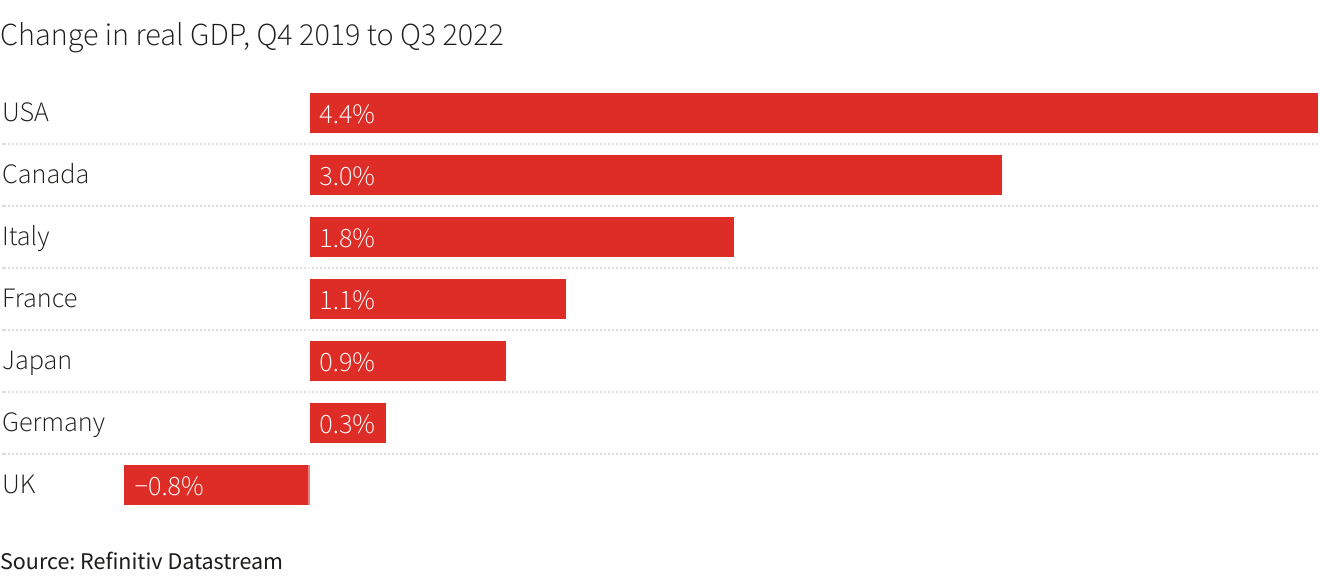

While the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukrainian crisis have been felt globally, there is widespread consensus that the UK has been the poorest-performing G7 economy. The OECD’s Economic Outlook report in November 2022 highlighted how UK growth has lagged behind the world’s largest economies since the COVID-19 pandemic and is substantially below the OECD average. Britain is the only G7 country yet to regain its pre-pandemic GDP levels.

Figure 1 Change in real GDP, Q4 2019 to Q3 2022

This gap is unlikely to shrink anytime soon. In January 2023, the IMF forecast that Britain would be the only leading economy likely to slide into recession this year. The IMF saw the UK as the only advanced economy to contract by 0.6% – worse even than Russia’s economic outlook. Similar forecasts were made by the Confederation of Business Industry, which stated that Britain runs the risk of seeing a “lost decade of growth” if action isn’t taken. The Resolution Foundation and the Centre for Economic Performance (2022) document these and other long-run trends in the UK’s relatively weak economic performance.

A possible factor underlying Britain’s slow recovery is its labour market. Amongst the OECD countries, only Latvia and Switzerland have seen bigger post-COVID-19 falls in employment than Britain. Currently, the UK is the only high-income country with employment rates below their pre-pandemic levels. While unemployment rates in the UK have been on a downward trend, the overall labour force has shrunk due to a combination of factors including long-term illness, lower migration rates, an increase in the number of students, and a rise in people taking early retirement.

According to the UK Office for National Statistics, the number of working-age adults who are out of the labour market (i.e. economically inactive) because of long-term sickness rose from 2 million in 2019 to 2.5 million in 2022. While this rise started before the pandemic, 363,000 people have become economically inactive due to long-term sickness since the pandemic hit the UK in 2020. According to Waters and Wernham (2022), one in ten people who developed long COVID stopped working, indicating that long COVID may have played a key role in reducing the UK workforce. Additionally, according to Institute for Employment Studies (2022), economic inactivity due to caring for family and home has also risen, after three decades of sustained falls.

