Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 and subsequent sanctions against Russia, global economic prospects have worsened significantly and energy and food prices have increased sharply worldwide (IMF 2022). In Germany, inflation as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) rose quickly to 7.6% in March and increased to even higher levels in the following months, to a magnitude last seen in the 1950s in Germany. Besides energy, non-energy raw materials from Ukraine and Russia such as wheat and corn, as well as intermediate goods such as fertiliser, also play a major role for the German food sector. Consumers have not only adjusted their inflation expectations upwards (Afunts et al. 2022), but they are also facing increased uncertainty (Anayi et al. 2022), possibly giving rise to stockpiling behaviour.

The current episode shows that inflationary waves can unfold extremely quickly, making reliable real-time information about inflation dynamics of utmost importance for central bankers and other policymakers. However, official inflation statistics are available only at a monthly frequency and with a certain time lag. For example, the headline flash estimate of the German HICP is published at the end of the reporting month, while final figures for more disaggregate products are released only in the middle of the subsequent month. Starting with Cavallo and Rigobon (2016), the literature has increasingly pointed out the usefulness of high-frequency price indicators based on ‘webscraping’ or scanner data to provide a more timely inflation measure almost in real time.

In this column, we use weekly retail scanner data from the GfK household panel to analyse both prices and quantities of food products in Germany in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This dataset has the advantage that a detailed breakdown of the inflation rate is already available two days after the end of each week which is almost six weeks before the publication of the official HICP components. In addition, the dataset contains transactions including the volume of sales per products. Both pieces of information are very valuable in times of crisis that are often marked by significant changes in consumption patterns. This has been shown by Cavallo (2020) for the Covid-19 period, whereas Cavallo and Kryvtsov (2022) suggest that product shortages can have non-negligible inflationary effects in the short run. In our corresponding paper (Beck et al. 2022), we also document good nowcasting properties of our high-frequency disaggregate data, similar to other studies (Modugno 2013, Harchaoui and Janssen 2018, Aparicio and Bertolotto 2020, Joseph et al. 2021), although a detailed exposition of these results goes beyond the scope of this column.1

Heterogeneous sales and price effects following Russia’s invasion

We analyse the developments in prices and quantities in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for six staple food products (sunflower oil, flour, butter, low fat milk, bread, and coffee pods). Although these products make up only 1.7% of the German headline inflation, they are an important driver of consumers’ frequent out-of-pocket purchases that again strongly affect consumers’ inflation expectations. Moreover, increasing prices of sunflower oil and flour have been discussed quite prominently in the context of supply chain disruptions and trade embargoes. Since Ukraine accounts for 75% of globally traded sunflower oil (McGuirk and Burke 2022) and, combined with Russia, both supply over a quarter of global wheat exports, the conflict has severely disrupted the supply of these staples while increasing export restrictions have magnified the surge in food prices (Espitia et al. 2022, Artuc et al. 2022). Our weekly price and quantity indicators cover the period of January 2019 until the first week of June 2022 (179 weeks in total).

