The COVID-19 crisis, which caused almost 60,000 people lose their lives in a matter of months, could not have come at a worse time for Turkey. It was a time of mounting economic and political tensions. While the country was still struggling to overcome the adverse effects of the recession of 2018, in the early months of 2020 a major counteroffensive against the Syrian government was launched. This was followed by a stand-off with the EU in no longer conforming to the 2016 deal with Brussels to stop refugees leaving Turkey for Europe.

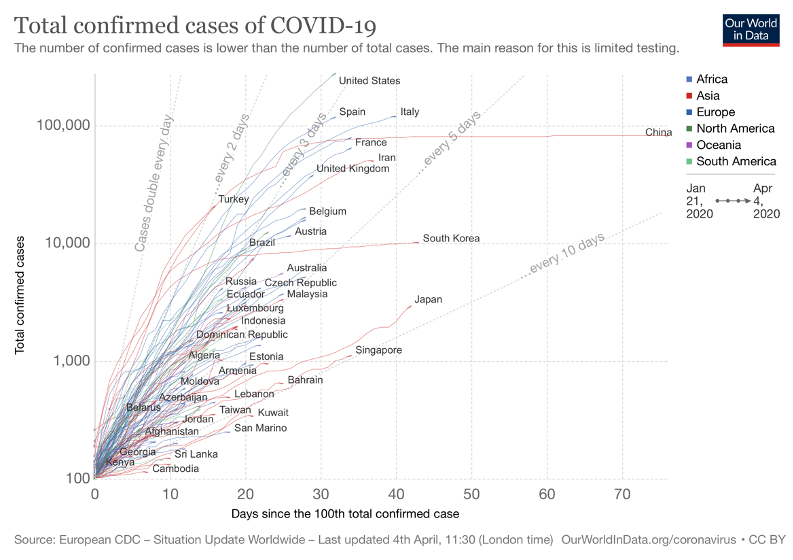

Then came the 10th of March, when the first confirmed COVID-19 case was announced in Turkey. From that day on the number of cases has grown rapidly, over 20,000 as of 3 April. This number is higher than the confirmed cases reported by any other country at the same stage of their outbreaks, i.e., 15 days since the 100th case (Figure 1). Sadly, 425 people have lost their lives in a matter of days.

Figure 1 A comparative view of COVID-19 cases in Turkey

Turkey has not adopted a nationwide lockdown yet. However, there are strict restrictions to entry and exit in 31 out 81 provinces. A plethora of containment measures including but not limited to compulsory quarantines for incoming passengers to Turkish airports presenting coronavirus risks, extensive travel bans and restrictions at international and intercity scales, closures of schools and universities, cancellation of public events, closures of public spaces and a complete curfew for people aged over 65 and under 20 (not including working youth) are now in place.

Furthermore, on 18 March, the government announced a 100 billion TL (approximately $15 billion) fiscal package called the "Economic Stability Shield Program" to alleviate the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak in Turkey. Neither the size nor the breadth of the programme in terms of its capacity to shield the ordinary people from the COVID-19 shock was found sufficient by different segments of the society. As a result, the key regulatory institutions in Turkey have adopted a series of money and capital markets measures as a response to mitigate the anticipated extraordinary strain of the outbreak on the Turkish economy.

Meanwhile it has been all quiet on the Syrian refugee front

Right before the COVID-19 outbreak, the Syrian refugee problem was at the top of the national agenda. Considering that Turkey hosts more registered Syrian refugees than any other country in the world, there is a deafening silence in regards to the refugees both in the rescue packages of the government and the major media outlets in Turkey in the recent weeks.

Two conjectures come to mind. First, Turkey has already granted the refugees free access to public healthcare and strengthened its capacity with new primary healthcare facilities in refugee-intensive provinces (Yılmaz 2019). Due to the national treatment of refugees in terms of these benefits offered by the state, a further need to address the problems of refugees in the COVID-19 crisis may not have been felt yet.

