The Global Crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis have shown how consequential shifts in market sentiment can be. Indeed, it is a widely held view that financial crises have an important self-fulfilling component, driven by market sentiment and beliefs (Goldstein and Razin 2013). Therefore, improving our understanding of the role of beliefs is crucial to prevent future crises, and to better respond to them when they do occur. In this column, we give an overview over the vast literature on beliefs and uncertainty, discuss their measurability and, for the first time, establish some stylised facts for some indicators of market sentiment in a large panel of advanced countries.

The possible transmission channels

At an intuitive level, economists and non-economists alike find it plausible that economic sentiment and economic developments are related – and indeed some measures of sentiment are tightly correlated with the business cycle (more on this below). Beliefs about the future may both drive, and be driven by, subsequent economic trends. However, the existence of a correlation does not necessarily shed light on the underlying transmission mechanisms and shocks. In a recent paper, we survey this literature in greater detail, and try to derive some general lessons that may be useful for policymakers (Nowzohour and Stracca 2017).

There are three main – not necessarily exclusive – ways to think about the role of sentiment in the business cycle.

- Irrational animal spirits advocates (dating back to Keynes 1936, but more recently Akerlof and Shiller 2010, De Grauwe and Ji 2016) see the cause of macroeconomic fluctuations in purely psychological waves of optimism and pessimism, often driven by random shocks (‘sunspots’). This implies that any expansion driven by animal spirits must eventually lead to a bust, as fundamentals remain unaffected. Hence, beliefs only drive the economy in the short term, although these short-term effects may be made more persistent by hysteresis and other internal propagation mechanisms.

- Self-fulfilling animal spirits advocates (e.g. Cass and Shell 1983, Farmer 1999, Farmer 2012b, Farmer 2012c, Farmer 2013, Acharya et al. 2017a, Benhabib et al. 2016, Bacchetta and Van Wincoop 2013) also see the root of macroeconomic fluctuations in animal spirits, but believe that precisely the actions following these lead to changes in fundamentals, making the initial boom or bust in confidence both rational and self-fulfilling. An important distinction in the class of endogenous business cycle models that has developed since then is made in Farmer and Serletis (2016) between dynamic and steady-state indeterminacy. In the former case, sunspots cause small fluctuations around a unique steady state, while in the latter, sunspots move the economy to a new equilibrium that may be a long way from any notion of a desirable one. Shiller (2017) emphasises the role of narratives and social interactions as drivers of shared beliefs, which then have material consequences for the economy.

- News advocates (e.g. Beaudry and Portier 2014, Beaudry and Portier 2006, Barsky and Sims 2012, Blanchard et al. 2013), on the other hand, believe that agents have access to a non-measurable source of imperfect information about future developments of the economy. Changes in beliefs are not driven by psychology or random beliefs, but by an optimal processing of available information. In this view, the economy is subject to recurrent booms (if the signal was correct) and occasional busts (if the signal was false).

What is the nexus between confidence and uncertainty?

Market sentiment could be thought of as a combination of confidence and uncertainty. Confidence can be defined as a strong belief in positive future economic developments, which, as just discussed, may be the result of animal spirits and/or news about future economic developments. Uncertainty could be either the range of possible outcomes of future economic developments, and/or the lack of knowledge of the probability distribution from which future economic developments are drawn. The interaction and respective importance of the three concepts for overall sentiment is far from trivial, as they may be observationally equivalent. At least in theory, however, a distinction can be made.

When the range of possible outcomes is large, agents feel uncertain about their expected outcome (i.e. the mean of the distribution of potential outcomes), and are therefore less confident in their actions reflecting their expectations of future economic developments. For example, in a macroeconomic model with standard preferences, if agents expect their income to grow in the future with certainty, they would consume more today in anticipation of their increased budget tomorrow in order to smooth consumption. However, if their belief was subject to large uncertainty (i.e. if the range of possible outcomes of income growth is wide), agents may increase their consumption by much less, and instead pile up precautionary savings.

Moreover, it has been shown that agents tend to be ‘ambiguity averse’ – they prefer an event whose odds are well known to another one where they are not. Related, in the absence of a clear model guiding their economic choices, agents are more likely to follow the crowd in the belief that others may have more reliable information about the economy. As a result, the economy can shift between extreme volatility and excessive stability for no apparent reason.

How do we measure economic sentiment?

The empirical literature on uncertainty has proposed a variety of ways to measure uncertainty and systemic risk; for example, based on forecast densities (Rossi et al. 2016), forecast disagreement and ex post forecast errors (Bachmann et al. 2013), VaR measures with varying underlying return distributions (Allen et al. 2012), financial institutions’ VaR given that other financial institutions are in financial distress (Adrian and Brunnermeier 2016), and financial institutions’ expected capital shortfalls given that a crisis occurs (Brownlees and Engle 2016, Acharya et al. 2017b). We survey this literature in greater detail in our paper.1

We select some common and easily accessible indicators that are available at monthly frequency and with broad country coverage to measure different aspects of market sentiment:

- Stock market volatility, which measures financial-market-based uncertainty;

- Survey-based consumer confidence, which measures confidence as perceived by households;

- Economic policy uncertainty (EPU), which measures the uncertainty of the ‘rules of the game’; and

- Their first principal component, which measures their common variation (shown to account for a majority of the total variation).

