The Covid-19 pandemic has imposed significant economic hardships on affected economies. The aggregate effects on national incomes have been significant. Unemployment in the US rose from 3.5% in February 2020, just before the impact of the pandemic, to 14.7% by April 2020. Relative to a year ago, second-quarter GDP in the US dropped by 9.0%; in the euro area, the fall was 14.6%. Worldwide, the modal growth rate of GDP fell more than 10 percentage points in the first half of 2020 relative to the most recent IMF forecast (Furceri et al. 2021).

In response to the deep pandemic recession, national governments and the EU have responded with monetary and fiscal policies meant to stimulate their economies. Recently, President Biden proposed, and Congress approved, a $1.9 trillion debt-financed increase in national spending known as the American Rescue Plan (ARP). The plan includes $320 billion in assistance for state and local governments to offset pandemic-induced losses in state and local government revenue and spending. Clemens and Veuger (2020) estimate the pandemic-induced revenue loss for state and local governments at $236 billion. However, the allocation of this assistance has proven to be a point of significant partisan conflict between the Democratic administration and Republican governors. The administration wants states to stimulate the economy via outlays or transfers while Republican governors want to give tax cuts.1 Our research, first motivated by partisan conflicts in the passage and implementation of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), suggests that the resolution of these disagreements will have significant consequences for the overall impact of the ARP on the aggregate economy (Carlino et al. 2021).

In contrast to a unitary government, governments in economic unions face an added layer of complication when making fiscal policy. In unitary democracies, policies are decided and implemented by a single national party or majority coalition. In economic unions, public services other than national defence are provided by independently elected state or provincial governments (de Mello and Jalles 2020).2 If the national government wants to spend money, much of that spending will require the cooperation of these state governments, and hence, cooperation may not be forthcoming.3 When policy preferences of elected national and state leaders are in conflict, there is an agency problem. The familiar theory of economic federalism ignores this conflict. Our recent research addresses it directly and finds partisan differences can have a significant impact on overall policy effectiveness.

Partisan policy differences arise when parties care about outcomes, not just winning elections (Harrington 1992).4 With partisan politics and strong parties, candidates must first win a party nomination before running in the general election. Winning the party’s nomination pulls candidates away from the state-wide median policy position and towards positions favoured by the separate party medians.

Our research assumes that the important state election is that for the state governor and we test for partisan policy differences using a sample of all governor elections from 1983-2014 (Kousser and Phillips 2012). Only governors who won office in close elections were included in the final estimation, an approach called ‘regression discontinuity design’ (RDD). Governors from close elections are thought to be chosen for office because of random factors such as weather, a bad debate outcome, or perhaps a scandal unrelated to policy choices or performance. Comparing policy choices across ‘randomly’ elected Democratic and Republican governors will reveal partisan based preferences. How do governors allocate intergovernmental aid from the central government, and specifically, do they spend national assistance on state public goods or allocate aid to tax relief? Our answer to this question is that Democrats fully spend the aid, dollar for dollar; Republicans allocate all assistance to tax relief, dollar for dollar.5 Given these partisan differences in the allocation of intergovernmental aid, do they matter for the impact of aid on the macro economy? Our answer is yes, as revealed by both a general equilibrium New Keynesian model and from direct, econometric estimates of US GDP responses to intergovernmental aid.

Our model’s economy has a private and a government sector. The private sector describes household and firm behaviour. Within the government sector, the central bank follows a standard interest rate rule. State governments provide public services consumed by households (e.g. education), public infrastructure used by private firms (e.g. roads and sewers), and transfers to households (or equivalently, local governments). State governments face a balanced budget constraint, use a distortionary tax on labour income, and receive intergovernmental transfers from the national government. Based upon underlying partisan preferences, the state’s elected governor decides the allocation of intergovernmental aid between spending and tax relief. The national government provides national public goods (e.g. national parks or national defence), transfers to households, and intergovernmental transfers to state governments. The national government can borrow and has access to a lump-sum tax and a distortionary tax on labour income. Finally, state economies, all of the same size, are open economies with trade between states. With trade, there can be fiscal spillovers as demand for goods and services in one state increases output in neighbouring states.6

We study the impact of intergovernmental aid on the level of aggregate GDP, allocating aid to state spending (services, infrastructure, and transfers) in Democratic states and to state tax relief in Republican states as predicted by our empirical analysis. For purposes of illustration, half the states are assigned to have Democratic governors and half Republican (today, the Republican percentage of governors is 54%). Our simulations set the level of intergovernmental aid at $320 billion, the amount of federal to state aid in President’s Obama’s 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and also the total proposed in Biden’s American Rescue Plan.

