Tariffs and subsidies are long-standing trade policy instruments that governments use to conduct international trade policy. It is also well documented that such trade policies are often politically motivated, such that tariffs and subsidies are granted in response to demands by special interest groups for political patronage (e.g. Grossman and Helpman 1994). In addition, trade policies also commonly trigger a chain reaction – a country uses subsidies and/or countervailing duties in response to another country’s trade policies. The recent US-China trade war episode and the 2020 US presidential election provide a unique opportunity to investigate the political economy of trade protection.

The US-China trade war

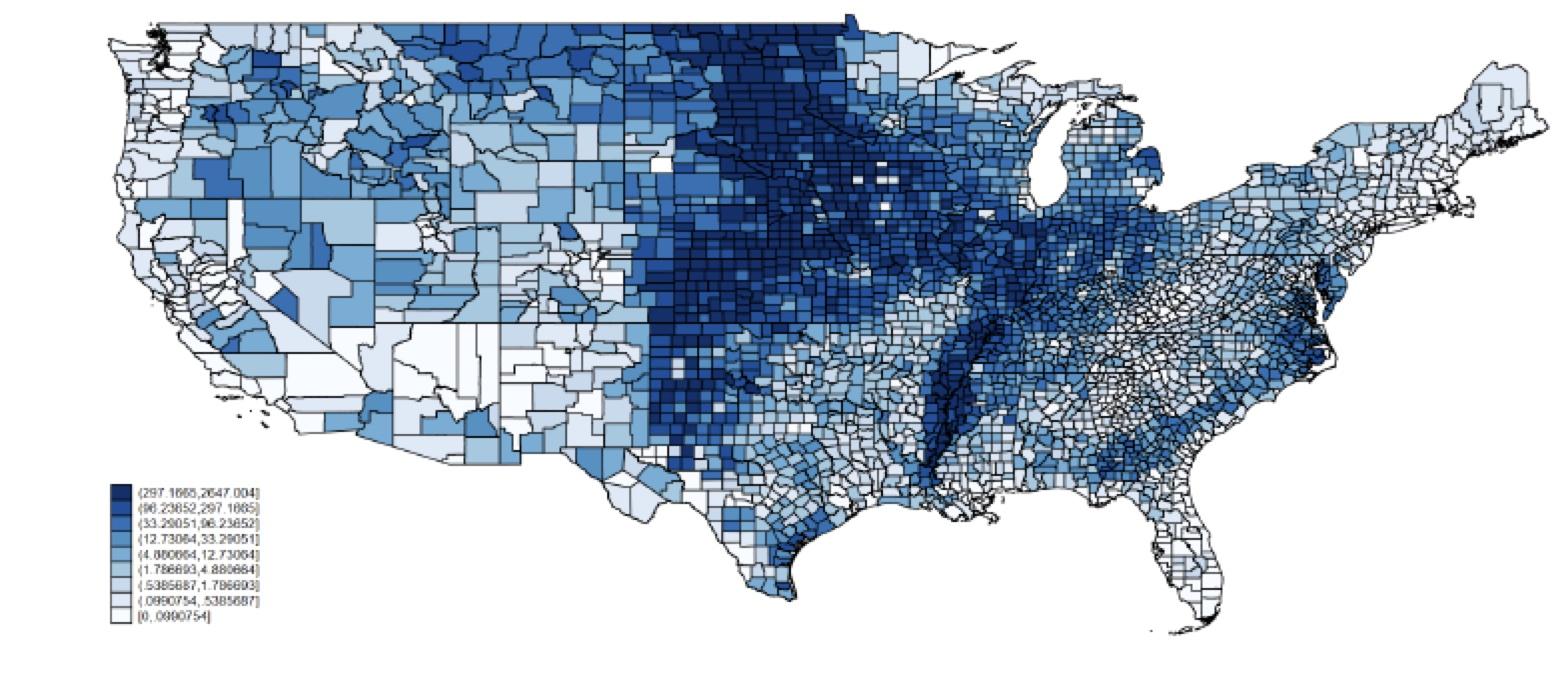

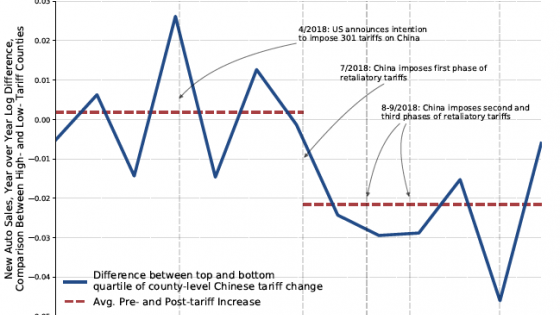

In 2018-2019, the Trump administration imposed a series of tariffs on named trading partners, including China, to reduce the US trade deficit and protect domestic manufacturing jobs. This return to protectionism brought a reaction from China in the form of retaliatory tariffs (Fajgelbaum et al. 2019, Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal 2022), especially on US agricultural products, which affected Republican-leaning agriculture-oriented counties most severely (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 China’s agricultural retaliatory tariff shock per person ($)

Note: Figure 1 shows the county variation in the shock caused by China’s retaliatory tariffs per person. A darker blue indicates a county with a high tariff shock; a lighter blue indicates a county with a lower tariff shock.