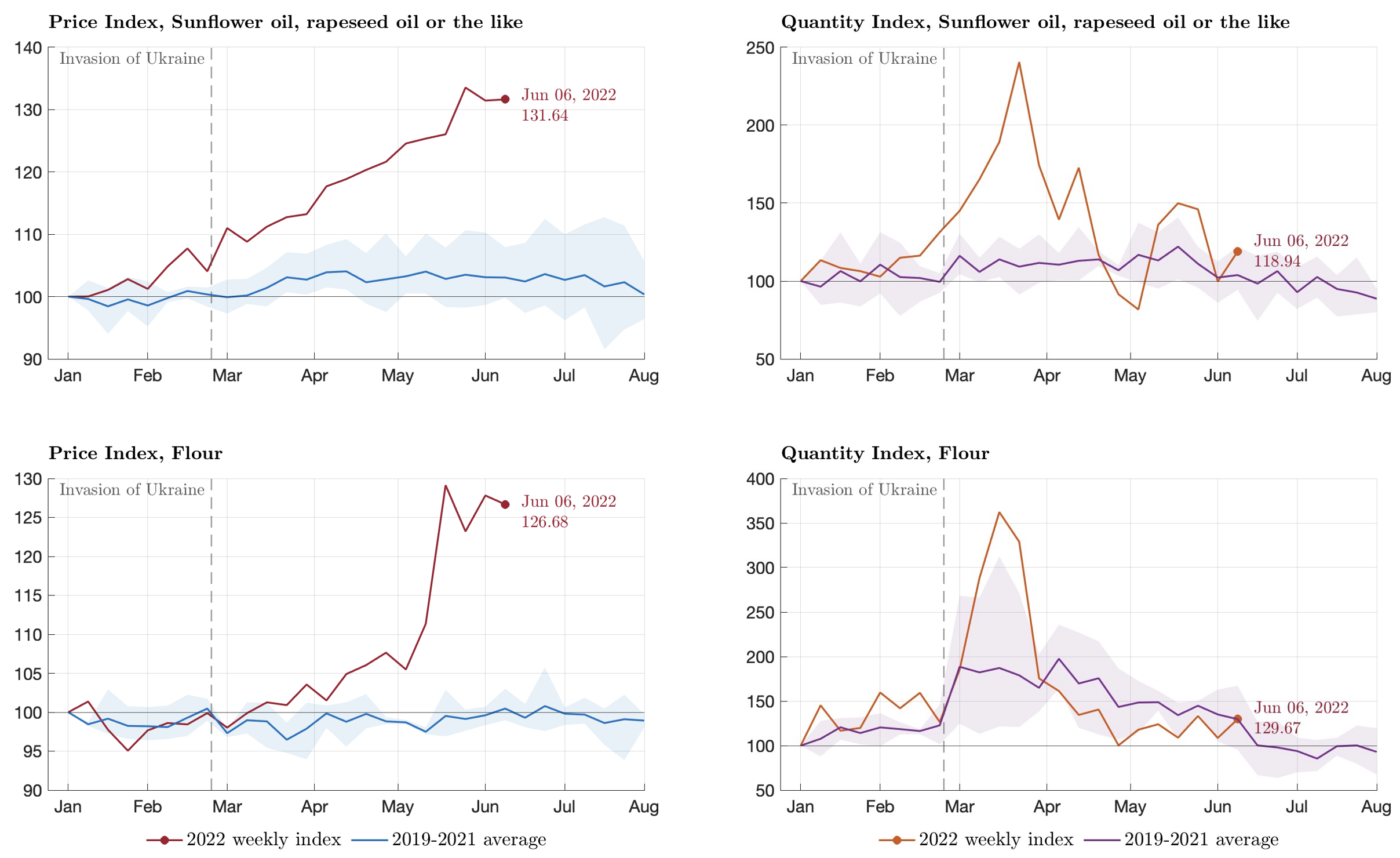

Our scanner-based indices signal a very strong increase in prices for sunflower oil and flour in light of the conflict, accompanied by temporarily higher sales. Figure 1 plots the weekly price and quantity indices for each of the mentioned food products. It compares trajectories in 2022 (red and orange solid lines) with their historical average from 2019 to 2021 (blue and purple solid lines) along with historic minimum and maximum values (shaded areas). According to this, the price increase of sunflower oil was rather gradual and already started as of early February. In contrast, prices for flour increased very sharply, but only more than two months after the start of the invasion. In both cases, however, sales went far beyond their average levels signalling increased demand and possibly stockpiling behaviour.2 The increase in sales for flour even surpassed the very high levels observed during the first Covid-19 lockdown in March 2020, as reflected by the upper range of the shaded area. Concerning the more recent period up to June 2022, prices for both products seemed to have stabilised at a very high level, whereas quantities have converted back to their average level.

Figure 1 Rising prices and rising quantities

Sources: GfK household panel, own calculations.

Note: The figure shows weekly developments of price (left panel) and quantity (right panel) indices (Jevons fixed-base, 1st week of January=100) based on GfK household scanner data for selected food products in Germany.

