With year-on-year inflation rates reaching 10% in 2022, central banks in Europe and the US have been raising interest rates to ensure price stability. These policy decisions involve a delicate balancing of risks to inflation, growth, and financial stability, which have featured prominently in the surrounding debates (Acharya and Rajan 2022, Ball, et al. 2022, Baba and Lee 2022, The Economist 2022). But while we know a lot about the effects on the business cycle, much less is known about the risks to financial stability.

In a recent paper (Jiménez et al. 2022), we study the link between the path of monetary policy and financial crises. We analyse how prolonged interest rate cuts, and subsequent rate increases, affect crisis risk and how the two interact with each other. To do this, we utilise two different sources of data. The first is a historical macroeconomic dataset covering many crises and monetary policy cycles, provided by Jordà et al. (2016). We use these data to attain a bird’s-eye view of the behaviour of monetary policy rates around historical crises, and study the underlying mechanisms linking policy actions to crises through booms and busts in financial markets. The second is an administrative dataset covering the universe of new bank loans to businesses and their defaults in Spain since 1995, provided by Banco de España. We use these data to study how the recent monetary policy cycle in Spain interacted with defaults at the individual loan level, and exploit the differences in responses across firms and banks to shed more light on the mechanisms linking monetary policy dynamics to financial stability.

Before crises, monetary policy rates follow a U shape

We start by documenting the full path of monetary policy rates around historical crisis events. Our analysis shows that pre-crisis monetary policy follows a very specific interest rate path: the U shape.

