Protectionism has been on the rise in recent years. Brexit and the China-US trade war are but a couple of examples marking the shift from previous traditions of openness towards the mobility of people, goods, and services. There is much support for the contention that restriction of trade and imposed barriers to cross-border movement are associated with a net economic loss (Delpeuch et al. 2021).

Amiti et al. (2019) calculated the deadweight cost of welfare following the protectionist actions by the Trump administration during the 2018 China-US trade war. The decrease in US real income amounted to approximately $6.9 billion during the first 11 months of 2018, with an additional cost imposed on domestic consumers and importers in the form of tariffs at roughly $12.3 billion.

Economic evaluations of Brexit provide evidence that anti-globalisation comes with a significant price tag (e.g. Goldin et al. 2018). However, political decisions, such as imposing restrictions on labor migration and reshoring factories may seem futile compared to what is happening right now.

Since 2020, there has been a sharp increase in the kind of agendas and political rhetoric that smacks of political realist (Waltz 1979) sentiments heralding that “everyone will need to fend for themselves”.

Although there is a relatively clear understanding of the costs of trade-wars and Brexit, the implications of COVID-19 are not as well understood (Coibion et al. 2020). Thus, the pandemic has further increased the need for understanding the relationship between determinants of trade and internationalisation, such as migration.

Policies aimed at economic recovery will undoubtedly include the restoration of trade and other forms of internationalisation, and there will need to be a balance between curbing pandemics and facilitating the mobility of people, services, and goods. As vaccinations become readily available on a global scale, a discussion of how to best reopen, reboot, and restore economies for a post-pandemic world becomes more important.

In a recent study (Hatzigeorgiou et al. 2021a), we use evidence from over 100 research papers to draw inferences on the migrants’ roles on international trade, foreign direct investment, and offshoring. Data are inferred from studies at macro-, sub-national- and micro-levels.

