Many countries have implemented strict containment measures such as social distancing and stay-at-home policies to deal with the spread of COVID-19 (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020). Such measures have required many workplaces to shut, with most of the labour force obliged to stay at home. While lockdowns practically forced many people to stop working, others were able to continue working remotely from home, at least partially, sometimes with almost no activity reduction.

While working from home represents an opportunity to reduce the economic costs of lockdowns and social distancing measures, not all occupations are suitable for remote working. Even more importantly, the possibility for remote working is not the same across locations within countries. As shown by Dingel and Neiman (2020), the first authors to study how remote working can differ across locations in the US, a much larger share of employment is able to shift to remote mode in some places than in others, reducing the economic costs of lockdown more significantly in those regions.

Our study (OECD 2020) assesses the potential of remote working within 27 EU countries, Switzerland, Turkey and the US. Overall, cities – especially capitals – have a higher share of employment that can potentially be done via teleworking than other places within the same countries. This share is, on average, 15 percentage points higher in the region with the highest potential for remote working than in the region with the lowest potential, reaching more than 20 percentage points in certain countries. The concentration of occupations that have a high remote working potential in some regions drives these large within-country differences.

Assessing remote working potential through a classification of occupations

To assess regional differences in remote working potential, our study exploits the diversity of tasks performed in different types of occupations and the geographical distribution of those occupations. The assessment of remote working potential across regions consists of two steps. The first step uses the classification of occupations developed by Dingel and Neiman (2020) for the US to determine the degree to which each occupation is amenable to telework. This classification is built from the O*NET surveys conducted in the US that measure the extent to which the task content of each occupation can be performed at home. For example, occupations requiring workers to be outdoors (e.g. food delivery) or to use heavy equipment (e.g. a vehicle) are considered to have a low potential for remote working. In contrast, occupations requiring only a laptop and an internet connection (accountant, finance specialist, etc.) will have a high potential for working remotely. In the second step, using individual-level observations from labour force surveys, we assess the geographical distribution of different types of occupations and match those occupations with the classification performed in the first step. Combining the two data sets allows us to assess the number of workers that can potentially perform their tasks from home as a share of the total employment in the region.

Cities have a larger share of people that can work remotely

The potential for remote working varies greatly both between and within countries. Across countries, 50% of the employed population can work from home in Luxembourg, the highest share in our sample, while only 21% can do so in Turkey. Looking at individual regions reveals that capitals have, in most cases, the highest share of employment in occupations that can potentially be performed remotely (Figure 1); this share is 9 percentage points higher in capital regions than in their respective country taken as a whole, on average.

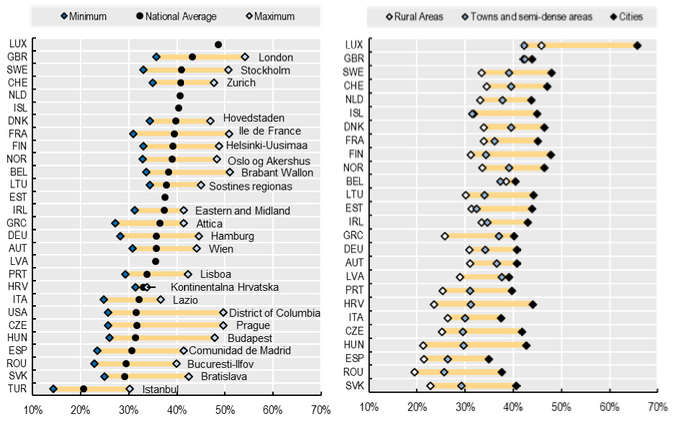

Figure 1 Potential for remote working between and within countries

Share of jobs that can potentially be performed remotely (%), 2018, NUTS-1 or NUTS-2 (TL2) regions

Note: The number of jobs in each country or region that can be carried out remotely as the percentage of total jobs. Countries are ranked in descending order by the share of jobs in total employment that can be done remotely at the national level. Regions correspond to NUTS-1 or NUTS-2 regions depending on data availability. Outside European countries, regions correspond to Territorial Level 2 regions (TL2), according to the OECD Territorial Grid.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Labour Force Survey, American Community Survey, Turkish Household Labour Force Survey and Occupational Information Network data (accessed in April 2020).

Overall, as shown in Figure 1, regional differences in potential remote working are stark. Within countries, the share of employment that can work remotely is 15 percentage points higher, on average, in the region with the highest share than in the region with the lowest share. This difference reaches more than 20 percentage points in the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, and the US, driven in large part by high levels of potential for remote working in capital regions.

