Maintaining public safety is a critical function of national governments, but figuring out the best way to allocate public funds for crime prevention can be a difficult task. In the UK, the debate over policing is currently revolving around two critical issues: the declining effectiveness of the police and the increase in violence in urban areas. At the heart of these concerns, there are reforms due to financial adjustments that have reduced the central government funding for policing by 20% in real terms since 2010, resulting in the closure of 600 out of 900 police stations in England. But is closing police stations a cost-effective solution to budget constraints?

Many studies in criminology and economics have explored the connection between crime and policing. Some have estimated the impact of increases in police manpower on crime (e.g. Di Tella and Schargrosky 2004, Draca et al. 2007, Blanes i Vidal and Mastrobuoni 2017), while others have looked at factors that contribute to police effectiveness, such as management practices (e.g. Ludwig et al. 2022), policing strategies (Weisburd 2021), and technology (e.g. Garicano and Heaton 2006, Rossi and Munyo 2019). Despite this evidence, it remains challenging to evaluate the effects of reductions to the police budget empirically. Previous studies have mostly relied on city-level or police force-level data to analyse the effect of police funding on crime (e.g. Evans and Owens 2007, Machin and Marie 2011). While this approach has yielded valuable insights, a narrow focus on aggregate areas fails to identify the specific mechanisms that connect police resources to crime prevention outcomes. This lack of understanding makes it difficult to formulate policy-relevant conclusions on how to best allocate resources and promote public safety and social welfare (Owens 2020).

The impact of police station closures in London

In my new research (Facchetti 2022), I isolate the causal effect of decreasing spending for policing on crime, police effectiveness, and local welfare by leveraging a reduction in the number of police stations operating in London. Like other police forces, the London police between 2010 and 2016 saw its real-term budget reduced by a quarter as a result of austerity-induced fiscal adjustments initiated by the UK coalition government. The reduction in budget resulted in the closure of 75% of London police stations in less than ten years, doubling the average distance to the nearest station from 1.4 km to 3.1 km.

