In corporate borrowing, courts can enforce creditors’ claims, including by requiring a firm to hand over assets to creditors. This enforcement mechanism provides some assurance of repayment, but it is weaker in sovereign debt for several reasons. First, when debt is issued under domestic law, judgments will be made by domestic courts, which might be biased in favour of the sovereign. Second, even when debt is issued under foreign law, there are legal barriers to collection such as sovereign immunity. Third, it is often impossible to enforce any court judgment because few sovereign assets are located in foreign jurisdictions.

For these reasons, the economic literature has emphasised that one key driver of sovereign risks is a country’s willingness (rather than ability) to pay its debt. According to this view, policies that increase the costs of defaulting on sovereign debt, even if inefficient ex post, can be efficient ex ante because, by increasing willingness to pay, they can facilitate access to international capital markets (Dooley 2000).1

One way for a government to reassure investors of its willingness to repay is to give them a priority claim to state assets, elevating investors over other potential claimants, including the country’s own citizens and residents (Cooley and Marimon 2011, Dove 2012, Moldogaziev et al. 2017). A few countries have enshrined such priorities in their constitutions. Consider Section 135.3 of the Spanish Constitution, controversially amended on 7 September 2011, which reads:

"Loans to meet payment on the interest and capital of the State’s Public Debt shall always be deemed to be included in budget expenditure and their payment shall have absolute priority. These appropriations may not be subject to amendment or modification as long as they conform to the terms of issue."

An interesting question is whether market participants believe that the government will keep its promise to prioritise public debt and thus value these commitments. The catch is that, in a crisis, politicians who prioritise financial creditors’ claims may not remain in office for long. Thus, Buchheit and Gousgounis (2019) suggest that these promises lack credibility because politicians may change or even ignore the law. But if these promises are not credible, they will not deliver any benefit in terms of lower yields, and could have costs as they may complicate things if the debt ever needs to be restructured.2

Priority promises around the world

In a recent work, we survey constitutions and fiscal laws of every country and identify 48 countries with legislative or constitutional provisions impacting the priority of public debt obligations (Gulati et al. 2019).3

We show that countries with these types of promises differ from the average country along many dimensions:

- they are more likely to be common law countries;

- they tend to have stronger protection of creditors’ rights;

- they tend to have higher levels of public debt; and

- they tend to have lower levels of inflation.

These findings suggest that countries that are more likely to face debt problems (as proxied by high levels of public debt) and that are less likely to wipe out the debt with high inflation are also the countries that are more likely to adopt priority promises.

Do these promises affect borrowing costs?

As the adoption of priority promises is non-random, a simple comparison of borrowing costs of countries with and without promises is likely to suffer from omitted variables and endogeneity biases. To address this issue, we focus on two within-country events. Specifically, we explore what happened around the adoption of the 2011 Spanish constitutional amendment described above and then focus on an event from 2018 which weakened a priority promise in a sub-sovereign borrower (Puerto Rico).

Spain

As mentioned, on 7 September 2011, the Spanish constitution was amended to confer super-priority on holders of the sovereign’s ‘public debt’. We compare sovereign bonds issued by the government itself to bonds issued by a large state agency, the Instituto de Crédito Oficial (ICO), which the government has guaranteed. Both types of bond represent a claim against state resources and hence should reflect country risk, but only sovereign bonds clearly meet Eurostat’s definition of ‘public debt’. Thus, although it is conceivable that the state-guaranteed debt might fall within the definition of ‘public debt’, there is serious doubt. If super-priority matters, this doubt should be reflected in yield spreads.

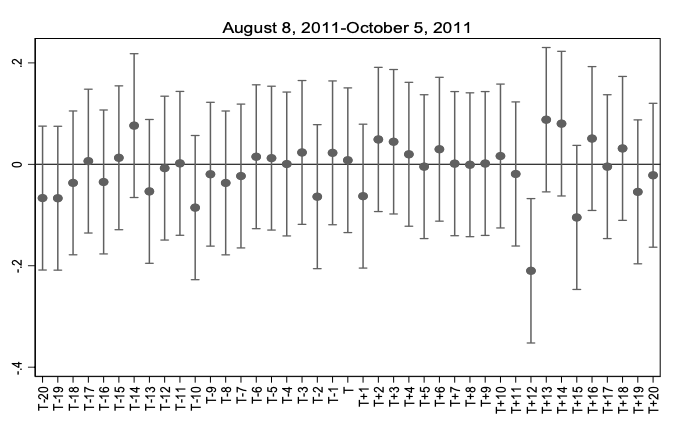

To test this hypothesis, we regress the change in sovereign yields over the change in ICO yields and a set of dummy variables that track what happened around the approval of the constitutional amendment. Figure 1 reports the results and shows that, conditional on ICO yields, the constitutional amendment had no effect on sovereign yields.4

While these results are consistent with the idea that the constitutional amendment had no effect on sovereign spreads, it is possible that this amendment was fully anticipated by the market and hence incorporated into sovereign yields well before the time window that we examine. We do not think this is the case because the result of the vote on the constitutional agreement was uncertain until the last few days before the vote and we find no effect in the four weeks prior to the amendment, including around the day (26 August; T-8 in Figure 1) on which the two largest Spanish parties agreed on the constitutional amendment.5

Figure 1 Daily changes in Spanish 10-year yields conditional on changes in ICO yields around the constitutional amendment of 7 September 2011

Notes: The dots are the point estimates of the daily changes and the whiskers are the 95% confidence intervals.

