The use of false or unsubstantiated claims by politicians is hardly a new or unexpected phenomenon. Otto Von Bismark contended that “people never lie so much as after a hunt, during a war or before an election”, and a century later Ronald Reagan ventured that “trees cause more pollution than automobiles do”. Only in the last decade, however, have expressions such as ‘fake news’, ‘alternative facts’, or ‘post-truth politics’ begun making regular appearances in public discourse amid warnings that a proliferation of incorrect or blatantly false public statements may “threaten to warp mass opinion, undermine democratic debate, and distort public policy” (Nyhan 2020).

During the same period, and arguably in response to such phenomena, several independent organisations committed to verifying the factual accuracy of public statements appeared all over the world. Still, whether fact-checking is an effective tool to curb fake news and alternative facts remains an unsettled issue.

The existing literature has focused mainly on the impact of fact-checking on voters, providing mixed evidence of its effectiveness in influencing voters' beliefs and attitudes towards ‘lying’ politicians (Zhuravskaya et al. 2017, Barrera et al. 2020, Swire et al. 2017, Nyhan 2020, Henry et al. 2020, Henry et al. 2021). Yet, the potential welfare consequences of fact-checking ultimately depend on how politicians respond to it. Indeed, voters' responses to fact-checking may be neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition to trigger a politician's reaction. On the one hand, politicians may react to fact-checking only if the effect on voters is sufficiently strong to induce electoral concerns, and such a response will likely be heterogeneous across politicians. On the other hand, even if electoral concerns and voters' reactions are meagre, politicians may still be responsive to fact-checking for different reasons. For example, negative fact-checking may harm a politician’s reputation and credibility since being negatively exposed may lower the politician's chances of entering party leadership or seeking higher office, or simply hurt the politician due to self-image concerns. As such, the risk of incurring negative fact-checking may increase the cost of lying in politics.

In a recent paper (Mattozzi et al. 2022), we tackle this question by investigating whether and how politicians react to a rigorous fact-checking of their political statements. Our analysis combines two unique elements:

- A randomised ‘business as usual’ field experiment, in collaboration with the leading Italian fact-checking company, Pagella Politica, allows us to overcome the potential biases arising from the endogenous selection of statements by fact-checkers.

- A difference-in-differences analysis focusing on political statements of treated politicians before and after fact-checking, compared to politicians who are not fact-checked, allows us to control for unobserved heterogeneity across politicians and over time.

Our study is based on a detailed dataset of political statements: the universe of statements publicly released by a sample of 55 Italian MPs over a period of 16 weeks (three pre-intervention, ten intervention, and three post-intervention) starting from March 2021. In the core part of the study (that is, during each intervention week), we first randomly select a politician among those in our sample who made at least one verifiable (i.e. fact-checkable) and incorrect statement during the previous week. Then, we randomly select one of these statements, which is rigorously fact-checked by our partner. Following the usual practice of the fact-checking organisation, the verdict is published on its webpage and on its social media pages (Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram). To maximise the effectiveness of the campaign, and to make sure treated politicians are aware of the fact-checking, Tweets advertising the fact-checking also mention the politician’s official Twitter account.

Figure 1 Example of fact-checking page and fact-checking tweet

Our results show that politicians respond to fact-checking. In the weeks after the fact-checking, fact-checked politicians reduce the number of incorrect statements by an order of more than one quarter of a standard deviation. This is the case both in terms of the absolute number of incorrect statements and as a share of fact-checkable statements. Noticeably, the effects of the treatment are not short-lived, lasting at least eight weeks.

It is important to remark that the randomisation of politicians’ statements to be fact-checked was made in the background. As such, our business-as-usual design did not alter the politicians' perception of the fact-checking process, so our results are likely to preserve a high external validity in other contexts. Furthermore, we test the robustness and external validity of our results by using a different dataset obtained from a pilot experiment run in November 2020. Interestingly, despite the different time-period and different set of politicians, the estimates that we obtain are remarkably similar between the two datasets. We also validate the causal interpretation of our estimates by providing a random-inference test. Specifically, we exploit the existence of a randomisation pool of politicians that could have been subject to fact-checking in a given week but were not.

