Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of firms and workers adopting working from home (WFH), or home-based remote work, increased substantially. Many firms have now moved away from remote work and back to working in the office, while some firms are planning to continue this workstyle into the future. The productivity of WFH is a key determinant in whether or not to continue this workstyle after the end of the pandemic.

Studies on the productivity of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic based on surveys of individual workers have been conducted in many countries, including Barrero et al. (2021) for the US, Etheridge et al. (2020) for the UK, and Morikawa (2022a) for Japan. However, these studies have produced very different results. Bartik et al. (2020) and Morikawa (2022a) are examples of studies using firm surveys. Bartik et al. (2020) reported that on average, WFH reduced productivity by approximately 20%, based on a survey of small and medium-sized businesses in the US. Morikawa (2022a) indicated that among Japanese firms, the mean productivity of WFH is about 68% of the productivity in their usual workplace. However, both surveys were conducted in the first half of 2020, and WFH productivity is likely to have changed through learning effects and related investments as the COVID-19 pandemic continued.

Analysing the dynamics of this work style using panel data is useful in evaluating the efficacy of WFH. Based on this understanding, I conducted a follow-up survey of Japanese firms in the fourth quarter of 2021 to extend the analysis of Morikawa (2022a). In this column, I document the main findings obtained from the panel data, focusing on the productivity of WFH (see Morikawa 2022b for details).

