Globalisation has not only led to an increase in international trade and finance but is also accompanied by massive flows of people from poorer regions in the Global South to richer regions in the North. Wars, underdevelopment, and poverty have increased the push forces of emigration. At the same time, most countries in the North have raised the obstacles to legal migration and are investing more resources in border enforcement. Initially, public opinion in many European countries was generally pro-migration, be it for economic reasons related to population aging or for humanitarian reasons. This has changed at least since 2015, with the advent of the so-called refugee crisis, which made evident the rift across and within EU countries.

The Global Compact for Migration and debates in the EU parliament and national parliaments have made illegal migration one of the fundamental policy issues that need to be dealt with. It has led to national crises, as the collapse of the Belgian government shows. Oftentimes perceptions about facts seem distorted (Alesina et al. 2018). Also, the inclinations of allowing legal migration differ substantially across countries and the orientation of political parties. However, there is a general understanding that illegal migration only exists because of the smuggling industry, leading to widespread agreement that the industry should be tackled both for humanitarian and strategic reasons.

To date, a number of interesting contributions regarding the role of the smuggling industry in illegal migration have emerged in economics. However, there is no reliable information about how the intention and decision to leave Africa and come to Europe depend on the availability of smuggling services. This is an important piece of information needed to evaluate the proposed policies. The fundamental problem with pinpointing this information is related to the oldest of all identification problems, namely, the problem of disentangling demand from supply effects.

The smuggling industry that transports hundreds of thousands of people from Africa to Europe every year is believed to be one of the largest illegal industries worldwide (besides weapons and arms), and its size is estimated at up to $7 billion in 2016 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2018).

History provides an exogenous variation in supply that our recent paper (Friebel et al. 2018) uses to provide an estimate of the supply elasticity of this industry. In 2011, a coalition of governments bombed Libya, and with the quick demise of the Gaddafi regime, the so-called ‘Friendship Treaty’ between Libya and Italy came to an end. The most important component of this treaty was the agreement that the Libyan regime would make sure that refugees would not try to cross the Mediterranean from the large Libyan coastline.

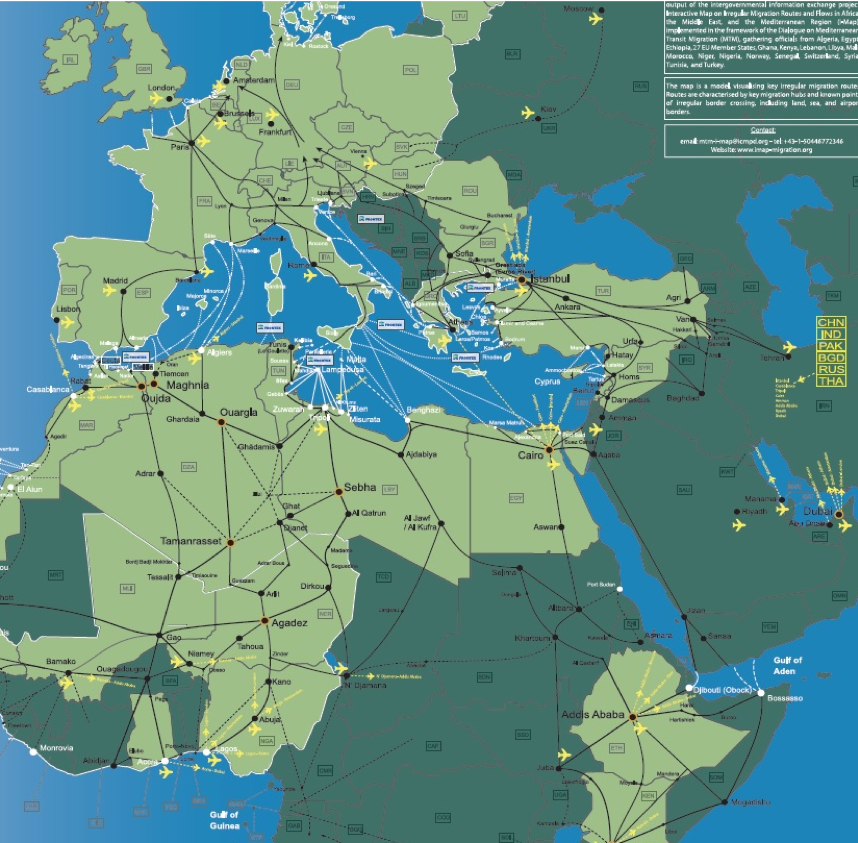

Thus, with the collapse of the Gaddafi regime, the Libyan borders suddenly became available to undocumented migrants. Figure 1 shows all smuggling routes from Africa to Europe, both across sea and land, including the reopened crossings from Libya to Italy (the Central Mediterranean Route). As can be seen on the map, with the possibility of crossing the Mediterranean from Libya to Italy, the bilateral smuggling distance between numerous country-pairs got shorter.