Why do politicians respond to fact-checking? After all, politicians belonging to the treated and control group in a given period face the same probability of being fact-checked in the future. Furthermore, we do not find evidence that the treatment might have spillover effects across politicians in the same party or in the same party chamber; that is, politicians in the control group do not respond to fact-checking on a party peer. This suggests that fact-checking does not operate through a simple information channel (e.g. making politicians aware of being potentially fact-checked or increasing the salience of fact-checking per se). Rather, fact-checking seems to have a specific direct impact on the treated politician.

We can think of three possible narratives that rationalise the observed behaviour. First, politicians might have convex costs from being repeatedly exposed to negative fact-checking. This could be due either to self-image or to career concerns, or it might be related to voters becoming progressively less forbearing with politicians repeatedly making false statements. This narrative is consistent with the fact that we observe more significant effects for politicians who have been fact-checked in the past as compared with ‘rookies’ in the fact-checking department. An alternative narrative could be that treated politicians revise upward their perceived probability of being fact-checked in the future. Unfortunately, we do not have direct evidence to test this hypothesis. Yet, one would expect that such updating might be stronger for ‘rookies’, which runs contrary to the evidence we observe. Finally, fact-checking might have a behavioural impact on politicians by priming normative concerns against lying (Nyhan et al. 2015, Cohn and Marechal 2016). This mechanism is consistent with the stronger response observed among politicians who received worse fact-checking scores.

A related question is whether the observed behaviour is due to politicians' electoral concerns or a direct response that does not reflect a concern for voters' reactions. We find mixed evidence on this. Politicians elected in single-member districts, where electoral accountability has more bite, are the most responsive to fact-checking. Yet, we also observe a significant response by fact-checked politicians elected in multi-member districts. As the electoral fate of such politicians very much depends on party choices (where and how to place them on the ballot), such evidence suggests that career concerns (inside and/or outside the party) or self-image concerns (Bursztyn and Jensen 2017) could play an important role.