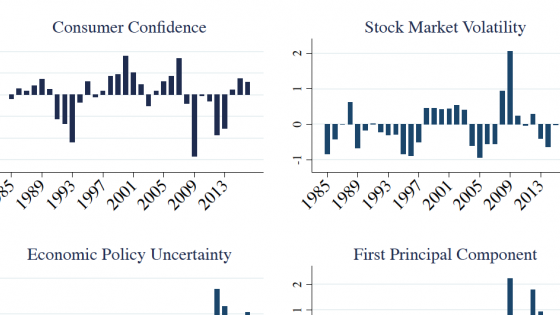

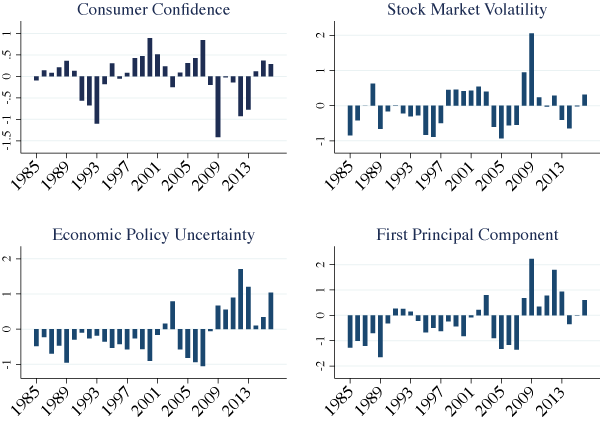

Figure 1 shows the indicators as annual cross-country averages for our panel of 27 advanced economies between January 1985 and October 2016.

Figure 1 Market sentiment measures

Sources: Baker et al. (2016), Datastream/CBOE, and authors’ calculation. Note: series are annual cross-country averages.

Some new stylised facts for a panel of countries

Using these data and some more specific consumer survey indicators and subcomponents, as well as absolute negative stock returns and skewness of stock returns, we establish some new stylised facts.

- First, market sentiment measures are relatively lowly correlated on a country level.

We computed pairwise correlation coefficients of our sentiment proxies as the average of their correlations on a country level.

Notably, the stock market variables are only lowly correlated with the consumer expectations variables, however, with the expected negative sign for stock market volatility and absolute negative stock returns. Most strikingly, stock market volatility and absolute negative stock returns are almost perfectly co-linear, indicating that stock market volatility essentially represents realised downside risk.

The indicator of EPU is, on average, negatively correlated with consumer confidence. However, our estimate of -0.37 is in absolute terms considerably lower than the correlation Baker et al. (2016) find between EPU and the Michigan Consumer Sentiment index of -0.74, indicating that the link between EPU and consumer confidence is higher in the US than in other advanced economies in our sample. Economic policy uncertainty is also slightly less positively correlated with stock market volatility (0.33) than what Baker et al. (2016) find between EPU and the VIX (0.58).

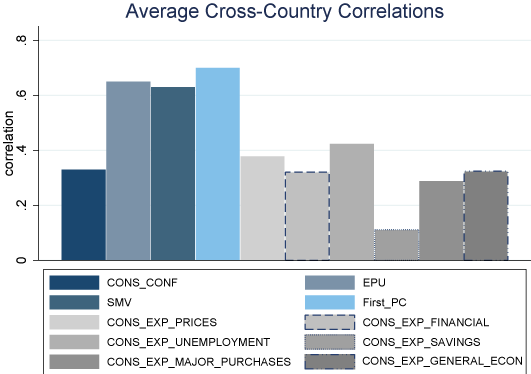

- Second, sentiment measures are relatively highly correlated across countries, especially for stock market volatility and economic policy uncertainty.

While consumer confidence has an average cross-country correlation of only 0.33, Economic policy uncertainty and stock market volatility show somewhat higher correlations of 0.65 and 0.63, respectively. The cross-country correlation of the first principal component of all three indicators (0.7) suggests that the latent common variation in market sentiment proxies exhibits stronger cross-country co-movement than the underlying market sentiment proxies themselves.

Figure 2 Average cross-country correlation of sentiment proxies

Notes: Monthly data, 1985-2016, 27 countries.

- Third, consumer confidence seems to have the closest co-movement with economic and financial variables, and most of the correlations are contemporaneous or forward-looking, consistent with the view that sentiment is a driver of the business cycle.2

We estimate cross correlations of macroeconomic and financial variables, as well as sentiment proxies, by regressing one macro variable3 at a time on monthly leads and lags (both up to 12) of our sentiment measures, consumer confidence, stock market volatility, EPU, and their first principal component, using monthly data for up to 27 countries in the sample period 1985–2016 (or longest available), and also including time and country fixed effects.

