The creation of the euro in 1999 was expected to become a catalyst for real convergence in Europe. Instead, real divergence increased as evidenced by low productivity growth in the ‘periphery’ of the euro area relative to ‘core’ countries. This divergence was accompanied by massive capital flows from the euro area’s core – Germany, the Netherlands – to its periphery, (e.g. Portugal or Spain). The process left peripheral economies with financial and real estate bubbles – Spain being emblematic of the latter – together with a continuously weakening manufacturing sector while this same sector gained strength in Germany (Krugman 2013).

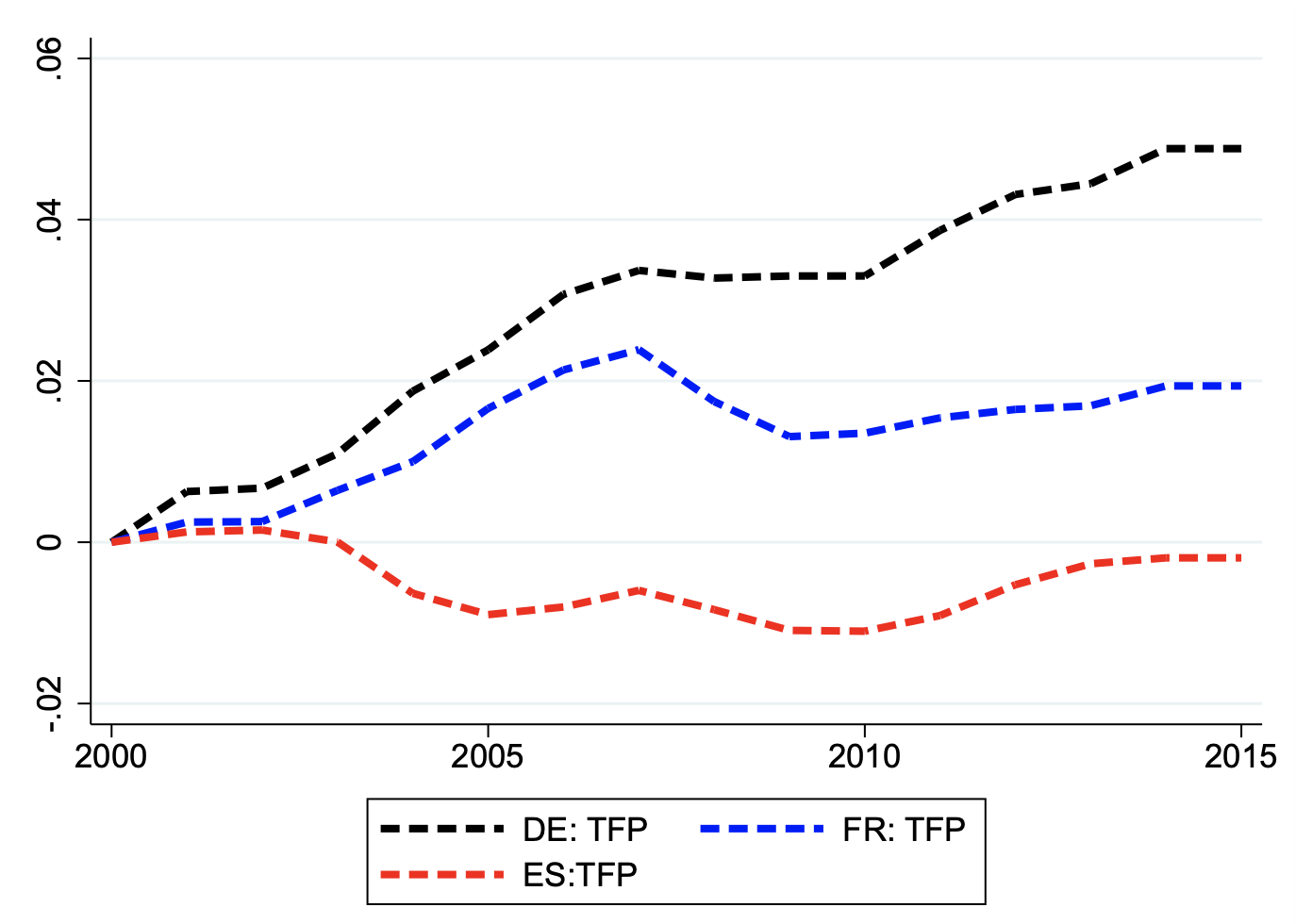

Figure 1 provides a striking illustration of the divergence process at work in the euro area since the beginning of the 21stcentury. It focuses on three countries emblematic of structural divergences within the euro area: Germany and Spain, for the previously mentioned reasons, as well as France, which is often described as occupying an ‘in-between’ position. Between 2000 and 2015, Spanish total factor productivity (TFP) stagnated, while French TFP increased at half the pace of German TFP.

Figure 1 TFP dynamics

Note: This figure uses EU KLEMS data and measures TFP as a weighted average of sectoral TFP based on a classification with 33 sectors. Country-level TFP (in log, with value set to 0 in 2000) built using historical value-added shares by sector as weights. DE: Germany, ES: Spain, FR: France