Figure 1 Smuggling routes from Libya

Source: Frontex

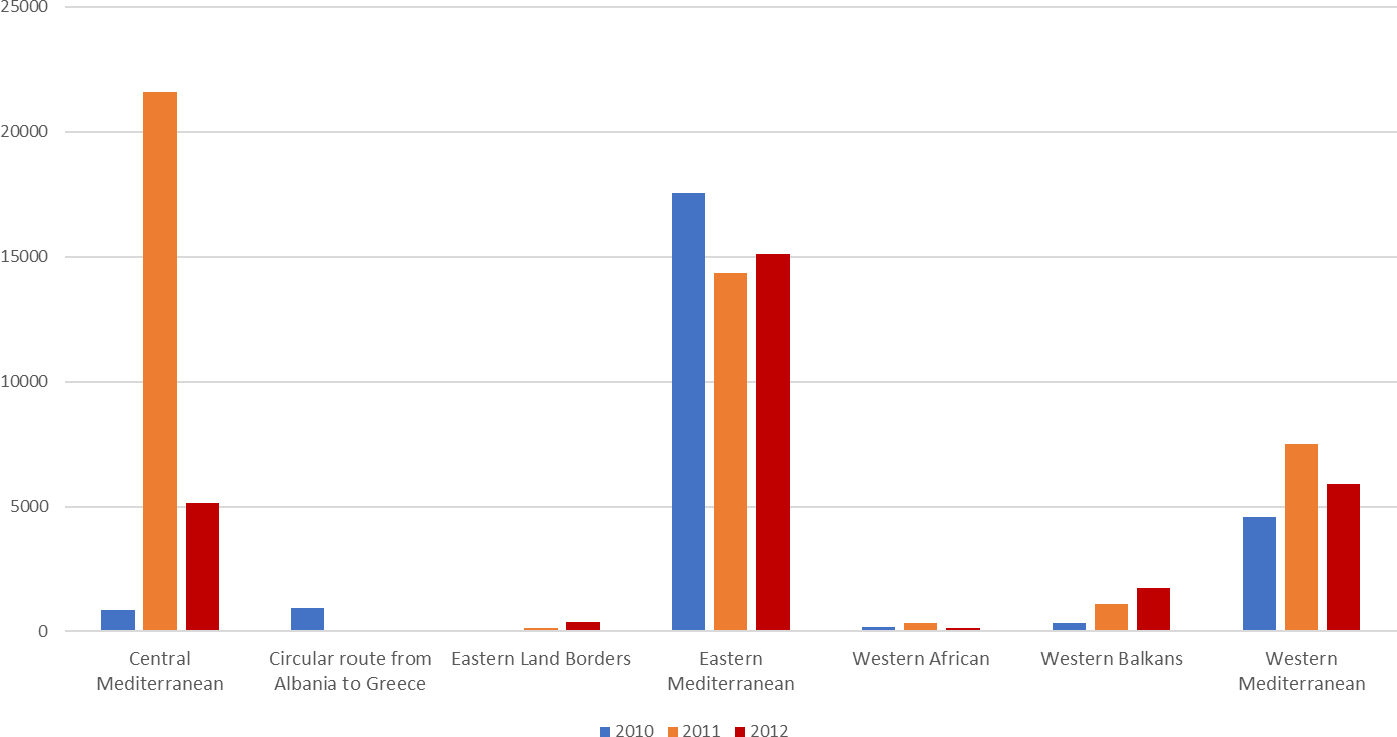

Using data from Frontex on migrant flows arriving at European borders, Figure 2 shows that the opening of the central Mediterranean route in 2011 triggered a surge in migration flows through that route. Leveraging this source of spatial and time variation in irregular migration routes, we estimate the elasticity of migration intentions to illegal moving costs proxied by distance. The research design uses the distance shock but does not focus on the shock itself. Excluding from the analysis the year of the shock (2011) and the countries directly involved in the Arab Spring, we evaluate the unintended effects of the exogenous change in the smuggling distance on individual migration intention throughout the region. We do so by building a novel dataset of geo-localised time-varying migration routes, combined with cross-country survey data by Gallup on individual intentions to move from Africa (and the Middle East) into Europe. Netting out any country-by-time and pair-level confounders, the findings indicate a large negative effect of distance along smuggling routes on individual intentions to migrate.