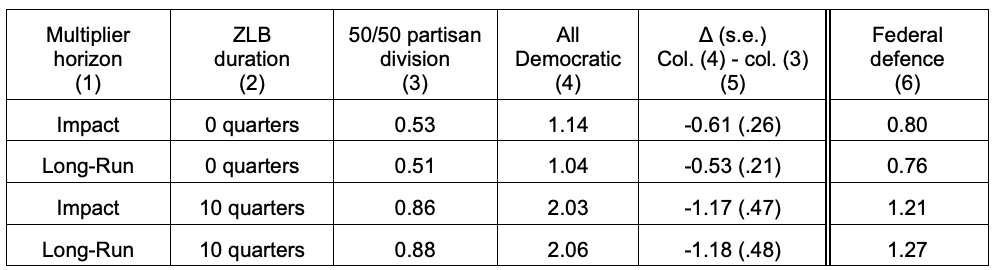

Our results compare the impact and long-run (discounted value) multipliers for federal to state aid in two scenarios: one where all states are run by Democratic governors, and one where half the states are Democratic and half are Republican (Table 1). Impact multipliers estimate the increase in income after one quarter and our long-run multipliers after 20 quarters, discounted to the date of the policy shock. Also shown are the multipliers when we impose the constraint of a zero lower bound (ZLB) on monetary policy. A ZLB limits monetary policy’s offset to expansionary fiscal policy – hence the larger multipliers when the ZLB constraint lasts for 10 quarters. For comparison, we also show fiscal multipliers for direct national defence spending specified to replicate the federal multiplier estimates of Ramey (2011).

Table 1 Impact and long-run multipliers from increased federal aid to states

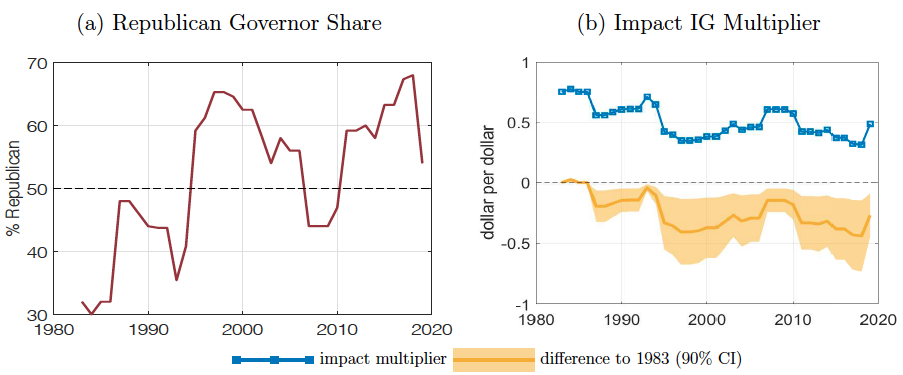

Table 1 offers three conclusions. First, the greater the share of state governors with Democratic spending preferences, the larger the impact and long-run multipliers (columns 3 and 4, Table 1). The result follows from the Keynesian features of our economy favouring government spending. The differences in multipliers are quantitatively and statistically significant (column 5, Table 1). Second, holding nominal interest rates fixed for ten quarters (the ZLB constraint) increases the efficacy of fiscal policy. Third, the ability of fiscal policy to stimulate the aggregate economy depends crucially upon who administers the policy – that is, agency of federal governance. The impact and long-run multipliers for direct federal (defence) spending are shown in column 6 and are bounded by the federal aid multipliers, conditional upon who administers aid policy. The greater the share of governors who are Democratic, the greater the multiplier (Figure 1). As the share of governors who are Republican approaches and exceeds 50%, as is the case today, direct federal spending rather than intergovernmental aid may be the preferred policy for stimulating the aggregate economy.

Figure 1 Share of Republican governors and simulated aid multiplier, 1983-2019

Notes: Panel (a) shows the share of Democratic and Republican governors who are Republican, by year. Panel (b) shows the impact multiplier for intergovernmental transfers in our New Keynesian model of fiscal policy with Republican and Democratic governors, based on estimated partisan differences in their marginal propensity to spend transfer income. The solid dark line traces the value of the simulated aggregate multiplier. The thin line shows the changes in the multiplier relative to zero (no change) and its 90th percentile confidence band, as the share of Republican governors increases above its lowest share of 30% in 1983. As the Republican share rises, the aggregate multiplier declines.

