The growth in labour productivity – real output per hour worked – in the US slowed markedly around 2004. During the previous ten years, labour productivity in the business sector had risen at an annual average pace of more than 3%. Productivity received a boost from innovations in the production of digital information and communications technologies (ICT) and the spreading use of ICT across all sectors of the economy. Despite the apparent continuation of the digital revolution, productivity growth slowed to about 2% a year during 2004-2010 and then dropped to a paltry pace near just 0.5% during 2010-2016. Outside the US, labour productivity growth also declined in other advanced market economies.

If sustained, this sluggish pace would have dire consequences for future gains in living standards. Over long spans of time, increases in labour productivity are the fuel that boosts living standards and the main reason that material well-being is significantly higher today than 50 or 100 years ago. At a 2% pace, labour productivity would double every 35 years, while at a 0.5% pace, that doubling would take almost 140 years.

Economists have debated the reasons for the slowdown, though no consensus has emerged. Explanations generally fall into three categories. It is attributed to either supply-side accounts pointing to factors limiting the growth rate of potential output;1 demand-side stories highlighting inadequate demand or interactions between weak demand and sluggish growth of potential output;2 or, finally, measurement explanations arguing that the tools of economic measurement have not kept up with the digital revolution and that the slowdown is a figment of poor measurement.3

We suspect that this debate will not be resolved anytime soon. That being said, we want to refocus the discussion about measurement of the digital economy. While we agree that available evidence on mismeasurement does not provide an explanation of the productivity slowdown, we also believe that biases in measures of ICT are significant and that this mismeasurement has important implications for economic growth in the future. In particular, we argue that innovation is much more rapid than would be inferred from official measures and that these on-going gains in the digital economy make the productivity slowdown even more puzzling. At the same time, we believe that this continued technical advance could provide the basis for a future pickup in productivity growth.

Are we mismeasuring the digital economy?

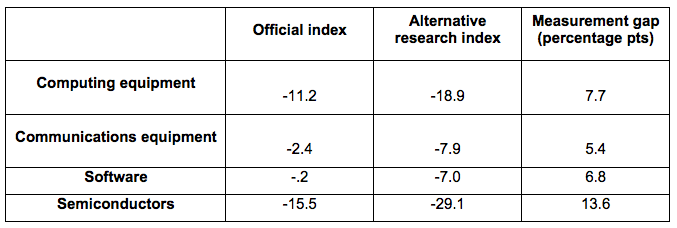

The short answer is yes. A key challenge to measuring changes in real GDP over time is correctly deflating nominal GDP to account for changes in prices. Getting price changes right for ICT production and investment is particularly difficult. And, as highlighted in Byrne et al. (2017), official measures of prices point to very slow rates of decline in the prices of high-tech products. But, a growing literature indicates that prices of ICT are actually falling much faster. For example, Byrne et al. (forthcoming) developed a new price index for microprocessors used in desktop computers. Their index fell at an average annual rate of 42% during 2009-13, while the most comparable official price index – the Producer Price Index – reports an average decline of 6% during the same period. Other research points to mismeasurement for other ICT products as well. Byrne and Corrado (2016) provide the best available measures of the amount of bias in official price indexes for high-tech products. Table 1 reports rates of change in official price indexes and the alternative research series for computers, communications equipment, software, and semiconductors reported by Byrne and Corrado (2016).4 As shown in the last column of the table, measurement gaps – which equal the difference between the percent changes of the official price index and the alternative research index – are sizeable for all of the high-tech products shown. Moreover, prices of many ICT products are still almost completely unstudied, including devices used in the medical, aerospace, and defence sectors and the industrial robots that have been the subject of much recent media attention.

Table 1 Official and alternative research price indexes for high-tech products, average percent change, 2004-2015

Note: Measurement gaps calculated as “official” less “alternative.”

Source: Byrne et al. (2017). Official indexes for computing equipment, communications equipment, and software are from the Bureau of Economic Analysis; the official index for semiconductors is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Alternative research indexes are from Byrne and Corrado (2016), including some details provided by the authors that are not reported in their paper.

In addition to ICT production, the digital economy encompasses an increasingly wide range of economic activity. The list is long and includes the myriad applications delivered by internet service providers, the energy exploration that relies on world class supercomputers to process seismic data, the surging e-commerce sector cannibalising shopping malls, the Hollywood movies produced with computer-generated imagery, the high resolution MRI, CT, and sonogram images that underpin advances in medical diagnosis, and many others. Developing price indexes that capture quality change for these industries is challenging. Moreover, the deep investment in ICT in all of the industries mentioned suggests that the official prices for their output, which in most cases show little change, may be missing something important.

Does this mismeasurement explain the productivity slowdown?

