reassessment of monetary policy surprises and high-frequency identification”, NBER Macroeconomic Annual.

Blinder, A S (1998), Central Banking in Theory and Practice, MIT Press.

Blinder, A S, M Ehrmann, M Fratzscher, J D Haan and D J Jansen (2008), “Central bank communication and monetary policy: A survey of theory and evidence”, Journal of Economic Literature 46(4): 910–945.

Bordalo, P, N Gennaioli, R LaPorta and A Shleifer (2020), “Belief overreaction and stock market puzzles”, NBER Working Paper no. 27283.

Byrne, D, R Goodhead, M McMahon and C Parle (2023), “The central bank crystal ball: Temporal information in monetary policy communication”, VoxEU.org, 16 March.

Cremers, M, M Fleckenstein and P Gandhi (2021), “Treasury yield implied volatility and real activity”, Journal of Financial Economics 140(2): 412–435.

Gerlach-Kristen, P and E E Meade (2010), “Is there a limit on FOMC dissents? Evidence from the Greenspan era”, American University Working Paper.

Gómez-Cram, R and M Grotteria (2022), “Real-time price discovery via verbal communication: Method and application to Fedspeak”, Journal of Financial Economics 143(3): 993–1025.

Gürkaynak, R S, B P Sack and E T Swanson (2005), “Do actions speak louder than words? The response of asset prices to monetary policy actions and statements”, International Journal of Central Banking 1(1): 55–93.

Hansen, S and M McMahon (2016), “Shocking language: Understanding the macroeconomic effects of central bank communication”, Journal of International Economics 99, 114–133.

Josselyn, M and E E Meade (2017), “The FOMC meeting minutes: An update on counting words”, Technical Report 2017-08-03, FEDS Notes.

Kwon, S Y and J Tang (2020), “Extreme events and overreaction to news”, Technical Report 3724420, SSRN.

Meade, E E (2005), “The FOMC: preferences, voting, and consensus”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 87.

Nakamura, E and J Steinsson (2018), “High-frequency identification of monetary non-neutrality: the information effect”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(3): 1283–1330.

Narain, N and K Sangani (2023), “The Market Impact of Fed Communications: The Role of the Press Conference”, working paper.

Rosa, C (2013), “The financial market effect of FOMC minutes”, FRBNY Economic Policy Review.

Sinha, A (2015), “FOMC forward guidance and investor beliefs”, American Economic Review 105(5): 656–661.

Stein, J C (2014), “Challenges for monetary policy communication: Remarks at the Money Marketeers of New York University”, 6 May.