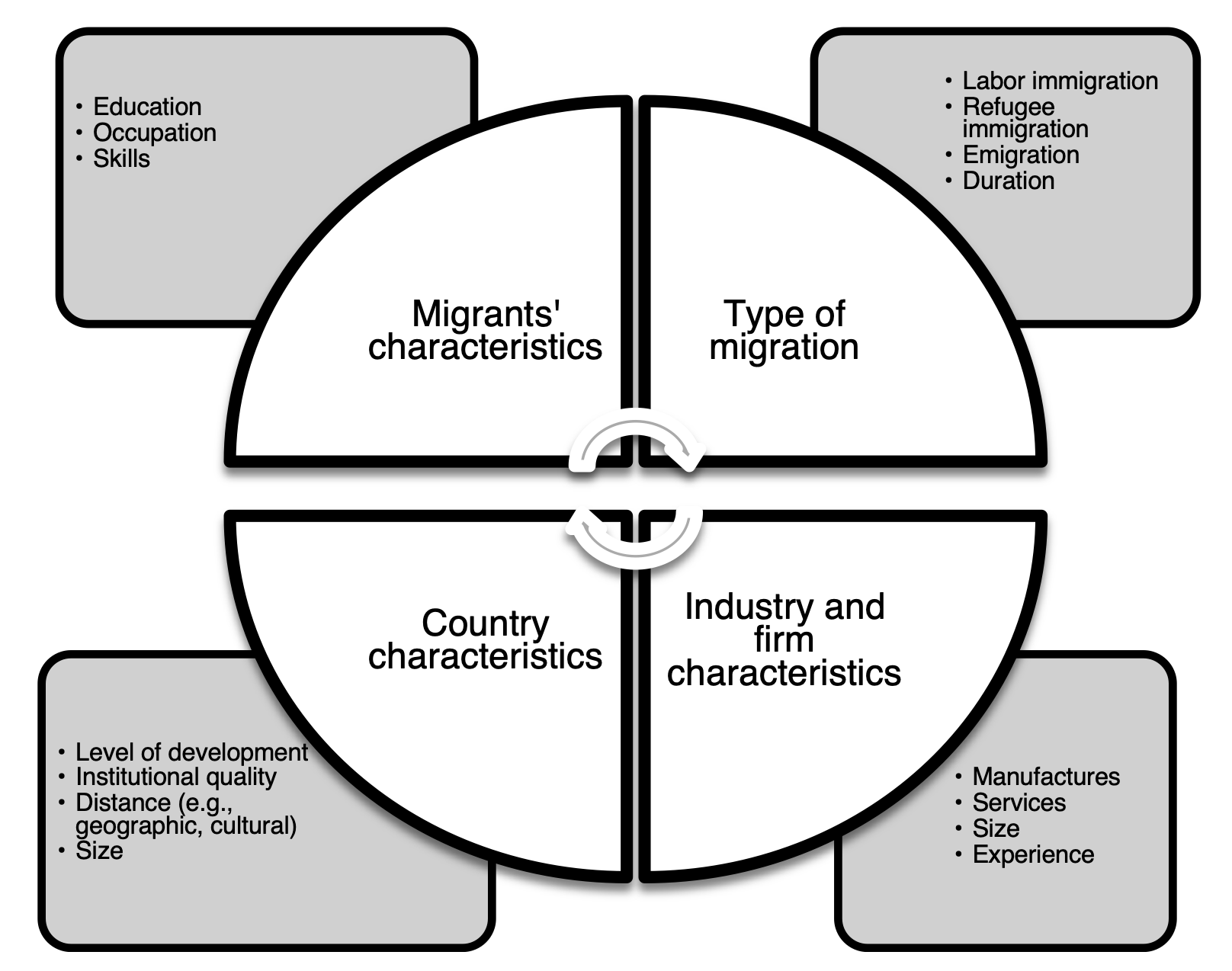

Whereas traditional views suggest migration and trade are substitutable, the contemporary contention is that trade and migration complement each other (e.g. Gould 1994, White 2007, Vézina 2012, Aleksynska et al. 2014, Parrotta et al. 2016). Figure 1 summarises theoretical conjectures on key dimensions of the trade-migration relationship.

Figure 1 Factors that could influence the relationship between migration and trade

Source: Hatzigeorgiou et al. (2021a).

The model identifies the factors that could affect the impact of migrants on firms’ internationalisation. The upper part of the model relates the probability and/or intensity of internationalisation to the characteristics of migrants and the reason for leaving the home country. For example, immigrants’ education level and skills will likely determine their future positions in firms and therefore the level of influence on the trade and internationalisation decisions of those firms. The lower part of the model relates to the characteristics of the firms and the countries involved in firms’ internationalisation. For example, migrants are expected to differentially promote trade with their home country dependent on its characteristics, such as cultural and institutional dissimilarity, and the products to be traded by the firms.

Evidence suggests migration spurs internationalisation

Macro-level studies on the migration-trade nexus suggest that migration is strongly related to immigrant host countries’ imports relative to exports. The aggregated picture of the studies shows that the elasticity of trade with respect to immigration is approximately 0.18 for imports and 0.15 for exports (Hatzigeorgiou et al. 2021a). This implies a 1% increase in a country’s foreign-born population is associated with a 0.18% increase in imports and a 0.15% increase in exports with immigrant source countries on average.

The results also indicate that migrants have a relatively high impact on trade in heterogeneous products, compared to homogeneous products. This suggests that the migration-trade link is contingent on the migrants’ ability to improve the information flow between countries while boosting the confidence in business transactions (Casella et al. 2002). Finally, the macro-level results tend to follow the established theory inasmuch as indicating that the impact varies depending on the characteristics of migrants and countries. For example, as seen in Figure 1, stronger linkage is expected between skilled migrants and less developed countries on one hand, and trade on the other.

The sub-national studies utilise regional data to explore the role of migrant stocks across regions within countries. These studies fall in line with macro-level evidence that migration facilitates trade and other forms of internationalisation. The median estimated coefficient provided by these studies is 0.14 for exports and 0.23 for imports, which closely resembles what macro-level evidence show. It should be noted that the variation across studies that initially estimated a positive migrant influence on regional foreign trade has dwindled over time.

The firm-level studies provide the most useful insights. These studies demonstrate that foreign-born employees are associated with increased firms’ exports (Bastos et al. 2012, Hiller 2013, Andrews et al. 2017, Cardoso et al. 2019). Although the micro-level evidence provides support to the main results from the macro-level and sub-national level studies, the firm-level approach is able to put some of the conclusions into perspective. Studies based on employer-employee data that incorporate data for immigrants’ education level reveal that it is likely high-skilled immigrants that possess the greatest possibility of promoting firms’ trade and other forms of internationalization.

Migration and digital technologies

The pandemic has intensified digitalisation. Labour migration and business travel have become difficult or almost impossible during the pandemic. Hyper-digitalisation and the new ways of remote work could potentially harvest some of the benefits from the trade-migration relationship without the requirement of physical migration, through so-called telemigration – foreign-based online workers (Baldwin 2019).

