In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, massive unconventional measures employed by the Federal Reserve triggered debates about the consequences of flooding the world with liquidity. A significant adverse consequence of this unprecedented monetary expansion was the Taper Tantrum in 2013 when the Fed expressed a plan to gradually taper its balance sheet in the future, which was followed by turmoil in emerging markets (EMs). Similar concerns have arisen again following the outbreak of the COVID pandemic when the Fed restored many unconventional policies (Kalemli-Ozcan, 2019, 2020), and will surely continue to be on the minds of investors and EM central banks as the Fed begins a new round of tightening.

Decomposing observed US policy surprises into pure monetary policy and information news shocks

In a recent paper (Ciminelli et al. 2021), we revisit the role of US monetary policy in influencing investors’ allocations into and out of international mutual funds – a key driver of cross-border capital flows. We do so having applied a novel variant of the monetary policy shock identification procedure of Bu et al. (2021). The procedure allows us to decompose observed US monetary policy surprises into pure monetary policy shock and information news shock components. The pure monetary policy shock captures a sudden shift in monetary policy that is orthogonal to changes in the economic outlook. The information shock instead captures a change in the policy indicator that depends on changes in the Federal Open Market Committee's economic outlook (even if unexpected by the public). The importance of Fed private information was emphasised by Romer and Romer (2000) and further analysed by Nakamura and Steinsson (2018), among many others. Our paper is the first to make use of this decomposition to analyse capital flows.

Pure monetary policy tightening shocks have conventional, negative effects on international mutual fund investment...

