Civil conflicts tend to recur, leaving legacies of hatred and animosity. To secure peace and prosperity in the aftermath of a civil conflict, it is therefore fundamental to break these cycles of violence.

Historians and social scientists have long emphasised the role of memory in the unfolding of a permanent and stable reconciliation process. Indeed, memories and narratives about the causes and consequences of past wars, the deployment of violence, and the settlement of disputes provide “a collective dimension to private pain, creating a long-lasting healing mechanism” (Hamber 2003). For example, Cilliers et al. (2016) document the prosocial and psychological effects of participating in “truth and reconciliation” commissions after a civil conflict, where victims and perpetrators sat side by side to revive and confess the atrocities of a war.

However, the narratives forged for the purpose of peacebuilding often present a selected and even manipulated recollection of facts. In this column, we illustrate how, in a post-conflict society, versions of the past that promote unity at the expense of truth may foster new cleavages and tensions, ultimately hindering the reconciliation process.

Methodological challenges

Studying the role of narratives for peace poses several empirical challenges. First of all, observing narratives and mapping their spread is often impossible. Moreover, in historical or conflict-ridden contexts with a limited availability of surveys, it is difficult to monitor attitudes and beliefs in order to study how they are affected by narratives. Lastly, assessing the causal effect of narratives means relying on plausibly exogenous variations that are tricky to uncover in real life settings.

As a consequence of these methodological challenges, while anecdotes and case studies about the role of war memories abound, causal evidence is limited. Do historical narratives meaningfully change opinions and behaviours? Or are they rather window-dressing explanations of economic and political processes that involve deeper stakes and special interests?

The Lost Cause narrative and The Birth of a Nation

In a recent paper (Esposito et al. 2021), we study how narratives contributed to national reconciliation after the American Civil War (1861–65). In the aftermath of the war, a powerful narrative known as the Lost Cause emerged. According to this revisionist retelling of US history, the conflict was not caused by slavery. Instead, the South fought simply to defend its freedoms and neither of the two sides had been truly wrong; the real threat to both North and South was represented by the empowerment of black people.