Second, there may be political and social concerns about bringing the matter to the surface. If containment efforts fail in large proportions, the healthcare system of Turkey bears the risk of not being able to withstand the burden. In such a scenario, when people are competing for healthcare, the previous decision of granting equal treatment to refugees may become a heavy political liability for the current government. In this likely scenario, there are societal risks involved as well. It is not unthinkable to observe rising xenophobia and its immediate disruptions in the society. In other words, the silence in regards to refugees may be a part of the political and social risk management by the involved parties.

If these were the true reasons, the first would be short-sighted and the second would be ill-advised when the current state of the Syrian refugees and the associated risks are considered.

Syrian refugees in Turkey

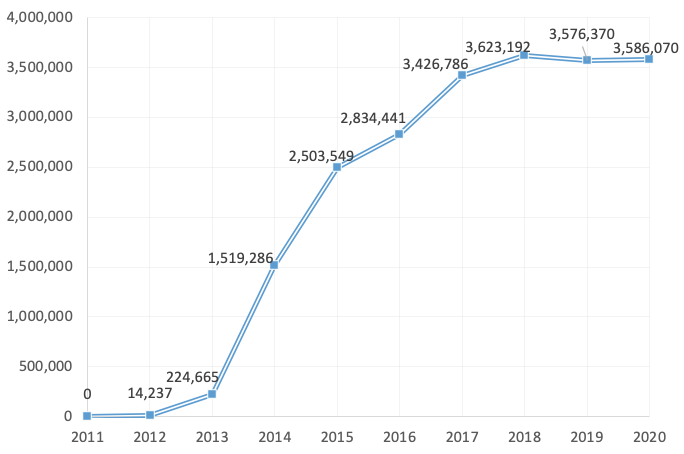

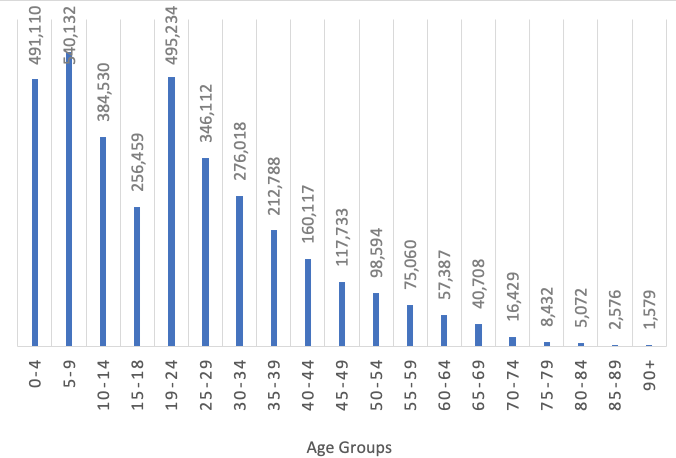

Since the beginning of the conflict in 2011, nearly 5.5 million Syrians have fled their country and sought refuge in nearby countries. The General Directorate of Migration Management in Turkey reports there are 3.6 million registered Syrians as of 26 March 2020 (Figure 2) with a legal status of “under temporary protection”. The refugees are overwhelmingly young; 2.5 million are under 30 years of age (Figure 3). Almost half a million children were born in Turkey.

Figure 2 The evolution of the mass Syrian migration to Turkey

Note: These numbers reflect the registered Syrian refugees with the temporary protection status. 2020 figures are as of March 26, 2020.