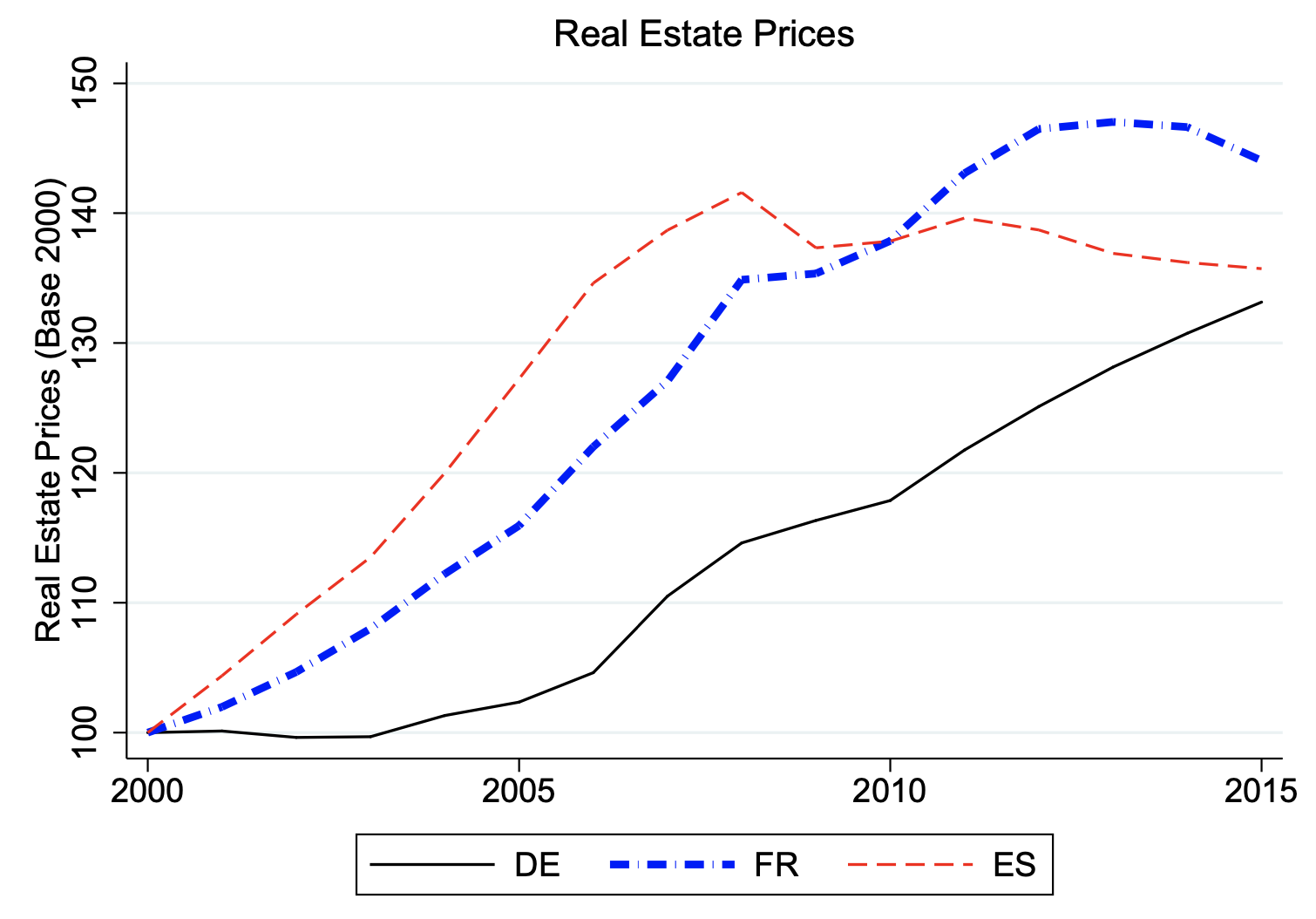

Parallel to this real divergence, European countries experienced heterogeneous real estate price dynamics which took the form, in some economies, of massive boom-bust cycles. These real estate booms occurred notably in Spain and France, while price increases were more moderate in Germany, particularly in the first decade of the sample (Figure 2). This column argues that real estate prices contributed to both the productivity divergence and the slowdown in the EU through a sectoral reallocation mechanism.

Figure 2 Real estate prices

Note: Country-level real estate prices (index, with value set to 100 in 2000). DE: Germany, ES: Spain, FR: France.

The key role of sectoral reallocations in productivity dynamics

A recent literature studies the role of resource misallocations in explaining international differences in productivity by focusing on within-sector reallocations among firms (see e.g. Bartelsman et al. 2013, Banerjee and Coricelli 2017, García-Santana et al. 2020). However, in recent research (Grjebine et al. 2022), we show that reallocation between sectors is a strong candidate in explaining both the productivity slowdown observed in most EU countries and the divergence between them.