Another big driver for the increase in economic inactivity amongst 16–64 year-olds is the rise in student numbers, with young people tending to start/stay in education instead of entering a tumultuous labour market. Furthermore, the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee indicated that early retirement by people in their 50s and 60s may have also been a leading cause for the rise in economic inactivity (Financial Times 2022).

However, Oulton (2019) argues that large increases in the labour force after 2007 reduced productivity growth in the UK relative to other comparable countries. If the opposite of this phenomenon were to also hold, then a decrease in the UK workforce could potentially have a positive effect on productivity growth, boosting Britain’s post-pandemic recovery.

Compared to other European countries, the UK has also been more significantly affected by rising energy prices from the Ukrainian crisis. According to Ari et al. (2022), the energy crisis hit household budgets in the UK harder than any other country in Western Europe, and the difference between the cost burden on poor and rich households was also far more unequal in the UK compared with other countries. With households already struggling after years of stagnating real wages, rising energy costs likely exacerbated the situation and decreased consumption in the UK, leading to lower growth. Higher energy bills have also increased the cost of doing business for UK firms, which were already facing increased volatility and change from Brexit and COVID-19 (Barnes et al. 2022).

One of the main reasons behind the UK’s higher vulnerability to global energy price hikes is its heavy reliance on gas to heat homes and produce electricity. In 2021, the UK relied on gas to produce more terawatt hours of electricity than any other European country, barring Italy. Another key difference between the UK and other European countries is the fact that UK houses are less energy efficient, forcing people to pay more for heating in the winter.

Brexit may also pose a continued drag on the UK economy. Brexit significantly increased trade costs for UK firms and decreased investment activity. Dhingra et al. (2016) investigated the potential impact on living standards in the UK and found that Brexit led to lower per-capita income across a range of possible scenarios. Freeman et al. (2022) disentangled the effects of COVID-19 and Brexit on UK trade and found that the implementation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement in 2021 led to a major disruption of UK-EU trade: UK imports from the EU fell by 25% (relative to the rest of the world) along with a sharp drop in the number of trade relationships between UK exporters and EU importers. Using a ‘doppelganger’/counterfactual UK model, Springford (2022) estimates that in the absence of Brexit, the UK economy would have been 5.2% bigger and goods trade 13.6% higher.

Furthermore, Dhingra et al. (2022) concluded that Brexit significantly disrupted UK supply chains, leading to a loss in UK trade openness and competitiveness as well as a loss in UK market share in both the EU and non-EU markets. Portes (2022) argues that this resulted in the UK missing out on the broad-based recovery in global trade volumes, which likely affected its post-pandemic recovery.

Investment levels in the UK have also significantly declined post-Brexit, contributing to the UK’s anaemic growth. The UK has ranked last amongst G7 members for investment growth since 2016, with business investment only now back to pre-pandemic levels and the level at the time of the 2016 Brexit referendum. This is in sharp contrast to other leading economies like the US, where business investment rose 24% from 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2022.

Springford (2022) reveals that in the second quarter of 2022, the UK shortfall in total investment due to Brexit was 13.7%. According to Haskel and Martin (2023), this has cost the UK 1.3% of its GDP in 2022, i.e. £29 billion. Moreover, the Peterson Institute for International Economics shows that between 2017 and 2020, average UK foreign direct investment inflows as a share of GDP plummeted to their lowest level since the 1980s.

Brexit also had a detrimental impact on the UK labour market due to a decrease in overall net immigration. Portes and Springford (2023) estimate that Brexit has led to a 1% reduction in the UK labour force (i.e. 330,000 people), primarily in low-skilled sectors. This has likely exacerbated Britain’s low labour supply post-pandemic, leading to a slower economic recovery.

Several economists and think tanks highlight long-term structural factors, predating the pandemic, that may have contributed to the UK’s stagnant growth and weak recovery. The February 2020 Centre for Macroeconomics survey (Ilzetzki 2020) revealed that most of the leading economists surveyed believed that low demand due to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent austerity policies has led to a slowdown in UK productivity, even before the onset of the pandemic. In the May 2022 survey (Smith and Ilzetzki 2022), the majority of the panel indicated that UK-specific structural issues would lead to low growth in the coming decade.