From the point of view of consumer confidence, most coefficients peak either contemporaneously or ahead of economic developments, while they tend to be lower when lagging economic developments. The coefficients for stock market volatility and EPU are generally surrounded by more uncertainty. Stock market volatility is largely the mirror image of consumer confidence, but the correlations with macro variables are generally less tight and economic policy uncertainty has the lowest and least consistent correlations with macroeconomic and financial variables. Looking at the common factor, which can be interpreted as an overall measure of (weak) economic sentiment or uncertainty, we find that its correlations are largely the mirror image of those of consumer confidence. Again, the peak correlations are either contemporaneous or forward-looking.

Conclusions

The idea that beliefs and psychological factors drive the business cycle is not new, but it has received new impetus from the Global Crisis and the instability experienced in the past decade. In this column, we have reviewed what the literature has to say on the possible transmission channels, as well as a set of three stylised facts for some popular indicators of economic sentiment, confidence, and uncertainty. Clearly, understanding the role of sentiment remains a challenge, which should occupy economists and policymakers for years to come.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and are not necessarily shared by the institutions to which they are affiliated.

References

Acharya, S, J Benhabib and Z Huo (2017a), “The anatomy of sentiment-driven fluctuations”, NBER.

Acharya, V V, L H Pedersen, T Philippon and M Richardson (2017b), “Measuring systemic risk”, Review of Financial Studies 30(1): 2–47.

Adrian, T and M K Brunnermeier (2016), “Covar”, American Economic Review 106(7): 1705–1741.

Akerlof, G A and R J Shiller (2010), Animal spirits: How human psychology drives the economy, and why it matters for global capitalism, Princeton University Press.

Allen, L, T G Bali and Y Tang (2012), “Does systemic risk in the financial sector predict future economic downturns?”, Review of Financial Studies 25(10): 3000–3036.

Bacchetta, P and E Van Wincoop (2013), “Sudden spikes in global risk”, Journal of International Economics 89(2): 511–521.

Bachmann, R, S Elstner and E R Sims (2013), “Uncertainty and economic activity: Evidence from business survey data”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5(2): 217–249.

Baker, S R, N Bloom and S J Davis (2016), “Measuring economic policy uncertainty”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4): 1593-1636.

Barsky, R B and E R Sims (2012), “Information, animal spirits, and the meaning of innovations in consumer confidence”, American Economic Review 102(4): 1343–1377.

Beaudry, P and F Portier (2006), “Stock prices, news and economic fluctuations”, American Economic Review 96(4): 1293–1307.

Beaudry, P and F Portier (2014), “News-driven business cycles: Insights and challenges”, Journal of Economic Literature 52(4): 993–1074.

Benhabib, J, X Liu and P Wang (2016), “Feelings, financial markets, and macroeconomic fluctuations”, Journal of Financial Economics 120(2): 420-443.

Benigno, G and L Fornaro (2017), “Stagnation traps”, Review of Economic Studies, Forthcoming.

Blanchard, O J, J–P L’Huillier and G Lorenzoni (2013), “News, noise, and fluctuations: An empirical exploration”, American Economic Review 103(7): 3045–3070.

Brownlees, C and R F Engle (2016), “Srisk: A conditional capital shortfall measure of systemic risk”, Review of Financial Studies 30(1): 48–79.

Cass, D and K Shell (1983), “Do sunspots matter?”, Journal of Political Economy 91(2): 193–227.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2016), “Animal spirits and the international transmission of business cycles”, Technical report, CESifo Group Munich.

ECB (January 2013), “Confidence indicators and economic developments”, Monthly Bulletin.

Farmer, R E (1999), The macroeconomics of self-fulfilling prophecies, MIT Press.

Farmer, R E (2012b), “Confidence, crashes and animal spirits”, Economic Journal 122(559): 155–172.

Farmer, R E (2012c), “The stock market crash of 2008 caused the great recession: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 36(5): 693–707.

Farmer, R E (2013), “Animal spirits, financial crises and persistent unemployment”, Economic Journal 123(568): 317–340.

Farmer, R E and A Serletis (2016), “The evolution of endogenous business cycles”, Macroeconomic Dynamics 20(2): 544–557.

Goldstein, I and A Razin (2013), “Theories of financial crises”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Keynes, J M (1936), The general theory of interest, employment and money, London: Macmillan.

Nowzohour, L and L Stracca (2017), “More than a feeling: Confidence, uncertainty and macroeconomic fluctuations”, ECB Working Paper No 2100.

Rossi, B, T Sekhposyan and M Soupre (2016), “Understanding the sources of macroeconomic uncertainty”, Available at SSRN.

Shiller, R J (2017), “Narrative economics”, American Economic Review 107(4): 967-1004.

Endnotes

[1] The database underlying the paper is available from the authors upon request.

[2] Note that we are not making causality statements here. Clearly, causality can run both from sentiment to economic activity and the other way around. Moreover, we are not claiming the absence of a third factor driving both sentiment and economic activity. Still, it is useful to see what the evidence suggests in terms of correlation, before moving to a more structural analysis.

[3] Inflation, unemployment, industrial production growth, credit growth, real house price growth, real appreciation, and short-term interest rates.