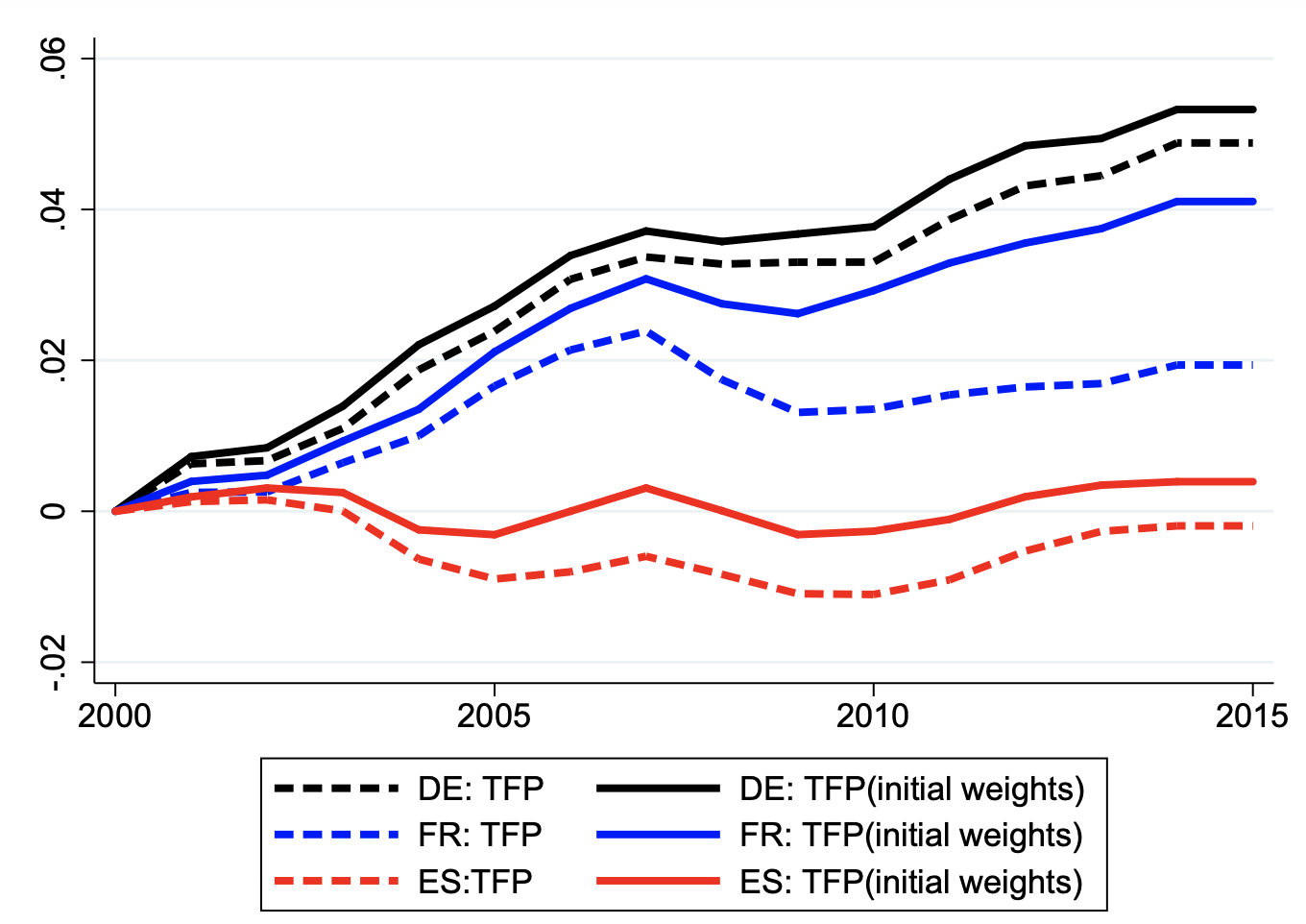

Based on a database of 33 sectors and 14 countries between 1995 and 2015, Figure 3 compares the actually observed TFP to a counterfactual aggregate TFP, based on a weighted sum of sectoral TFP for which the share in value-added for each sector has been set to its 2000 level. In Spain, the TFP dynamics would not have been negative without these reallocations. In France, the difference between the cumulative growth of TFP for the initial sectoral structure and the observed growth of TFP is around 2%. This disparity means that without sectoral reallocations, growth in TFP could have doubled. The gap in cumulative TFP growth between France and Germany would also have been reduced from about 1.5 percentage points to 0.5 points. The right panel shows the difference between the plain and the dashed lines for each of the three considered countries, revealing the extent of the divergences in TFP dynamics fuelled by sectoral reallocations: whereas losses have been limited in Germany, they have been significant in Spain (until a reversal in 2008) and continued increasing in France. We report TFP losses due to sectoral reallocations for the 14 studied European countries. TFP losses due to sectoral reallocations are largest in France, followed closely by Denmark, Finland, and Portugal. Losses are also substantial in the UK, Italy, and Austria.

Figure 3 TFP losses due to sectoral reallocations

(a) TFP vs. TFP without sectoral reallocations

(b) TFP losses due to sectoral reallocations

Note: Panel (a): ‘TFP’ is the country-level TFP (in log, with value set to 0 in 2000) built using historical value-added shares by sector as weights. ‘TFP (initial weights)’ is the country-level TFP using initial value-added shares by sector as weights. Panel (b): ‘TFP losses’ displays the gap between ‘TFP’ and ‘TFP (initial weights)’. DE: Germany, ES: Spain, FR: France.

