Given the declining labour force due to population ageing, accelerating the productivity growth of industries – especially the service industries – is an important element of the growth strategy in Japan and most advanced countries. While there are a variety of factors affecting productivity, innovation is one of the key determinants of productivity growth. However, innovation in the service sector has not been studied well. I present findings on innovation in the service sector by focusing on the effect of intellectual property rights on innovation.

Mechanisms to foster innovation

It is the well-known nature of innovation that some institutional mechanism is essential to remedy underinvestment in innovative activities. Patents, copyrights, and trade secrets are mechanisms to ensure that innovators appropriate the returns to their innovations. The effective protection of intellectual property is therefore an important policy to promote innovations and productivity growth. The ‘Japan Revitalization Strategy’ – the new growth strategy of the Shinzo Abe Cabinet revised in June 2014 – states that the government endeavours to make Japan “the world’s most excellent intellectual property-based nation.”

Since an influential work by Levin et al. (1987), a number of studies have analysed firms’ choice of appropriation mechanisms for their innovations. These studies generally find that appropriation mechanisms other than patent filing – such as secrecy and lead time – play important roles for firms in advanced countries (see Hall et al. 2014 for a survey). However, the subjects of most studies are confined only to manufacturing firms, and the difference between manufacturing and service firms has not yet been sufficiently explored.

In order to shed light on innovation in the service sector, I conducted an original survey of Japanese firms and investigated the role of intellectual property rights by linking the survey data with micro data from official statistics. There are 3,444 firms in the sample, of which manufacturing and service firms comprise 1,567 and 1,860, respectively (the details of the data and the results are presented in Morikawa 2014).

Innovation and productivity in the service sector

Generally speaking, formal research and development (R&D) investments are more prominent among manufacturing firms compared with firms in the service industry. According to the Basic Survey of Japanese Business Structure and Activities (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), in 2011, the mean R&D intensity of service firms was about one-third of the figure for manufacturing firms. However, innovation is not necessarily developed by formal R&D investments. Recent productivity studies stress focusing more on ‘soft innovations’ related to human resources, organisational change, and other intangible investments in analysing innovations in the service sector (e.g. Jorgenson and Timmer 2011).

According to our survey, the percentages of firms that developed new products/services during the past three years are 48.6% and 36.5% for manufacturing and service firms, respectively. While the figure is higher among the manufacturing firms, a relatively large number of service firms have produced new innovative services.

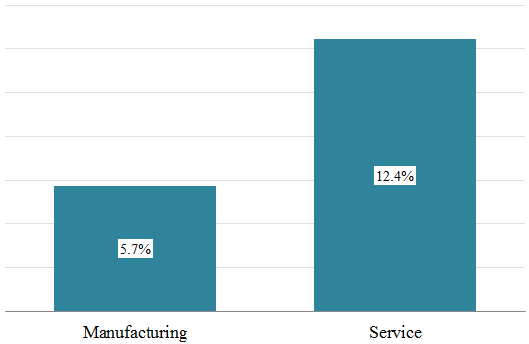

I compare the mean total factor productivity (TFP) levels of firms with and without products/services innovation. It is obvious that products/services innovation has a positive relationship with TFP in both the manufacturing and service firms. Interestingly, however, the difference in TFP with or without innovation is larger among the service firms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Products/services innovations and TFP

Note: The bars indicate the differences in mean TFP levels between firms with and without innovations.

The role of patents and trade secrets

In Japan, trade secrets are protected by the Unfair Competition Prevention Act. Trade secrets protected by the law are not limited to technological information such as manufacturing know-how. Non-technological information such as customer lists, food recipes of restaurants, sales or service manuals, and contract information can be protected as trade secrets. These types of non-technological information are often possessed by firms in the service sector.

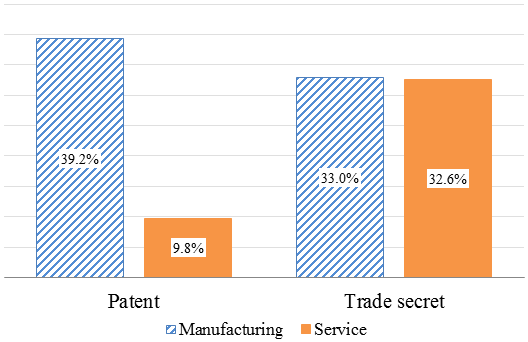

Figure 2 shows the percentages of firms holding patents and trade secrets. The percentages of firms holding patents are 39.2% for manufacturing firms and 9.8% for service firms – a large and statistically significant difference. On the other hand, the percentages of firms holding trade secrets are 33.0% and 32.6% for manufacturing firms and service firms, respectively – the difference between industries is statistically insignificant. These patterns suggest that trade secrets are relatively important appropriation measures of intellectual property in the service sector.

Figure 2. Percentages of firms holding patents and trade secrets

I conducted a simple probit estimation with the existence of new innovations as the dependent variable, and the holding of patents and trade secrets as the key explanatory variables. After controlling for firm characteristics, the estimated coefficients for patents and trade secrets are positive and significant for both the manufacturing and service firms.

Although the size of the coefficient is larger for patents than for trade secrets, the number of firms holding patents is very small among service firms (as seen in Figure 2). That is, in comparison with the manufacturing industry, trade secrets are a relatively important appropriation mechanism in the service industry.

The findings that the innovative service firms exhibit high productivity and that the holding of intellectual properties is strongly related to innovations in the service industry suggest that the law protecting trade secrets is an important contributor to productivity growth in the service industry. Whether the current legal system regarding intellectual property is sufficient for promoting soft innovations in the service industry is a high priority area for further research.

Editor’s note: The main research on which this column is based (Morikawa 2014) first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Hall, Bronwyn H, Christian Helmers, Mark Rogers, and Vania Sena (2014), “The Choice between Formal and Informal Intellectual Property: A Review”, Journal of Economic Literature, 52(2): 375–423.

Jorgenson, Dale W and Marcel P Timmer (2011), “Structural Change in Advanced Nations: A New Set of Stylised Facts”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(1): 1–29.

Levin, Richard C, Alvin K Klevorick, Richard R Nelson, and Sidney G Winter (1987), “Appropriating the Returns from Industrial Research and Development”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 3 (Special Issue on Microeconomics): 783–820.

Morikawa, Masayuki (2014), “Innovation in the Service Sector and the Role of Patents and Trade Secrets”, RIETI Discussion Paper 14-E-030.