Over the last decade, between 30% and 35% of PhDs in economics in the US were earned by women; yet, in 2019, only 14.5% of full professors were women (CSWEP 2017, 2019). This phenomenon, labeled the ‘leaky pipeline’, sees women exhibit higher attrition compared to men when moving along their career paths. While the phenomenon is present in many realms, the puzzling persistence of the leaky pipeline in US and UK economics departments has made headlines and attracted research. The underrepresentation of women in the economics profession has prompted several economic societies, organisations, and committees to take action (Ray and Weder di Mauro 2019). The leaky pipeline has been documented in the US (Lundberg and Stearns 2019), the UK (Gamage et al. 2021), and Germany (Friebel et al. 2021), to name only a few examples. Economics scores low on diversity generally (Sharpe 2020), and with regard to gender, economics scores even worse than other STEM fields (Ginther and Khan 2014). What are the possible reasons for the gender gap in economics?

The literature identifies several determinants, many of which reflect an unproductive and unfriendly culture. Women face discrimination in professional and non-professional occasions, and are treated differently when publishing, co-authoring, and going through the hiring process. Whether the situation of women in academic economics differs across countries and regions due to taste, norms, and policies more favorable to women is an empirical issue that we explore in Auriol et al. (2022). We use the same standardised approach based on a web-scraping algorithm for institutions across the world. When accessing the institutions’ websites, the algorithm collects information on the individuals listed (e.g. name or position). Each individual gets assigned a gender and position level. Since these descriptions vary across countries owing to different languages, we classify more than 1,000 position titles into a generally accepted hierarchy of positions to make comparability across countries as accurate as possible: (full) professor, associate professor, assistant professor, lecturer, research fellow, and research associate.

