Measuring poverty is expensive. It involves running surveys in faraway places, which are slow and have bad coverage. The global standard, the World Bank Poverty Rate (World Bank 2016), covers less than one third of countries in any given year.

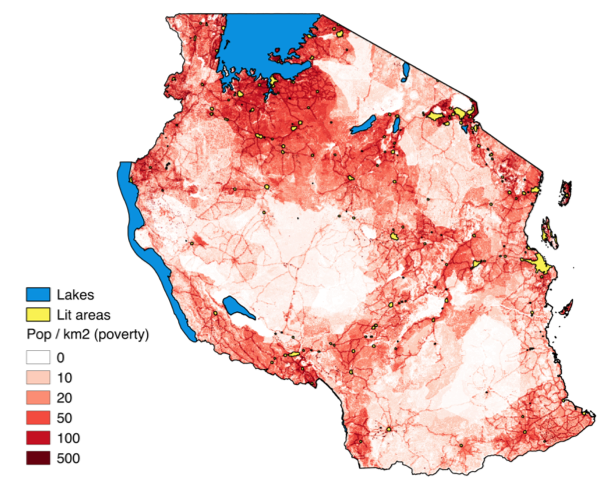

In a recent working paper, we use satellites to measure rural poverty, by counting how many people live in darkness at night (Figure 1) (Smith and Will 2016). This is fast, cheap, accurate and covers the whole world with a 1km2 resolution at regular intervals.

Figure 1 Rural poverty map: Tanzania, 2010

Note: For more examples of rural poverty maps see: https://samuelwills.wordpress.com/poverty-and-darkness/

Source: Image by Thomas McGregor.

Darkness and poverty

We use two types of satellites to count people living in darkness. The first, from the US Defence Meteorological Satellite Program, measures the amount of light emitted at night. The second, called LandScan, estimates population using images of roads, buildings and land cover. The satellites cover every square kilometre of the planet's surface, 100 million data points every year.

Being poor means not being able to meet basic needs like food, shelter, and sanitation. Lighting is only a small part of this. Switching on the lights has a large payoff, however, because it lets people work and study after the sun goes down. People tend to improve their lighting from kerosene to electricity soon after they leave extreme poverty. At this point illumination jumps dramatically and starts to appear in our database: a standard kerosene lamp only delivers 1-6 lux at useful distances, while a 60W electric bulb delivers 100 lux (the western standard for reading is 300 lux).

Light has previously been shown to be a useful, objective way to measure GDP. It has been used to cast doubt on developing countries’ self-reported GDP (Henderson et al. 2012), track the proceeds of piracy into Somalia’s hinterland (Shortland 2011), and expose the favouritism that dictators give to their home towns (Hodler and Raschky 2014).

Looking for poverty under lights is like looking for lost keys under a street lamp. It is better to focus on the darkness. Our paper is the first to focus on the 30% of people outside the OECD, or 50% of people in Africa, who live in darkness at night.

Studying people in darkness is a fast, cheap and accurate way to measure poverty. We compared our measure more than 600,000 DHS household surveys and find that darkness accurately identifies up to 83% of people as above or below the poverty line. For example in the Democratic Republic of Congo the share of poor living in unlit areas at night is 97%, compared to 33% in lit areas; in Bolivia 82% of people in unlit areas are poor, compared to 15% in lit areas.

Tracing the proceeds of oil booms

Darkness lets us study whether oil booms reduce poverty and inequality.

Total lights in oil-rich countries tend to increase during oil booms. In the period 2002-2013, when the price of Brent crude rose from $20 to over $110 per barrel, illumination and GDP per capita in oil-rich countries grew by nearly one third relative to countries without oil. On average, countries that make a giant oil discovery with a net present value worth 100% of GDP see total lighting increase by almost one fifth, and GDP by 8% after ten years, compared to countries that don’t make discoveries.

These booms do not benefit the rural poor. All the extra light during the 2000s oil price boom came from cities and towns, in which illumination grew by 15% and 38%, respectively. The share of people living in darkness stayed the same. New lights did not turn on, and the poor did not move for better opportunities elsewhere. Giant oil discoveries show the same effect. In these cases lighting in towns and cities grew by 15% and 22% respectively after 10 years, but did not cause any lights to be switched on in rural areas. There is some evidence, though, that oil discoveries prompted around 1% of the rural poor to move to towns.

If oil doesn’t turn on the lights, what does?

Evidence suggests that rural areas are steadily becoming illuminated around the world but, if oil booms don’t hasten the process, what causes this to happen?

Looking around the world we find that the probability of an unlit cell becoming lit is increased when it is adjacent to existing lit cells, close to the capital, has a high population density, or is in a country with high aggregate light growth since the start of the sample. We do not find that the first three mechanisms are more active in oil-dependent countries during a price boom. If anything, oil-rich countries are less efficient at converting growth into lower poverty than other countries.

This work provides, for the first time, global evidence that oil systematically increases inequality in the countries that discover it. Using darkness to measure poverty also opens up possibilities for allocating aid and testing policies designed to improve the lives of the world’s poor. The first step in winning the war on poverty is to know where the enemy is.

References

Henderson, J. V., Storeygard A. and Weil D. N. (2012), “Measuring economic growth from outer space”, The American Economic Review, 994–1028.

Hodler, R. & Raschky, P. (2014), “Regional Favoritism”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(2), 995-1033.

Shortland, A. (2011), "'Robin Hook': The Developmental Effects of Somali Piracy."

Smith, B. and Wills, S. (2016), “Left in the Dark? Oil and Rural Poverty”, OxCarre Working Paper 164, Department of Economics, University of Oxford.

World Bank (2016), Poverty & equity data. http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/home/