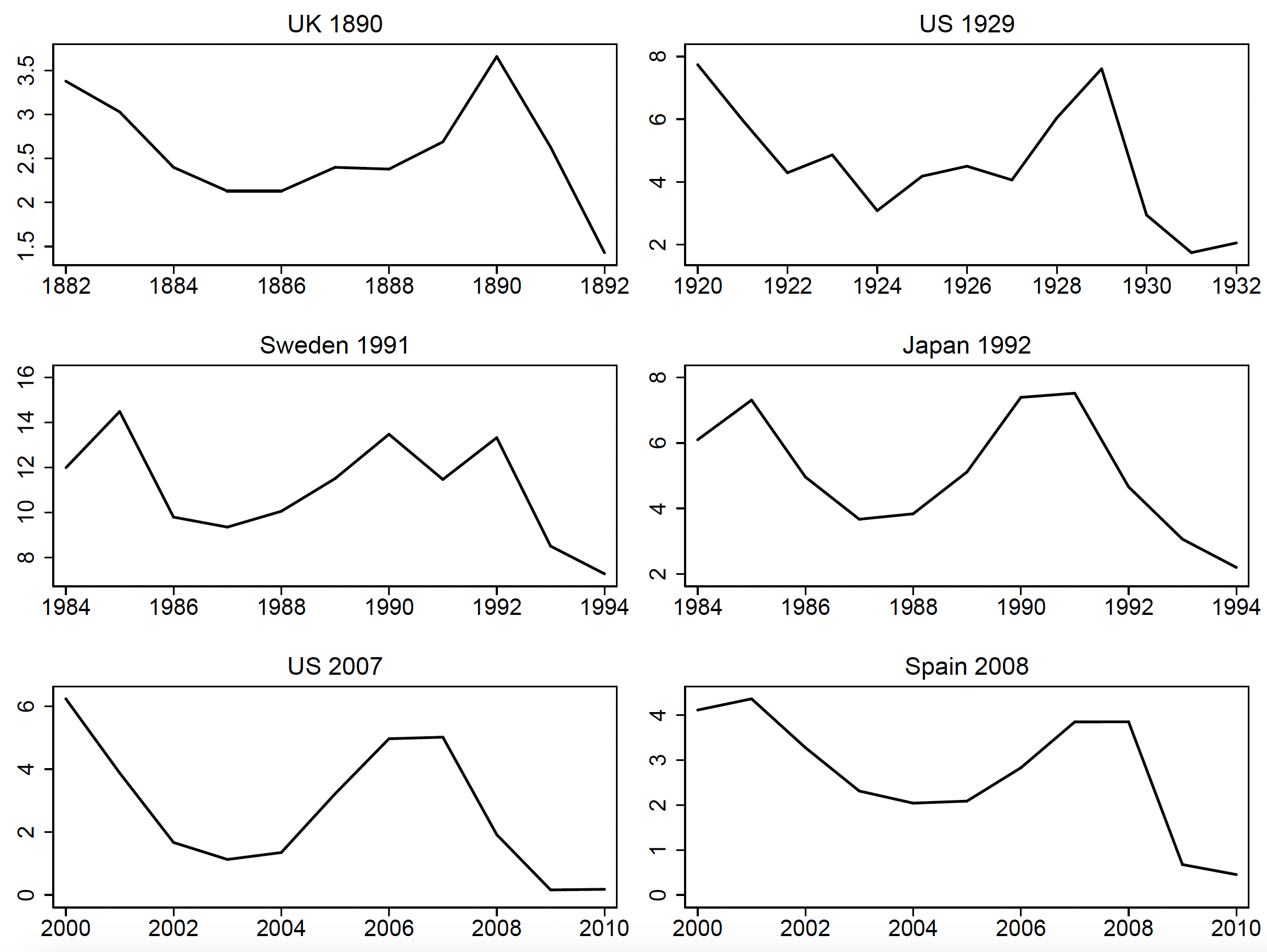

To get a first sense of this, Figure 1 shows the path of monetary policy rates around six important historical financial crises. These include the two largest global crises in our sample: the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-09 (shown for the US and Spain), and the Great Depression (shown for the US). They also include more regional crises such as the Scandinavian and Japanese crises of the 1990s, and the 1890s Baring crisis in the UK. In each of these historical episodes, we observe a U shape to interest rates in the eight years before the crisis, with rates first cut and then increased as the crisis approaches.

Figure 1 Many important historical crises were preceded by a U shape in monetary policy rates

Notes: This figure shows the level of the short-term nominal monetary policy rate for the selected country and year. The crisis dates follow Reinhart and Rogoff (2009).