Puerto Rico

In Puerto Rico, we compare General Obligation (GO) bonds issued by the Commonwealth to bonds from COFINA, an entity set up by the Puerto Rican government to do borrowing explicitly backed by a first claim on the sales tax revenues of the Commonwealth. This comparison should work particularly well for our purposes because the first claim promised to COFINA bondholders conflicts with the constitutional priority enjoyed by holders of the government’s GO bonds.

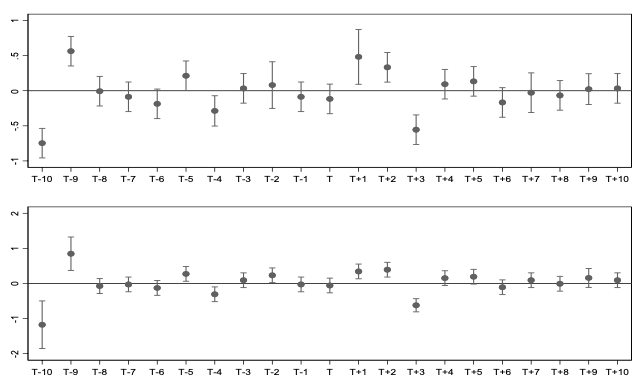

We focus on 30 January 2018, when the judge overseeing Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy proceeding dismissed a lawsuit by holders of GO bonds who were trying to establish their priority over COFINA bonds. If holders of general obligation bonds had previously viewed the constitutional pledge as credible, we should find that this decision increased the yield on Puerto Rico’s GO bonds conditional on the yields of the COFINA bonds.

We regress the change in yields of GO bonds over the change in yields of COFINA bonds and a set of dummies tracking the yield of GO bonds around the 30 January court decision. The top panel of Figure 2 shows that the yield of the GO bond index increased by approximately 100 basis points in the two days after the court decision, and then decreased by 50 basis points three days after. This result indicates that the court decision did lead to a repricing of Puerto Rico’s general obligation bonds with an effect of approximately 50 basis points in the three days that followed the decision (the results are robust to condition on the yields of the Government Development Bank, bottom panel of Figure 2).

Figure 2 Daily changes in Puerto Rico’s General Obligation Bonds conditional on changes COFINA Bond yields (top panel) and Government Development Bank yields (bottom panel) around the court decision of 30 January 2018

Notes: The dots are the point estimates of the daily changes and the whiskers are the 95% confidence intervals.

Summing up

Our tests suggest that the priority promise was credible in the case of Puerto Rico while it did not have any statistically significant effect on spreads in the case of Spain. One possible explanation for this finding is that, as Puerto Rico is a political subdivision of the US, supervening US federal law and federal institutions constrain it from reneging on its commitments. Spain, by contrast, could change or revoke the promise in accordance with Spanish law, making its priority promise less credible.

We have only examined two cases. But the lesson so far seems to be that these glorious promises to pay the holders of public debt before fulfilling any other obligations of the state should be viewed with caution in the case of sovereigns. They may, however, be meaningful for sub sovereigns.

References

Buchheit, L, B Weder di Mauro, A Gelpern, M Gulati, U Panizza and J Zettelmeyer (2013), “Revisiting sovereign bankruptcy,” VoxEU.org,12 November.

Buchheit, L and M Gousgounis (2019), “Nailing the flag to the mast—Promises of super-priority in public debt,” unpublished draft.

Cooley, T & R Marimon (2011), “A credible commitment for the Eurozone,” VoxEU.org, 11 July.

Dove, J A (2012), “Credible commitments and constitutional constraints: State debt repudiation and default in Nineteenth century America,” Constitutional Political Economy 23(1): 66–93.

Dooley, M (2000), “International financial architecture and strategic default: Can financial crises be less painful,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 53(1): 361–377.

Gulati, M, U Panizza, M Weidemaier and G Willingham (2019), "When governments promise to prioritize public debt: Do markets care?" CEPR Discussion Paper 13673.

Moldogaziev, T M, S M Kioko and B Hildreth (2017), “Impact of bankruptcy eligibility requirements and statutory liens on borrowing costs,” Public Budgeting & Finance, Winter: 47–73.

Panizza, U, F Sturzenegger and J Zettelmeyer (2009), "The economics and law of sovereign debt and default," Journal of Economic Literature 47(3): 651–698.

Endnotes

[1] For a discussion of these issues and policy proposals, see Buchheit et al. (2013). For a survey on the economics and law of sovereign debt, see Panizza et al. (2009).

[2] There are also political costs related to the approval of such laws which, in general, are not popular with voters.

[3] There are six countries that give explicit priority to repaying the debt and 42 countries with provisions to the effect that public debt claims will constitute a charge on the government’s consolidated or general funds.

[4] The results are robust to different windows and to controlling for the reactivation of ECB’s Securities Market Program (SMP) which happened in mid-August.

[5] One caveat with the analysis is that the constitutional amendment was passed in a period in which yields were high and volatile and the noise in the data might have swamped the signal of the amendment.