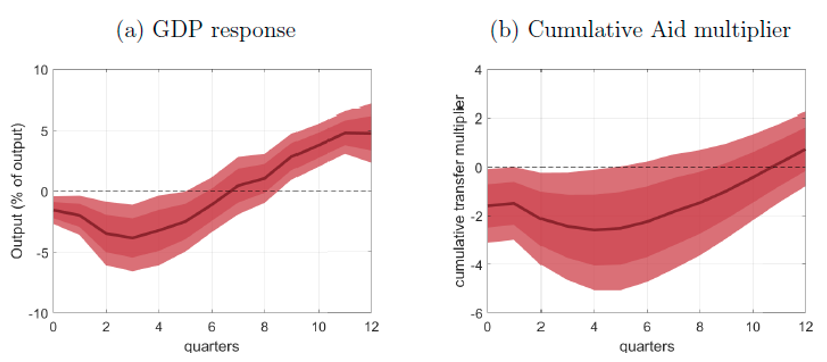

As a final test that agency matters for fiscal policy, we directly estimated the impact of shocks to intergovernmental aid on GDP, conditional on the share of governors who are Republican.7 Figure 1 predicts that a larger share of Republican governors will imply smaller multipliers for aid policy. This is what we find (Figure 2). On impact, and for the first six quarters after the surprise increase in aid, the response of GDP is significantly lower when the share of Republican governors is one standard deviation above average (61% Republican, rather than 50%) (see Figure 2a). After six quarters, GDP is higher with a larger share of Republican governors, reflecting the benefits of Republican tax cuts. Those later gains, however, are not enough to offset the weaker initial performance of the Republican decision to not spend federal aid, as seen in Figure 2b, for the estimated cumulative multiplier.

Figure 2 Change in GDP response and aid multiplier with higher Republican share

Notes: Estimated GDP response and the cumulative multiplier (dark lines) with their 67th and 90th percentile confidence bands for changes in intergovernmental aid when the share of Republican governors is increased by one standard deviation (10.8 percentage points) above the sample (1981-2018) average Republican share.

The ability of citizens to design policies to meet their unique preferences for public goods is a central virtue of federal governance. It is also a vice, however, when the decisions of one state or provincial government impact the economic welfare of its neighbours. In this case, central government policy coordination is required. Coordination may not be possible if the policy preferences of the central government are in conflict with those of state governments responsible for implementing policies. The central government then faces an agency problem. We have documented the importance of such conflicts for the design of US macroeconomic fiscal policies, but the concern is likely to apply more broadly. Similar conflicts in policy preferences may be emerging in the EU, perhaps with similar consequences for the implementation of union-wide policies (Tabellini 2019).

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.

References

Carlino, G, T Drautzburg, R Inman, and N Zarra (2021), “Partisanship and Fiscal Policy in Economic Unions: Evidence from U.S. States”, NBER Working Paper No. 28425.

Clemens, J, and S Veuger (2020), “Fiscal Federalism and the COVID-19 Shock in the US”, VoxEU.org, 28 September.

de Mello, Luiz and João Tovar Jalles (2020), “Intergovernmental Relations: How the Global Crisis Led to Further Decentralization,” VoxEU.org, 08 April.

Furceri, D, M Ganslmeier, J David Ostry, and N Yang (2021), “Initial Output Losses from the Covid-19 Pandemic: Robust Determinants”, IMF Working Paper 21/18.

Harrington, J (1992), “The Role of Party Reputation in the Formation of Policy”, Journal of Public Economics 49: 107-121.

Inman, R (2009), “Flypaper Effect”, in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, S. Durlauf and L. Blume (eds.) Palgrave McMillian, London.

Jordà, Ó (2005), “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections", American Economic Review 95: 161-182.

Kaiser Family Foundation (2019), “Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State".

Kousser, T and J Phillips (2012), The Power of American Governors: Winning on Budget and Losing on Policy, Cambridge University Press, NY.

Nakamura, E and J Steinsson (2014), “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence From U.S. Regions”, American Economic Review 104: 753-792.

Ramey, V (2011), “Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It’s All in the Timing”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1-50.

Tabellini, G (2019), “The Rise of Populism”, VoxEU.org, 29 October.

Endnotes

1 Anticipating Republican resistance, Democrats have included a provision to prevent states from cutting taxes. Republican states have sued to block the provision (see “States Sue Over Restrictions on Stimulus”, New York Times, 18 March 2021).

2 The share of total non-defense government spending done by state and local governments is often as high as 50% and the share grows during periods of economic crises. Intergovernmental aid – such as the American Rescue Plan’s proposed $320 billion – funds much of those increases.

3 For example, President Obama’s Medicaid expansion was limited by the decision of some Republican state governors not to implement the Act’s expanded insurance coverage. See the Washington Post, “Millions Will Remain Uninsured Because of Blocked Medicaid Expansion in States,” November 15, 2013. In contrast, President Trump’s imposition of work requirements for Medicaid recipients has only been implemented by Republican governors; see Kaiser Family Foundation (2019).

4 Only when winning the election is the sole objective of party members will party candidates converge on a common statewide median, revealing no partisan differences.

5 More precisely, we cannot statistically reject the null hypothesis that closely elected Democratic governors spend the full dollar of aid and closely elected Republican governors allocate the full dollar to tax relief. Our exact estimates for incremental spending from one additional dollar of federal aid range from $1.26 (s.e. = .63) to $1.41 (s.e. = .65) for a (closely elected) Democratic governor and - $1.51 (s.e. = 1.03) to -$1.92 (s.e. = .78) less for a (closely elected) Republican governor. It is worth noting that a weighted average of Democratic and Republican governor preferences for allocating federal aid range from .75 to 1.18, consistent with the usual flypaper estimates without controlling for partisanship; see Inman (2009).

6 Our model is based on the framework for open economies first presented in Nakamura and Steinnson (2014).

7 Estimation used the local projection approach of Jordà (2008).