Figure 2 Number of detected illegal migrants by migration routes

Notes: The figure shows the number of detected illegal migrants (i.e. detected border crossing) arriving in European territory across different migration routes in years 2010, 2011, and 2012. Source: Frontex.

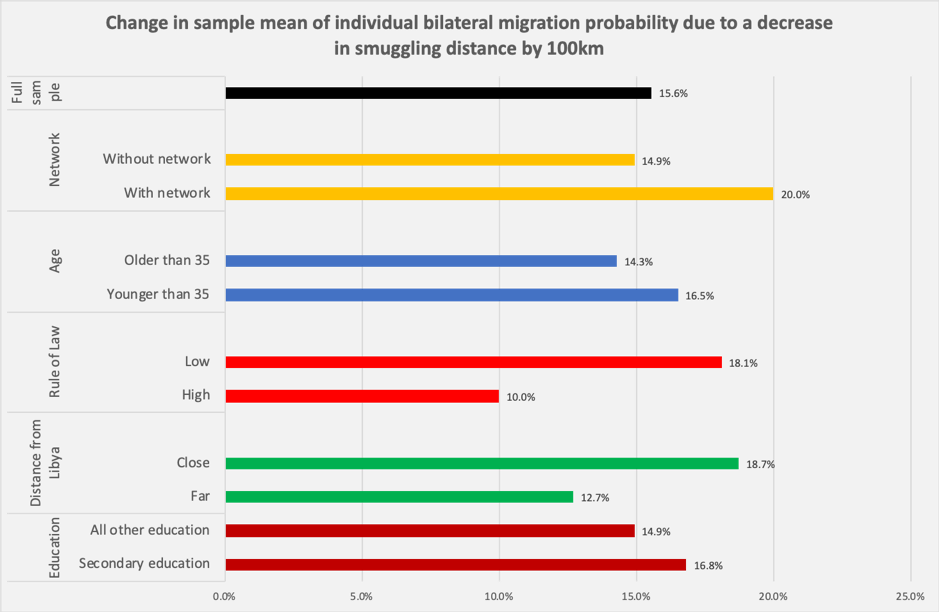

The summary of the magnitude of these effects is shown in Figure 3. For the full sample, there is an estimated 15.6% increase in the sample mean of an individual’s intention to migrate associated with a reduction in smuggling distance by 100 kilometres. To put these numbers into perspective, the average change in bilateral distance before and after 2011 is about 600 kilometres.

There are interesting heterogeneous effects, both at the individual and country levels. Those individuals who have close friends and relatives abroad are much more affected by a reduction in smuggling distance than those without close social networks. In addition, younger people and those with secondary education are also more likely to intend to migrate as smuggling distance decreases. Furthermore, individuals living in countries which are closer to Libya are more affected. Finally, those living in a country where the rule of law is weaker (than the median-level rule of law based on the World Bank Rule of Law index for our sample), are much more affected by the change in smuggling services. More specifically, there is an estimated 18% increase in the sample mean of an individual’s intent to migrate associated with a 100-kilometre decrease in bilateral smuggling distance, while for those living in countries with a higher level of rule of law, this increase is only 11%.

Figure 3 Change in sample mean of individual bilateral migration probability due to a decrease in smuggling distance by 100km

Source: Authors’ calculations.

The latter finding seems to imply that local conditions may matter substantially, not only because a weaker rule of law may make it easier for smugglers to operate in these countries, but also because a weak rule of law may mask worse living conditions. Indeed, the paper finds that the intention to migrate negatively correlates with the satisfaction with local living conditions. Hence this is an important factor to consider when aiming to reduce illegal migration flows.

It would be tempting to think of our results as providing evidence for tackling smuggler networks as the best strategy to reduce migration flows from Southern countries. However, whether this is a feasible strategy is, at the very least, questionable. The speed with which the smuggling industry took off in Libya after the demise of the Gaddafi regime seems to indicate that the smugglers are quick to move and start operating at another place when blocked from running their services.

Providing more legal channels seems to be another alternative, but those rejected or anticipating rejection could still take recourse to illegal channels unless their living conditions were to improve. Coordinating with local governments and international organisations in better screening those eligible to migrate to Europe and doing it in the sending countries, as the European Parliament is discussing, is not without problems. However, it would reduce potential migrants’ uncertainty on their possibility to enter Europe, therefore saving them thousands of kilometres of potentially very dangerous trips.

References

Alesina, A, A Miano and S Stantcheva (2018), “Immigration and redistribution”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13035.

Friebel, G, M Manchin, M Mendola and G Prarolo (2018), “International migration intentions and illegal costs: Evidence using Africa-to-Europe smuggling routes”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13326.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2018), “Global study on smuggling of migrants”, Vienna: UNODC.