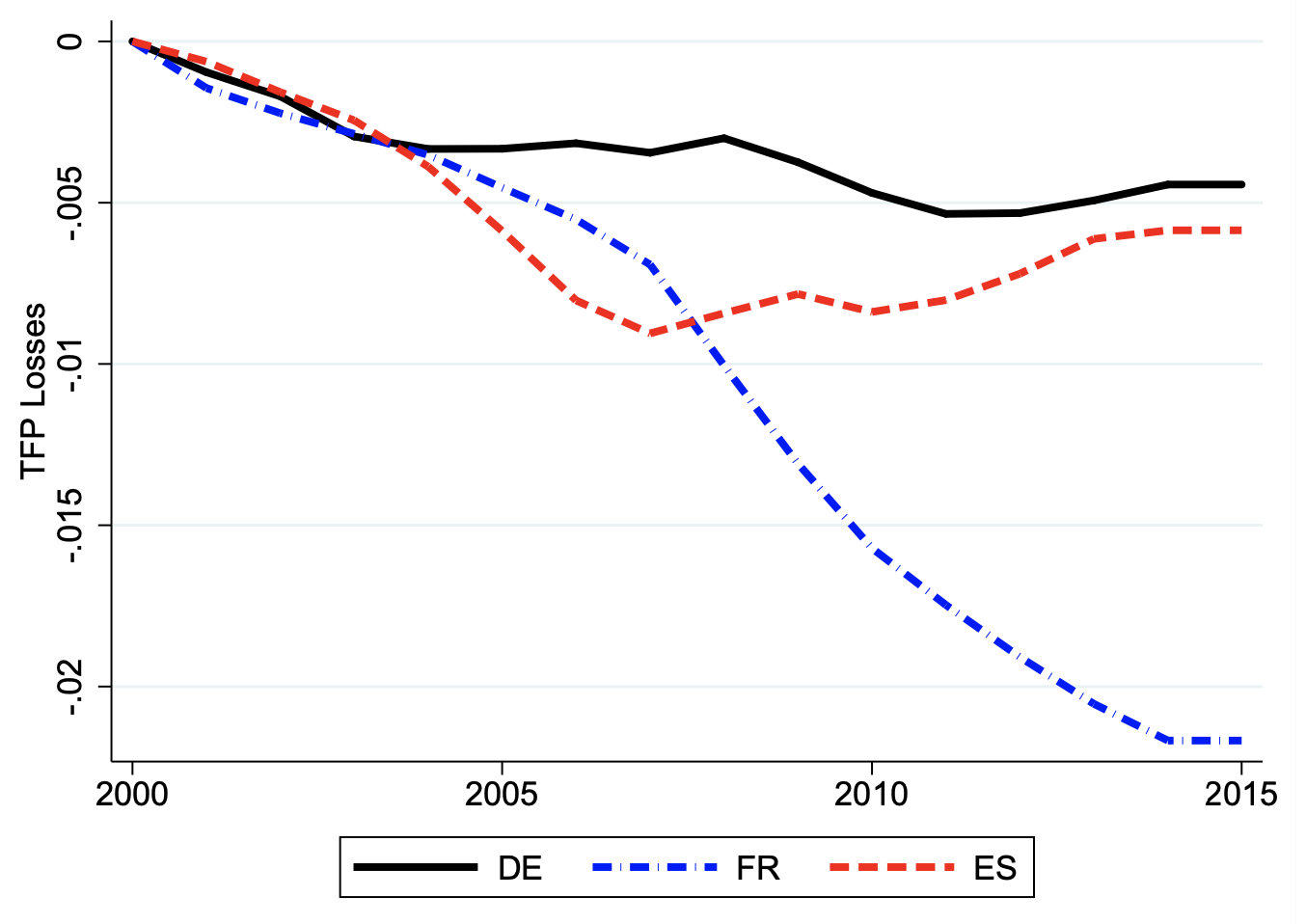

Figure 4 compares the dynamics of real estate prices with those of TFP. It is striking to see that the dynamics of TFP losses and real estate prices reflect each other closely, and that periods of booming real estate prices generally coincide with sectoral reallocations detrimental to TFP. This clearly suggests a relationship between the two phenomena.

Figure 4 Real estate prices versus TFP losses

Note: Country-level real estate prices (index, with value set to 100 in 2000). ‘TFP losses’ displays the gap between ‘TFP’ and ‘TFP (initial weights)’. ‘TFP’ is the country-level TFP (in log, with value set to 0 in 2000) built using historical value-added shares by sector as weights. ‘TFP (initial weights)’ is the country-level TFP using initial value-added shares by sector as weights.

