With the rise of online ‘gig’ platforms in recent years, policy debates over how to regulate independent contracting have intensified. Critics charge that businesses use platform workers and other independent contractors to avoid the legal liabilities and costs associated with employees, pushing workers into insecure, low-paid jobs without protections such as minimum wages and unemployment insurance. Proponents argue that these arrangements are a ‘win-win’ for workers and businesses – helping workers bridge spells of unemployment, choose their own schedules, and build their own businesses, while providing businesses with a flexible workforce.

In the US, state and federal policymakers are drafting and implementing new laws and rules to change who may be classified as an independent contractor (Telford 2022, Smith 2023). Unfortunately, these policy debates and regulatory actions are occurring in a vacuum of information about how many independent contractors there are and the characteristics of these workers, let alone the consequences of these arrangements for workers’ wellbeing. Existing data from household surveys and tax records provide an incomplete and inconsistent picture (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020, Abraham and Houseman 2022).

In our research (Abraham et al. 2023), we investigate reasons that standard household surveys may fail to count many independent contractors and show how surveys can measure independent contracting work more accurately. Based on focus groups and new survey data, our findings upend the traditional picture of contract work. Our data suggest that traditional survey questions fail to identify nearly half of the independent contractor workforce and that those who have been missed are disproportionately workers in disadvantaged groups.

Designing better survey questions to capture independent contracting

Independent contracting takes many forms: freelance consultants provide technical services to businesses; drivers provide rideshare services through platforms like Uber and Lyft; and informal workers provide home maintenance, child care, and elder care services. As self-employed workers, independent contractors in the US are not covered by wage and hours laws, do not have the right to unionise, and are not eligible for workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance, or most employer-provided benefits.

An accurate picture of the size and composition of the independent contractor workforce is essential for policymaking that aims to improve workers’ wellbeing, but it has proved hard to come by. In the US, the key source of government survey data on these arrangements is the Contingent Worker Supplement to the Current Population Survey, which was fielded six times between 1995 and 2017.

Estimates based on the Contingent Worker Supplement consistently suggest that about 6–7% of workers are independent contractors on their main job and that they are disproportionately white and higher paid (Abraham and Houseman 2020). Other surveys that ask more probing questions and collect information about work arrangements on all jobs, not just the main job, suggest higher levels of self-employment or independent contractor work, as do tax records.

To better understand why independent contractor work may not be well captured in many surveys, including the Contingent Worker Supplement, we began our research by conducting focus groups with independent contractors. We sought to learn how they think and speak about their work, and what their answers suggest about how they would respond to typical survey questions regarding work arrangements.

Our focus groups showed that independent contractors typically described themselves as ‘working for’ their clients, especially when they worked for only one or a few organisations or via an online platform. Even though these workers knew that they were legally self-employed, many surveys would likely miscode them as employees. This is because most surveys code individuals who report working for an organisation as employees and do not allow for the possibility that they work for the organisation on a contract basis.

We used these findings to design and implement a large, telephone-based survey that probed about workers’ job arrangements. We partnered with Gallup to field the module in 2018–19 to about 61,000 adults, making it the largest household survey other than the Contingent Worker Supplement to investigate contract work.