One such issue is the tendency of government policy after 2016 to ‘flip-flop’ from one idea to the next, according to Julian Jessop, a fellow at the free-market Institute of Economic Affairs. As a result, there has been a high degree of uncertainty, forcing companies to focus on staying afloat instead of building and expanding their businesses. Samiri and Millard (2022) also echoed these thoughts, characterising the constant shifts in policy as a ‘policy churn’, which make it impossible to assess the adequacy of existing policy and carry out the structural changes that can spur productivity in the long run.

Other issues include the inability of governments to resolve longstanding issues plaguing the UK’s feeble productivity. The UK lags behind other countries in important business skills and is also poorly placed in overall skills, ranking 51st between Romania and Armenia according to the Coursera Global Skills Report (Coursera 2022). Moreover, the UK still has a ‘long tail’ of companies with poor levels of output per hour worked but which neither seem to improve nor go out of business. Additionally, chronic underinvestment in public and business has contributed to low productivity and growth in Britain in post-2008 (Samiri and Millard 2022). Minford et al. (2022) show that tax cuts and regulatory reform could boost entrepreneurship substantially and thus catalyse economic growth.

Findings from the March 2023 Centre for Macroeconomics–CEPR survey

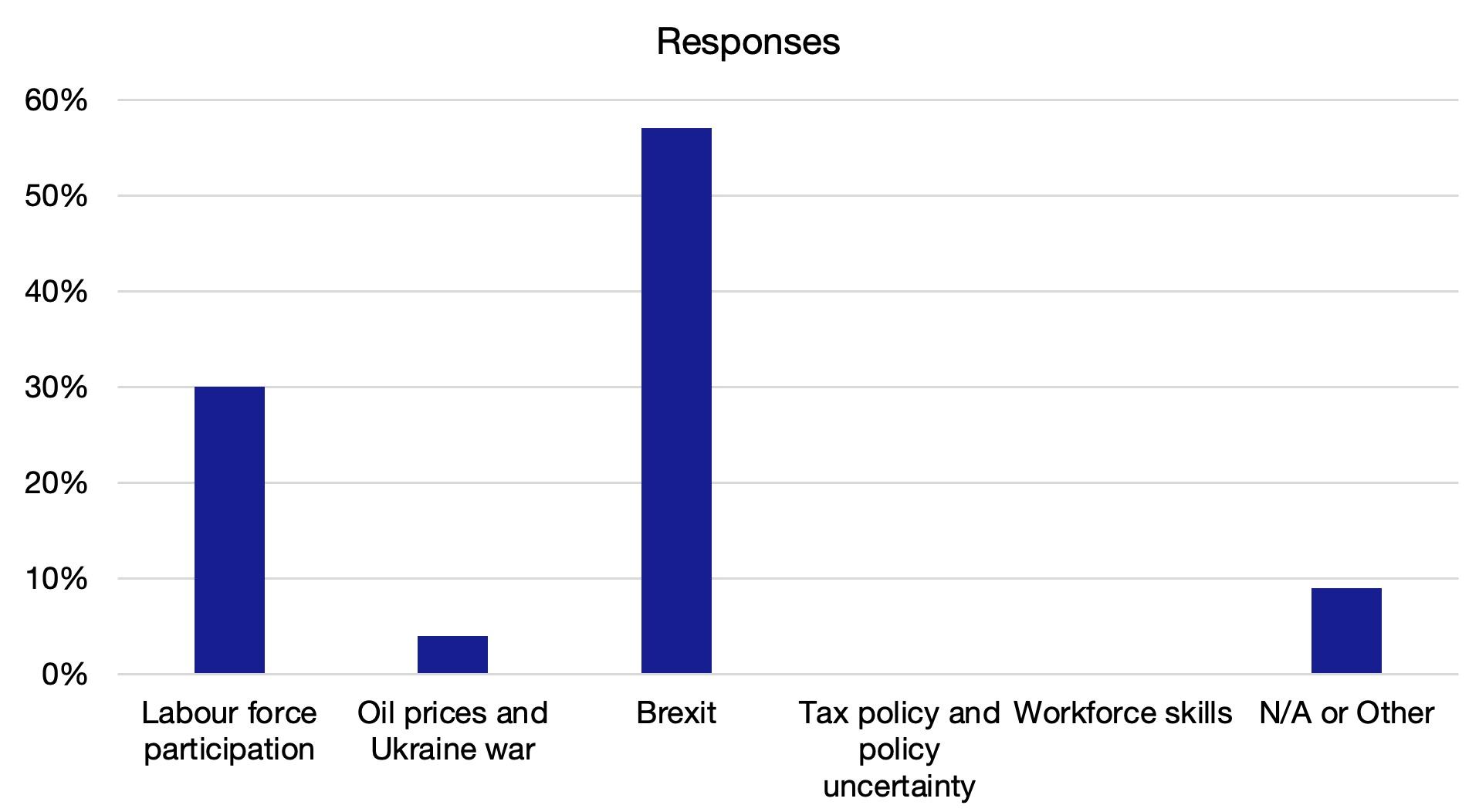

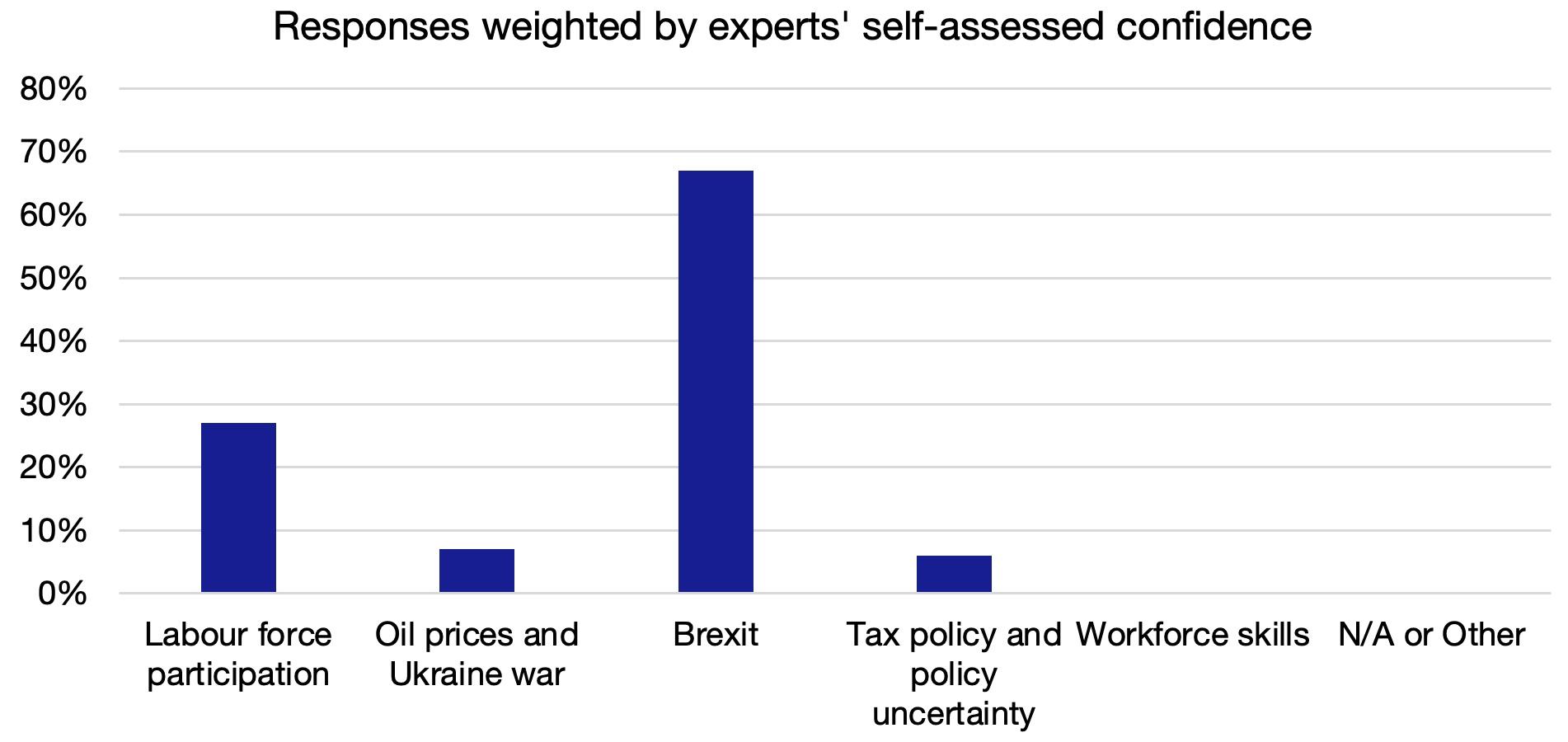

The March 2023 Centre for Macroeconomics–CEPR survey asked the members of its UK panel about the constraints on UK potential output in 2023, relative to its pre-2019 trend. The survey contained two questions. The first asked the panellists to indicate the most important drag on UK potential GDP, in their view. The second asked them for a policy that would do the most to improve UK GDP growth.