Change in WFH adoption and intensity

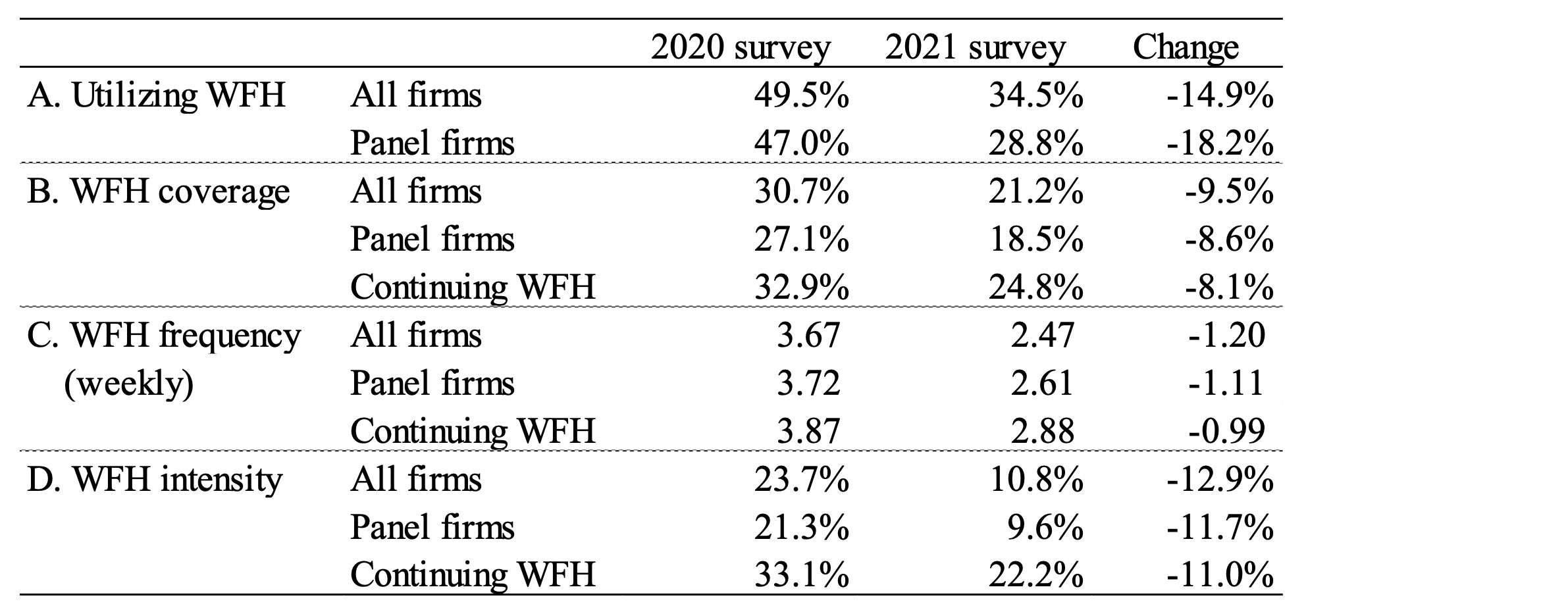

Table 1 compares the share of firms utilising WFH practices, coverage of remote workers, and mean frequency of WFH in 2020 and 2021. The percentage of firms adopting WFH (see Panel A) decreased by approximately 15 percentage points, from 49.5% in 2020 to 34.5% in 2021. When the sample was limited to panel firms that responded to the two surveys, the WFH adoption rate decreased from 47.0% to 28.8%.

However, even if a firm adopts the WFH practice, not all employees use this working style, and the coverage of remote work differs by firms. The mean percentage of employees engaged in WFH (see panel B) decreased from 30.7% in 2020 to 21.2% in 2021. When looking at the subsample of firms continuously utilising WFH practices, the coverage level was relatively high; however, it decreased from 32.9% in 2020 to 24.8% in 2021.

Even if an employee uses WFH, they do not necessarily work at home every working day. The mean weekly frequency of WFH (see panel C) decreased by 1.2 days, from 3.67 days in 2020 to 2.47 days in 2021. Even when limiting the sample to firms that are continuously adopting WFH practice, the mean frequency decreased by about a day, from 3.87 in 2020 to 2.88 days in 2021.

By multiplying the coverage of WFH employees by the frequency of mean WFH (expressed as percentages), we can calculate ‘WFH intensity’, which is the ratio of WFH hours to total working hours. The WFH intensity (see panel D) decreased significantly from 23.7% in the 2020 survey to 10.8% in the 2021 survey. But when limiting the sample to firms continuously utilising WFH practices, the reduction in WFH intensity is relatively small (from 33.1% to 22.2%) and the level of WFH intensity is relatively high even in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Table 1 Adoption and intensity of working from home

Notes: The WFH intensity (panel D) is calculated as the WFH coverage multiplied by the frequency of WFH per week (converted into percentage). Panel firms are those which responded to the 2020 and 2021 surveys. Firms continuing WFH are those adopting WFH practices in the 2020 and 2021 surveys.

To summarise, at the end of 2021, both the ratio of WFH adopting firms (extensive margin) and WFH intensity (intensive margin) decreased substantially compared to when the first state of emergency was declared in spring 2020.