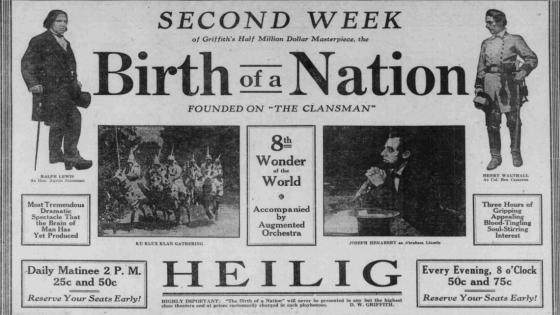

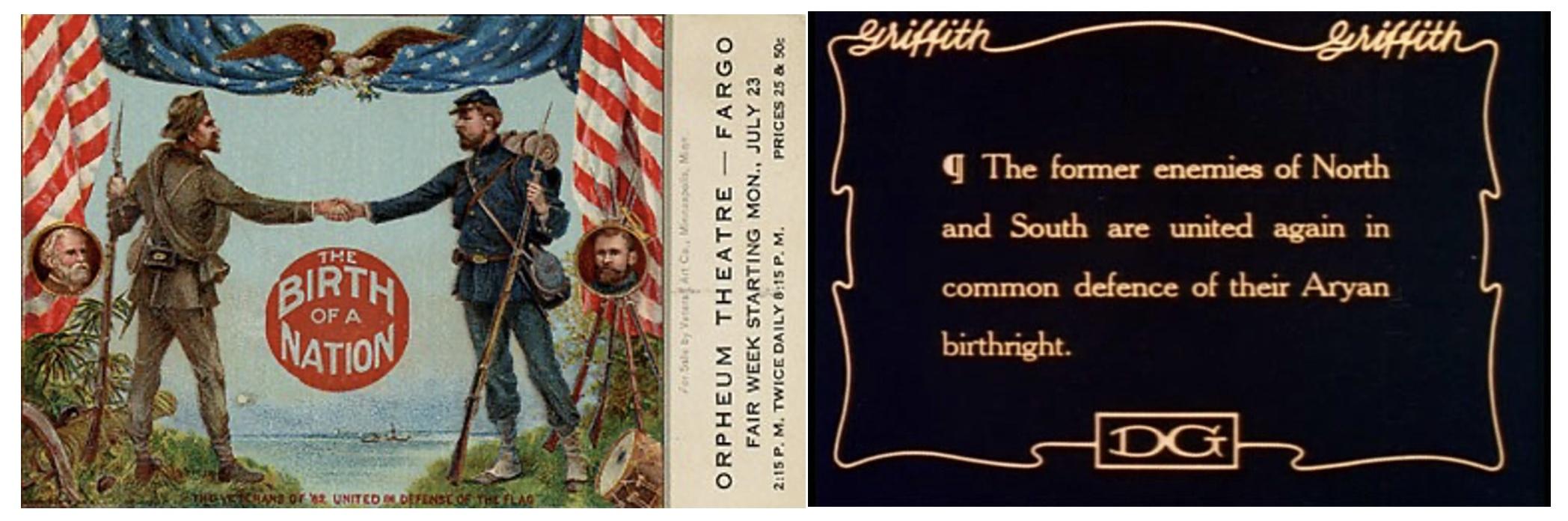

A major flag bearer of the Lost Cause, responsible for popularising this myth throughout the country, was the movie The Birth of a Nation (1915) by director D.W. Griffith. The film was a phenomenal box office success, with a cumulative worldwide audience of more than 200 million people, making it the first Hollywood hit and, according to some critics, one of the most influential films in US cinema history. The movie champions an extreme version of the Lost Cause narrative. A racist portrayal of African Americans and their emancipation struggle, it glorifies the violence of the Ku Klux Klan and advocates for national reunification in defence of white supremacy (see transcripts of the movie in Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 An advert for The Birth of a Nation at the Orpheum Theatre (left) and a script from the movie’s inception (right)

Our study sheds light on how effective the movie was in pacifying North-South divisions and, at the same time, how the common-enemy content of the narrative contributed to the upsurge of violence and discrimination against African Americans. Importantly, our findings reveal how instrumental this disturbing message was in fostering reconciliation. It also complements previous research about how impactful the movie was in terms of inciting violence and hatred towards African Americans (Ang 2020). Note that this logic of common-enemy narratives is not specific to US history. In a recent column, Acemoglu et al. (2020) discuss how Fascists in post-WWI Italy exploited the perceived threat of socialism to gain support among the elite and the middle classes.

