There is broad consensus on competition policy when it comes to dealing with horizontal mergers (Motta 2014). Acquisitions can lead to anticompetitive effects if the merging firms take into account the impact of their actions on each other's profits. In mergers between firms that offer substitute products, competition authorities regularly assess (e.g. Valletti and Zenger 2018):

- Concentration, as indicated by the market shares of merging firms.

- Closeness of competition, as indicated by the cross-price elasticities between the merging firms.

- Pricing power, as indicated by the profit margins of merging firms.

But assessing these three indicators for social media platforms is complicated. In recent years there have been a number of large social media mergers, such as the $1 billion acquisition of Instagram by Facebook in 2012 and the $19 billion acquisition of WhatsApp, also by Facebook, in 2014.

In a standard horizontal merger, competition authorities typically define markets in terms of substitutability in response to relative price changes. They seek to understand how the merger will affect prices, quantities, and other variables that affect consumer welfare. But how do we proceed when the merging companies are social media platforms? These firms are mostly giving away their product for free, and then making money from advertisers.

Unsurprisingly, competition authorities have struggled to do this with social media platforms. They cleared both the Instagram and the Whatsapp acquisitions on the basis of assessments that used established, standard, notions of market definition.

The FTC investigation into the Instagram acquisition focused on camera apps. It found that Facebook would not have had a monopoly in photo-taking and sharing apps if the deal closed, because it faced competition from other photo sharing apps, such as Camera+ and Hipstamatic.

The same merger was also cleared by the UK Office of Fair Trading. It observedthat, at the time, Instagram did not generate revenues from advertising and therefore was not an important competitor of Facebook for advertisers. For both authorities, the starting point of the investigation was the market for camera apps.

The European Commission's WhatsApp merger assessment started from an analysis of the market for messaging apps.

When markets are multi-sided, the problem of market definition is empirical. There is almost no price variation on the user side to measure substitutability, and therefore many authorities have fallen back on functional definitions (camera apps, for example) that do not capture how competition takes place.

A blind spot

Policymakers and scholars are questioning this approach. Does it make sense to extend tools that were designed for standard industries to industries that are radically different? Wu (2018) described this approach as a 'blind spot' of existing competition policy, arguing that the market power of social media companies is not manifest in standard consumer market definitions.

These companies are 'attention brokers' – they capture the attention of their users and sell it to advertisers. Platforms compete against each other to keep this attention on their platform. Focusing on attention also avoids the possibility that there is currently no overlap in advertising simply because competing platforms are at different stages of their lifecycle. For example, Instagram did not carry advertising at the time of the Facebook merger because it was focusing on user growth, to be monetised in the long run.

The effect of a merger should therefore be evaluated by trying to understand whether it will lead to an increase in concentration in the market for attention, and whether this increase is likely to hurt consumer welfare. But how do we quantify the market power of attention brokers? And how do we assess the effect a merger between attention brokers will have on consumer welfare?

An attention oligopoly

Our recent work (Prat and Valletti 2018) attempts to formalise and quantify some of these issues. We model three layers of actors in a specific setting: consumers, social media platforms, and producers. In our model, producers sell goods to consumers and can advertise these products through social media. There are many social media platforms. Consumers differ in their social media usage and may multi-home among platforms. Social media platforms use competitive selling mechanisms to allocate advertisements to firms.

In this idealised environment, browsing data and artificial intelligence allow platforms to identify individual consumption preferences and to sell individually targeted advertisements to producers. This is not reality yet, but it describes one function of AI, according to Larry Page, one of Google’s founders:

"Artificial intelligence would be the ultimate version of Google. The ultimate search engine that would understand everything on the web. It would understand exactly what you wanted, and it would give you the right thing. We're nowhere near doing that now. However, we can get incrementally closer to that, and that is basically what we work on."

Academy of Achievement (2000)

This strikes us as a better reflection of hyper-targeted advertising using 'big data', as opposed to the old view of advertising trying to gain generic 'eyeballs' that could be reached in all sorts of ways, from billboards to newspapers.