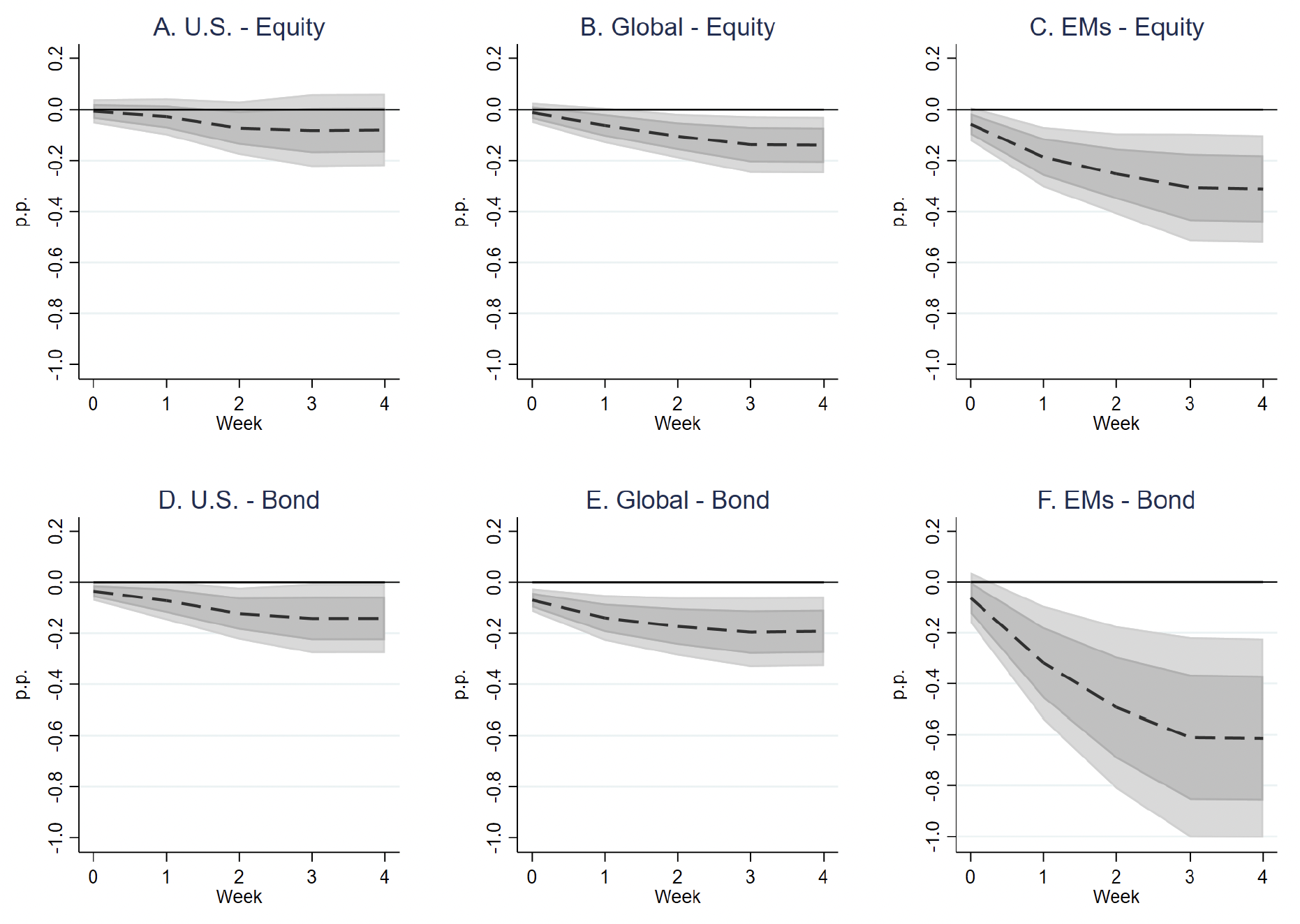

We find a pure US monetary policy shock to have conventional, negative effects on international mutual fund investment. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the effect of a 10-basis-point Fed pure monetary policy shock on investors’ allocations into US, global, and EM mutual funds (measured in percentage points of assets). A tightening shock has negative and persistent effects on allocations into all these types of funds. These effects are largest and more precisely estimated for EM funds. Four weeks after a 10-basis-point shock, flows to EM equity and bond funds are estimated to be about 0.3 and 0.6 percentage points lower, respectively. The same shock has smaller but still statistically significant negative effects on flows to global equity and global bond funds. The response of flows to US funds is similar but less precisely estimated. Overall, these results confirm earlier findings that EM flows are particularly sensitive to US monetary policy (Chari et al. 2020).

Figure 1 Investors’ allocations into mutual funds after a 10-basis-point pure monetary policy shock

Notes: The figure reports the effect of a 10-basis-point positive pure monetary policy shock on allocations into mutual funds over a five-week window, including the week of the shock and the four following one. Dashed black lines report point estimates. Deep and shallow grey areas are 90% and 68% confidence bands. X-axes denote the response horizon (in weeks), with 0 being the week of the shock. Y-axes denote the magnitude of the response (in percentage points of fund assets).