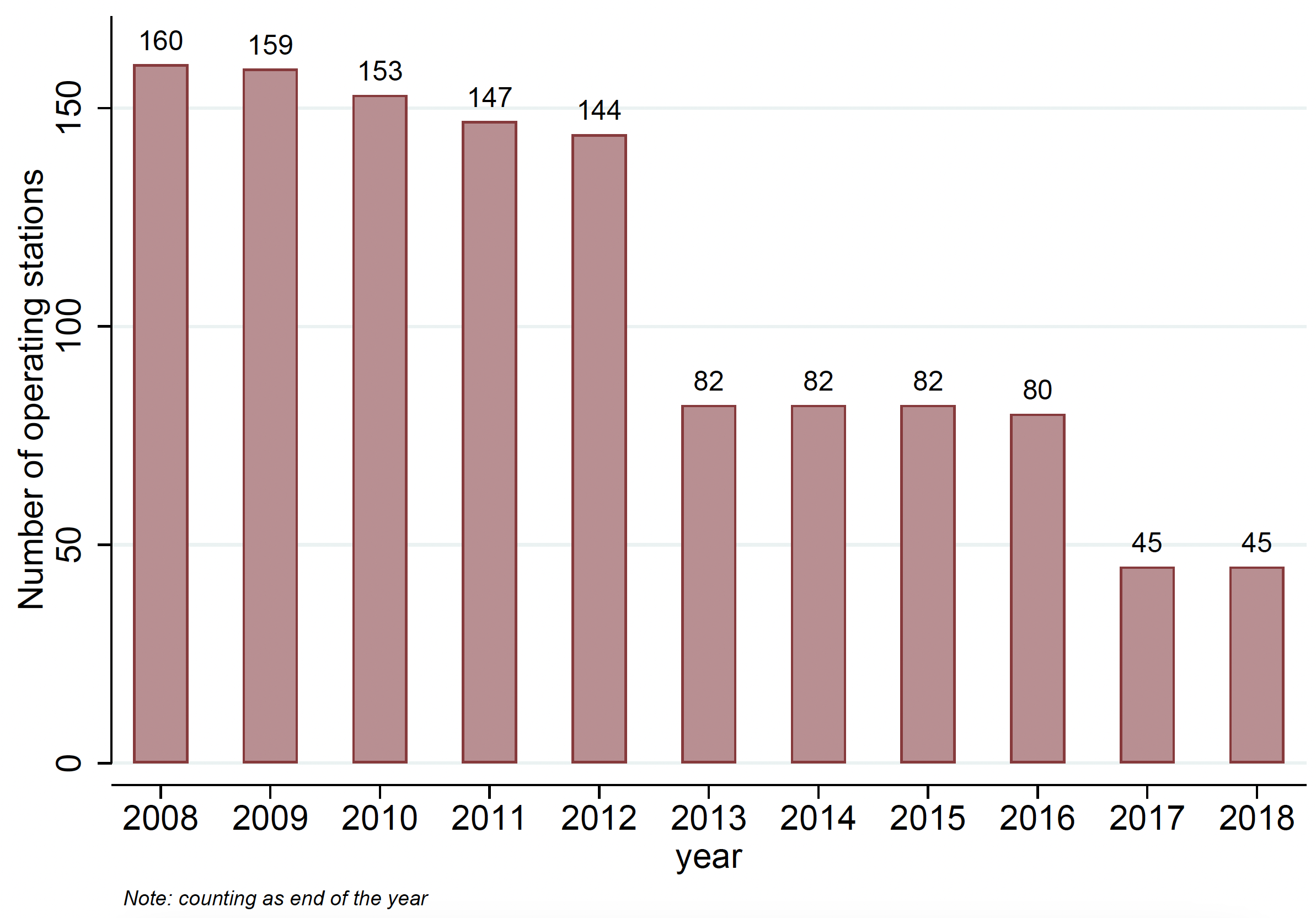

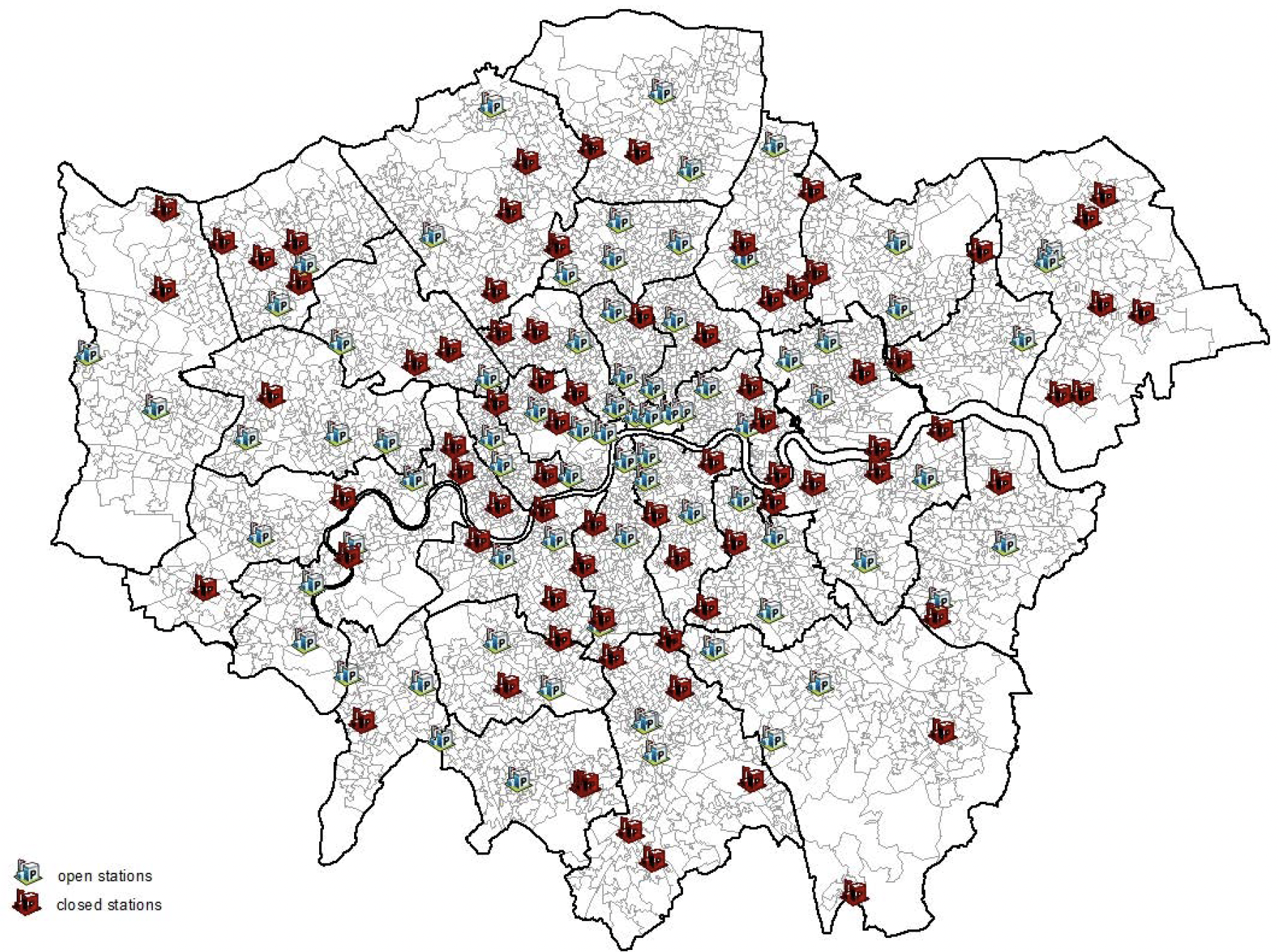

I build a new comprehensive dataset that combines geo-referenced information on crime, police investigations, and police stations. In Figures 1 and 2, I show the number of police stations that were open over time and the locations of all police stations in London, including those that were closed. To estimate the impacts of the closures, I adopt a difference-in-differences approach that exploits the variation over time and space in the closures. I compare the outcomes of small areas whose nearest police station is closed to the outcomes of areas that did not experience any closure. Crucially, the closures did not decrease the number of front-line officers, which allows me to isolate the effect of decreased proximity to the police.

