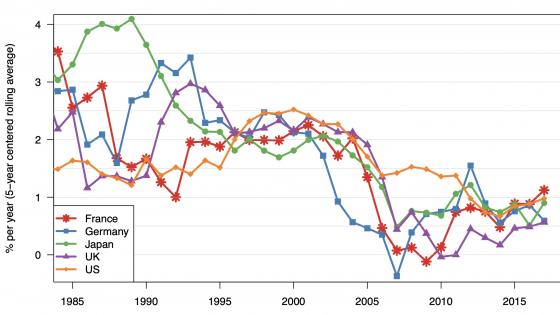

In the 15 years following the global crisis, UK growth fell to its lowest rate since the Great Depression. This was part of a broader decline in growth rates and interest rates in high income countries. Before the pandemic, there were concerns in several countries of a ‘secular stagnation’ trap, an idea revived by Larry Summers (Summer 2014).

Even before the UK economy recovered to its pre-pandemic level, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has introduced new headwinds to UK economic growth. The conflict has led to increases in energy and other commodity prices and threatens to fragment global supply chains. This risks additional constraints on global potential growth that may well be persistent.

The causes of low growth prior to the pandemic were hotly contested and it is still unclear how Covid and geopolitics will have exacerbated or mitigated the pre-Covid trends. Several studies have emphasised the longer-term structural drivers of weak growth. Gordon (2016) has argued that the pace of innovation at the frontier has been declining in the post-war period, and Bloom et al. (2020) provide evidence that the flow of new ideas has slowed significantly in recent years. There is empirical support for this idea, for example from Fernald (2016) who finds that growth at the (US) frontier slowed prior to the financial crisis. Fernald and Inklaar (2022) extend this work to a UK context.

Other researchers have emphasised the importance of the financial crisis in driving slower growth through prolonged weakness in demand. Blanchard and Summers (1986) argued that persistently elevated unemployment rates in the 1980s were due to ‘hysteresis’, whereby high unemployment leads to scarring effects and longer-term unemployment. Cerra et al. (2022) review the literature on hysteresis and related it to the global crisis. Recent research, including Fornaro and Benigno (2018), have emphasised the possibility of Keynesian ‘stagnation traps’ in which pessimistic expectations become self-fulfilling. A common thread in this work is growing evidence that challenges the assumption that macroeconomic policy only has a temporary impact on size of the economy. Ilzetzki (2022) gives evidence from WWII of the inverse phenomenon, whereby a high-pressure economy leads to higher productivity growth.

In a recent important contribution, Philippon (2022) argues that disappointing growth rates reflect unrealistic expectations rather than poor economic performance. He shows that total factor productivity (TPF) grows linearly, not exponentially, as previous research had asserted. Evaluated in this light, productivity growth rates can be expected to decline over time, as the level of TFP increments by constant amounts.

There are also more optimistic views on post-pandemic growth. For those who thought the original slowing was a structural phenomenon, the pandemic has spurred adoption of new technologies and working practices (see, for example, Valero et al. 2021). For those favouring more demand-side explanations, the aggressive response to the pandemic at home and abroad provides reason for thinking that economies may break away decisively from the low growth and low inflation of recent years.

While there is obvious uncertainty about the outlook, policymakers looking to drive a rapid recovery from the pandemic must confront this uncertainty and decide how best to raise living standards in the years ahead.

The May 2022 CfM survey asked the members of its UK panel to forecast the prospects for UK economic growth and propose policies that might improve the UK’s economic performance in the upcoming decade.

Question 1: How do you see prospects for future (per capita) GDP growth in the UK in the next decade?

Of the CfM-CEPR panel, 25 members answered this question. There is near unanimity (80% of the panel) that the UK will experience low growth over the upcoming decade. A majority of all respondents (56%) think this will be due to UK-specific structural challenges, while 20% believe that this will be because the world economy will underperform; a single respondent (representing 4% of the panel) thinks this will be due to weak demand. In contrast, 12% of the panel thinks the UK economy will experience high growth due to structural factors. Not a single panellist believes the economy would perform well due to strong demand.

