To what extent do the characteristics of neighbourhoods that children grow up in affect the children’s development and behaviour? Existing studies show that neighbourhoods impact outcomes such as the children’s later earnings and educational attainment (Chetty et al. 2016, Chetty and Hendren 2018, Fatemeh et al. 2019). The impact of neighbourhood crime on teenagers’ development is of particular concern (Deming et al. 2016, Dustmann and Landersø 2018). In a recent paper, we estimate the effect of growing up in neighbourhoods with higher levels of gang crime on criminal behaviour, teenage motherhood, and long-run economic outcomes (Dustmann et al. 2023).

Our analysis exploits a unique natural experiment in Denmark, where refugee families were quasi-randomly allocated to municipalities that varied in their level of gang crime. The same natural experiment has been used to study spillovers in criminal behaviour more generally (Damm and Dustmann 2014) and the impact of refugee migration on electoral outcomes (Dustmann et al. 2019). Detailed conviction records allow us to construct a measure of gang crime. We then estimate the causal effect of assignment to municipalities with higher levels of gang crime on the assignees’ outcomes by comparing the outcomes of children allocated to municipalities with different gang crime rates at the time of their assignment.

Neighbourhood gangs increase the risk of youth crime for boys

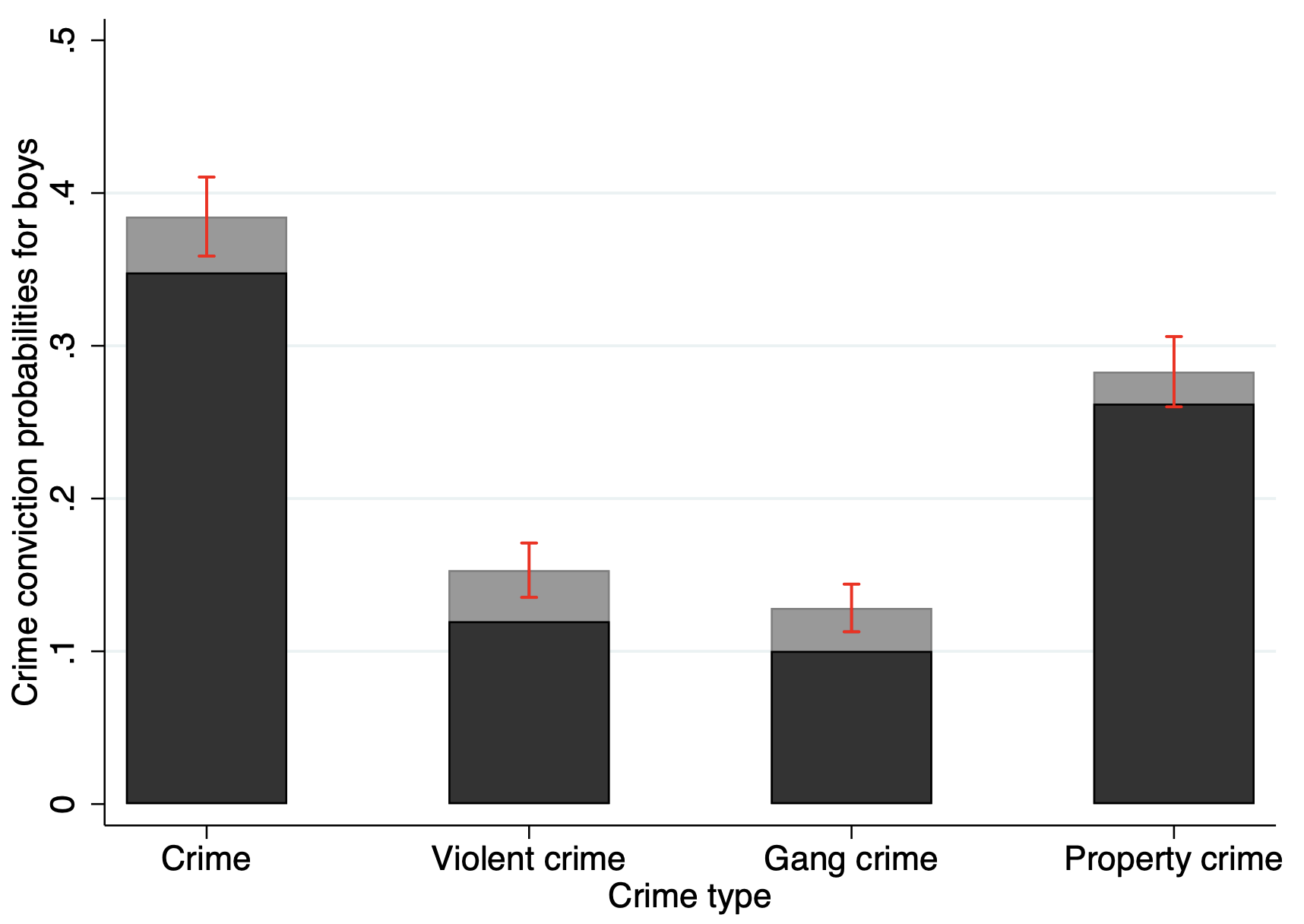

We show that boys assigned before the age of 15 to municipalities with higher levels of gang crime at the time of assignment are more likely to commit a crime between ages 15 and 18. As illustrated in Figure 1, a one-standard-deviation-higher gang crime rate at the time of assignment increases the probability that boys commit any crime between ages 15 and 18 by 3.7 percentage points (10.6%). Figure 1 also shows the effects by crime type: violent crime and gang crime are the most affected, both increasing by approximately 28% with each standard-deviation increase in the gang crime rate at time of assignment.