No. To explain the slowdown in labour productivity, either the amount of mismeasurement of productivity growth must have increased or the share of the mismeasured sectors must have risen. And recent research by Byrne et al. (2016) and Syverson (2017) has cast doubt on mismeasurement as an explanation of the productivity slowdown. While the amount of mismeasurement has increased in some areas, there was a lot of mismeasurement of high-tech before 2004 as well. And the production of many ICT products has shifted outside the US, reducing the GDP share of these products.

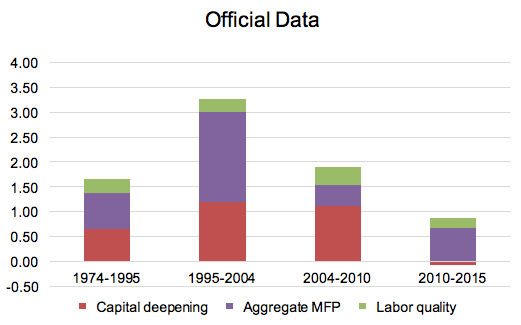

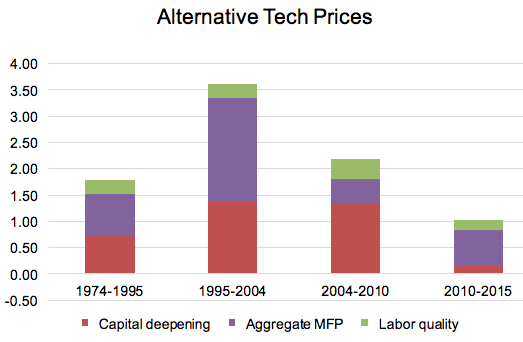

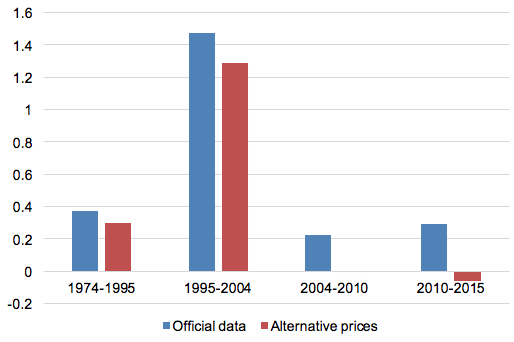

This answer was confirmed by Byrne et al. (2017). They use a detailed, multi-sector growth model to decompose growth in labour productivity into contributions from capital deepening (increases in the amount of capital available to each worker) and multifactor productivity (the amount by which output changes after accounting for changes in all inputs). Figure 1 shows this decomposition using both official price indexes (upper panel) and the alternative research price indexes described above (lower panel). As can be seen, switching from official price measures to the alternative research series has relatively little effect on the pattern of labour productivity growth over time, as well as the contributions from capital deepening and multifactor productivity (MFP). Byrne et al. (2017) focused on components of GDP that have been the subject of recent research attention. It is, of course, possible that mismeasurement elsewhere (either related or not related to the tech sector) could be biasing the pattern of labour and multifactor productivity in official measures.

Figure 1 Decomposition of labour productivity growth with official and alternative research prices, 1974-2015

Source: Byrne et al. (2017).

Does this mismeasurement matter?

Again, the answer is yes. Even though the mismeasurement of high-tech prices has little effect on the pattern of labour productivity growth across time, that mismeasurement has a dramatic effect on the allocation of MFP growth across sectors. As noted, MFP growth indicates the amount by which firms get better at transforming inputs into output. Along these lines, macroeconomists often use MFP growth as a rough proxy for the pace of innovation. MFP growth can be measured by comparing the growth rate of output to a weighted average of the growth rate of inputs. It also can be measured by comparing the price of output to a weighted average of changes in the prices of inputs (the so-called ‘dual’ approach). Borrowing the explanation from Sichel (2017), the logic of this approach can be seen in industries that experienced rapid technological progress. With fast MFP growth, an industry will be able, over time, to produce more output from a given set of inputs. If the cost of inputs is relatively stable, then those products should see their prices fall over time. For example, telecom has seen rapid price declines in recent decades. In 1952, a ten-minute daytime phone call from New York to Los Angeles cost about $48 in 2016 dollars.5 Today, phone companies do not even bother to separately price that call, and the call can be made from almost anywhere on a mobile phone rather than from a landline phone. These rapid price declines suggest that telecom experienced substantial growth in MFP.