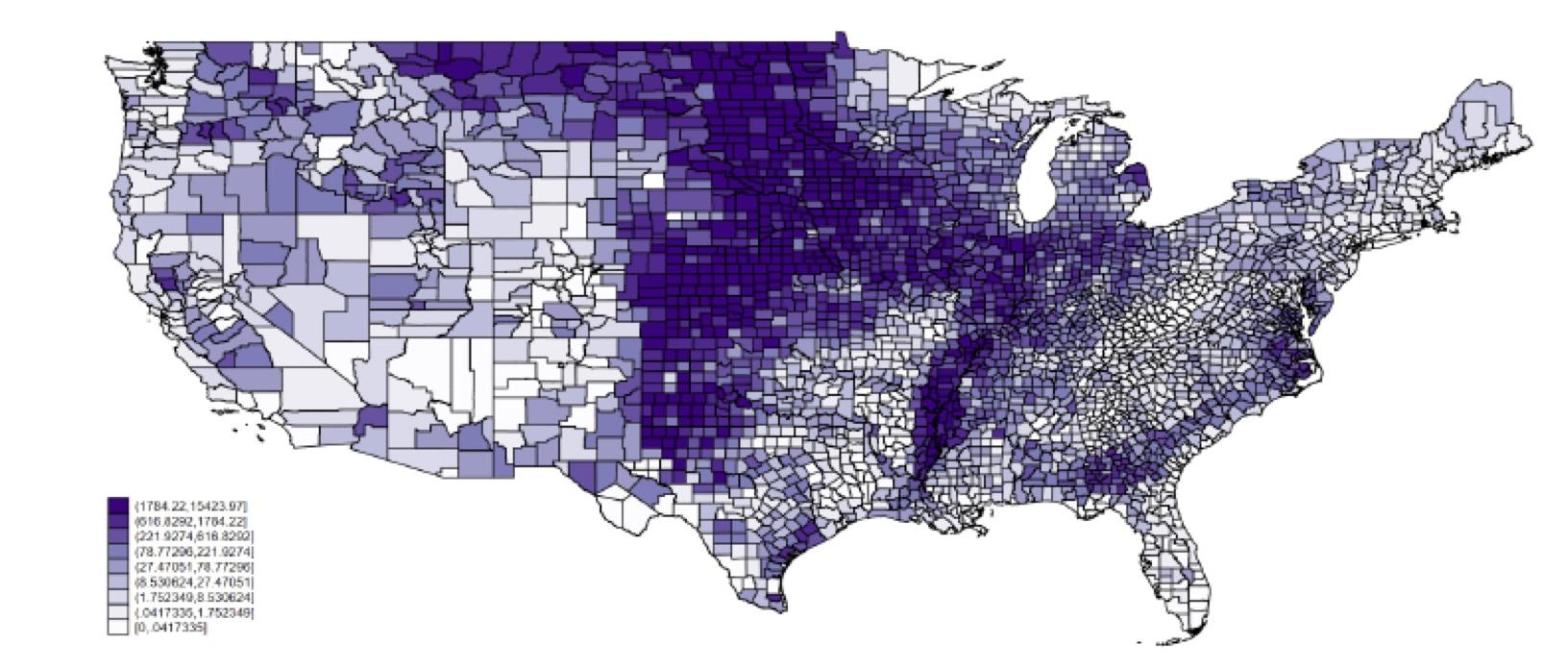

Those retaliatory tariffs appeared to be aimed at the agricultural regions that were a key part of Trump’s political base. In August 2018, the Trump administration went even further and introduced the 2018 Market Facilitation Program (MFP1), which offered direct payments of up to $10 billion to domestic farmers affected by the retaliatory tariffs. As the US-China trade war heated up, the Trump administration made additional direct payments to farmers, as much as $16 billion, through the 2019 Market Facilitation Program (MFP2) in May 2019. Many raised concerns that the MFP1 and MFP2 payments were not fairly distributed across counties and may have been determined by political considerations (GAO 2020) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Market facilitation program subsidies per person ($)

Note: Figure 2 shows the county variation in the MFP payments per person. A darker purple indicates that a county received more MFP payments; a lighter purple indicates that a county received very few MFP payments.

Research questions

We investigate how US voters responded to the US-China trade war and the corresponding US agricultural subsidies in the 2020 US presidential election, as well as whether the distribution of MFP payments was strategically motivated to win the 2020 presidential election (Choi and Lim 2022). The answers to these questions are of great importance. The (mis)allocation of the US agricultural subsidies to the politically connected could impose substantial economic costs on all US taxpayers, who bear the costs of government-provided subsidies. It is equally important to identify the mechanism by which economic shocks, especially trade and agricultural policies, lead to political outcomes, a challenging issue that is poorly understood (Autor et al. 2020).

Political targeting

We begin by assessing whether the US agricultural subsidies in response to the Chinese retaliatory tariffs were distributed unequally across US counties. To do so, we measure the extent to which US counties were hit by the retaliatory Chinese tariffs per person. Specifically, we adopt the measure in Blanchard, Bown, and Chor (2019) and extend their measure in order to answer our research questions in the context of the agricultural sector. We also use the universe of actual county-level disbursements of Market Facilitation Program agricultural subsidy data from the US Department of Agriculture. Using these two measures, we document three stylised facts as follows: (i) Chinese retaliatory tariffs were more directly targeted at Republican-leaning counties; (ii) There was a positive association between the actual disbursements of the MFP and Chinese tariff shocks; (iii) Republican-leaning counties received more MFP payments. The three stylised facts appear to support our conjecture that the distribution of agricultural subsidies was not equal across counties and that political considerations may have been a factor. However, the positive correlations between Chinese retaliatory tariffs, MFP payments, and the Republican vote share do not necessarily mean that the distribution of the MFP payments was politically motivated.