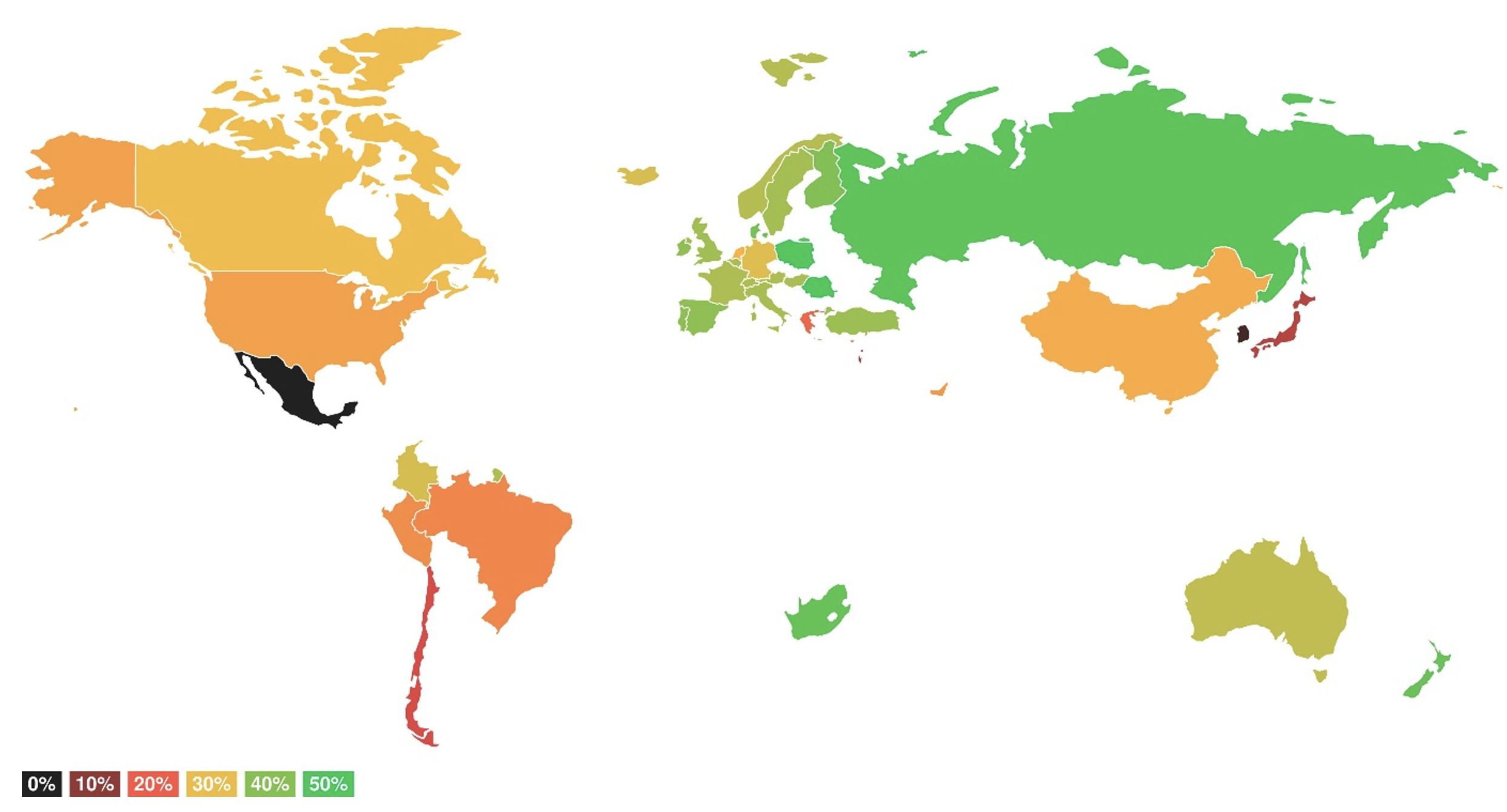

Figure 1 Share of women at all academic levels

Note: Proportion of women in all academic positions (full database). This figure plots information on all positions in the full database as of December 2020. Countries for which we have no observations in our database are left blank. For the following countries, we have only observations on one institution in the database: Colombia, Cyprus, Liechtenstein, Mexico, and United Arab Emirates.

What do our data reveal? Australia and New Zealand have around 35% women at all academic levels, Europe around 32%, and North America only 26%. Figure 1 clearly shows the heterogeneity across countries and regions: Europe seems to be more gender-equal than North America. When looking at the top 300 research institutions worldwide – covering 238 universities and business schools (82 in the US and 122 in Europe) but also central banks or other research organisations – we find that more than half of them are in Europe, which makes the European market for economists of similar importance to the North American market. Focusing on universities and business schools, women hold 20% of senior-level positions (full professor, associate professor) and 32% of junior-level positions in the 82 US institutions; in the 122 European institutions, the numbers are 27% and 38%, respectively. These differences between countries and regions confirm that Europe is more gender equal than the US. Overall, US research institutions have almost seven percentage points fewer women than European institutions. The US- market is also more homogeneous than Europe’s since the share of women occupying all levels, the senior level, and the entry level, is very similar across states. This is in sharp contrast to the European market, which is very heterogeneous region-wise and country-wise. Within Europe, the Nordic countries and France have higher shares of women than Germany and the Netherlands.