Question 1: Which of the following will be the most important constraint on UK potential output in 2023, relative to its pre-2019 trend?

Twenty-two panel members responded to this question. The panel is unified in the view that Brexit will be the most important constraint on UK potential output in 2023 (relative to its pre-2019 trend), with 57% voting for this option. Most of the remainder (30%) think low labour force participation will constrain UK potential output, while only one panellist thinks that oil prices and the Ukraine war will be major economic constraints on UK potential output this year.

More than half of the panel believe that the high economic costs of Brexit – less trade, investment, and migration – will significantly constrain UK potential output in 2023, relative to its pre-2019 trend. John Van Reenen (London School of Economics) highlights the high toll Brexit has exacted on the UK economy because of “the loss of dynamism due to lower trade”. He cites Dhingra et al. (2016), who predicted that Brexit would lower living standards and per-capita income across a range of possible scenarios, and stresses that the constraints imposed by Brexit will significantly hamper the UK’s economic performance. Similar views are expressed by Costas Milas (University of Liverpool), who singles out Brexit as the major factor behind the UK’s low productivity. He states that “firms are (still) unwilling to invest [in the UK] because Brexit is holding us [Britain] back”.

Łukasz Rachel (University College London) offers an alternate mechanism through which Brexit may have impacted the UK economy: political channels. He argues that Brexit has served as a “huge distraction”, diverting state attention from more pressing issues like the skills crisis, and has “kept afloat talentless politicians who lack vision and continuously mismanage the country”.