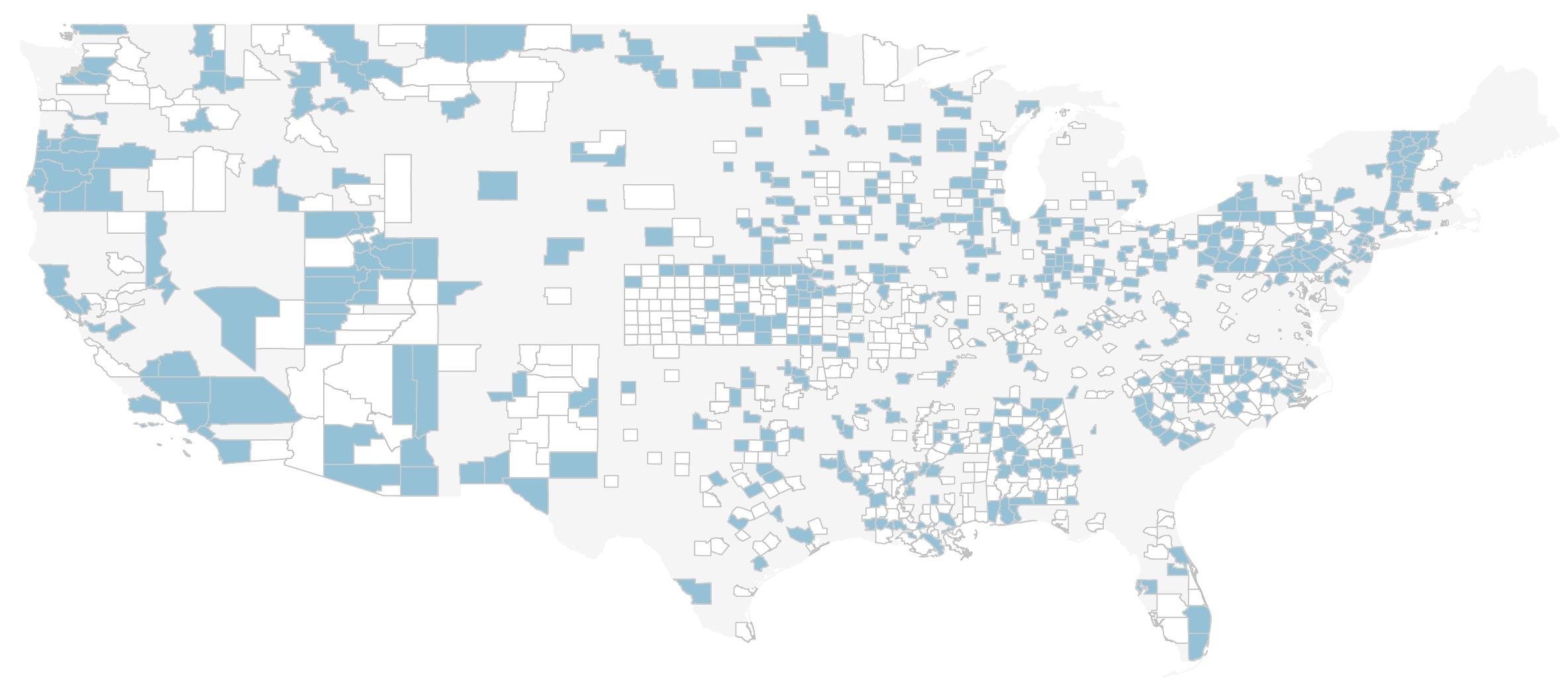

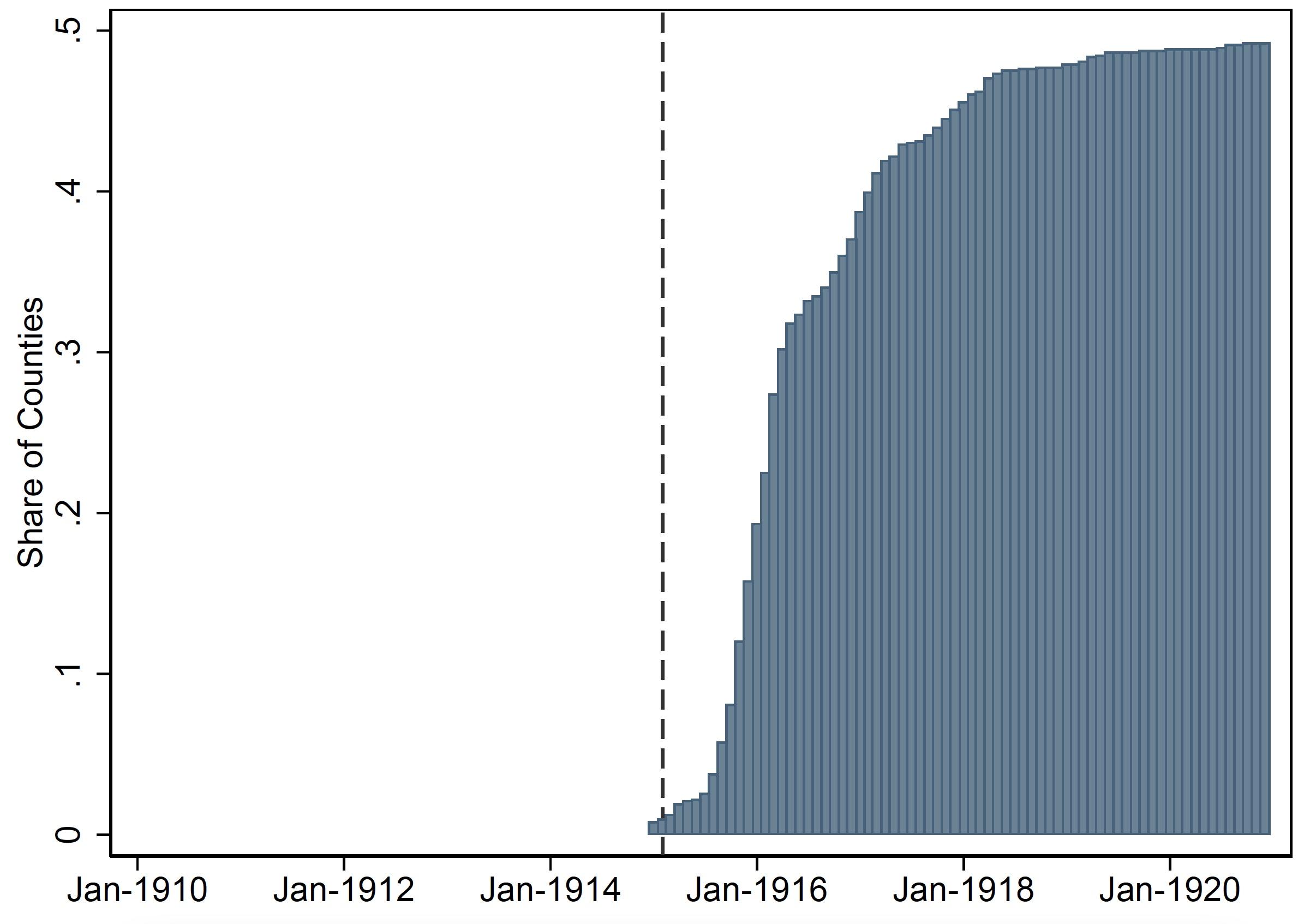

In our analysis, we track the distribution of the movie through US counties (Figure 2). We rely on an extensive data-collection exercise using movie ads in local newspapers to document the movie’s spread from its release in 1915 until reaching about half of the counties in our sample in 1920 (Figure 2). We then look at how the screening of the movie concurred to transform a variety of attitudes towards reconciliation, which we measure on a monthly basis over the full 1910–1920 period, comparing changes in attitudes between counties that screened the movie and counties that did not.

Clearly, a first order concern is that airing the movie was not random. For example, the data show that areas with a higher share of literate inhabitants were more likely to screen the movie. As a source of quasi-exogenous variations in movie exposure, we exploit a feature of the logistics of movie distribution in the early 20th century US: Movies were touring places following recurrent temporal and spatial patterns. We therefore use a previously released movie with content completely unrelated to the plot of The Birth of a Nation to predict where and when the latter was more likely to be screened.

Figure 2 Counties that had screened The Birth of a Nation by 1920* (top) and the share of counties that screened The Birth of a Nation over time (bottom)

Note: * Blue counties were exposed to the movie; white counties were not.