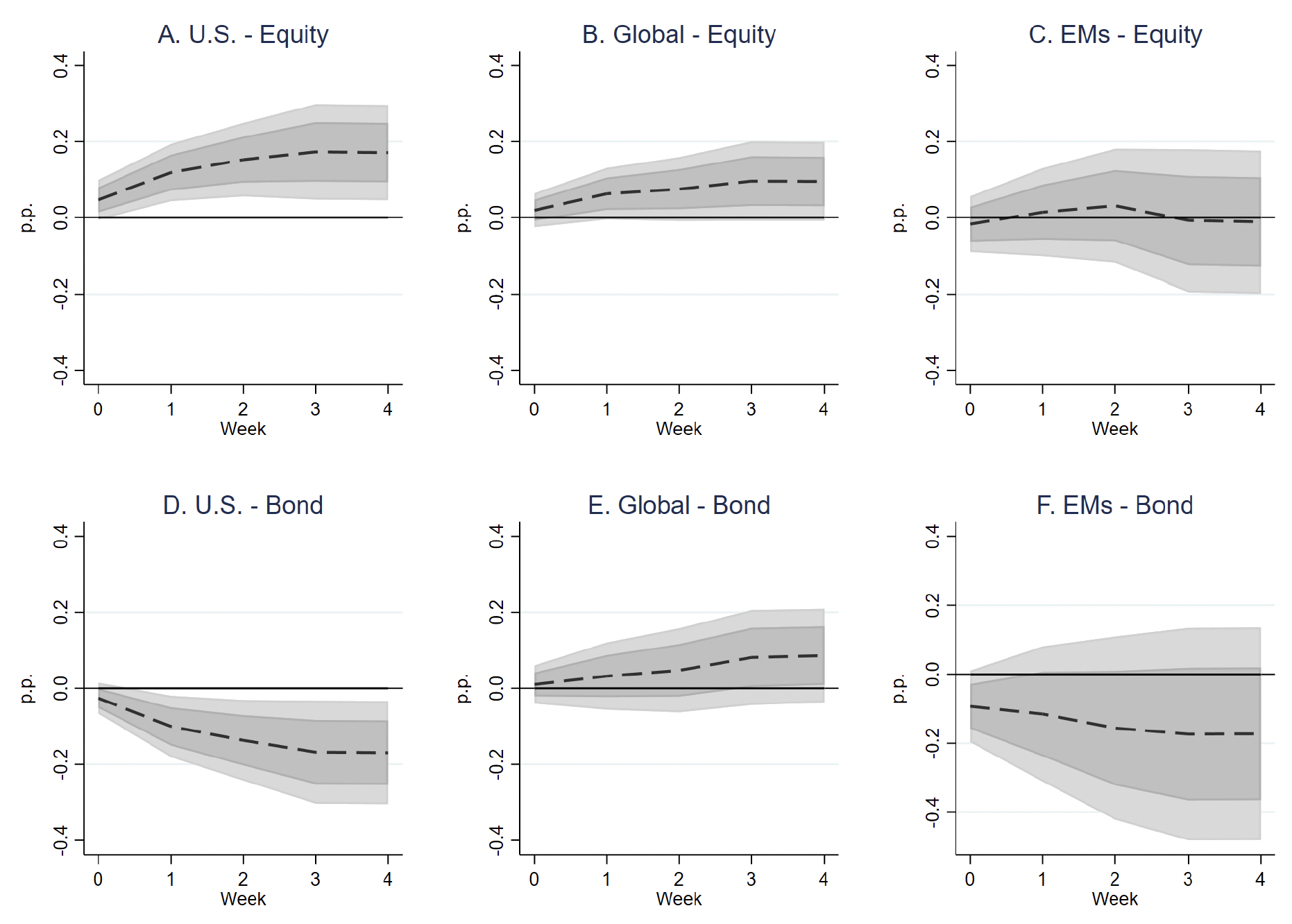

... but positive information shocks do not cause outflows from EM funds and even cause positive allocations into US and global equity funds

On the other hand, information shocks have distinctly different effects. As displayed in Figure 2, a positive shock, indicating higher interest rates against the backdrop of a better economic outlook, (1) does not cause outflows from EM funds, and (2) leads investors to reallocate capital out of safe US bond funds and into growth-sensitive US and global equity funds.

Figure 2 Investors’ allocations into mutual funds after a 10-basis-point information news shock

Notes: The figure reports the effect of a 10-basis-point positive information news shock on allocations into mutual funds over a five-week window, including the week of the shock and the four following one. Dashed black lines report point estimates. Deep and shallow grey areas are 90% and 68% confidence bands. X-axes denote the response horizon (in weeks), with 0 being the week of the shock. Y-axes denote the magnitude of the response (in percentage points of fund assets).