Some panellists cite poor labour participation as a major constraint on UK potential output in 2023. Martin Ellison (University of Oxford) emphasises the weak productivity of the low-skilled UK workforce, which is reflected in low wages and decisions to leave the labour market. Additionally, he suggests that the UK’s poor-quality workforce has left the country “more exposed to energy prices than it should be”, as workers “lack the skills needed to upgrade the energy-efficiency of its [the UK’s] housing stock”. Moreover, James Smith (Resolution Foundation) emphasises that “it is unlikely that many of the workers leaving the labour market during the pandemic will return”, indicating that the UK’s low labour-force participation problem is here to stay.

An alternate perspective is offered by Jumana Saleheen (Vanguard Asset Management), who cites the Ukraine crisis as the most critical constraint on UK potential output in 2023. She suggests that “if the war in Ukraine were to end, and oil and natural gas prices fell, this would be a positive supply-side shock for the UK economy”, which could boost potential output.

David Cobham (Heriot Watt University) views the issue through yet a different lens, arguing that factors like Brexit are merely a by-product of years of austerity. He claims that the underlying reason behind the UK’s low potential output is the “misguided but longstanding ‘private sector positive, public sector negative’ views which ignore the role of public services in creating the conditions for strong growth”, and urges economists to challenge these views to reverse the UK economic downturn.