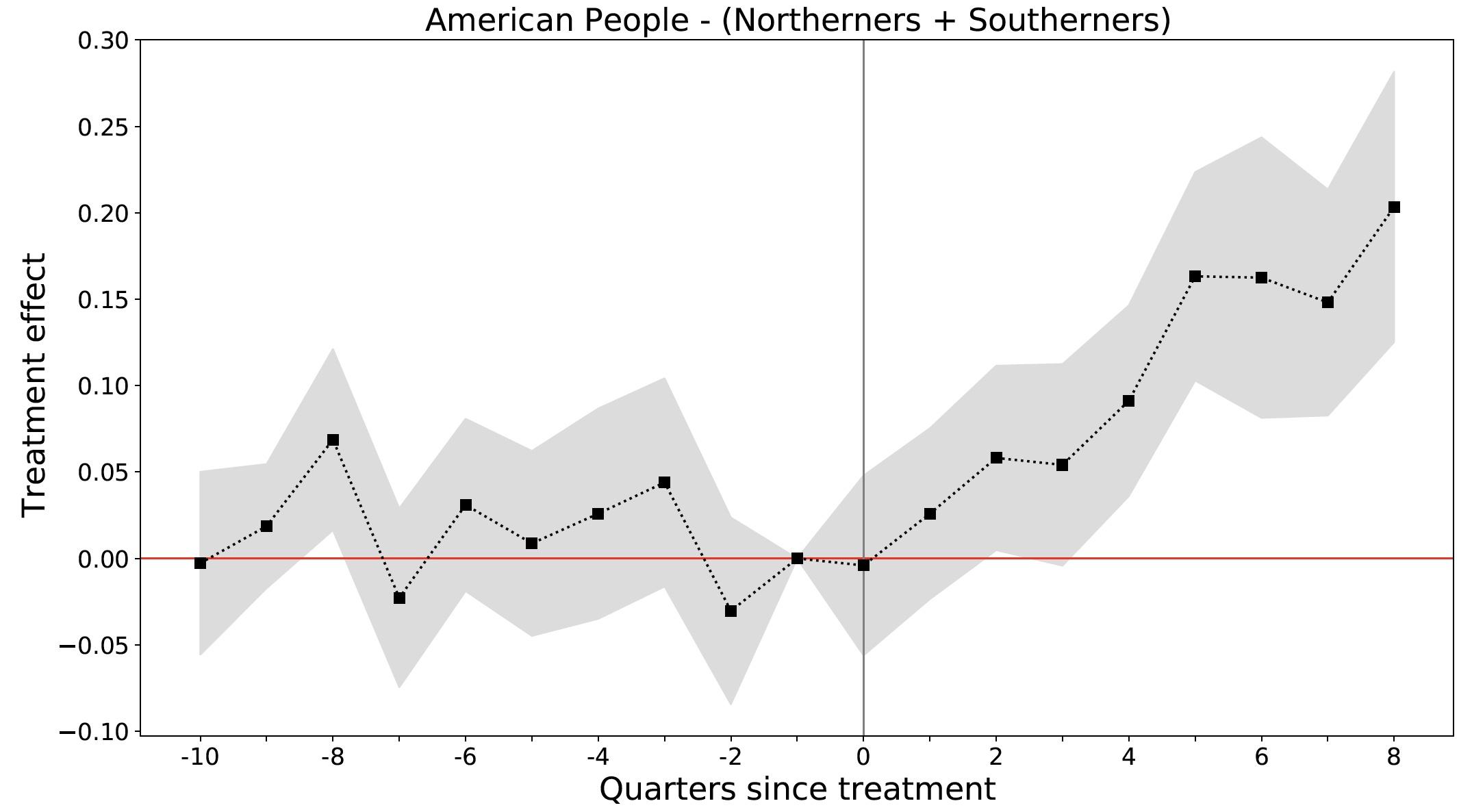

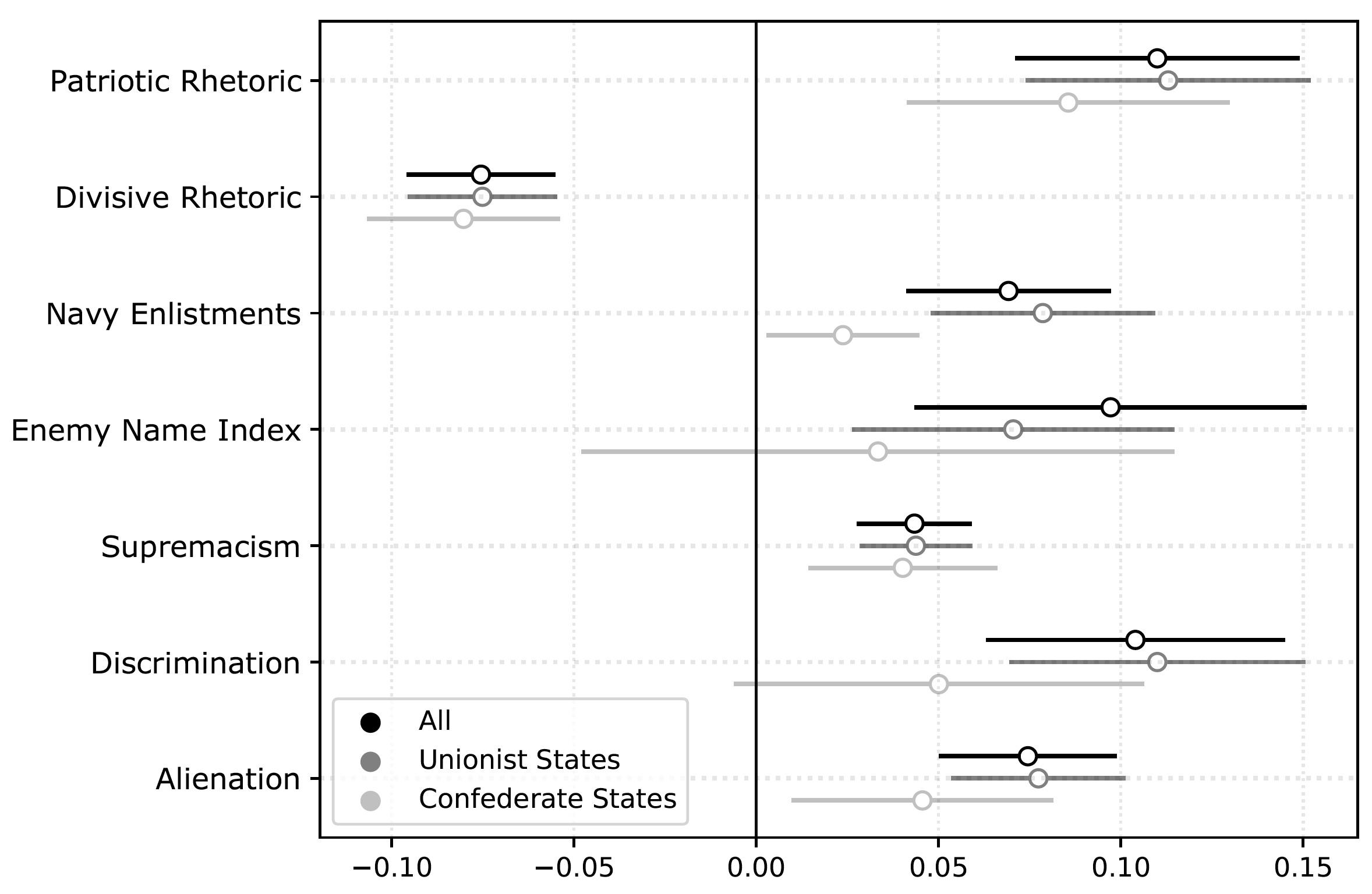

Figure 3 Effects of screenings of The Birth of a Nation

Notes: The top panel shows estimates of the effect that screenings of The Birth of a Nation, including leads and lagged values, had on the relative frequency of the terms ‘American People’ versus ‘Northerner’ or ‘Southerner’. The bottom panel shows coefficient estimates of the effect that screenings of The Birth of a Nation had on an index of patriotic words, an index of divisive words, enlistment rate in the US navy, popularity of the former enemy’s first names, and three different measures of discrimination and alienation of African Americans. See Esposito et al. (2021) for further details on variable definition and construction.

Our statistical estimations point to a quantitatively sizeable effect of the movie on a series of attitudes towards national reconciliation and the alienation of African Americans (Figure 3). Our first measure of national unity is derived from a text analysis of a large dataset of local newspaper articles containing more than 25 million pages. In the data, we see that screening The Birth of a Nation led to an immediate and continuously growing increase in the frequency of patriotic terms (e.g. “united country”, “stars and stripes”). By contrast, words related to former North-South cleavages (e.g. “Confederacy”, “scalawag”, “carpetbagger”, etc.) tend to be used less frequently. As illustrated by Figure 3, six quarters after screening began, the relative frequency of the patriotic terms “American people” with respect to the divisive words “Northerners” and “Southerners” increased by 17%.

Beyond shifts in language, the movie also effected behaviours. We show that counties exposed to the movie experienced a surge in patriotism with an increase in the rate of volunteering for the US military. Looking at naming patterns among babies born in counties that aired the movie, we find that the movie facilitated cultural reconciliation between North and South, with an increased adoption of first names traditionally associated with the former enemy’s regional identity.