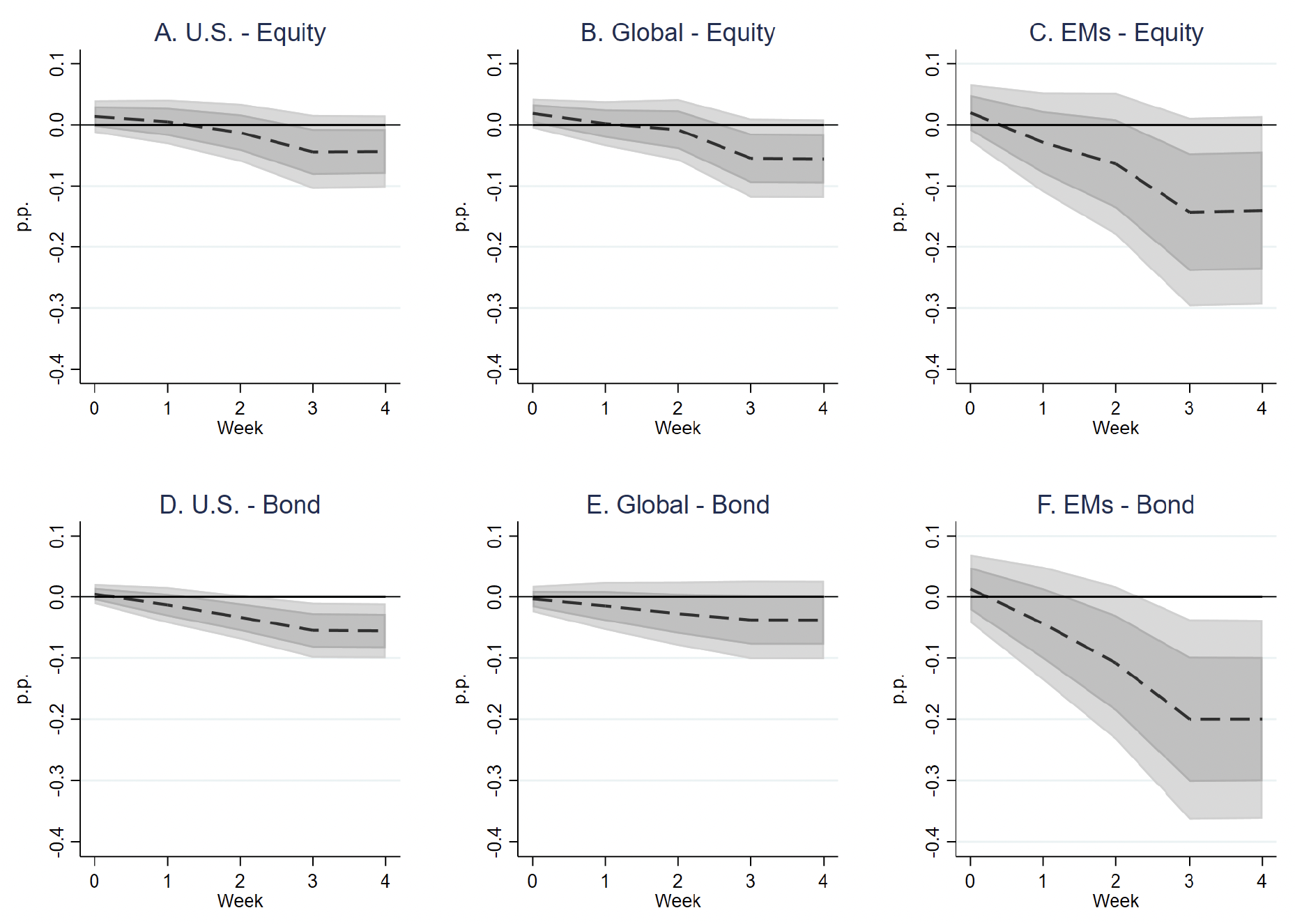

These contrasting results suggest the possibility that analysis of monetary policy shocks without separating the information component may lead to downplaying the importance of Fed monetary policy for international mutual fund investment. To check this, we follow Nakamura and Steinsson and use a composite measure of monetary policy news obtained as the first principal component of the unanticipated change over the 30-minute window around Federal Open Market Committee monetary policy decisions. We then re-estimate the effects of US monetary policy using this combined measure, which does not distinguish between monetary policy shocks and information effects. Because these new estimates mix the (often opposite) effects of pure monetary policy and information shocks, they lead to generally flatter responses, as seen in Figure 3, and the incorrect inference that Fed monetary policy shocks have a relatively small influence.

Figure 3 Investors’ allocations into mutual funds after a 10-basis-point monetary policy ‘news’ shock (without separating pure monetary policy and information news shocks)

Notes: The figure reports the effect of a 10-basis-point monetary policy news shock on allocations into mutual funds over a 5-week window, including the week of the shock and the four following one. Dashed black lines report point estimates. Deep and shallow grey areas are 90% and 68% confidence bands. X-axes denote the response horizon (in weeks), with 0 being the week of the shock. Y-axes denote the magnitude of the response (in percentage points of fund assets).

How can we explain these results?

Our results indicate that an exogenous tightening of US interest rates (pure monetary policy shock) is bad news for EMs, but one that is driven by an upward revision of the economic outlook (information shock) is not. How can we explain these results? The literature postulates the existence of three main transmission channels of US monetary policy for international capital flows: the portfolio-rebalancing channel, the risk-taking channel, and the exchange rate channel (Bruno and Shin 2015, Chari et al. 2020). According to the portfolio-rebalancing channel, investors shift their portfolios towards high-yield EM assets when global interest rates are low and hence investing in long-term advanced economies bonds generates meagre returns. The opposite holds when the Fed tightens policy and interest rates rise. The risk-taking channel operates through the effect of US monetary policy on risk aversion (Bruno and Shin 2015). A tightening in interest rates that increases uncertainty makes investors more reluctant to take on risky positions, which should lead to capital outflows from EMs and other risky funds. Finally, the exchange rate channel depends on the direct effect of the Fed's policy on the US dollar exchange rate, with an appreciation of the dollar leading to capital outflows from other countries, especially EMs.