Traditional surveys may miss many independent contractors

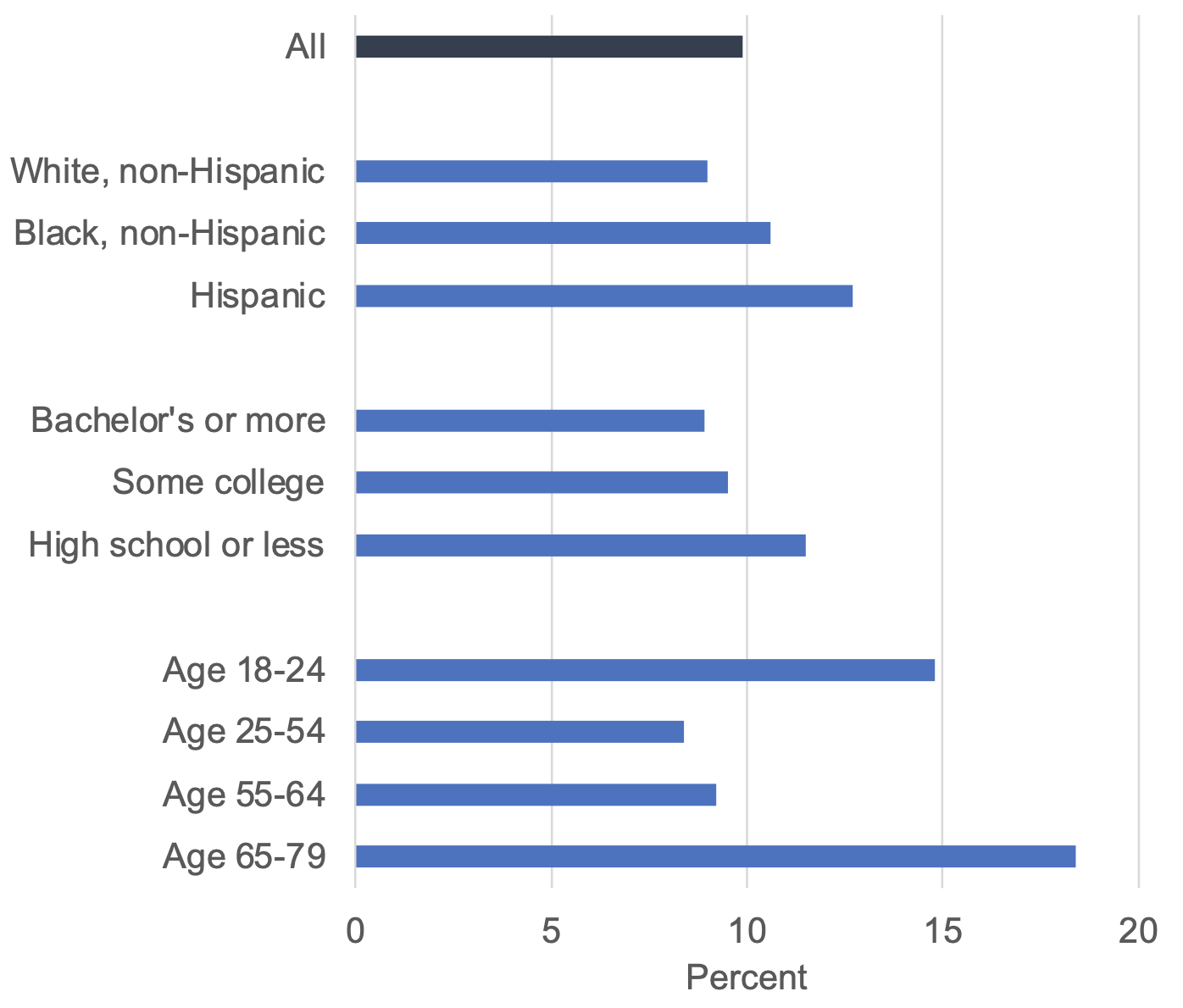

By asking follow-up questions about contract work, we found that about one in ten people who initially said they worked for an employer on one or more jobs were actually independent contractors on at least one of those jobs (Figure 1). Black and Hispanic workers, workers with less formal education, and workers under age 24 or over age 65 were especially likely to be miscoded.

Figure 1 Nearly one in ten workers ‘employed by an employer’ on one or more jobs is actually an independent contractor on at least one of those jobs

Notes: Estimates are the share of those ‘employed by an employer’ on any job who, when asked a probing question, indicate that they are an independent contractor on at least one job. See Abraham et al. (2023) for details. Source: Authors’ tabulations of Gallup Contract Work module data.

Adjusting for this miscoding transforms the common picture of independent contracting. Focusing on the main job so that our estimates are more comparable to those from the Contingent Worker Supplement, we found that, after adjustment, the share of workers who were counted as independent contractors nearly doubled to 15% from 8%.