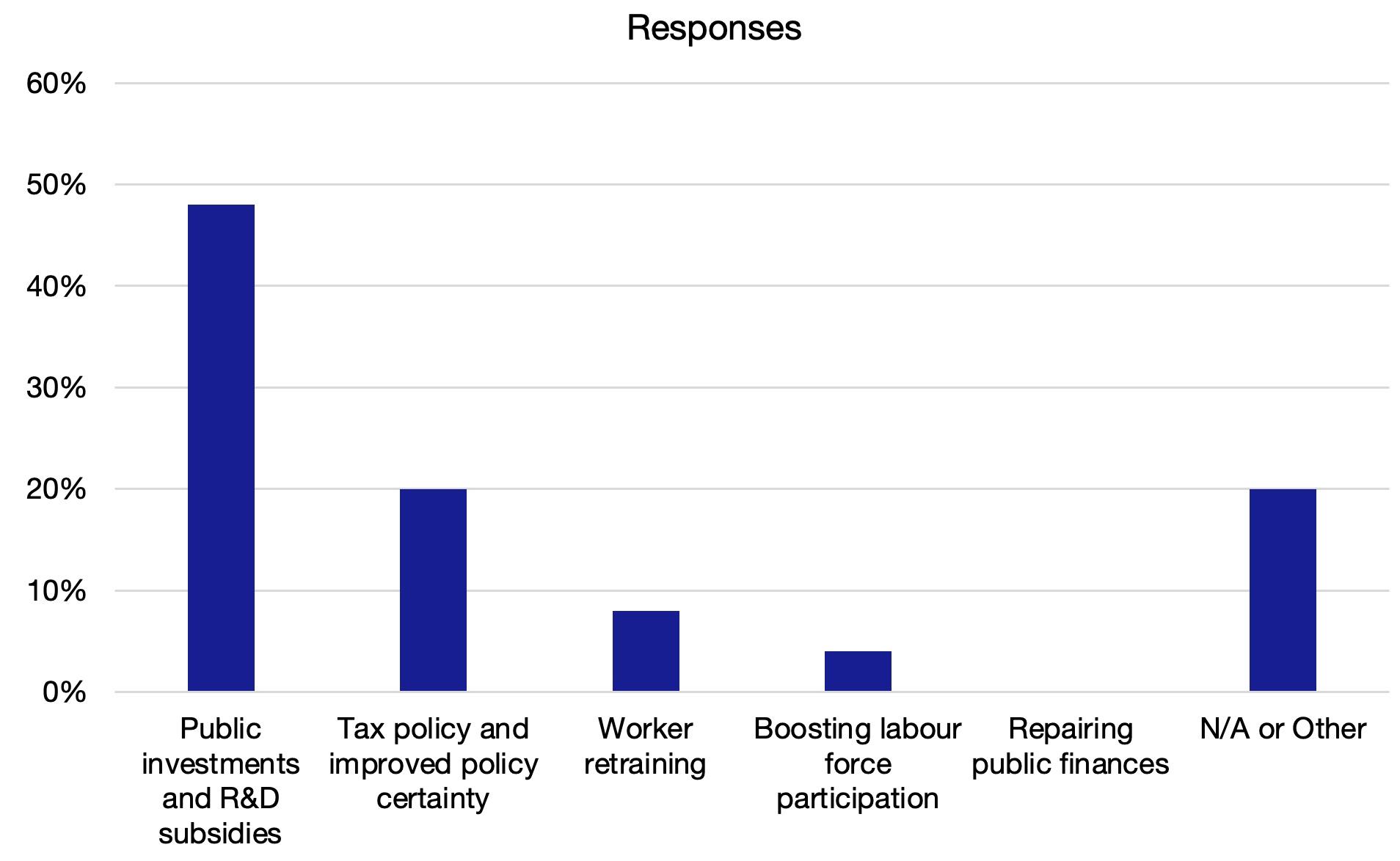

Question 2: Which of the following policies would do the most to boost UK GDP in the medium term (over the next decade)?