Figure 1 Total number of police stations operating in Greater London between 2008 and 2018

Figure 2 Distribution of open and closed police stations in Greater London

The closure of the police stations resulted in a persistent increase in violent crimes, measured as assaults and murders, of about 11%. The effect is sudden, persists over time, and is concentrated in blocks surrounding closed stations, suggesting that higher distance lowers police deterrence, and therefore increases the incidence of high-severity crimes. Such effect is not driven by crime displaced away from control areas, and it’s not compensated by a larger concentration of police presence close to surviving stations.

Furthermore, the increased distance to the stations, through an associated increase in response time, led to a decline in police ability to solve investigations by 3% with respect to the baseline clearance rate of 18%. Investigating the channels reveals that such decline is attributed to a deterioration in the police's ability to investigate and collect the evidence necessary to clear up crimes, consistent with findings from Blanes i Vidal and Kirchmaier (2018). I do not find support for alternative explanations: this effect is not due to a change in the composition of the police investigations but rather to a decrease in actual police effectiveness.

Finally, I document that austerity-driven budget adjustments have direct implications for citizens’ welfare. First, lower police presence and effectiveness lead to decreased citizens' reporting of low-severity offences. Second, I find that local house prices decrease by 5% per year, suggesting that station closures worsen individuals’ valuations of local areas, burdening local communities with part of the costs of police infrastructure loss. The welfare effects are concentrated in crime hot spots and deprived blocks, further exacerbating the already existing inequalities between poor and rich areas.

Are the closures cost-effective?

A natural question that arises from this work is whether decreased spending in policing is cost-effective with respect to the potential costs in terms of higher violence and lower house prices. I follow the framework proposed by Hendren and Sprung-Keyser (2020) and compute the marginal value of public funds (MVPF), which in this case, computes the value of the money saved, taking into account the negative fiscal externalities on house sales. Decreased spending in policing generates roughly £1.75 in social losses for every saved government pound. This means that increases in crime and decreases in house prices more than offset the public sector savings, even when considering the lower police burden in terms of fewer reported investigations to solve.

Concluding remarks

This research provides valuable insights for policymakers as they navigate the challenges of allocating limited public funding for crime prevention while ensuring community safety and social welfare. Existing research has already shown the adverse political impacts of austerity policies (e.g. Fetzer 2019 in the UK). These findings take this evidence one step further and suggest that blind reductions in police spending can lead to efficiency losses. With a growing need for budgetary restraint, mounting pressure to shift resources away from law enforcement, and decreasing public trust in the police, our findings underscore the importance of understanding which allocation practices are most effective in improving police performance, how to implement such policies, and the effects on the society of doing so.

References

Blanes i Vidal, J and T Kirchmaier (2018), “The effect of police response time on crime clearance rates”, The Review of Economic Studies 85(2): 855–891.

Blanes i Vidal, J and G Mastrobuoni (eds) (2017), “Police Patrols and Crime”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12266.

Di Tella, R and E Schargrodsky (2004), “Do Police Reduce Crime? Estimates Using the Allocation of Police Forces After a Terrorist Attack”, American Economic Review 94(1): 115-13.

Draca, M, S Machin and R Witt (2007), “Policing and crime: evidence from the London bombings re-deployment”, VoxEU.org, 06 August.

Evans, W N and E G Owens (2007), "COPS and Crime", Journal of Public Economics 91(1-2): 181–201.

Facchetti (2022), “Police Infrastructure, Police Performance, and Crime: Evidence from Austerity Cuts”, mimeo.

Fetzer, T (2019), “Austerity caused Brexit”, VoxEU.org, 8 April.

Garicano, L and P Heaton (eds) (2006), “Computing Crime: Information Technology, Police Effectiveness and the Organization of Policing”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 5837.

Hendren, N and B Sprung-Keyser (2020), “A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135: 1209–1318.

Ludwig, J, T Neumann and M Kapustin (2022), “Getting more out of policing in the US”, VoxEU.org, 07 May.

Machin, S and O Marie (2011), “Crime and police resources: The street crime initiative”, Journal of the European Economic Association 9(4): 678–701.

Rossi, M and I Munyo (2019), “Police-monitored cameras and crime”, VoxEU.org, 30 June.

Owens, E (2020), “The economics of policing”, Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics: 1–30.

Weisburd, S (2021), “Police presence, rapid response rates, and crime prevention”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 103(2): 280-293.