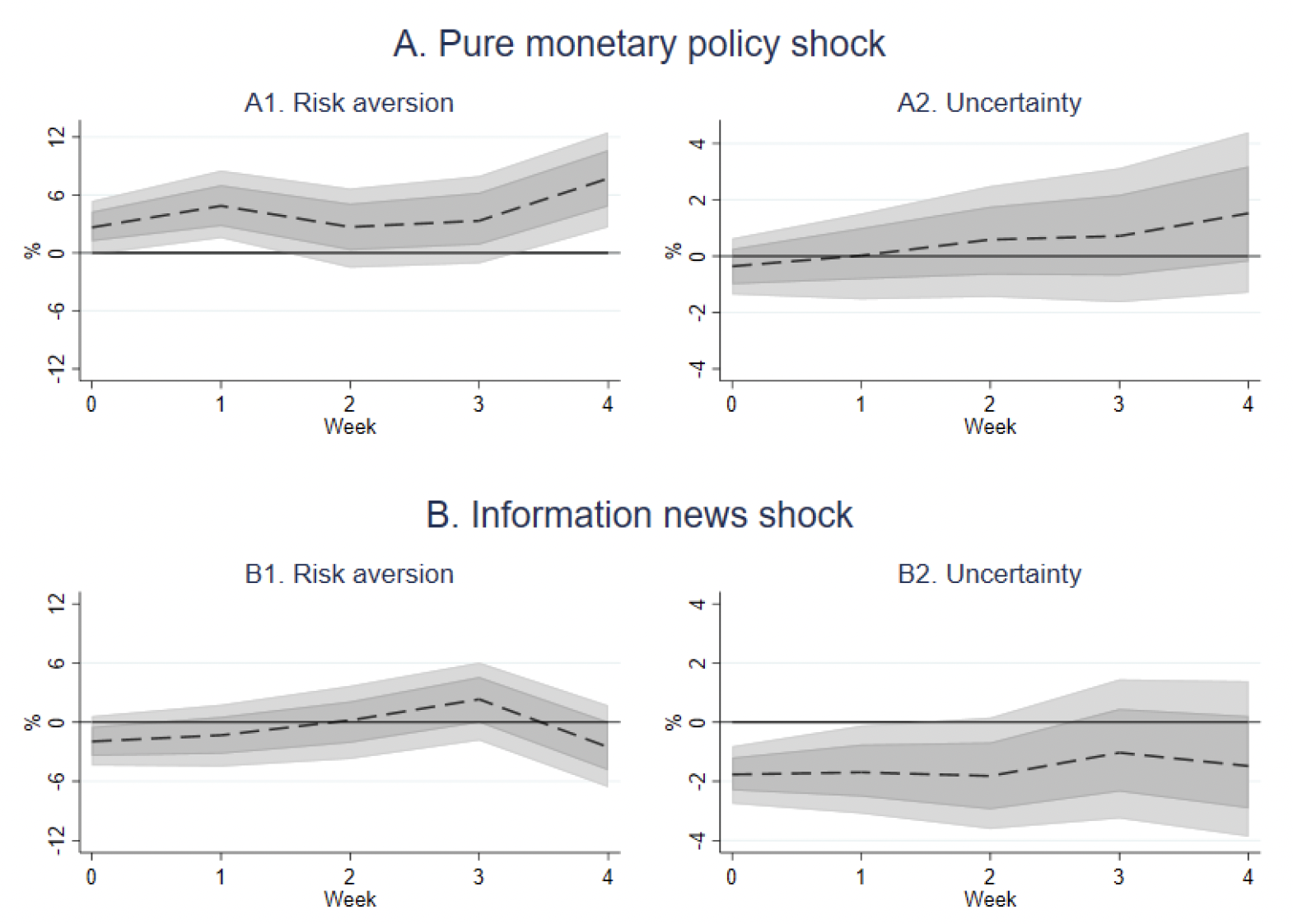

Pure monetary policy shocks heighten risk aversion, while positive information shocks decrease uncertainty

We find evidence suggesting an important role for the risk-taking channel. Pure monetary and information shocks both increase nominal and real interest rates, leading us to downplay the portfolio rebalancing channel as the main driver of our results. However, as shown in Figure 4, the effects of these two shocks on risk taking are sharply different. A pure monetary policy tightening shock substantially increases risk aversion, while positive information shocks decrease uncertainty. As we document, and consistent with the portfolio capital flows literature (Ahmed and Zlate 2014), risk aversion has strong negative effects on flows to EM mutual funds, which explains why pure monetary policy tightening shocks have particularly large negative effects. On the other hand, the decrease in uncertainty following positive information shocks, which is consistent with the information effect, neutralises the negative effects of higher interest rates on higher-yielding assets. This explains why investors shed riskier assets following pure monetary policy shocks but not information shocks.