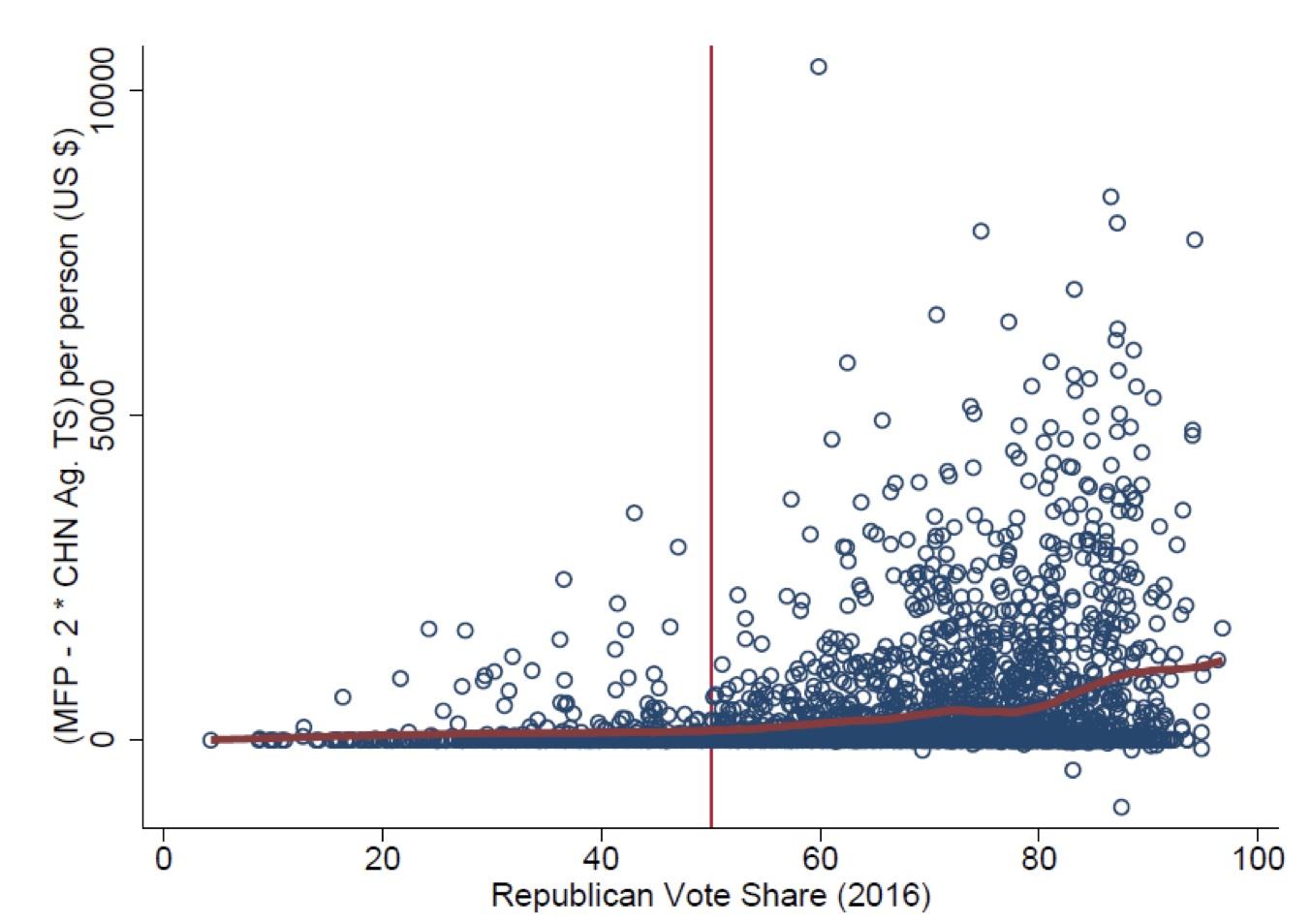

A more meaningful way of evaluating the political considerations that went into the MFP payments would be to calculate a “Net MFP”: the difference between the MFP payment and the damage caused by the retaliatory tariffs at the county level. We find that counties more supportive of the Republican Party saw an increase in their Net MFP; and that the amounts of the Net MFP were notably higher in solidly Republican counties (see Figure 3). These patterns suggest that the swing voter model does not appear to explain the incumbent’s strategy in the 2020 presidential election. However, the larger amounts of the Net MFP in solidly Republican counties appear to support the core voter model. This finding implies that the Trump administration allocated rents in exchange for political patronage.

Figure 3 Net MFP and Republican vote share (2016)

Note: The figure displays a scatter plot between Net MFP (defined as MFP–2×Chinese Agricultural Tariff Shock) and Republican vote share in 2016. The red curve shows a lowess smoother with a bandwidth equal to 0.8.