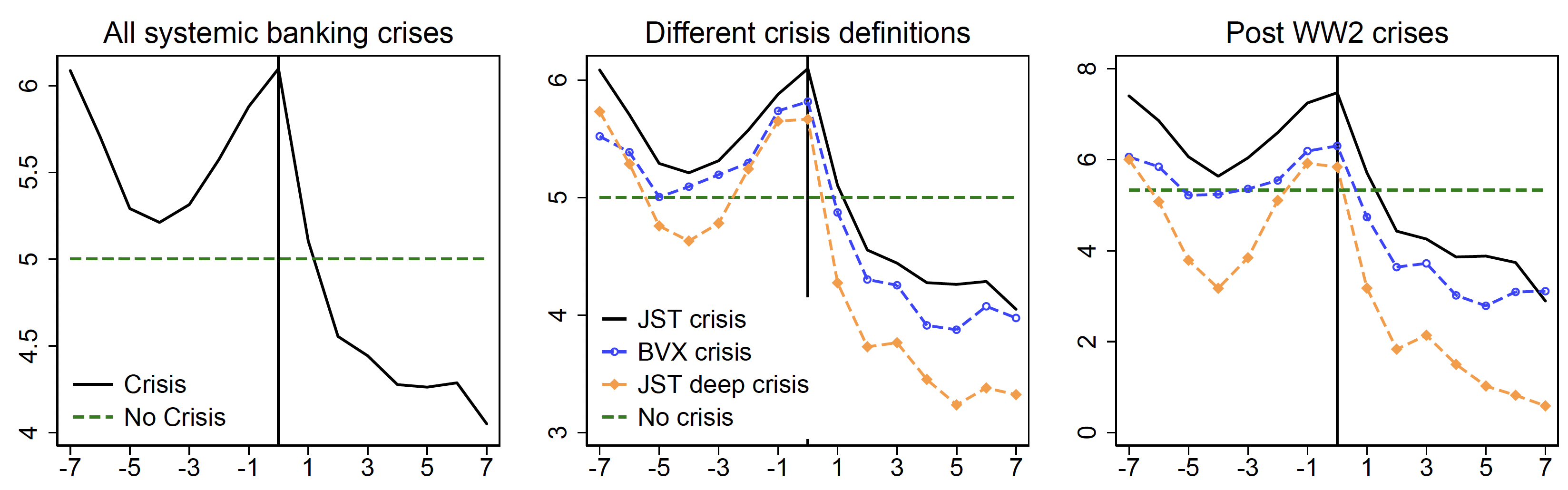

We find that this U-shaped monetary policy is, in fact, a much broader systematic pattern that goes beyond the specific case studies shown in Figure 1. In Figure 2, we plot the average level of monetary policy interest rates before and after a financial crisis for a sample of 72 historical banking crises (24 of these after WWII). Again, we see the same U-shaped pattern, with rates first cut and then increased in the run-up. We observe this pattern across different crisis definitions, and observe a stronger (deeper) U for severe crises, and for crises that started after 1945.

Figure 2 On average, banking crises are preceded by U-shaped monetary policy

Notes: This figure shows the average level of the monetary policy interest rate in year t (start of the crisis at t=0). Total of 72 crises (24 post-WII). The left-hand panel uses the narrative crisis definition from Jordà (2016) (“JST crises”). The middle and right-hand panels additionally show the averages for the Baron et al. (2021) crisis chronology (“BVX crises”) based on bank equity returns, and JST deep crises defined as JST banking crises with -3% or less GDP growth in one year, or average -1% or less GDP growth over 3 years in the t-1 to t+3 window around crisis start, for the full sample (middle panel) and the post-1945 sample (right-hand panel).

The U shape in nominal interest rates is a robust feature of pre-crisis monetary policy. Interestingly, we do not find the same clear and robust patterns for inflation or real interest rates (nominal rates minus inflation). The patterns are also much weaker when it comes to long-term interest rates and non-crisis recessions. This means that the U shape is something specific to short-term nominal policy rates, and to financial crisis risk.