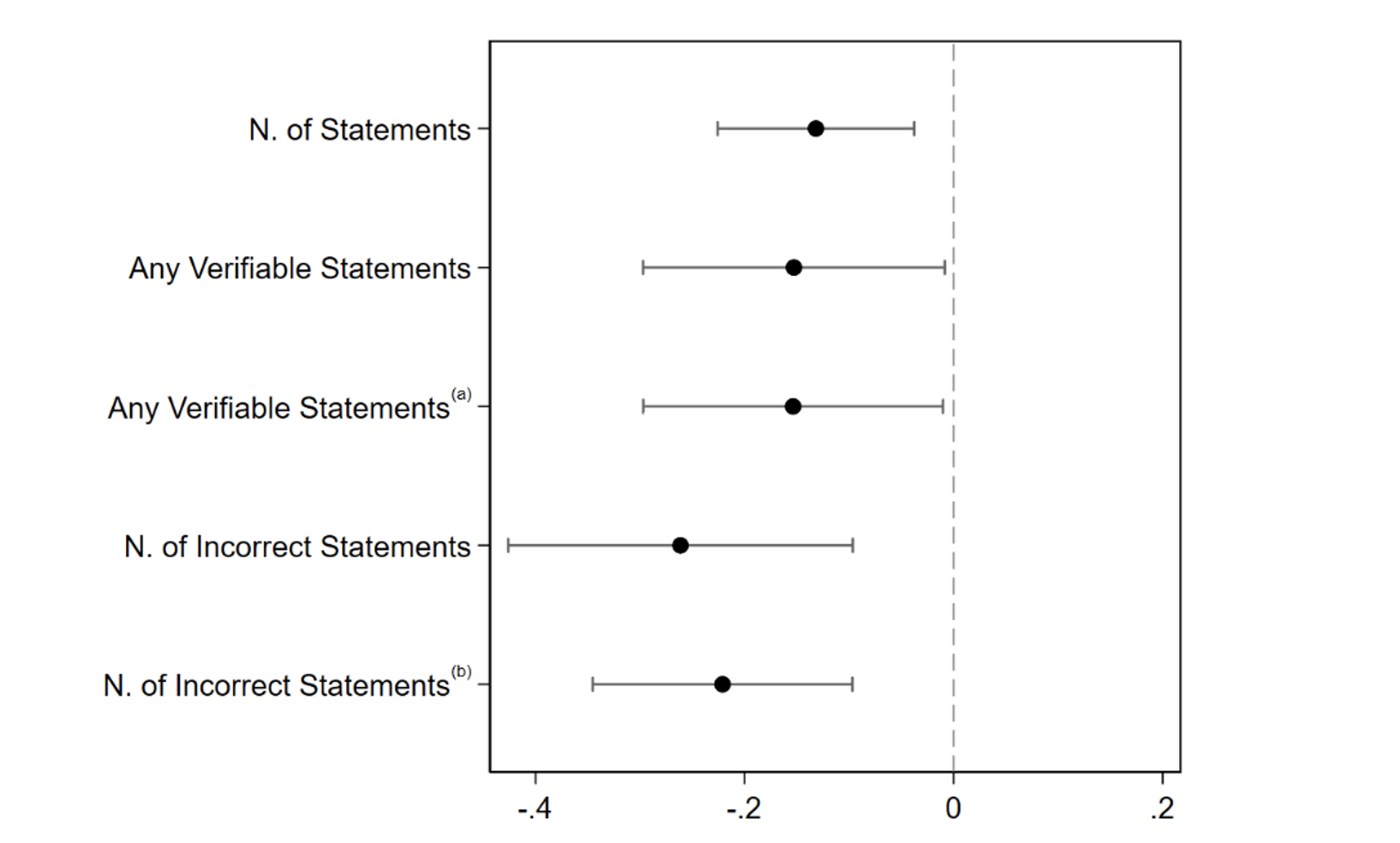

Finally, turning our attention to other observed measures of politicians' behaviour, we find evidence that treated politicians reduce their overall number of weekly statements and, importantly, the probability of making any verifiable statement. These findings suggest that politicians exposed to negative fact-checking also respond by resorting to non-factual claims or vacuous political rhetoric; that is, they also increase the ‘ambiguity’ of their statements. Figure 2 provides a graphical summary of the impact of fact-checking on the main outcomes of interest.

Figure 2 Effect of fact-checking on the main outcomes of interest

Notes: The number of statements and the number of incorrect statements are standardised variables. Confidence intervals at the 90% level, (a) controlling for the politicians making any statement in a week and (b) controlling for the number of verifiable statements made by a politician in a week.

All in all, our results show that fact-checking discourages politicians from making factually incorrect statements, with effects lasting for months. Since fact-checking is conducted on a regular basis, with a frequency that typically increases during electoral campaigns, our results provide the first evidence that fact-checking is indeed an effective tool in reducing the level of ‘factual misinformation’ in politics. At the same time, we also document some unexpected drawbacks, since fact-checked politicians are less likely to make verifiable statements. This suggests that they deliberately increase the ‘ambiguity’ of their language to escape the possibility of public scrutiny.

References

Barrera, O, S Guriev, E Henry and E Zhuravskaya (2020), “Facts, Alternative Facts, And Fact Checking in Times of Post-Truth Politics”, Journal of Public Economics 182: 104123.

Bursztyn, L and R Jensen (2017), “Social Image and Economic Behavior in The Field: Identifying, Understanding, And Shaping Social Pressure”, Annual Review of Economics 9: 131–153.

Cohn, A and M A Marechal (2016), “Priming In Economics”, Current Opinion in Psychology 12: 17–21.

Henry, E, E Zhuravskaya and S Guriev (2020), “Fact-checking Reduces the Propagation of False News in Social Networks”, VoxEU.org, 21 May.

Henry, E, E Zhuravskaya and S Guriev (2021), “Checking and Sharing Alt-Facts”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Mattozzi, A, S Nocito and F Sobbrio (2022), “Fact-checking Politicians”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17710.

Nyhan, B and J Reifler (2015), “The Effect of Fact-Checking on Elites: A Field Experiment on Us State Legislators”, American Journal of Political Science 59(3): 628–640.

Nyhan, B (2020), “Facts And Myths About Misperceptions”, Journal Of Economic Perspectives 34(3): 220–36

Swire, B, A J Berinsky, S Lewandowsky and U K Ecker (2017), “Processing Political Misinformation: Comprehending the Trump Phenomenon”, Royal Society Open Science 4(3): 160802.

Zhuravskaya, E, S Guriev, E Henry and O Barrera (2017), “Fake news and fact checking: Getting the facts straight may not be enough to change minds”, VoxEU.org, 2 November.