Productivity of remote work

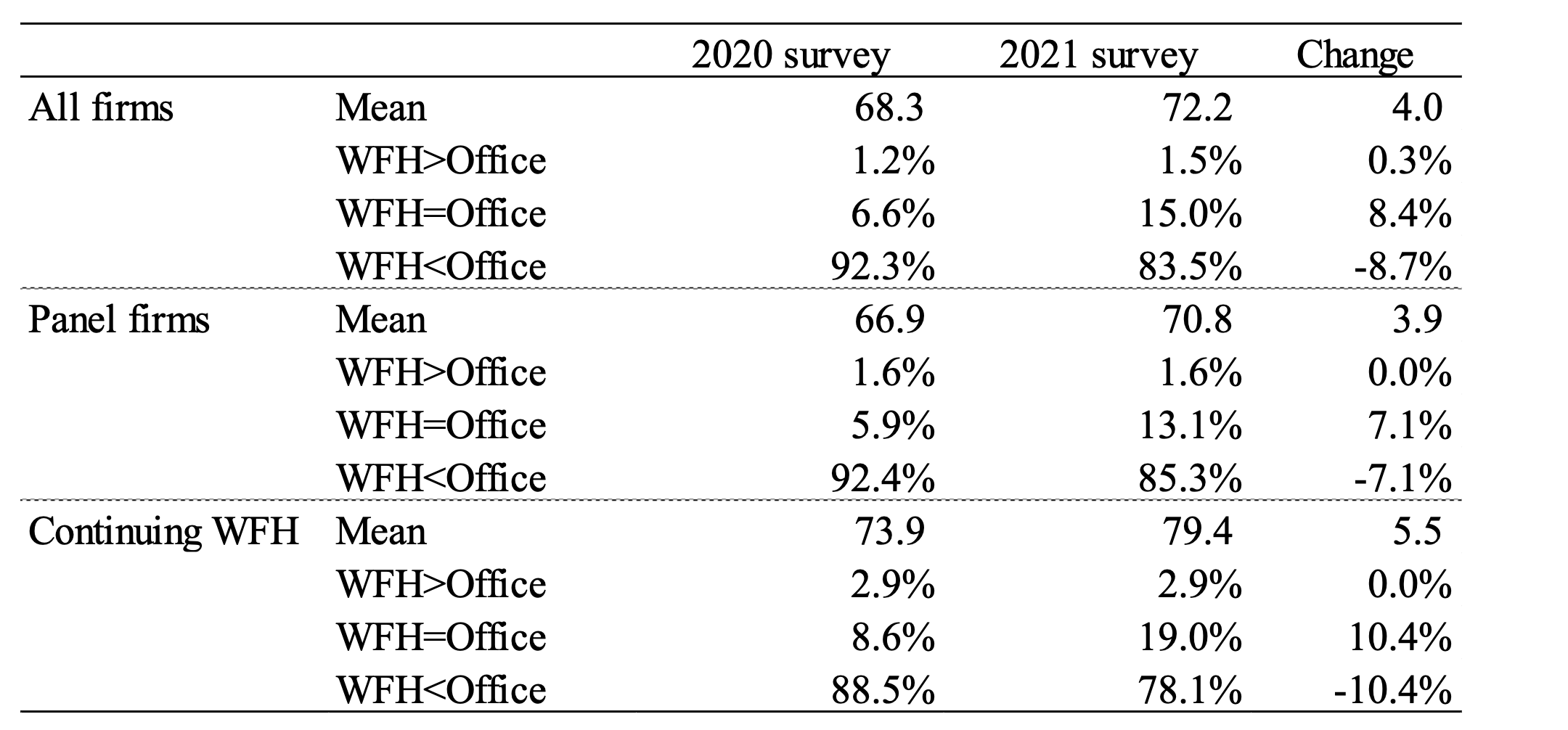

Table 2 reports the productivity of WFH in 2020 and 2021. The productivity of WFH is a firm’s subjective evaluation of their remote workers’ mean productivity at home relative to productivity at the office (=100). The mean WFH productivity of firms utilising WFH improved by about four points from 68.3 in the 2020 survey to 72.2 in the 2021 survey. When limiting the sample to firms that are continuously using WFH practices, productivity improved by about 5.5 points from 73.9 in 2020 to 79.4 in 2021. My interpretation is that the improvement in productivity of WFH continuing firms arises from the learning effect and redistribution of work within the firm, such as with returning employees and/or tasks with relatively low productivity from home to the office.

Table 2 Firms’ evaluation of WFH productivity

Notes: Mean WFH productivity is a subjective assessment of employee productivity at home relative to the office (=100). WFH>office, WFH=office, and WFH<office are percentages of firms. Work from home: WFH.

However, the mean evaluation of remote worker productivity at home is still approximately 20% lower than at the usual workplaces. When dividing the responses into WFH>office, WFH=office, and WFH<office, the percentage of firms that evaluated productivity at home as lower than the office was 92.3% in the 2020 survey and 83.5% in the 2021 survey. In the 2021 survey, the percentage of firms that stated that there is no difference in productivity between work at home and in the office increased slightly, but the majority of firms rated WFH as less productive than office work. The results suggest that there are technical and institutional factors that reduce the efficiency of WFH and that face-to-face information exchange is still important, even if various online communication tools have become available.