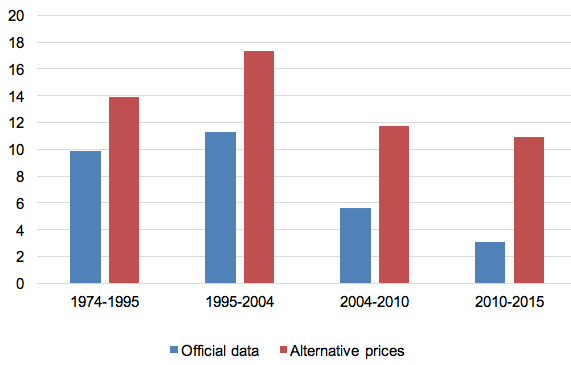

Byrne et al. (2017) use this dual approach to measure MFP growth in high-tech industries (which include the production of computers, communications equipment, software, and semiconductors). Figure 2 compares the estimates of MFP growth generated using official price measures (the blue cross-hatched bars) and the alternative research price indexes (the red bars). As shown, MFP growth in the high-tech sector is considerably more rapid using the alternative research prices. This pattern indicates that the innovation has been much faster in the high-tech sector than indicated by official measures and accords more consistently with casual impressions that the digital economy continues to be powered by ongoing advances.

Figure 2. Total tech sector MFP growth rates with official and alternative research prices, 1974-2015 (%)

Note: High-tech sector includes the production of computers, communications equipment, software, and semiconductors.

Source: Byrne et al. (2017).

Byrne et al. (2017) also use the dual approach to calculate the growth rate of MFP outside of the high-tech sector. As shown in Figure 3, these growth rates are much slower when the alternative research prices are used than when official measures are used. Thus, correcting the mismeasurement of high-tech prices leads to a reallocation of MFP growth across sectors toward high tech and away from the rest of the economy. This reallocation of MFP growth implies much faster innovation in the digital economy than implied by official measures.

Figure 3. Other output MFP growth rates with official and alternative research prices, 1974-2015 (%)

Source: Byrne et al. (2017).

A deeper puzzle, but hope for the future

This pattern of MFP growth makes the productivity slowdown even more puzzling. If the tech sector continues to innovate so rapidly, why has overall productivity growth been exceptionally sluggish? While it is possible that the challenges inherent in measuring output outside the ICT sector have suddenly worsened, we suspect that the answer depends importantly on the long lags necessary for innovations to diffuse through the economy and move the needle on overall productivity. This pattern of slow diffusion has been seen in the past both with electrification in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as for semiconductors in the second half of the 20th century. We believe that the faster rates of innovation in high tech that are evident, once measurement biases have been corrected, could be the fuel for a future pickup in productivity growth.6

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and not institutions with which they are affiliated. Sichel thanks the Bureau of Economic Analysis and National Telecommunications & Information Administration for financial support for related research on price measurement.

References

Branstetter, L, and D Sichel (2017), “The Case for an American Productivity Revival,” Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 17-26, June.

Byrne, D M, and C Corrado (2016), “ICT Prices and ICT Services: What Do They Tell Us about Productivity and Technology?” presented at CRIW/NBER Summer Institute.

Byrne, D M, J G Fernald, and M B Reinsdorf (2016), “Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2016(1): 109-182.

Byrne, D M, S D Oliner, and D E Sichel (forthcoming), “How Fast Are Semiconductor Prices Falling?” Review of Income and Wealth, also available as FEDS working paper 2017-005, January 2017.

Byrne, D M, S D Oliner, and D E Sichel (2017), “Prices of High-Tech Products, Mismeasurement, and the Pace of Innovation”, Business Economics 52(2(: 103-113.

Federal Communications Commission, Reference Book of Rates, Price Indices, and Household Expenditures for Telephone Service, March 1997.

Gordon, R J (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Economic Growth, Princeton University Press.

Mason, J W (2017), “What Recovery? The Case for Continued Expansionary Policy at the Fed,” Roosevelt Institute, July 25.

Reifschneider, D, W Wascher, and D Wilcox (2013), “Aggregate Supply in the United States: Recent Developments and Implications for the Conduct of Monetary Policy,” FEDS working paper no. 2013-77, November.

Sichel, D E (2017), “The Productivity Slowdown is Even More Puzzling than You Think,” Econofact, May 17.

Summers, L H (2014), “U.S. Economic Prospects: Secular Stagnation, Hysteresis, and the Zero Lower Bound,” Business Economics 49(2): 65-73.

Syverson, C (2016), “Challenges to Mismeasurement Explanations for the U.S. Productivity Slowdown,” NBER working paper 21974.

Endnotes

[1] See Gordon (2016) for one prominent version.

[2] Summers (2014) has written extensively about “secular stagnation” as an explanation. Mason (2017) and Reifschneider, Wascher, and Wilcox (2013) have argued that weak demand has restrained advances in potential output.

[3] For example, Goldman Sachs (2015 and 2016), argue that we are missing growth in key components of GDP, and Byrnjolfsson and Oh (2013) make the case that economic welfare is growing faster than real GDP.

[4] Note that the semiconductor index shown in the table incorporates the microprocessor index described above but also includes other semiconductors.

[5] For the cost in 1952, see Federal Communications Commission (1997: 62). The adjustment to today’s dollars was done with the price deflator for personal consumption expenditures.

[6] For a more complete explication of the case for a revival in US productivity, see Branstetter and Sichel (2017).