Did Chinese tariffs and US subsidies affect the 2020 election?

We now analyse how Chinese agricultural trade policy and the US agricultural subsidies altogether – that is, the Net MFP – affected the change in Republican vote share between the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections. We find that the impact of the Net MFP on the Republican share of the two-party (Democratic and Republican) vote is positive. Quantitatively, a one standard deviation increase in exposure to Net MFP is associated with about a 0.38 percentage point increase in the Republican vote share. This result means that the US agricultural subsidies, which were intended to mitigate the Chinese retaliatory tariffs, overcompensated some US voters and led to an increase in the Republican vote share. This is an unintended consequence of China’s retaliatory tariffs, whose original purpose was to undermine Trump’s political base in exchange for lifting trade restrictions that the US had imposed on China. We further investigated whether the two policies affected the counterfactual aggregate election outcome – i.e., how many more Electoral College votes Republicans would have won in the absence of the two policies. We found that the two policies had no impact on the number of states that Republicans carried.

The rural-urban divide in US politics

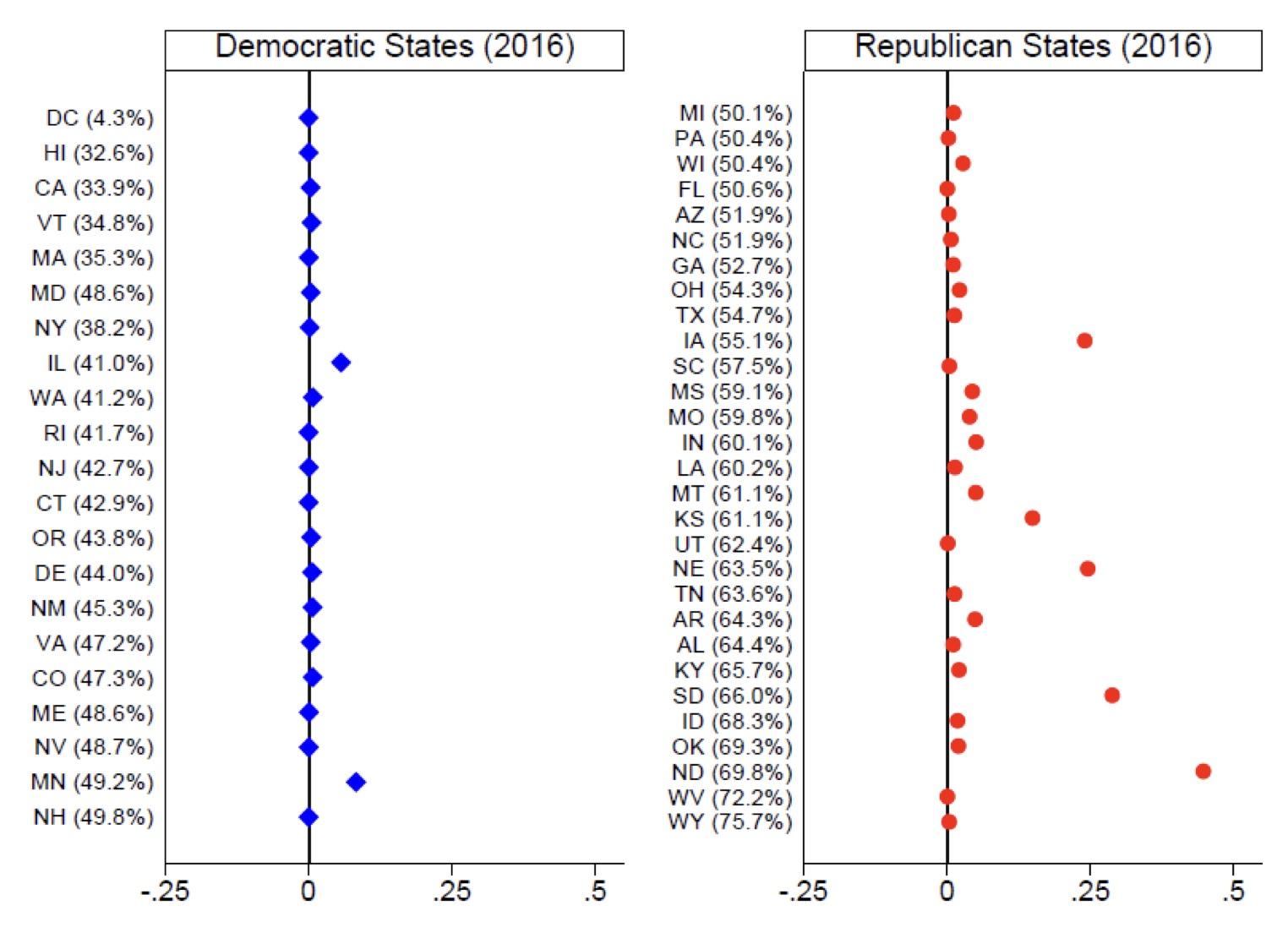

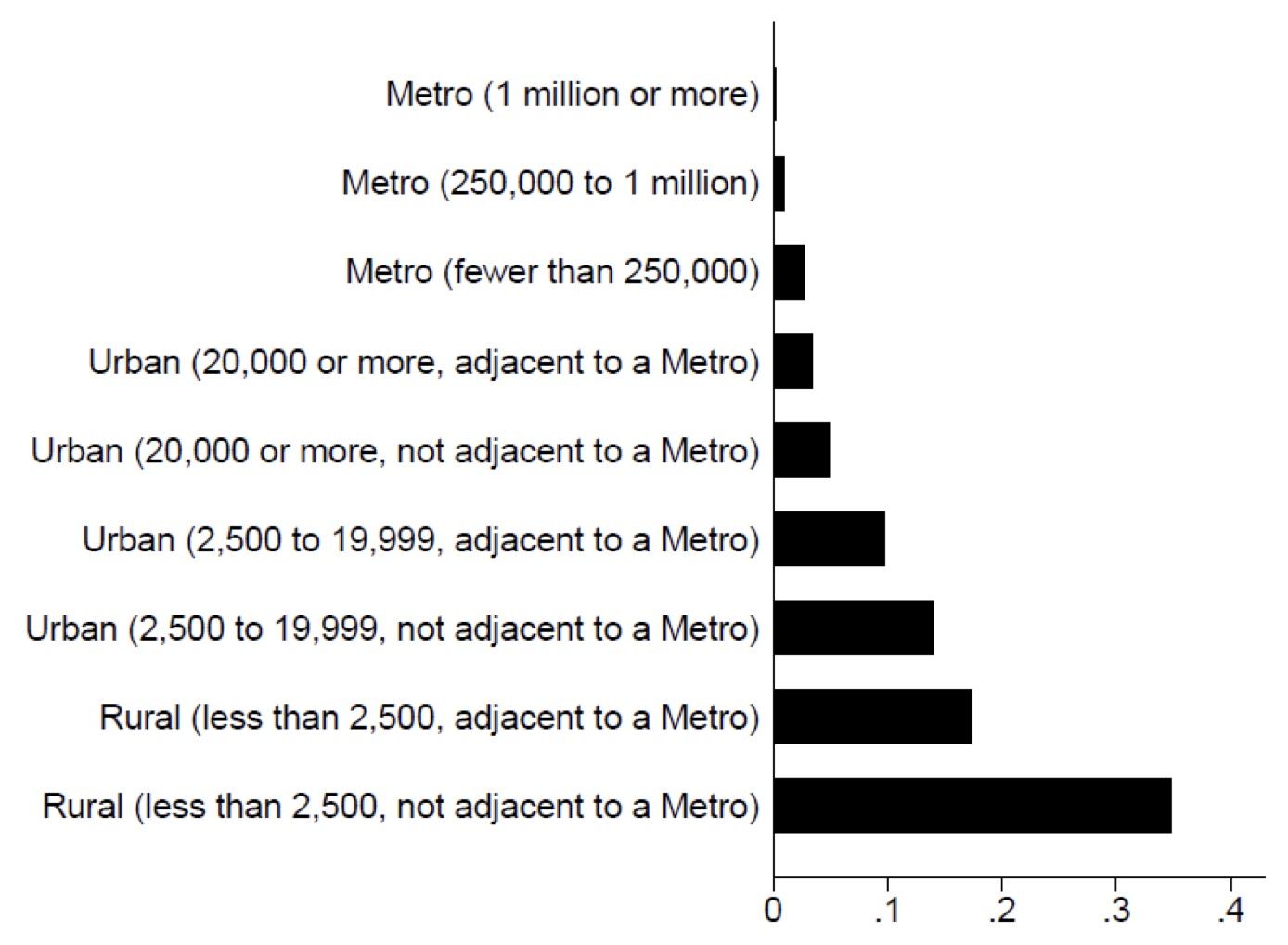