Real estate shocks as a trigger for sectoral reallocations

In this regard, real estate shocks lead to reallocations involving all sectors of the economy, and not only towards construction, thus transforming the structure of the economy. More specifically, we use variations in (real estate) collateral at the country-sector level to identify the impact of real estate shocks on sectoral reallocations. The collateral mechanism is linked to the ‘financial accelerator’ (Bernanke and Gertler 1989, Kiyotaki and Moore 1997): with imperfect financial markets, financially constrained sectors (and firms within these sectors) will use their pledgeable assets as collateral to finance their investment (Chaney et al. 2012). Consistently, we expect that an increase in the value of the collateral will allow sectors to increase their investment, the more so if the sector has relatively more collateral (which we measure through the amount of real estate capital owned by the sector).

More specifically, we identify exogenous shocks to domestic real estate prices through a combination of world demand shocks and country-level supply constraints on the real estate market. This allows us to recover the causal impact of real estate price shocks on investment, share of total value added (as a proxy for sectoral size), and TFP growth at the country-sector level. Our results show that exogenous real estate price shocks increase sectoral investment and size: a 10-percentage point increase of real estate sectoral holdings brings an additional 0.8 percentage points in the ratio of investment to capital stock, and an additional 6 percentage points to the ratio of gross value added to capital stock. Conversely, we find no significant impact on sectoral TFP. Put differently, real estate shocks may affect aggregate TFP exclusively through a sectoral reallocation mechanism.

Interestingly, we find that these productivity effects of real estate price shocks are not only quantitatively non-negligible but also point to a greater divergence between EU countries. On the one hand, there is a group of countries where real estate shocks generate TFP losses, including countries where real estate booms started early and were substantial, such as Ireland, the UK, France, and Spain. On the other hand, there is another group of countries for which our mechanism generates TFP gains – including Germany, Austria, and Italy, where real estate prices grew later or at a slower pace. These results fit well with recent work by Hau and Ouyang (2018), whose data for the Chinese manufacturing sector demonstrate that real estate booms exert a detrimental effect on other industries through the diversion of local savings into the real estate sector.

Policy implications

The lack of real convergence between countries is a major obstacle to the proper functioning of the euro area. This column highlights the importance of a sectoral specialisation mechanism triggered by real estate cycles in feeding this lack of real convergence. This explains Spain’s lag behind Germany before the Great Recession, and partly explains France’s lag afterwards. In this regard, real estate shocks not only lead to reallocations towards the construction sector, but also change the relative size of every sector and consequently the whole structure of economies.

In this work, we remain relatively agnostic about fundamental shocks that drive real estate prices. Diverging financial or housing cycles – in particular between France and Spain on the one hand and Germany on the other – could be due to diverging demand shocks at the national level such as diverging fiscal policies. From a policy perspective, institutions that want to promote the convergence of productivity in Europe should thus not only focus on supply-side policies but should also take into account the effects of diverging national demand shocks on the European productivity divergence.

References

Banerjee, B and F Coricelli (2017), “Misallocation in Europe during the global financial crisis: Some stylised facts”, VoxEU.org, 8 February.

Bartelsman, E, J Haltiwanger and S Scarpetta (2013), “Cross-country differences in productivity: The role of allocation and selection”, American Economic Review 103(1): 305–34.

Bernanke, B and M Gertler (1989), “Agency Costs, Net Worth, and Business Fluctuations”, American Economic Review 79(1): 14–31.

Chaney, T, D Sraer and D Thesmar (2012), “The collateral channel: How real estate shocks affect corporate investment”, American Economic Review 102(6): 2381–2409.

García-Santana, M, E Moral-Benito, J Pijoan-Mas and R Ramos (2020), “Growing like Spain: 1995–2007”, International Economic Review 61(1): 383–416.

Grjebine, T, J Héricourt and F Tripier (2022), “Sectoral Reallocations, Real-Estate Shocks, and Productivity Divergence in Europe”, Review of World Economics, forthcoming.

Hau, H and D Ouyang (2018), “Local capital scarcity and industrial decline caused by China’s real estate booms”, VoxEU.org, 26 October.

Kiyotaki, N and J Moore (1997), “Credit Cycles”, Journal of Political Economy 105(2): 211–248.

Krugman, P (2013), “Revenge of the optimum currency area”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 27(1): 439–448.