The cost of the non-inclusive reconciliation narrative conveyed by the movie, rooted in a common enemy argument, was dramatic. By measuring the salience of white supremacism and racial discrimination in local newspapers, we can quantify how much the movie contributed to the alienation of African Americans. What is more, a methodological experiment enables us to assess what role the common enemy narrative played in boosting the reconciliation purpose of the movie. According to our estimates, about half of the total effect of the movie on reconciliation was indirectly mediated through a rise in the alienation of African Americans. These results suggest that reconciliation was fostered by reshuffling anger and animosity from the North-South to the Black-White cleavage. Specifically, the Lost Cause narrative forged the myth of a common threat to all white Americans from North and South: Black Americans and their fight for enfranchisement.

Our findings offer a new interpretation of the role of the Lost Cause in moulding internal cleavages that remain at the core of political debate today. More broadly, our paper questions the ability to reunite as one nation when reconciliation is based on excluding some of its members.

References

Acemoğlu, D, G De Feo, G De Luca and G Russo (2020), “Revisiting the rise of Italian fascism”, VoxEU.org, 28 October.

Ang, D (2020), “The birth of a nation: Media and racial hate”, HKS Working Paper No. RWP20-038

Cilliers, J, O Dube and B Siddiqi (2016), “Reconciling after civil conflict increases social capital but decreases individual well-being”, Science 352(6287): 787–794.

Esposito E, T Rotesi, A Saia and M Thoenig (2021), “Reconciliation Narratives: The Birth of a Nation after the US Civil War”, CEPR Working Paper 15938.

B Hamber (2003), Reconciliation After Violent Conflict: A Handbook (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance).