Leading artificial intelligence (AI) expert Andrew Ng once characterised AI as “the new electricity” that will transform every sector of the economy (Ng 2017). However, we have had many cycles of hype and ‘winters’ before with AI, which has been around since the 1950s. In recent research, we decided to assess how the new wave of AI is developing and have found evidence that a set of technologies may finally be blossoming, both technically and economically (Bughin et al., 2017).

Our work also turned up additional factoids regarding two other issues heavily debated by economists: the evolution of total productivity growth (Crafts and Mills 2017), and the future of work (Frey and Osborne 2013, Autor 2015, Acemoglu and Restepo 2017). Our emerging messages are that AI is still in its infancy, but it is here to stay. Based on a stratified survey of C-level executives from about 3,000 companies in more than ten major countries, the link between the adoption of AI and expected benefits suggests that AI can bring some material firm-level productivity and profit growth, while employment dynamics may be not as bad as anticipated by some economists, and many luddites. Sure, substitution will happen in favour of smart capital, but the companies adopting AI are also the ones pushing for more employment too, especially those companies which leverage AI as a way to innovate and expand output, in consistency with other stylised facts of technological change and employment (Spiezia and Vivarelli 2000).

A new spring for AI

To put it simply, the Industrial Revolution was about machines enhancing human muscle power. The AI revolution is about machines enhancing human brain power. In our work, we have adopted a functional view of AI, that is, we focus on proven technologies such as computer vision, natural language processing, virtual assistants, smart robotics, and autonomous vehicles, all of which are underpinned by a new generation of machine-learning algorithms.

The accuracy of computer vision, for instance, has been increasing all the time. Five years ago, machines were able to correctly recognise images 70% of the time, while humans succeeded 95% of the time. Better data, improved algorithms, and faster computers have raised machines’ accuracy rate to 96%. And as humans, we remain stuck at 95%. Regarding smart robotics, Amazon has managed to improve performance to a stage where robots can reduce click-and-ship time from one hour to 15 minutes, and in half the space needed when humans have to do the back-office jobs.

There are three reasons why AI is experiencing a new spring and will not go way.

- First, more and more of clever investors, from venture capital and private equity, have tripled their AI investments over the past three years are now investing billions in AI. And even if this is small option bets – about 3% of total venture capital funding today – it is growing very quickly, even faster than biotech.

- Second, while private equity and venture capital firms can still be wrong, of course, we found that corporate investment in AI is already three times the amount of private equity and venture capital firms. Among the corporations betting on AI, the most bullish are high-tech companies such as Intel and Samsung, along with the digital native players, such as Alphabet, Facebook and Amazon. Automotive companies are active, too — think about GM acquiring Cruise Automation for more than $1 billion last year. For anyone questioning the wisdom of paying so much for relatively new companies, it is worth noting that AI investments are already paying off — remember Kiva, the robotics company Amazon bought for $775 million in 2012? Kiva robotics used for logistics in Amazon reported to generate returns on investment of 50% for its new owner.

- Third, the set of AI technologies we focus on are actually being deployed (see Figure 1). In our survey of more than 3,000 businesses, we found two-thirds of the companies are AI-aware. They fall into three clusters. About 20% are already serious adopters – mostly deploying machine learning or computer vision technologies, mirroring the investments made by venture capital, private equity, and high-tech firms. About an extra 40% of firms have begun to experiment or are partial adopters. The others are not yet experimenting or implementing, but still this means that a majority is trying. And more: out of the 40% who are not adopting, the main reason isn’t that they don’t believe in AI. Our research shows there is a mix of commercial and technical obstacles; regarding the later, 28% of firms don’t feel they have the technical capabilities to implement.

Figure 1 The degree of AI awareness by technology

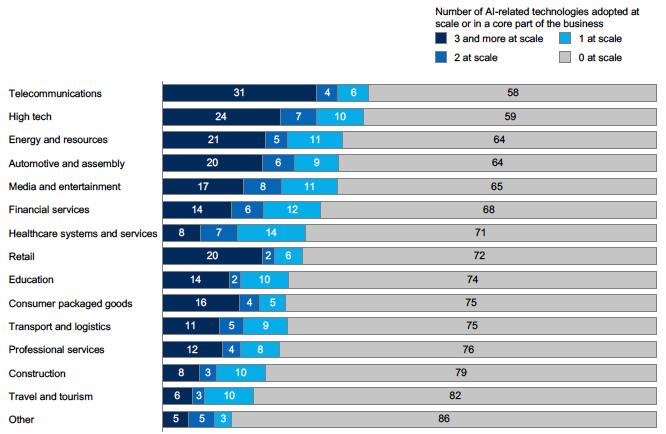

Figure 2 State of AI adoption by sector

The likely economics of AI diffusion

If AI is making inroads into firms, the next question is how this will diffuse, and under what economic equation. We used a simple model in which the profit-development expectations of an industry/firm are related to the extent of its adopting AI at scale. As AI adoption is likely to depend on industry/firm health, we proceeded in two-step estimations: first, we made a logistic model of adoption; then we used the fitted adoption as a regressor in the profit equation. We are obviously aware of the limitation of our data, so our analyses must be taken with caution, but they are the first large-scale evidence of AI on supply economics.

AI diffusion drivers

We first aggregated the data by 15 industries, and then went on to dig deeper by company. Regarding the industry lens, the sectors leading on AI are high-tech, telecoms, and automotive, followed by media and finance (Figure 2). Those sectors are both the most digitised, and the ones predicting high future demand for AI-based business models, and products and services. In fact, it appears that AI is not something companies can easily leapfrog to. Companies need to have started the digital journey to be ready to adopt AI; in fact, the cross-industry correlation between our digital index (a measure of digital assets and usage developed in Digital Europe by MGI) and the same measure adapted to build the AI index (a measure of AI investments and usage) is up to 0.55, and strongly significant. Further, the sectors with a high propensity to adopt AI are also the sectors with the largest spread in profit margin and revenue growth, reflecting sectors facing larger disruption.

We went on to develop correlates of company adoption of AI technology by sector, a step made possible because we have collected roughly 200 companies for 15 industries. Acknowledging all the caveats of survey answers and the longitudinal nature of our panel, we nevertheless found five strong correlates on the probability to adopt AI at scale for each of the five AI-based technologies, across the 15 industries we studied. The analysis at the firm level confirms the industry lens of a link between digital maturity and AI adoption, and between profit expectations and pace of AI adoption. Using the odd ratio to rank the factors, from the smallest to highest effect, we discovered the following stylised facts:

- Adoption is more visible among larger companies — in particular, the effect is the most pronounced within the tech giants, who are already taking major options in AI (see above).

- In almost every industry, AI-adopting companies have significant support from the C-suite; the CEO and other leaders of the business understand and support the adoption of AI technology.

- Adoption is systematically more frequent for companies that already have invested in tech infrastructure that is amenable to AI, which means companies that have invested in big data and cloud-based architecture.

- Companies are more inclined to adopt AI right at the core of their businesses, close to the areas where they are creating the most value.

- Companies that invest in AI have already anticipated a strong business case that relies as much on growing revenues as on cutting costs.

Linking performance and AI diffusion

We used variables described in points 2 through 4 as valid instrumental variables (IV) correlated with AI adoption, to estimate the effect of AI adoption on profit margin development of companies (we omitted the variable “size” as well as the variable “expected benefits” for IV because both could be correlated directly to profit margin development; typical validity tests confirm our list of IV variables cannot be rejected). The equation was estimated industry by industry, with a set of firm control (headquarters location and level of existing profit margin, among others). We found that the IV effect of AI adoption was statistically positive for 12 out of the 15 sectors, even if the variance explained remains limited (on average, between 8-15% of profit development variance among firms of the same industry). This effect, however, ties well with the fact that in our sample, more than 70% of AI adopters anticipate that AI will bring significant competitive advantage in their industry (versus 45% for non-adopters).

AI and our economic future

In passing, the above can be leveraged to discuss two important issues that economists put forward nowadays. The first is whether AI can be part of the solution to restore the apparently vanishing total factor productivity growth in our developed economies. The second is whether employment will be fully depleted if AI fully substitutes smart AI-based capital for labour. This was not the core of our research, but we have a few side findings to help fuel the current debate.

AI and productivity

Using an output view of profit function, it is well known that growth in technical change, or total productivity growth, is a function of profit deployment as well as the of expansion of output in the long-term (in the short term, we should add a capacity utilisation term; see Karagiannis and Mergos 2000). The expansion of output is positive (negative) if there are increasing (decreasing) returns to scale. We can compute the profit deployment linked to AI from our estimate above, which in our case averages between 5% and 12% depending on the industry. Hence, total relative productivity change between adopting and non-adopting firms could be large, and could be even higher if one believes that economies of scale can emerge out of AI. The range of firm productivity uplift is comparable to that found elsewhere, such as for digital technology in general (Brynjolfsson et al. 2011) or for big data (Tambe 2014, Bughin 2016).