Data Source: The Directorate General of Migration Management (https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27)

Figure 3 Age distribution of Syrian refugees under temporary protection (as of 26 March 2020)

Data Source: The Directorate General of Migration Management (https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27)

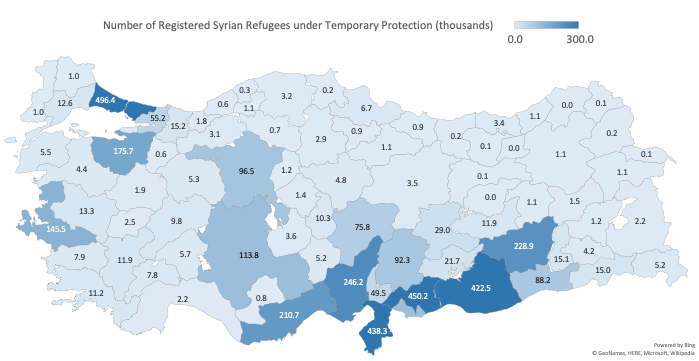

Figure 4 Geographic distribution of Syrian refugees under temporary protection (as of 26 March 2020)

Data Source: The Directorate General of Migration Management (https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27)

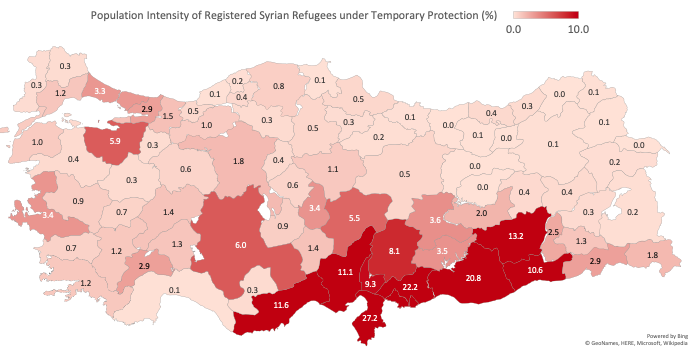

Figure 5 Population intensity of Syrian refugees under temporary protection (as of 26 March 2020)

Data Source: The Directorate General of Migration Management (https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27)

Only about 64,000 of the 3.6 million live in refugee camps mostly located in the southeastern provinces of Turkey. An overwhelming majority of Syrian refugees are outside the camps and spread across Turkey’s 81 provinces. Figure 3 illustrates the geographical distribution in terms of plain numbers, while Figure 4 shows the population intensity at the province level again as of 26 March 2020. The southern provinces of Şanlıurfa, Gaziantep and Hatay along with İstanbul, each have nearly half a million Syrian refugees. However, as expected, population intensity is much higher in the border provinces compared to İstanbul. The share of Syrian refugees under temporary protection in Şanlıurfa, Gaziantep, Hatay and Kilis, for example, is 21%, 22%, 27% and 78%, respectively.

There are a number of geographically heterogenous risks associated with the precarious lives of the refugees

First, Syrian refugees suffer from a lack of stable job opportunities. Informality is rampant. Many men have a hard time to secure a job or have to accept lower wages or – worse – work in hazardous conditions to make a living. Women’s labour force participation is tragically low at 9%. Cuevas et al. (2019) report that 45% of the Syrian refugees live in poverty and 14 percent live under extreme poverty. About 25% of children younger than five years of age are malnourished.

Second, any virus can spread widely in poorer areas. Crammed in tight spaces in the refugee camps with limited water or sewage hook-ups, frequent handwashing and social distancing can be very difficult. Not only in camps but also in large cities like İstanbul or Şanlıurfa, refugee families tend to live in homes with poor water, sanitation and hygiene conditions. The 2019 report by the Doctors of the World features that one in five refugees does not have access to clean drinking water and one in three does not have access to hygiene items in Turkey.

The refugee camps are located in border provinces. Furthermore, refugees not sheltered in the camps constitute a large percentage of the population of the southeastern provinces. Against this background of sub-standard living conditions, an outbreak among the refugee populations in these places can be very hard to control once it starts. In that case, not only the refugees themselves but also the remaining parts of the population in these provinces can become vulnerable to high rates of COVID-19 spread in their communities.