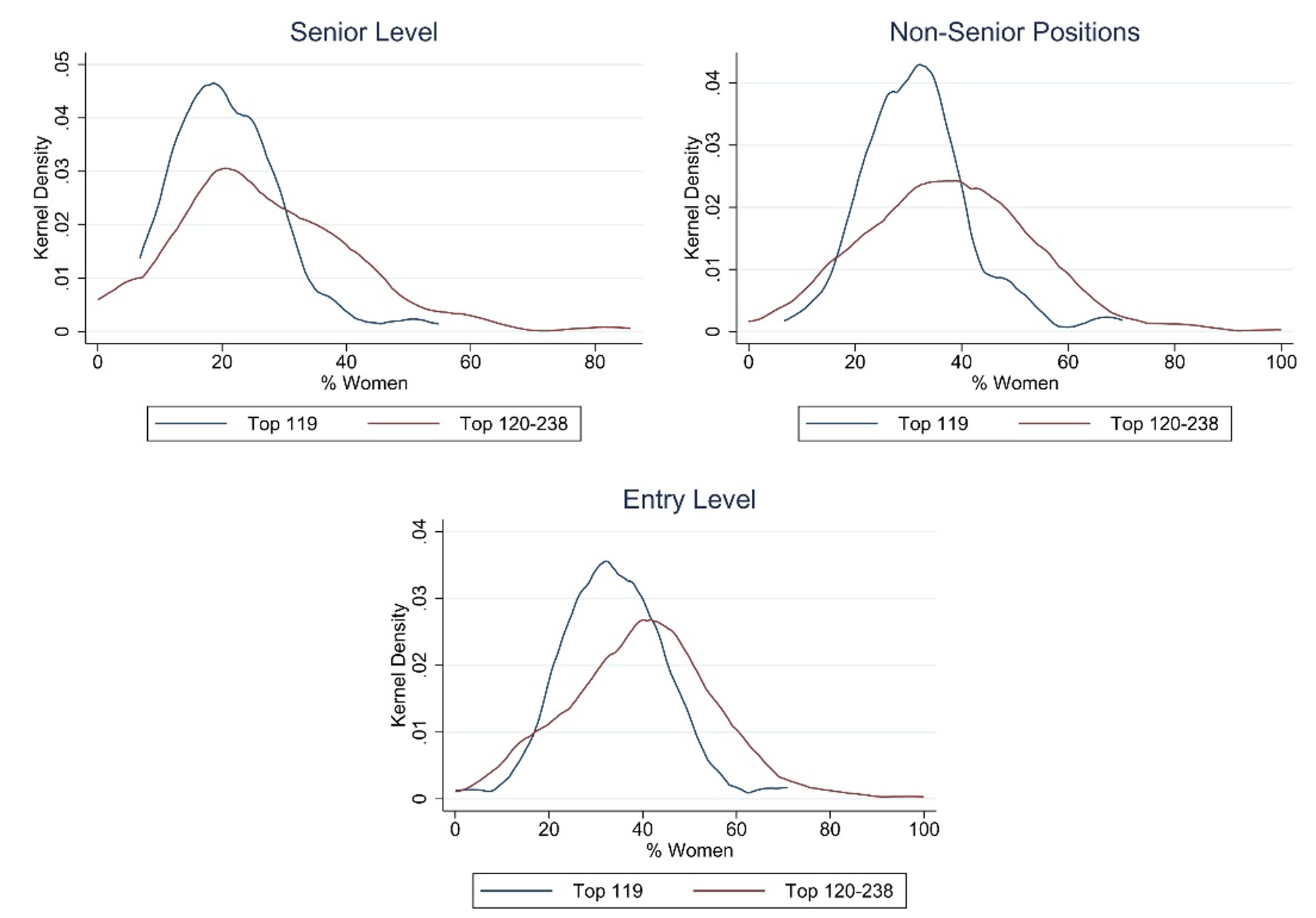

The numbers also show that the highest-ranking institutions (in terms of research output in RePEc) have fewer women in senior positions, and the point estimates are higher in the US: an institution ranked 100 places higher has about three percentage points fewer women in Europe, but it increases to nearly five percentage points in the US. While the usual explanation for the lack of women in senior positions is the leaky pipeline hypothesis, we would not expect this to matter at the junior level, where research potential should be the main factor and there is no reason to believe that women’s potential is less than men’s. At the junior level in the US, there is a surprising three percentage-point decrease in the share of women if an institution is ranked 100 places higher. The entry-level effect does not occur in Europe. The leaky pipeline may therefore begin earlier than often assumed (as illustrated in Figure 2) and is even more of an issue in the highly integrated market of the US.

Figure 2 Kernel density estimates by level

To sum up, country comparisons reveal that Europe scores higher in terms of gender equality than the US. Ranking effects are also stronger in the US than in Europe, and the top institutions in the US have higher standards for female faculty at the entry level: attrition occurs not just prior to reaching senior positions, but right after the completion of the PhD. The question thus arises: what could explain these regional effects?