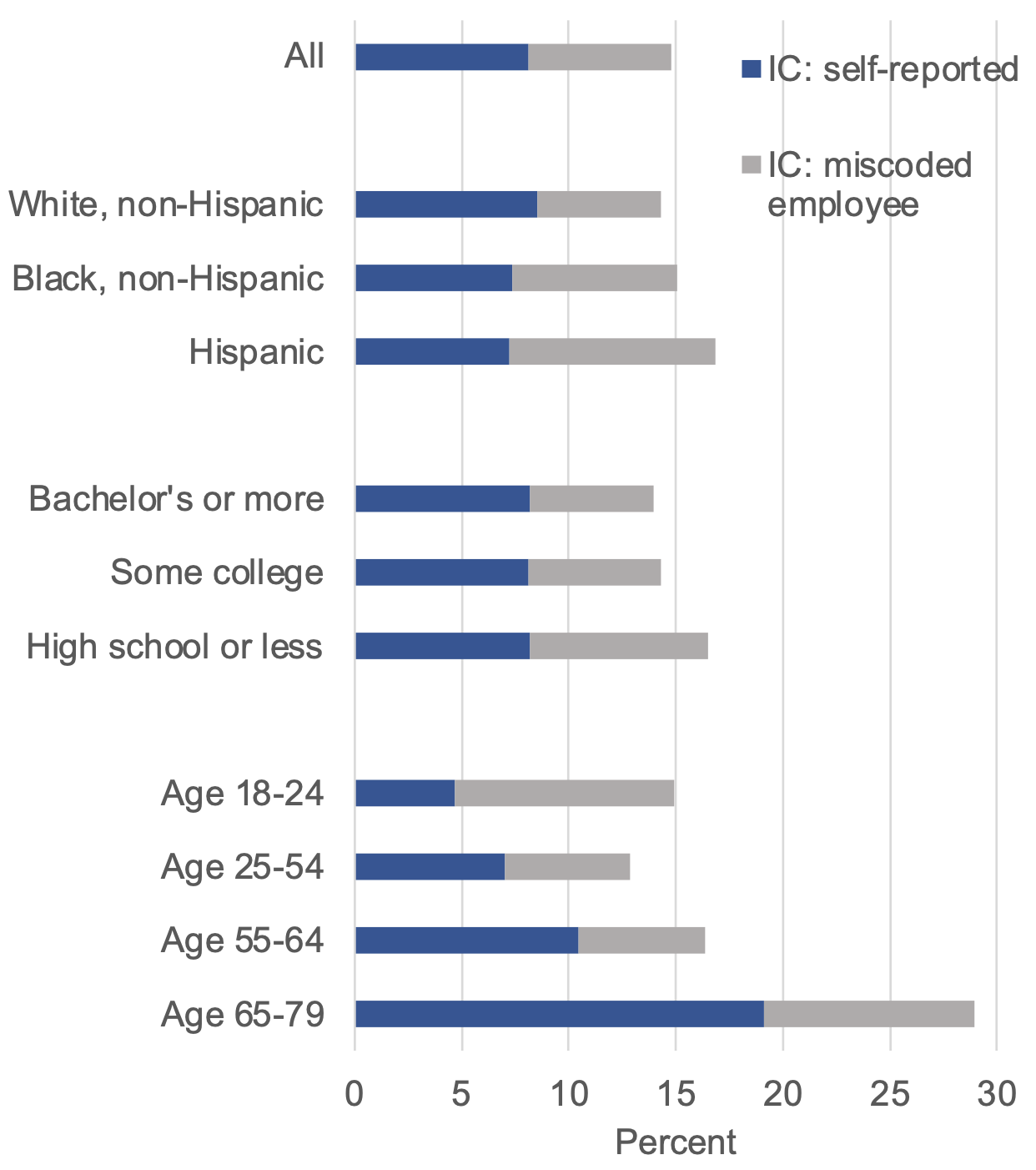

This adjustment matters more for some demographic groups than others, as Figure 2 shows. When we do not account for employee miscoding (blue bars), our data indicate that the prevalence of contract work on a person’s main job is higher among white workers, varies little by education, and rises consistently with age. This unadjusted pattern is similar to the pattern that emerges from Contingent Worker Supplement data (not shown).