The main local structural factors that will be a drag on the UK economic economy include Brexit and low levels of investment (both cited by several panellists). Richard Portes (London Business School and CEPR) adds an underperforming education system to the list and “impediments to research (e.g. destruction of research collaboration through EU Horizon programme and government indifference to science)”. Roger Farmer (University of Warwick) cites the green energy transition and an aging population as additional factors.

Michael Wickens (Cardiff Business School and University of York) predicts low growth due to global factors, but emphasises that domestic (monetary) policy might affect how badly the UK is affected: “The experience of the 1970's shows that it is better to take a short-term hit to growth to control inflation than to try to sustain demand in the face of a big supply shock. This is a lesson that seems to have been forgotten.”

James Smith (Resolution Foundation) is more concerned about weak demand in the medium term: “My worry in this context would be that the pandemic leaves us with lasting demand headwinds in the medium term (e.g. through planned tax rises or a deterioration in the terms of trade).”

Patrick Minford (Cardiff Business School) dissents from the majority view and believes that Brexit will be a boon for, rather than a drag on, economic growth: “The UK is moving into a new policy environment where it can regulate for innovation rather than for EU-style risk-avoidance. It is also able to open up the economy to world competition via new free trade agreements with the non-EU world.”

Question 2: What is the most important contribution economic policymakers can make growth in the UK over the next decade?

Of the panel, 27 members responded to this question. Thirty percent of the panel advocated for increased public investment and an additional 30% called for better trade relations with the EU or other countries. Fewer than 10% of the panel cited one of the following policies: repairing public finances, ensuring high levels of aggregate demand, or lowering inequality, as the best way to promote economic growth in the UK. It should be mentioned that most panellists believe that several, even all, these policy measures could and should be used to improve the UK’s economic performance.

Authors’ Note: This survey will provide context to the Economy 2030 Inquiry, a collaboration between the Resolution Foundation (RF) and the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) at the London School of Economics (LSE), and funded by the Nuffield Foundation, aims to address the question of how the policymakers can successfully navigate the decade ahead.

References

Bell, T, S Dhingra, S Machin, C McCurdy, H Overman, G Thwaites, D Tomlinson and A Valero (2021), “The UK's decisive decade: The launch report for The Economy 2030 Inquiry”, Resolution Foundation & Centre for Economic Performance, May.

Blanchard, O J and L H Summers (1986), “Hysteresis and the European Unemployment Problem”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1: 15–90.

Bloom, N, C I Jones, J Van Reenen and Michael Webb (2020), “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?”, American Economic Review 110: 1104-1144.

Cerra, V, A Fatás and S C Saxena (2022), “Hysteresis and Business Cycles”, Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.

Fernald, J G (2016), “Reassessing Longer-Run U.S. Growth: How Low?”, Working Paper Series 2016-18, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Fernald, J G and R Inklaar (2022), “The UK Productivity “Puzzle” in an International Comparative Perspective”, The Productivity Institute, Working Paper No. 020.

Fornaro, L and G Benigno (2018), “Stagnation Traps”, Review of Economic Studies 85: 1425-1470, July.

Gordon, R J (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living Since the Civil War, Princeton University Press.

Ilzetzki, E (2022), “Learning by necessity: Government demand, capacity constraints, and productivity growth”, LSE, March.

Philippon, T (2022), “Additive Growth”, NBER working paper 29950, April.

Summers, L H (2014), “Reflections on the new ‘Secular Stagnation hypothesis’”, VoxEU.org, 30 October.

Valero, A, C Riom and J Oliveira-Cunha (2021), “The business response to Covid-19 one year on: findings from the second wave of the CEP-CBI survey on technology adoption”, CEP Covid Analysis Series, No. 24, November.