Although our counterfactual analysis shows that China’s retaliatory agricultural tariff and the corresponding US agricultural subsidy likely had no impact on the number of Electoral College votes, we find evidence that the two policies did exacerbate partisan polarisation. The implied election effects of the Net MFP were especially high in solidly Republican states and almost negligible in solidly Democratic states, which contributed to increasing partisan polarisation (see Figure 4). Furthermore, we find evidence of rising rural-urban political polarisation. The implied effect of the Net MFP increases monotonically from the most urban area to the most rural area (see Figure 5).

Figure 4 The implied effect of the Net MFP on political polarization in the 2020 election

Note: "Republican (or Democratic) States (2016)" refers to states where the Republican share of the two-party vote is greater than 0.5 (less than 0.5) in the 2016 presidential election. The number in parentheses is the Republican vote share (%) in the 2016 presidential election for each state. Each dot represents the implied change in the Net MFP on the Republican vote share in 2020.

Figure 5 The implied effect of the Net MFP on rural-urban polarization in the 2020 election

Note: Metro-Urban-Rural counties are defined by the 2013 USDA-ERS Rural-Urban continuum codes. Metropolitan (Metro) counties are defined by the population size of their metro area, and non-metropolitan (urban and rural) counties are defined by the degree of urbanisation and adjacency to metro areas.

Concluding remarks