The technological development in communication and artificial intelligence could help to overcome asymmetric information. This will complement the benefits of cross-country cooperation and thus further facilitate internationalisation. For example, the development of artificial intelligence in speech-recognition and machine translation may help to overcome gaps in knowledge and foster communications where there have naturally been obstacles before (Brynjolfsson 2018). In the long run, this could change both the way we think about labor, movement of persons and international trade (Lund et al. 2019).

Even if the potential of telemigration is immense for the global economy (Baldwin 2019), for now, there are likely restraints in how technology could substitute for migration in the trade-migration relationship. In this regard, we conclude that employed immigrants contribute with tacit knowledge about their home country and facilitate for firms that wish to discover, establish, and maintain successful business relationships with firms in foreign countries. To exploit these potential opportunities and create productive synergies at the workplace, current technology may be of help primarily by complementing rather than replacing migrants as conduits for knowledge and links to foreign markets.

Conclusion

The rhetoric in this past decade has gravitated towards a more nation-centric tone in terms of both migration and trade (Bahar et al. 2020). However, evidence from studies on different levels of the migration-trade nexus suggests that migration facilitates international trade and promotes foreign direct investment as well as offshoring (Hatzigeorgiou et al. 2021a).

These conclusions provide useful insights on how to reboot and revitalise economies in the wake of COVID-19. In designing and implementing strategies for economic recovery, policymakers should consider the role of migration—especially skilled labor migration—in promoting internationalisation and growth. Furthermore, policymakers could exploit advances in technology and new working practices to complement migrants in promoting firms’ internationalisation.

References

Aleksynska, M, and G Peri (2014), “Isolating the Network Effect of Immigrants on Trade”, The World Economy, 37 (3): 434–455.

Amiti, M, S J Redding, and D Weinstein (2019), “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare”, NBER Working Paper 25672.

Andrews M, T Schank, and R Upward (2017), “Do Foreign Workers Reduce Trade Barriers? Microeconomic Evidence”, The World Economy, 40 (9): 1750–1774.

Bahar, D, R Choudhury, and H Rapoport (2020), “How migration helps countries become competitive at innovating in new technologies”, VoxEU.org, 28 February.

Baldwin, R (2019), The globotics upheaval: Globalization, robotics, and the future of work, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bastos, P, and J Silva (2012), “Networks, Firms, and Trade”, Journal of International Economics 87 (2): 352–364.

Brynjolfsson, E, X Hui, and M Liu (2018), “The effect of machine translation on international trade: Evidence from a large digital platform”, VoxEU.org, 16 September.

Cardoso, M, and A Ramanarayanan (2019), “Immigrants and Exports: Firm-Level Evidence from Canada”, University of Western Ontario, Economics Research Report Series No. 2.

Casella, A, and J E Rauch (2002), “Anonymous Market and Group Ties in International Trade”, Journal of International Economics, 58 (1): 19–47.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, and M Weber (2020), ”The Cost of the Covid-19 Crisis: Lockdowns, Macroeconomic Expectations, and Consumer Spending”, NBER Working Paper 27141.

Delpeuch, S, E Fize, and P Martin (2021), ”Trade imbalances and the rise of protectionism”, VoxEU.org, 12 February.

Goldin, I and B Nabarro (2018), ”Losing it: The economics and politics of migration”, VoxEU.org, 24 October.

Gould, D (1994), “Immigrant Links to the Home Country: Empirical Implications for U.S. Bilateral Trade Flows”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 76 (2): 302–316.

Hatzigeorgiou, A, and M Lodefalk (2021a), ”A literature review of the nexus between migration and internationalization”, The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 30 (3) 319–340, DOI: 10.1080/09638199.2021.1878257.

Hatzigeorgiou, A, P Karpaty, R Kneller, and M Lodefalk (2021b), ”Migrant Employment and the Contract Enforcement Costs of Offshoring”, manuscript.

Hiller, S (2013),“Does Immigrant Employment Matter for Export Sales? Evidence from Denmark”, Review of World Economics, 149 (2), 369–394.

Lund, S, and J Bughin (2019), ”Next-generation technologies and the future of trade”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Parrotta, P, D Pozzoli, and D Sala (2016), “Ethnic Diversity and Firms’ Export Behavior”, European Economic Review 89 (C): 248–263.

Vézina, P-L (2012), “How Migrant Networks Facilitate Trade: Evidence from Swiss Exports”, Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 148 (3): 449–476.

Waltz, K (1979), Theory of International Politics, Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

White, R (2007), “Immigrant-trade Links, Transplanted Home Bias and Network Effects”, Applied Economics 39 (7): 839–852.