U-shaped monetary policy increases crisis risk

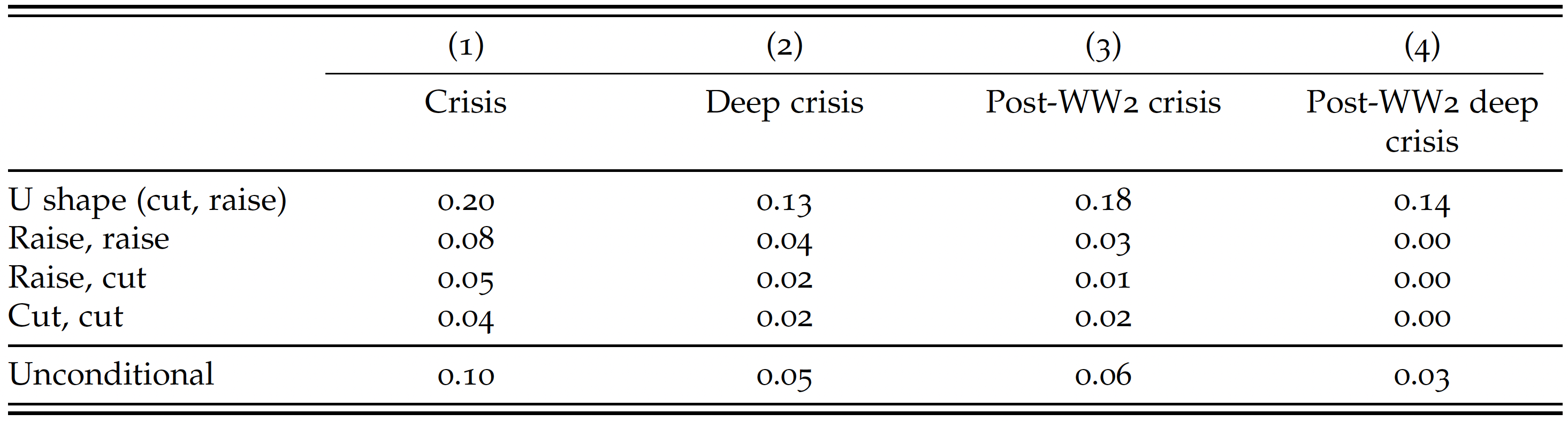

We can also ask the question the other way around: does U-shaped monetary policy increase the likelihood of a financial crisis in the future? We find that it unambiguously does. Table 1 provides a general intuition for this finding. In this table, we calculate the crisis frequency after a U shape in monetary policy rates in the top row, and compare it to crisis frequencies for other monetary policy dynamics (shapes), as well as the average probability of a crisis in the historical data.

Table 1 Crises are much more likely after U-shaped monetary policy rates

Notes: This table reports the frequency of systemic banking crises starting between years t and t+2 for different paths of nominal monetary policy rates between t-8 and t. Crises are dated using the Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor (2016) chronology. Deep crisis is a crisis accompanied by at least -3% GDP growth in 1 year, or -1% average growth over 3 years in the window t-1 to t+3 around the crisis start date. Post-WWII crises are those which started after 1945. In rows, the 4 bins are defined by the sign of the change (cut or raise) in the nominal policy rate between t-8 and t-3 and the sign of the change (cut or raise) between t-3 and t. For example, the U shape (cut, raise) refers to a cut in rates between t-8 and t-3, and a subsequent raise between t-3 and t.

We find that the U-shaped monetary policy rate path is associated with more than twice the crisis risk, compared to other policy rate paths and raw historical averages. For example, the top row of Table 1 shows that after a U shape in monetary policy rates over an eight-year period, the probability of having a crisis over the next three years is 20%. For other monetary policy paths, this probability is below 10%. Importantly, column 4 of Table 1 further shows that for our sample of 17 developed countries, every single deep financial crisis after WWII was preceded by a U shape in monetary policy.

We also test this hypothesis more systematically by applying the standard crisis prediction framework used in previous studies (e.g. Schularick et al. 2021) to our research question. We show that raising interest rates materially increases crisis risk, but only if rates were previously cut. Obviously, in these macroeconomic data, many things are happening at the same time, and it is difficult to tell whether the U shape in rates is really causing the crisis. To help us get around this issue, we use an instrumental variable approach from Jordà et al. (2020), and focus only on those policy rate changes that were mandated by the need to maintain a fixed exchange rate peg (for example, Spain raising rates in response to the Bundesbank to maintain a peg to the Deutsche mark). We find that our results hold, and even become stronger when using this ‘monetary policy trilemma’ instrument.

Rate cuts lead to a financial boom, subsequent rate increases trigger a large financial adjustment

Why is U-shaped monetary policy associated with crises? The narratives of past crisis events often claim that the initial rate cut fosters a boom in lending and asset prices, sowing the seeds of the crisis (e.g. Taylor 2013). The subsequent rate increase in this environment of financial vulnerability then sees these financial booms reverse, and triggers the crisis. We find that a similar sequence of events holds in our historical and administrative data.

First, we show that, in line with previous studies, rate cuts lead to increases in lending and asset prices. Then, we show that if rates are raised after a sequence of cuts, this leads to unusually large credit and asset price declines. Another way of looking at this is by using the concept of the financial ‘red zone’ developed by Greenwood et al. (2022). These authors define the economy to be in a red zone when both credit and asset price growth is high, and they show that being in the red zone significantly increases crisis risk. In our paper, we link both the entry into the red zone and the subsequent crisis to monetary policy actions. We show that rate cuts increase the probability of an economy ending up in the ‘red zone’ and that, once in the ‘red zone’, raising rates leads to unusually large increases in crisis risk.