Remote work after the pandemic

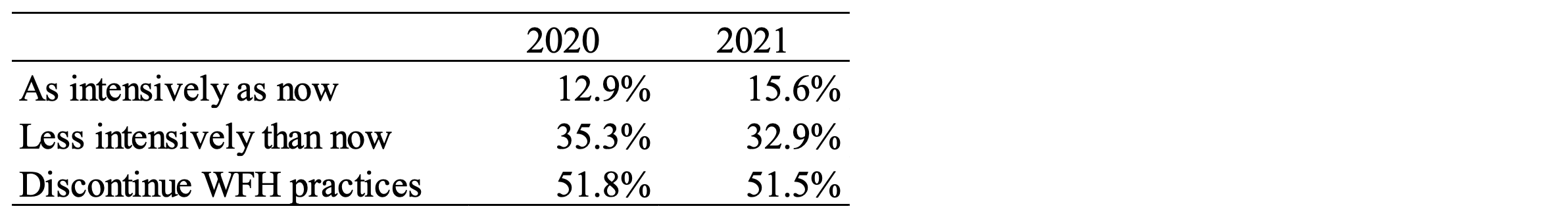

Table 3 presents the results on WFH adopting firms’ views of WFH after the pandemic. The percentage of firms that responded that they would use WFH practices as intensively as now was 15.6% in the 2021 survey, up slightly from 12.9% in 2020. Even for the subsample of continuing WFH firms, the change was small (from 20.8% to 22.8%). In both the 2020 and 2021 surveys, the majority of firms chose “discontinue WFH practices,” and more than 30% of firms intended to reduce the coverage of employees and/or the WFH frequency. These figures suggest that most Japanese firms are likely to reduce WFH once the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. Since the productivity of WFH is, at least on average, lower than in the office, firms’ intentions are unsurprising.

Table 3 Working from home after the COVID-19 pandemic

However, there is a large gap between employers and employees regarding the intention to use WFH practices after the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the findings from the employee survey (Morikawa 2021), the percentage of remote workers who want to continue frequent WFH is more than 60%, suggesting a non-pecuniary benefit or amenity value of WFH for remote workers. From the viewpoint of the balance between productivity and wages as well as the theory of compensating wage differentials, it is likely that the relative wages of remote workers will decline in the future.

However, in practice, it is extremely difficult to evaluate the productivity of individual remote workers accurately. Therefore, there will be serious conflicts between employers and employees regarding the use of WFH after the pandemic.

Editor’s note: The main research on which this column is based (Morikawa 2022b) first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Barrero, J M, N Bloom, and S J Davis (2021), “Why Working from Home Will Stick,” NBER Working Paper No. 28731.

Barrero, J M, N Bloom, S J. Davis, B Meyer and E Mihaylov (2022), “The Shift to Remote Work Lessens Wage-Growth Pressures,” NBER Working Paper No. 30197.

Bartik, A W, Z B Cullen, E L Glaeser, M Luca and C T Stanton (2020), “What Jobs are Being Done at Home During the Covid-19 Crisis? Evidence from Firm-Level Surveys,” NBER Working Paper No. 27422.

Etheridge, B, L Tang and Y Wang (2020), “Worker Productivity during Lockdown and Working from Home: Evidence from Self‑reports,” Covid Economics 52: 118–151.

Morikawa, M (2021), “Productivity of Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Panel Data Analysis,” RIETI Discussion Paper 21-E-078.

Morikawa, M (2022a), “Work-from-Home Productivity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Japan,” Economic Inquiry 60 (2): 508–527.

Morikawa, M (2022b), “Productivity Dynamics of Work from Home since the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from a Panel of Firm Surveys,” RIETI Discussion Paper, 22-E-061.