Producers may be incumbents or entrants. The products of incumbents are more familiar to consumers than those of entrants. Targeted advertising can help entrants close this informational gap. We assume that a consumer's surplus is higher if he is aware of the entrant's product, but this reduces the incumbent's revenue. Every platform used by an individual sells the right to run targeted advertisements to that individual through a competitive selling mechanism, such as a standard second-price auction.

In this environment, each consumer is an individual market. The probability that the consumer becomes aware of the entrant's product increases with the number of independently owned platforms used by that consumer. Aggregating across consumers, we express overall consumer welfare on the basis of platform usage patterns. Under some simplifying assumptions, consumer welfare is a decreasing function of a simple concentration index that depends on measurable parameters such as the share of consumers who use a certain subset of platforms and the number of independently-owned platforms in that subset. Welfare is higher if consumers use many platforms, because it is more expensive for the incumbent to keep consumers uninformed about the entrant's product.

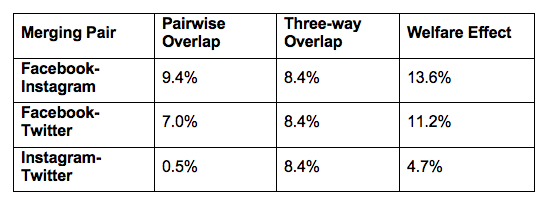

We can use this concentration index to assess the potential effect of a merger by using information on individual social media consumption patterns. For instance the 2016 Pew Institute Survey on Social Media Trends (Gottfried and Shearer 2016) asked more than 4,500 Americans about how they used Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Using that table, we computed the welfare effect of any bilateral merger between these three platforms (one merger actually has already taken place, two are hypothetical)

Table 1 Welfare effect of bilateral mergers for three social media sites

Source: Prat and Valletti (2018), based on 2016 data from Pew Research.

The welfare effect of a Facebook-Instagram merger was highest because this pair has a larger share of consumer overlap than the other two pairs.

The idea is simple. 'Attention' of users is a scarce resource that is controlled by platforms. These platforms can become bottlenecks for producers that want to reach consumers who use a small set of platforms. In turn, this hurts users. They end up with less product choice, paying higher prices.

When online platforms with overlapping consumers merge, they set prices for advertisements that select incumbent producers to the detriment of entrants. In this sense, online platform market power is not good for innovative entrants (who need advertisements to be known by users), nor for users (who will buy at a high price from incumbent producers). Market power begets market power.

Impact on competition policy

Our paper assesses competition between ad-funded platforms through a relevant metric based on users' attention overlaps. This assessment does not require a radical departure from existing competition policy. Instead, it correctly applies first-order economic principles to these markets.

In a specific example that focuses on product markets, we can show that as online platforms become more concentrated, competition for advertisement scarcity benefits incumbent producers. A merger between online platforms allows them to better control this scarcity, tilting the game even more in favour of incumbents. The mechanism extends beyond the specific example, as long as platform concentration results in reduced incentives to produce attractive services for the users.

The crucial element in an online merger assessment (as in any other merger) is to look at the overlap of users across platforms. If consumers multi-home, scarcity is more likely to disappear, making entry also more likely.

A problematic merger would therefore be one between concentrated online platforms with overlapping users. Standard metrics that ignore these overlaps and just concentrate on usage can lead to large biases. And metrics that focus only on the supply-side – market shares – are inappropriate in online markets.

References

Academy of Achievement (2000), "Interview: Larry Page", 28 October.

Motta, M (2014), Competition Policy: Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press

Gottfried, G and E Shearer (2016), "News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016", Pew Research Center, 26 May.

Prat, A and T Valletti (2018), "Attention Oligopoly", working paper.

Valletti, T and H Zenger (2018), “Should profit margins play a more decisive role in merger control?”, Journal of European Competition Law & Practice 9: 336-342.

Wu, T (2018), “Blind Spot: The Attention Economy and the Law”, Antitrust Law Journal 82, forthcoming.

Endnotes

[1] After the Cambridge Analytica scandal, many people deleted their Facebook account to migrate to Instagram, which is owned by the same company.