We then turn to administrative data from the Spanish credit register to further understand these empirical regularities. The Spanish crisis of the early 2000s (shown in Figure 1) provides a perfect laboratory for our studies. First, monetary policy in Spain was largely unrelated to financial developments within the country as interest rates were set in Frankfurt and not in Madrid. Before the euro area sovereign debt crisis of 2010-11, these interest rates largely followed the developments in core euro area countries. Second, the detailed administrative data allow us to explore how these monetary policy actions affected the riskiness of different types of loans made by different banks, helping us better understand the drivers of the stylised patterns in the historical data. Mirroring the setup in the aggregate long-run data, we focus on the default probabilities of individual loans that were issued after a period of monetary loosening, when interest rates start increasing.

The findings from the administrative data validate our historical analysis. We first show that loans granted during periods of monetary policy loosening are around 16.1% more likely to default (relative to an average default probability of 1.9 percentage points) than loans which were granted when monetary policy was tighter. We then show that increasing rates during the lifetime of the loan also increases default risk, with a 1 percentage point increase in the policy rate in the year after loan origination raising the probability of loan default by 14.4%. Finally, adding the interaction of the two, we find that loans granted during periods of monetary loosening are especially vulnerable to default risk when monetary policy is tightened. For a loan granted during a period of loose monetary policy, default probability increases by 28.4% when rates are increased by 1 percentage point.

The loan-level data also provide strong evidence in favour of one specific mechanism for these findings: banks’ risk taking. We find that the effects of U-shaped policy on loan default risk are much stronger for ex ante riskier firms (especially those with a bad credit history) and for banks with weaker balance sheets (i.e. high levels of non-performing loans, or NPLs). For instance, going from the 25th to 75th percentile of the NPL ratio distribution increases the likelihood of default after U-shaped monetary policy by 82%. This suggests that especially weaker banks engage in risky lending when rates are cut, and raising rates leads to more defaults on these riskier loans.

Conclusions and policy discussion

Our results, both with historical and administrative data, show that U-shaped monetary policy entails substantial risks for financial stability. A cut in monetary policy rates over several years followed by a 1 percentage point increase in rates more than doubles the risk of a banking crisis, and materially increases the risk of default on individual loans.

The implications of our analysis for monetary policy are, however, subtle. Broadly speaking, our findings imply that the impact of today’s monetary policy on financial stability is significantly affected by monetary policy actions in the past. For example, in a macroeconomic environment like today, using monetary policy to reduce inflation is likely to increase financial instability. We show that if policy rates have been cut over a prolonged period of time, allowing financial vulnerabilities to build up, raising rates is more likely to crystallise these vulnerabilities and trigger a financial crisis, rather than prevent it. When it comes to deflating financial booms more generally, our findings suggest that it is important to act as early as possible, and not allow the country to end up in a vulnerable financial ‘red zone’

References

Acharya, V V and R G Rajan (2022), “Where Has All the Liquidity Gone?” Project Syndicate, 7 October 7.

Baba, C and J Lee (2022), “High inflation would amplify second-round effects but need not prolong them”, VoxEU.org, 16 September.

Ball, L, D Leigh and P Mishra (2022), “Understanding US Inflation in the COVID Era”, VoxEU.org, 22 November.

Baron, M, E Verner and W Xiong (2021) “Banking crises without panics”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(1): 51-113.

The Economist (2022), “Investing in an Era of Higher Interest Rates and Scarcer Capital”, 8 December.

Greenwood, R, S G Hanson, A Shleifer, and J A Sørensen (2020), "Predictable Financial Crises", VoxEU.org, 15 July.

Jiménez, G, D Kuvshinov, J L Peydró and B Richter (2022), “Monetary policy, inflation, and crises: New evidence from history and administrative data”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17761.

Jordà, Ò, M Schularick and A M Taylor (2016), “Macrofinancial history and the new business cycle facts”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 31(1): 213-263.

Jordà, O, M Schularick and A M Taylor (2020), "The effects of quasi-random monetary experiments", Journal of Monetary Economics 112: 22-40.

Reinhart, C M and K S Rogoff (2009), This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton University Press.

Schularick, M, L ter Steege and F Ward (2020), “‘Leaning against the wind’ and the risk of financial crises”, VoxEU.org, 12 January.

Taylor, J B (2013), Getting off track: How government actions and interventions caused, prolonged, and worsened the financial crisis, Hoover Press.