Figure 1 Crime conviction probabilities and municipality gang crime

Notes: The figure shows (in black) the share of assigned refugee boys who commit at least one crime that leads to a conviction when they are 15–18 years old. The grey bars indicate the increase in crime rates associated with a one-standard-deviation-higher gang crime rate in the municipality of assignment at time of assignment. The vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Our results further show that boys assigned between ages 7 and 14 are most affected. For these boys, assignment to a municipality with a one-standard-deviation-higher gang crime rate increases the probability that they commit any crime between ages 15 and 18 by 17.5%.

Unlike the large effects for boys, we find no evidence that crime in the municipality of assignment at the time of assignment affects the criminal behaviour of girls.

Neighbourhood gangs lead to more teenage mothers

While gang crime has no impact on the criminal behaviour of girls, it leads to an increased probability that they become teenage mothers. This is in line with the hypotheses put forth by Sanders (2011) suggesting that the risky behaviour of girls manifests itself through early motherhood.

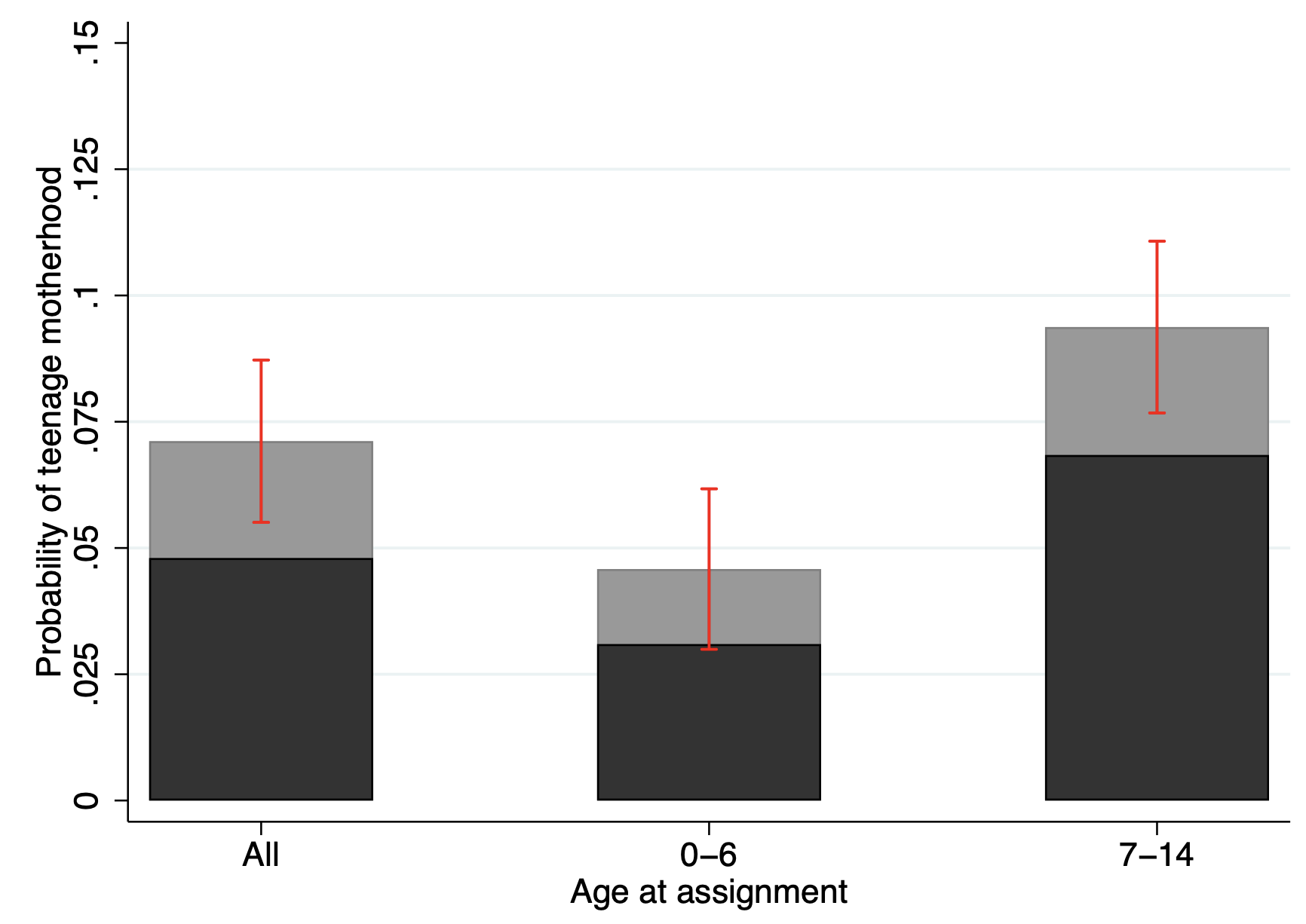

Figure 2 shows that assignment to a municipality with a one-standard-deviation-higher gang crime rate increases the probability that girls become mothers before age 19 by 2.3 percentage points, or around 48%. Like the results on male criminal behaviour, we show that this effect is larger and more precisely estimated for girls who were between 7 and 14 years old at the time of assignment. This is in line with the social sciences literature that points to the age between 6 and 14 as a critical development period, during which children are at an increased risk for neighbourhood-based effects on behaviour (see Ingoldsby and Shaw 2002 for a review).

Figure 2 Teenage motherhood and municipality gang crime

Notes: The figure shows (in black) the mean teenage motherhood rate of assigned refugee girls. The grey bars indicate the increase in teenage motherhood rates associated with a one-standard-deviation-higher gang crime rate in the municipality of assignment at time of assignment. The vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

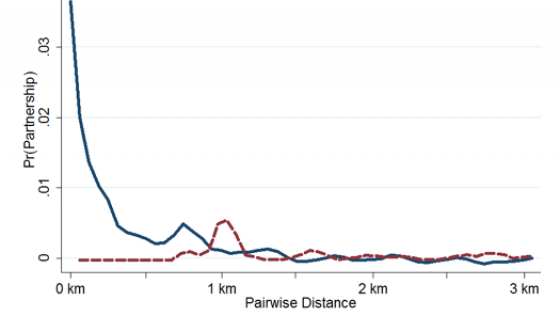

In the paper, we highlight direct social interaction between assigned girls and gang members as one key mechanism by showing that the fathers of children of teenage mothers are more likely to have committed gang crimes than other comparable boys.

Growing up in a neighbourhood with more gangs has detrimental long-run effects on economic outcomes

By impacting the criminal propensity of young men and the teenage motherhood rates of young women, gang crime may also impact young people’s long-run economic outcomes.

Our research shows that being assigned to municipalities with higher gang crime levels decreases the probability that the young men, when they are 19 to 28 years old, are employed or in education. For young women, it lowers levels of earnings and raises levels of benefit claims when they are 19 to 28 years old. Boys assigned to a municipality with a one-standard-deviation-higher gang crime rate spend 8.2% more years as inactive (neither in employment nor education) when they are between 19 and 28 years old, while girls claim 6.5% more welfare benefits over the same period.