A more general pattern revealed by our study is that potential for remote working is higher in cities and, more generally, in densely populated areas. Using the ‘degree of urbanisation’1 to distinguish different types of settlements for European countries, cities (above 50,000 inhabitants) have a 13-percentage point higher share of jobs suitable for remote working than rural areas (Figure 1). This urban-rural gap is particularly significant in Croatia, Finland, Hungary and Luxembourg. Interestingly, for towns and semi-dense areas, the potential for remote working seems to be somewhat closer to that of rural areas than to that of cities.

The remote working potential of a region reflects the skills of its labour force

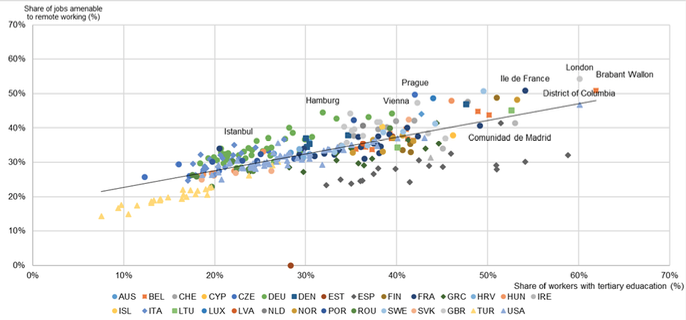

Within-country differences in the potential for remote working depend on the distribution of certain occupations across space. For example, a large proportion of management jobs, where almost 70% are expected to be able to work remotely, will be reflected in a higher remote working potential. In contrast, a large share of elementary occupations will drive the potential for remote working down. This mechanism underlies a clear fact emerging from our study that within-country differences in remote working reflect the education level of the regional workforce. This is shown in Figure 2, which plots a strong – and statistically significant – relationship between regions’ levels of potential for remote working (vertical axis) and their share of workers with a tertiary education (horizontal axis). This relationship is somewhat nuanced by country-level characteristics – some countries are consistently above (e.g. Germany) or below (e.g. Spain, Turkey) the interpolating line – possibly indicating the role of the industrial composition, potential over-qualification or other specific features of national labour markets.

Figure 2 Potential for remote working increases with skill levels in the region

Share of jobs that can be performed remotely (%) and workers with tertiary education (%), in 2018

Note: The number of jobs in the region that can be performed remotely as the percentage of total jobs (vertical axis), and the share of workers with tertiary education in total workforce (horizontal axis). Regions correspond to NUTS-1 or NUTS-2 regions depending on data availability. Outside European countries, regions correspond to Territorial Level 2 regions (TL2), according to the OECD Territorial Grid.

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Labour Force Survey, American Community Survey, Turkish Household Labour Force Survey and Occupational Information Network data (accessed in April 2020).

To interpret these findings more appropriately, it is worth noting that the findings assume that workers in all regions and countries have access to a good internet connection, which is necessary for remote working. The actual numbers of workers that can work from home will depend on the existence and the quality of internet connections in the region, and on the availability of the necessary equipment for workers. In that sense, the assessed potential for remote working should be considered as an upper bound given the current occupation structure. Regions that have low levels of digital infrastructure, such as certain rural areas, may not be able to exploit their capacity for remote working (OECD 2019). Consequently, the rural-urban divide in actual remote working may even be higher than the already large gap in potential remote working documented in our study.

The possibility of remote working offers a source of resilience to cities

The share of jobs that are suitable for remote working is an essential element in a region’s capacity to function under a lockdown or social distancing conditions. While large cities can suffer from a faster spread of the virus due to higher population density (Stier et al. 2020) and from greater specialisation in sectors that are particularly hard hit by lockdowns (OECD 2020), a higher potential for remote working can provide them with a source of resilience to the economic shock of the COVID-19 crisis. Still, both individual constraints – such as a lack of necessary equipment or working environment – and place-based constraints – such as the availability of a high-speed internet connection – can affect the capacity for people and firms to seize the opportunity of remote working. From a policy perspective, it is therefore important to use a place-based perspective to account for the specific opportunities and constraints that different types of regions face.

References

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (eds.) (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, a VoxEU eBook, CEPR Press.

Dingel, J and B Neiman (2020), “How Many Jobs Can be Done at Home?”, Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers 1: 16-24.

Eurostat (2013), “Urban-Rural typology”.

OECD (2020), “Capacity for remote working can affect shutdowns’ costs differently across places”, OECD COVID-19 Policy Note.

OECD (2020), “COVID-19: Protecting people and societies”.

OECD (2019), OECD Regional Outlook 2019: Leveraging Megatrends for Cities and Rural Areas.

OECD and EU (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation.

Stier, A, M Berman and L Bettencourt (2020), “COVID-19 attack rate increases with city size”.

Endnotes

1 The degree of urbanisation is a methodology to classify cities, towns and semi-dense areas, and rural areas for international comparative purposes. The method proposes three types of areas reflecting the urban-rural continuum instead of the traditional urban–rural dichotomy (Eurostat). A recent global application of the definition is made in (OECD and EU 2020).