Figure 2 The estimated share of workers who are independent contractors on their main job rises sharply when miscoding is corrected

Notes: ‘IC’ is independent contractor. Miscoded employees are those ‘employed by an employer’ on their main job who, when asked a probing question, indicate that they are an independent contractor on that job. See Abraham et al. (2023) for details. Source: Authors’ analysis of Gallup Contract Work module data.

Once we account for miscoded workers (grey bars), however, these patterns change substantially, with contracting more likely among Black and Hispanic workers than among white workers, more likely among those without college education than among those who have attended college, and more likely among younger workers than among prime-age workers.

By probing for all work done in the prior week, our survey also uncovered substantially more secondary job holding than is common in standard household surveys. We find that independent contracting and informal work are especially prevalent in second jobs. Documenting multiple income streams is important for understanding how workers, particularly low-income workers, make ends meet (Abraham and Houseman 2019).

Importance for research and policy

Standard household surveys generally distinguish whether a worker is an employee or self-employed by asking whether the worker is employed by an organisation or is self-employed. In our survey, nearly half of independent contractors are miscoded as employees based on asking this sort of question.

Our findings also suggest that the composition of the independent contractor workforce is substantially different than prior data have indicated. Adding questions that probe for clarification on a worker’s employment arrangements and ask about second jobs is critical for accurately measuring independent contractor work.

While policy debates continue and research on platform work and other non-standard work arrangements is growing rapidly (e.g. Silberman et al. 2019, Datta 2019, Ziegler and van der Klaauw 2019, Nickerson et al. 2020, Koustas and Asai 2022), good data on the size and composition of the independent contractor workforce have been elusive. Accurately identifying contract work in household surveys is an essential step toward understanding the short- and long-term consequences of these work arrangements for workers’ wellbeing. Such research on the independent contractor workforce, in turn, is essential to making informed decisions about the policies and rules that govern these arrangements.

References

Abraham, K G, B Hershbein, S N Houseman, and B C Truesdale (2023), “The independent contractor workforce: New evidence on its size and composition and ways to improve its measurement in household surveys”, NBER Working Paper 30997.

Abraham, K G, and S N Houseman (2019), “Making ends meet: The role of informal work in supplementing Americans’ income”, Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5(5): 110–31.

Abraham, K G, and S N Houseman (2020), “Contingent and alternative employment: Lessons from the contingent worker supplement, 1995–2017”, Washington, DC: US Department of Labor.

Abraham, K G, and S N Houseman (2022), “What do we know about alternative work arrangements in the US? A synthesis of research evidence from household surveys, and administrative data”, WE Upjohn Institute for Emplyoment Research Report.

Datta, N (2019), “Willing to pay for security: Gig workers, freelancers, and the self-employed want steady jobs”, VoxEU.org, 19 July.

Koustas, D, and Y Asai (2022), “Temporary work contracts and female labour market outcomes”, VoxEU.org, 23 June.

NASEM - National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2020), Measuring alternative work arrangements for research and policy, Washington, DC: National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.

Nickerson, J, N Hamdi, A Kalda, and V Fos (2020), “Gig labour as private insurance”, VoxEU.org, 29 March.

Silberman, M, U Rani, M Furrer, E Harmon, and J Berg (2019), “Working conditions on digital labour platforms: Opportunities, challenges, and the quest for decent work”, VoxEU.org, 20 September.

Smith, J (2023), “Mass., California moving in different directions on gig worker issue”, CommonWealth Magazine, 16 March.

Telford, T (2022), “Biden wants to let gig workers be employees. Here’s why it matters”, Washington Post, 17 October.

Ziegler, L, and B van der Klaauw (2019), “Promoting temporary work as an active labour market programme”, VoxEU.org, 2 May.