Neighbourhood gang crime is far more important than other municipality characteristics

Municipalities vary across many other dimensions than their level of gang crime. Due to the high degree of detail in our data, we are able to compare the influence of other municipality characteristics to that of gang crime. The results clearly point towards crime and more specifically gang crime being the single-most-important neighbourhood characteristic that impacts children’s future outcomes.

Discussion

Our study finds that exposure to gang crime leads to an increased propensity for crime among boys when they are 15 to 18 years old. For girls, we find no effect of exposure to gang crime on their criminal behaviour but find strong evidence that teenage motherhood increases with the level of gang crime in the municipality. Furthermore, we show that exposure to higher levels of gang crime during childhood leads to increased rates of inactivity for men and decreases earnings and increases welfare benefit claims for women. When compared to gang crime, other municipality characteristics appear much less influential.

Our study highlights gang crime as a particularly detrimental neighbourhood characteristic that results in higher crime rates among young men, higher teenage pregnancy rates among young women, and poorer economic outcomes in early adulthood. These results suggest that crime and gang crime activity should be a priority for policymakers who are trying to improve local conditions for the benefit of residents and children.

References

Chetty, R, and N Hendren (2018), “The effects of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: Childhood exposure effects”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(3): 1107–62.

Chetty, R, N Hendren, and L Katz (2016), “The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment”, American Economic Review 106(4): 855–902.

Damm, A P, and C Dustmann (2014), “Does growing up in a high crime neighborhood affect youth criminal behavior?”, American Economic Review 104(6): 1806–32.

Deming, D, S Ross, and S Billings (2016), “Neighbourhood spillovers in youth crime: Social interactions matter”, VoxEU.org, 11 July.

Dustmann, C, and R Landersø (2018), “Social multipliers in crime: Measuring the spillover effects of criminal behaviour”, VoxEU.org, 18 May.

Dustmann, C, M Mertz, and A Okatenko (2023), “Neighbourhood gangs, crime spillovers, and teenage motherhood”, Economic Journal (forthcoming) and CReAM Discussion Paper 04/23.

Dustmann, C, K Vasiljeva, and A Piil Damm (2019), “Refugee migration and electoral outcomes”, Review of Economic Studies 86(5): 2035–91.

Ingoldsby, E M, and D S Shaw (2002), “Neighborhood contextual factors and early-starting antisocial pathways”, Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 5: 21–55.

Sanders, S G (2011), “Crime and the family: Lessons from teenage childbearing”, in P Cook, J Ludwig and J McCrary (eds.), Controlling Crime: Strategies and Tradeoffs, University of Chicago Press.