Figure 4 Effects of Fed's shocks on risk aversion and uncertainty

Notes: The figure reports the effect of a 10-basis-point pure monetary policy and information news shock on risk aversion and uncertainty. Dashed black lines report point estimates. Deep and shallow grey areas are 90% and 68% confidence bands. X-axes denote the response horizon (in weeks), with 0 being the week of the shock. Y-axes denote the magnitude of the response (in percentage points of fund assets).

The important role of the risk-taking channel in driving our results is confirmed when we zoom in on the vast universe of US bond funds. We find that investors sell shares of funds investing in US corporate bonds and buy those of funds investing in safe-haven long-term Treasuries after an increase in interest rates driven by a pure monetary policy shock. Instead, when interest rates increase following a positive information news shock, investors sell long-term Treasury funds and increase allocations into high-yield bond funds.

In our paper, we show that the evidence on the exchange rate channel is mixed. The price of the US dollar shoots up (i.e. the dollar appreciates) following pure monetary policy tightening shocks, while it exhibits a qualitatively similar but weaker and more sluggish response after positive information shocks. Hence, the exchange rate channel seems to work in the same direction as the risk-taking channel, but it cannot explain why investors also marginally reduce their positions in US funds after pure monetary policy shocks. This instead can be rationalised with an increase in risk aversion.

Extensions

We also perform some extensions to these core results. We first exploit information on funds' domicile to explore heterogeneities in the response of US and EM investors. The former sharply decrease exposure to EM assets following a pure monetary policy tightening. This decrease in foreign capital in EMs is partly mitigated by EM investors themselves, who increase flows into EM funds. These results are consistent with home-bias behaviour following heightened risk aversion and more generally suggest that monetary policy tightening shocks in the US cause a decrease in foreign capital. We confirm this intuition in our paper by using country-level data on cross-border flows taking place through investment funds. Fed monetary policy tightening shocks lead to a general decrease in foreign inflows, particularly debt. Although larger in EMs, this decline in foreign capital also affects the US and other developed markets. On the other hand, positive information shocks cause inflows of foreign capital into US equity assets, in line with the news of a stronger economy.

These results beg the natural question of what could be done by EM debt issuers to mitigate the decrease in foreign capital following the Fed’s monetary policy tightening shocks. To investigate, we leverage information on bond funds’ investment mandate. Bond funds differ along several dimensions, including credit quality, currency denomination, and issuer of the bonds in which they can invest. These may affect the response of investors following US shocks. We find that credit quality and currency denomination are important. Other things being equal, outflows from funds investing exclusively in investment grade bonds are about half as a large as outflows from other funds, following a tightening pure monetary policy shock. At the same time, funds which can invest only in hard currency (Swiss franc, euro, pound, US dollar, or yen) bonds suffer much larger outflows than local and mixed currency funds. This result has important policy implications as it suggests that, by issuing debt in local currency, EM issuers may decrease exposure not only to exchange rate fluctuations but also to changes in risk aversion following shocks to US monetary policy.

References

Ahmed, S and A Zlate (2014), "Capital flows to emerging market economies: A brave new world?", Journal of International Money and Finance 48: 221–248.

Bruno, V and H S Shin (2015), “Capital Flows and the Risk-taking Channel of Monetary Policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics 71: 119--132.

Bu, C, J Rogers and W Wu (2021), “A unified measure of Fed monetary policy shocks”, Journal of Monetary Economics 118: 331--349.

Chari, A, K D Stedman and C Lundblad (2020), “Taper tantrums: Quantitative easing, its aftermath, and emerging market capital flows”, The Review of Financial Studies.

Ciminelli, G, J Rogers and W Wu(2021), “The effects of U.S. monetary policy on international mutual fund investment”, SSRN Working Paper.

Jorda, O (2005), “Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections”, American Economic Review 95: 161-182.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S (2019), “US Monetary Policy and International Risk Spillovers”, Jackson Hole Symposium Proceedings.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S (2020), “US monetary policy, international risk spillovers, and policy options,” VoxEU.org, 16 January.

Nakamura, E and J Steinsson (2018), "High-frequency identification of monetary non-neutrality: the information effect", The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133: 1283-1330.