Last but not least, even before the COVID-19 crisis, Syrian refugees have had considerable healthcare needs owing to the long-term effects of the conflict. The vulnerability to health risks were high due to the trauma of the war and poor living conditions. Chronic diseases, physical injuries and severe psycho-social problems were widespread in the Syrian refugee populations. Due to the age composition (Figure 3), maternal and child healthcare needs were very high. However, even under those circumstances, the results of the Doctors of the World (2019) survey conclude that while 23% of the refugees do not have access to healthcare services in urban areas, this ratio shoots up to 58% in rural areas.

There are numerous barriers experienced by Syrian refugees in terms of their access to the free healthcare provided by the public healthcare facilities. Among these are language barriers, legal status issues, transportation costs to the nearest healthcare facility, lack of services coverage or information on available services.

As in other countries around the globe, the surge capacity of the healthcare system in Turkey is not enough to cope with a flood of tens of thousands of patients in a matter of days or weeks. Furthermore, as far as known so far, the novel coronavirus is typically most contagious when the symptoms are mild. In many of the severely disadvantaged refugee households in Turkey, no one will see a doctor until the condition gets serious enough to not be able to continue working to support the family. In other words, not having a concerted effort to inform the refugees about the dire consequences of the disease can have severe consequences for the speed of spread.

Considering all these risks leading to an umbrella risk of vicious pandemic cycles with ripple effects, turning a blind eye to the condition of the Syrian refugees in the COVID-19 crisis is an option neither for Turkey nor for the international community, because a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

A most needed moment of solidarity

In the upcoming critical days and weeks of the COVID-19 crisis management in Turkey, there are a multitude of tasks in front of the policymakers in terms of refugees: Basic health information on COVID-19 has to reach the refugees, which requires overcoming the language barrier and orchestrating a task force for this purpose. Helping hands have to be extended to the severely malnourished children. Unconditional cash transfers have to continue to alleviate extreme poverty and poor living conditions. Equal treatment right should not be abandoned under any circumstances. The success of all such measures have one elemental prerequisite though: Solidarity.

Derviş (2020) states that “[t]he COVID-19 crisis represents an unprecedented test of human solidarity.” The people of Turkey and the international community will certainly sit the same exam in the subject of Syrian refugees that are under temporary protection of Turkey.

Domestically, the political leaders from the ruling party to the opposition located at different echelons of the political landscape of Turkey have to very skillfully build solidarity across citizens and refugees. This is much easier said than done considering the major moral, economic and political fault lines that have appeared in the very fabric of a highly polarised society in the recent two decades.

Internationally, passing the solidarity test is even harder. In the time of severe human costs, border closures and deep economic crises, helping another country by sharing resources -financial or otherwise – will not be the knee jerk reflex for the policymakers around the globe.

The required reading list for policymakers to pass the test includes A Treatise of Human Nature by David Hume (1740), The Theory of Moral Sentiments by Adam Smith (1759), The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups by Mançur Olson (1965) and Liquid Modernity by Zygmunt Bauman (2000). The keywords to comprehend and then internalise are “moral sentimentalism”, “collective action”, “global public goods”, “social exclusion” and “privatisation of ambivalence”.

References

Bauman, Z (2000). Liquid modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

Cuevas, P F, O K Inan, A Twose and C Celik (2019). Vulnerability and Protection of Refugees in Turkey: Findings from the Rollout of the Largest Humanitarian Cash Assistance Program in the World. World Bank.

Derviş, K (2020) “The COVID-19 Solidarity Test,” Project Syndicate, March 31

Doctors of the World (2019). Multi-Sectoral Needs Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Turkey.

Hume, D (1740). A treatise of human nature.

Olson, M (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press.

Smith, A (1759). The theory of moral sentiments

Yılmaz, V (2019). “The Emerging Welfare Mix for Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The Interplay between Humanitarian Assistance Programmes and the Turkish Welfare System”, Journal of Social Policy 48(4): 721-739.