AI and employment

The mainstream narrative among labour economists is that AI-based automation is likely to make many tasks (and, by aggregation, many current occupations) obsolete. The scope and speed at which this might happen may imply major technological unemployment.

Obviously, the full macroeconomic effect will depend on whether new jobs will be created in adopting industries both as a result of new types of occupations or as a way to support expansion in output, and whether productivity gains captured from AI will create large overspills in the rest of the structure of economy (e.g. Gregory et al. 2016). Our simple maths of the productivity gain impact above imply that it could be as large as those from earlier rollouts of digital technologies.

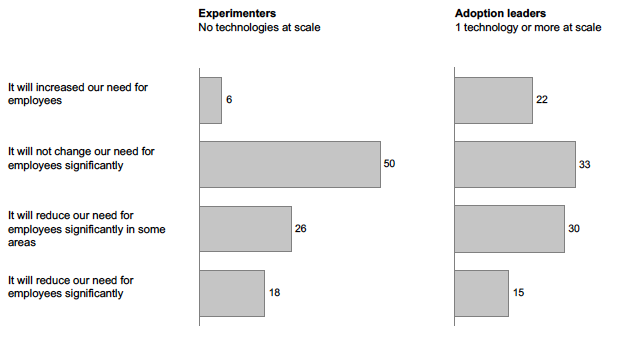

Regarding the effects on own-firm employment, our survey asked about the effects on employment as a result of AI adoption (Figure 3). For more detail, we also highlight companies that identified themselves as only experimenting with AI and not yet adopting at scale; in general, the portion of companies expecting a reduction is rather similar, about 45% for both adopters and experimenters; but those who have already adopted AI show significantly more willingness to increase employment (22% versus 6%). If the portion of increase is only half the portion of firms that anticipate a decrease, this ratio is surprisingly close to the ones observed for new technology introductions across the decades as shown in Atkinson (2013). Zooming in further on companies willing to increase employment, we were also able to see that those companies use AI more to expand output and refine products and services, as anticipated by Spiezia and Vivarelli (2000).

Thus, we conclude that AI is here to stay, and that the adoption of AI by firms is driven by sufficient economic forces. Those forces will further accelerate the substitution of (old) human tasks, but we conjecture from our data that the gain in productivity, together with the innovation that AI can bring into the marketplace, may well be more welcoming than self-defeating, even for future employment (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2017).

Figure 3 Expected change in employment due to AI adoption

References

Acemoglu, D, and P Restrepo (2017), “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets”, NBER Working Paper No. 23285.

Arntz, M, T Gregory and U Zierahn (2016), “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD countries: A Comparative Analysis”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No. 189.

Atkinson, R (2013), “Stop saying that robots are destroying jobs — they are not”, Technology Review, September.

Autor, D (2015), “Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29 (3): 3–30.

Brynjolfsson E, L Hitt and H Kim, (2011) “Strength in Numbers: How does data-driven decision-making affect firm performance?”, MIT Sloan School of Management, December.

Bughin, J, E Hazan, S Ramaswamy, M Chui, T Allas, P Dahlström, N Henke and M Trench (2017), Artificial Intelligence: the next digital frontier, McKinsey Global Institute.

Bughin, J (2016), “Reaping the benefits of big data in telecom”, Journal of Big Data 3(1): 14.

Bughin, J and N van Zeebroeck (2017), “The best response to digital disruption,” Sloan Management Review, Summer.

Crafts, N, and T C Mills (2017), “Trend TFP Growth in the United States: Forecasts versus Outcomes”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12029.

Frey, C, and M Osborne (2013), “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?” Oxford Martin School Working Paper, September.

Gregory, T, A Salomons and U Zierahn (2016), “Racing with or against the machine, Evidence from Europe”, ZEW Discussion Paper 16-053.

Karagiannis, G and Mergos, GJ (2000), “Total factor productivity growth and technical change in a profit function framework”, Journal of Productivity Analysis, 14(1), 31–51.

Ng, A (2017), “Artificial Intelligence is the New Electricity”, presentation at the Stanford MSx Future Forum.

Spiezia, V and M Vivarelli (2000), “The Analysis of Technological Change and Employment”, in M Pianta and M Vivarelli (eds), The Employment Impact of Innovation: Evidence and Policy, Routledge, pp. 12–25.

Tambe, P (2014), “Big data investment, skills, and firm value”, Management Science 60(6): 1452–69.