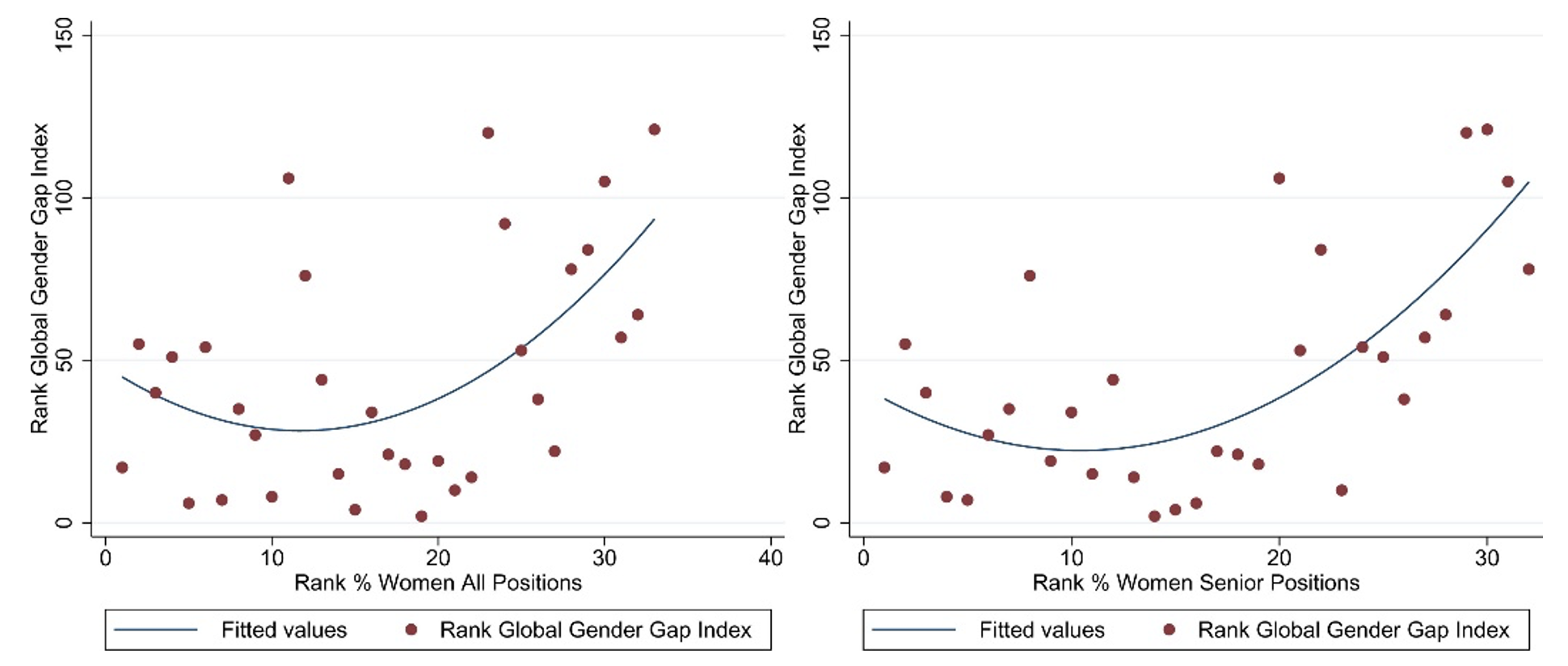

Cultural differences affecting hiring and the academic job market might play a role here. The substantial heterogeneity across countries and regions in Europe and between Canada and the US may be driven by gender norms or policies, or by other country-specific institutions. As illustrated in Figure 3, the observed heterogeneity correlates with broader measures of gender equality in the respective country. Combining these findings with results from the latest waves of the World Values Survey shows deeply rooted perceptions of gender roles and gender equality. For instance, less than 5% of respondents in Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark (strongly) agree with the statement “University is more important for a boy than for a girl”. This figure is 6% in France and around 4% in the UK, but almost 10% in the US.