Exploiting the US-China trade war episode combined with the universe of county-level MFP payments data, we provide unique evidence that the distribution of agricultural subsidies by the incumbent was allocated disproportionately to his supporters for political patronage. This implies that agricultural subsidies, which were used as countermeasures against China’s retaliatory trade policy, can potentially be used as fiscal policy instruments during election periods. Furthermore, our work can shed light on rising political polarisation, especially the rural-urban divide, in the US. Our findings, taken together, deepen our understanding of the political economy of trade protection (Mayer 1984, Grossman and Helpman 1994).

References

Autor, D, D Dorn, G Hanson and K Majlesi (2020), “Importing political polarisation? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure”, American Economic Review 110 (10): 3139-83.

Blanchard, E, C Bown and D Chor (2019), “Trump’s trade war cost Republicans congressional seats in the 2018 midterm elections” , VoxEU.org, 26 Nov.

Choi, J and S Lim (2022), "Tariffs, Agricultural Subsidies, and the 2020 US Presidential Election", American Journal of Agricultural Economics (forthcoming).

Fajgelbaum, P, P Goldberg, P Kennedy and A Khandelwal (2019), “The return to protectionism”, VoxEU.org, 7 Nov.

Fajgelbaum, P and A Khandelwal (2022), "The economic impacts of the US–China trade war", Annual Review of Economics 14: 205-228.

GAO (2020), “USDA Market Facilitation Program: Information on Payments for 2019”, US Government Accountability Office (GAO-20-700R).

Grossman, G and E Helpman (1994), “Protection for Sale”, American Economic Review 84(4): 833-85.

Mayer, W (1984), “Endogenous tariff formation”, American Economic Review 74(5): 970-985.