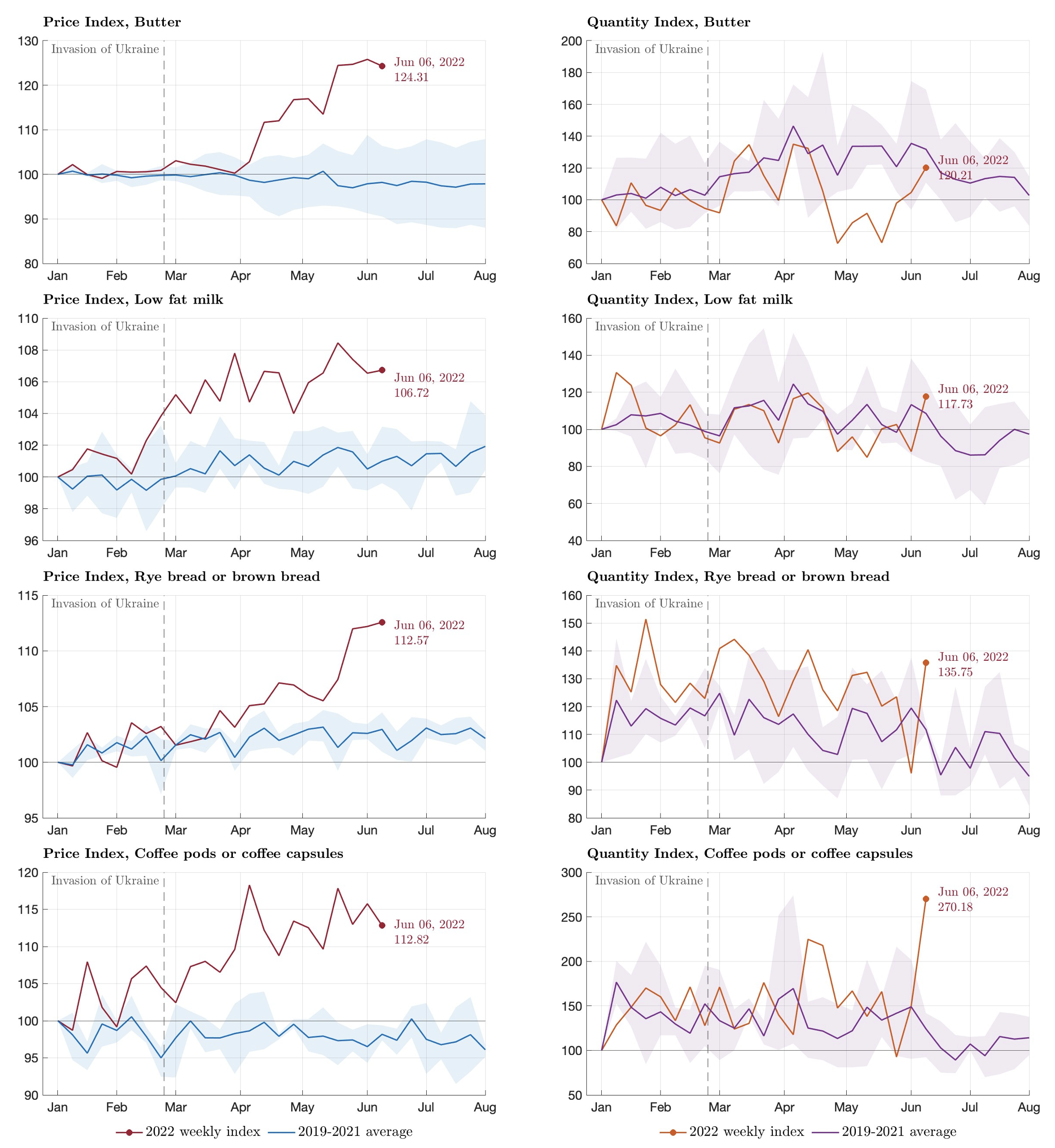

In contrast, other staple products such as milk, bread, and coffee exhibited above-average price increases while their sales remained rather unaffected. As of early June, prices for low fat milk have been increasing by 3%, for coffee pods by 8%, and for rye bread by 9% since the Russian invasion (see Figure 2). The corresponding quantity indices do not signal strong above-average increases. Butter is slightly different since quantities also did not exceed average levels but actually dropped below their previous minimum at the end of April, possibly as a response to a sudden spike in its prices. The latest figures for June signal that prices have stabilised at a very high level. Sales also went back to their historical average for milk and butter, but recently peaked again for coffee and bread.