Figure 3 Correlation between gender gap index and share of women

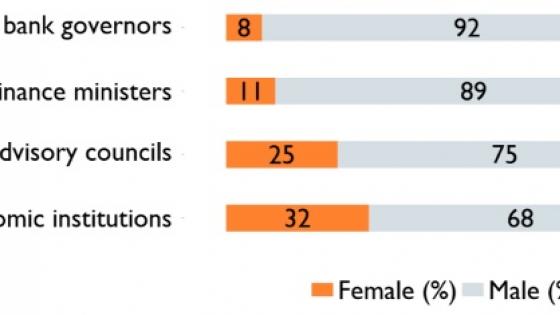

The lack of women in academic settings already makes itself seen at schools or universities (Advani et al. 2019). Even after graduation, reference letters for female and male economists are written differently, impacting the trajectories of their academic careers (Baltrunaite et al. 2022). Beyond fairness concerns, there are many other reasons to care about the facts documented in our research. First, if positions are mainly filled from the male ability distribution, more capable women are neglected, and universities forego the opportunity to hire or retain more capable employees. Further, increasing diversity leads to other benefits since women and men research in different fields and have different views on policy (Megalokonomou et al. 2021, Masciandaro et al. 2018). Second, more successful women would draw added capable women into the field. Third, women choose different research topics than men. The weak representation of women in the most prestigious and powerful positions implies fewer resources dedicated to these topics and less publicity around the results. This would mean that economics systematically underinvests in some socially relevant topics. Further, the underrepresentation of women in economics also extends to the public and private sector (Hanspach et al. 2021).

In more general terms, we believe that the method used in our research can contribute to a more informed discussion about diversity in general, and gender in particular, in a multitude of academic disciplines and industries. Web-scraping overcomes the response bias to which surveys are subject. The cooperation of many universities, research institutes, and business schools has been crucial for our work, and we hope that other types of organisations would be equally cooperative.

References

Advani, A, R Griffith and S Smith (2019), “Increasing Diversity in Economics”, VoxEU.org, 16 October.

Auriol, E, G Friebel, A Weinberger and S Wilhelm (2022), “Underrepresentation of women in the economics profession more pronounced in the United States compared to heterogeneous Europe”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119, e2118853119.

Baltrunaite, A, A Casarico and L Rizzica (2022), “Gendered references and career success in the economics profession”, VoxEU.org, 3 October.

CSWEP (2017), The 2017 Report on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession, Annual Report.

CSWEP (2019), The 2019 Report on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession, Annual Report.

Friebel, G, N Fuchs-Schündeln and A Weinberger (2021), “Statusbericht zum Frauenanteil in der Volkswirtschaftslehre an deutschen Universitäten”, Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik 22: 142–155.

Gamage, D D K, A Sevilla and S Smith (2021), “Women in economics: a UK perspective”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36: 962–982.

Ginther, D and S Khan (2014), “Women in Economics: Moving Up or Falling Off the Academic Career Ladder?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 18: 193–213.

Hanspach, P, J Palka and V Sondergeld (2021), “Few top positions in economics are held by women”, VoxEU.org, 15 February.

Lundberg, S and J Stearns (2019), “Women in Economics: Stalled Progress”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 33: 3–22.

Masciandaro, D, P Profeta and D Romelli (2018), “Why women matter in monetary policymaking”, VoxEU.org, 25 September.

Megalokonomou, R, M Vidal-Fernandez and D Yengin (2021), “Why having more women/diverse economists benefits us all”, VoxEU.org, 11 November.

Rey, H and B Weder di Mauro (2019), “Announcing the Women in Economics CEPR Initiative”, VoxEU.org, 10 April.

Sharpe, R V (2020), “Black women economists: At the intersection of race and gender”, in Women in Economics, CEPR Press, 31–35.