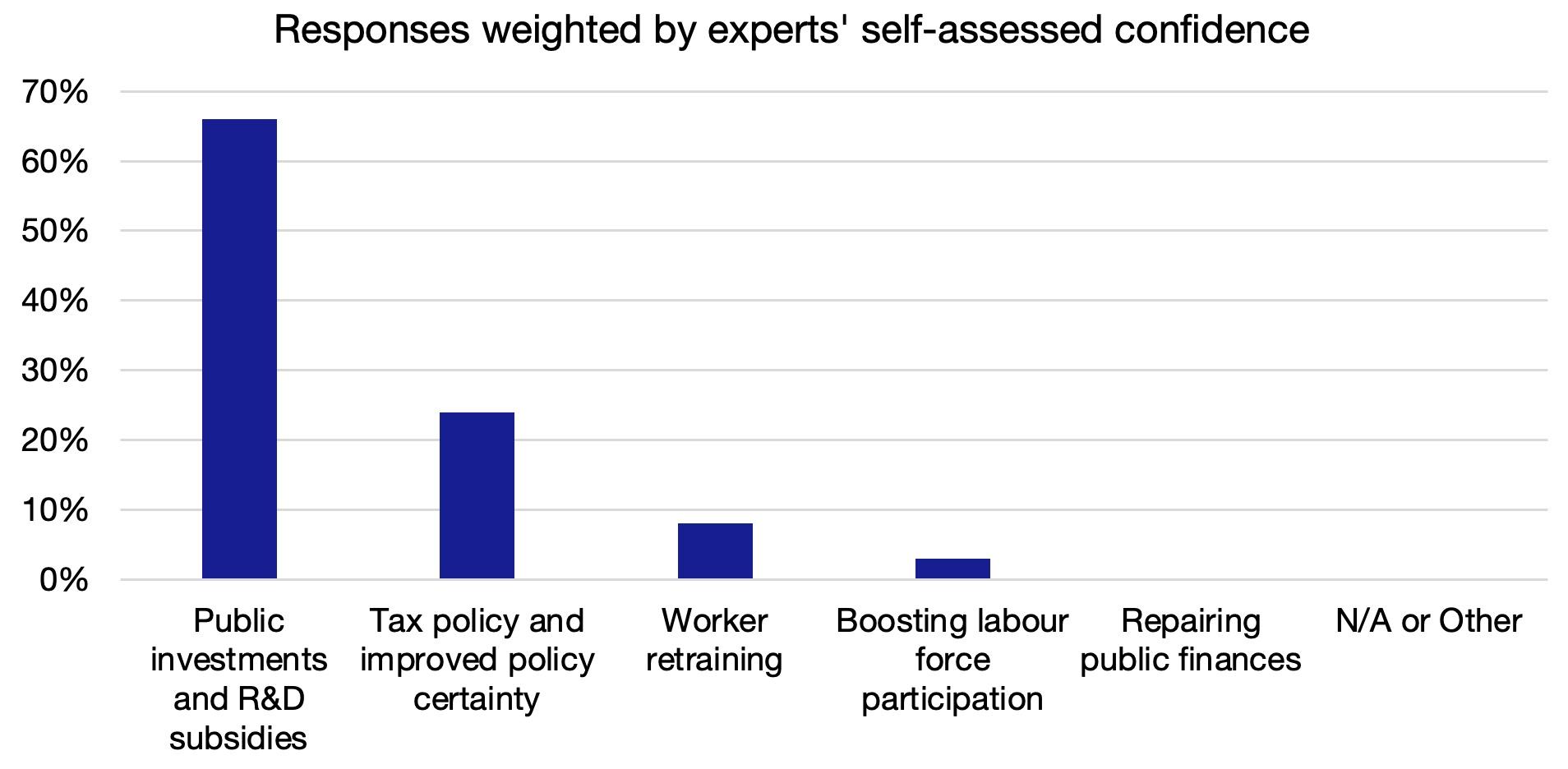

Twenty-four panellists responded to the second question. Around half the panel (48%) favour public investment and R&D subsidies as the remedy for the UK’s low GDP in the medium term. Most of the remaining panel members (20%) believe that tax policy and policy certainty would boost UK GDP over the next decade, while a handful of panellists suggest worker retraining and boosting labour-force participation as potential solutions. However, almost all panellists suggest a combination of policies would be needed to tackle this issue.

Several panellists believe that public investments and R&D subsidies are the most prudent way to boost UK GDP over the next decade. Martin Ellison summarises this view: “Mature economies grow mostly through technological progress. The best returns are therefore likely to be found in policy measures that improve productivity and innovation, so my top two options are public investments and R&D subsidies or worker retraining.”

Andrea Ferrero (University of Oxford) echoes this sentiment, stating: “The infrastructure in the UK is in dire condition and innovation could certainly provide a productivity boost.”