Figure 2 Rising prices and stable quantities

Sources: GfK household panel, own calculations.

Note: The figure shows weekly developments of price (left panel) and quantity (right panel) indices (Jevons fixed-base, 1st week of January=100) based on GfK household scanner data for selected food products in Germany.

Conclusion

In this column, we have illustrated the behaviour of prices and sales of selected food categories in Germany in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, showing that price increases have been broad-based while the reaction in sales has been very heterogeneous. We believe that highlighting and understanding price dynamics of very specific goods is important since consumers often base their inflation expectations on daily shopping experiences. In our corresponding paper (Beck et al. 2022), we also show that high-frequency scanner data carry real-time predictive information that can be exploited to nowcast official inflation figures. Such timely information on a granular level also enables decision makers to get first and very strong indication of soaring consumer prices in real time.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are the authors’ personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem.

References

Afunts, G, M Cato, S Helmschrott and T Schmidt (2022), “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to higher inflation expectations of individuals in Germany”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

Anayi, L, N Bloom, P Bunn, P Mizen, G Thwaites and I Yotzov (2022), “The Impact of the War in Ukraine on Economic Uncertainty”, VoxEU.org, 16 April.

Aparicio, D and M I Bertolotto (2020), “Forecasting Inflation with Online Prices”, International Journal of Forecasting 36(2):232–247.

Artuc, E, G Falcone, G Porto and B Rijkers (2022), “War-induced food price inflation imperils the poor”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Beck, G, K Carstensen, J-O Menz, R Schnorrenberger and E Wieland (2022), “Using high- frequency scanner data to evaluate German food prices in real time”, Working Paper.

Cavallo, A (2020), “Inflation with COVID Consumption Baskets”, NBER Working Paper 27352:1–18.

Cavallo, A and O Kryvtsov (2022), “What Can Stockouts Tell Us About Inflation? Evidence From Online Micro Data”, NBER Working Paper 29209:1–39.

Cavallo, A and R Rigobon (2016), “The Billion Prices Project: Using Online Prices for Measurement and Research”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(2):151–178.

Destatis (2022), “Ad hoc Evaluation of Experimental Data Shows Stockpiling Purchases of Edible Oil and Flour”, Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis).

Espitia, A, S Evenett, N Rocha and M Ruta (2022), “Widespread food insecurity is not in- evitable: Avoid escalating food export curbs”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Harchaoui, T and R Janssen (2018), “How can Big Data Enhance the Timeliness of Official Statistics?: The Case of the U.S. Consumer Price Index”, International Journal of Forecasting 34(2):225–234.

International Monetary Fund (2022), World Economic Outlook. War Sets Back the Global Recovery, Washington, DC.

Joseph, A, G Potjagailo, E Kalamara and G Kapetanios (2021), “Forecasting UK Inflation Bottom Up”, mimeo.

McGuirk, E and M Burke (2022), “War in Ukraine, world food prices, and conflict in Africa”, VoxEU.org, 26 May.

Modugno, M (2013), “Now-casting Inflation Using High Frequency Data”, International Journal of Forecasting 29(4):664–675.

Endnotes

1 Our results are part of the much broader research project “Nowcasting Consumer Price Inflation in Germany with Retailer and Household Scanner Data” that seeks to analyse retailer and household scanner data in Germany and that comprises fast-moving as well as slow-moving consumption goods. Details can be found at http://www.miggroprices.eu/index.php/research.

2 This is also in line with Destatis (2022) who find that sales for edible oil more than doubled, and flour sales more than tripled in comparison to the pre-war period. They use experimental scanner data from several retailers starting in September 2021.