David Cobham further suggests that public investments and R&D would “improve transport and communications, labour skills, labour-force participation and the business environment more generally”, paving the way for ‘higher and more productive business investment’. John Van Reenen substantiates this viewpoint by citing Teichgraeber and Reenen (2022), who provide evidence on the efficacy of different research and innovation policies in boosting productivity growth in various countries.

However, most panellists suggest that a range of policies is needed to resolve this issue and thus indicate that all of the above options could potentially boost UK GDP in the medium term. Ricardo Reis (London School of Economics) sums up this viewpoint: “[It’s] hard to pick one [policy], most of them are needed.”

Morten Ravn (University College London) further elaborates on this, stating “there is a need to invest in skills and infrastructure but short-to-medium-run returns on such investments are probably low to modest”. He suggests that worker retraining is a similar solution – much needed but unlikely to bring about a large short-to-medium-run boost to the economy. He offers a potential solution in the form of boosting labour-force participation but mentions certain obstacles to its efficacy such as low unemployment rates, stagnant real wages, and selection effects in labour market dropouts.

While repairing public finances is unlikely to boost GDP in the short run, he suggests a potential panacea for the UK economy: re-entering the EU single market. Such a move could “boost public finances and the economy”, as per Ravn.

References

Ari, A, N Arregui, S Black, O Celasun, D M Iakova, A Mineshima, V Mylonas, I W H Parry, I Teodoru, and K Zhunussova (2022), Surging energy prices in Europe in the aftermath of the war: How to support the vulnerable and speed up the transition away from fossil fuels, IMF.

Barnes, O, J Pickard, and V Romei (2022), “UK faces ‘cost of doing business’ crisis as energy bills rise fourfold”, FT.com, 25 August.

Coursera (2022), Global skills Report.

Dhingra, S, E Fry, S Hale, and N Jia (2022), The Big Brexit: An assessment of the scale of change to come from Brexit, The Resolution Foundation.

Dhingra, S, G Ottaviano, T Sampson, and J Van Reenen (2016), The consequences of Brexit for UK trade and living standards, Centre for Economic Performance, London School for Economics and Political Science.

Freeman, R, K Manova, T Prayer, and T Sampson (2022), Unravelling deep integration: UK trade in the wake of Brexit, Centre for Economic Performance, London School for Economics and Political Science.

Financial Times (2022), “UK labour shortages are ‘shape of things to come’, lords warn”, FT.com, 19 December.

Gourinchas, P-O (2023), “Global economy to slow further amid signs of resilience and China re-opening”, IMF Blog, 30 January.

Haskel, J, and J Martin (2023), “How has Brexit affected business investment in the UK?”, Economics Observatory, 13 March.

Ilzetzki, E (2020), “Explaining the UK’s productivity slowdown: Views of leading economists”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Institute for Employment Studies (2022), “Labour market statistics, October 2022”, IES Briefing.

Minford, A P, and Z Zhu (2023) “How the short run effects of Brexit on trade, investment and GDP have been miscalculated in some recent work”, mimeo, Cardiff University.

Minford, A P, Yue Gai, and D Meenagh (2022), “North and South: A regional model of the UK”, Open Economies Review 33(3): 565–616.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2022), “Editorial: Confronting the crisis”, OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022, Issue 2, OECD Publishing.

Oulton, N (2019), “The UK and Western productivity puzzle: Does Arthur Lewis hold the key?”, International Productivity Monitor 36: 110–41.

Portes, J (2022), “Trade, migration, and Brexit”, VoxEU.org, 8 September.

Portes, J, and Springford, J (2023), "Early impacts of the post-Brexit immigration system on the UK labour market", CER Insight, Centre for European Reform.

Resolution Foundation and Centre for Economic Performance (2022), Stagnation nation: Navigating a route to a fairer and more prosperous Britain.

Samiri, I, and S Millard (2022), “Why is UK productivity low and how can it improve?”, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, 26 September.

Smith, J, and E Ilzetzki (2022), “Prospects for UK economic growth”, VoxEU.org, 8 June.

Springford, J (2022), What can we know about the cost of Brexit so far?, Policy Brief, Centre for European Reform 9.

Teichgraeber, A, and J V Reenen (2022), “A policy toolkit to increase research and innovation in the European Union”, Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper DP1832.

Waters, T, and T Wernham (2022), Long COVID and the labour market, Institute for Fiscal Studies.