Better access to high-quality microeconomic data has recently revived interest in measuring economic inequality, also in the context of redistributive effects of monetary policy (e.g. Coibion et al. 2017 for the US or Slacalek et al. 2020 for the euro area, as well as the discussion in Ilzetzki 2021 and references therein). Macroeconomic modelling quickly followed suit, especially in form of heterogeneous agent New Keynesian (HANK) models that incorporate uninsurable idiosyncratic risk as a key source of household heterogeneity (Kaplan et al. 2018). This class of models stresses the role of indirect effects of monetary policy arising from general equilibrium forces, which lead to an expansion in economic activity and lower unemployment. This line of research typically implies that monetary easing benefits not only wealthy agents who gain from asset price appreciation, but also poorer households relying mainly on labour income.

HANK models, however, usually abstract from life-cycle considerations. This contrasts with the importance of the age dimension of household heterogeneity, which is well documented in the empirical literature (e.g. Kuhn and Rios-Rull 2016) and its inclusion in macroeconomic models is crucial to match the wealth Gini coefficient found in the data (De Nardi 2015).

In our recent paper (Bielecki et al. 2021) we look at the role of life-cycle motives in shaping the redistributive effects of monetary policy. We develop a structural model where agents differ along the age dimension in labour productivity, net worth, and composition of asset portfolios. We calibrate the model such that the implied age profiles closely match the euro area data from the Household Finance and Consumption Survey. Our model also includes a realistic representation of general equilibrium forces that are key for indirect effects. Our main message is that life-cycle aspects are very important to appropriately account for redistributive effects of monetary policy and omitting them can lead to wrong conclusions.

Static accounting approach

A common approach to estimating redistribution due to monetary policy boils down to first assessing the asset price appreciation and inflation that can be attributed to monetary policy, and then, for each type of household, calculating the associated change in income or net worth. In line with the HANK literature, some studies additionally include the effects of changes in labour income, typically over a short horizon (e.g. Andersen et al. 2020, Amberg et al. 2021).

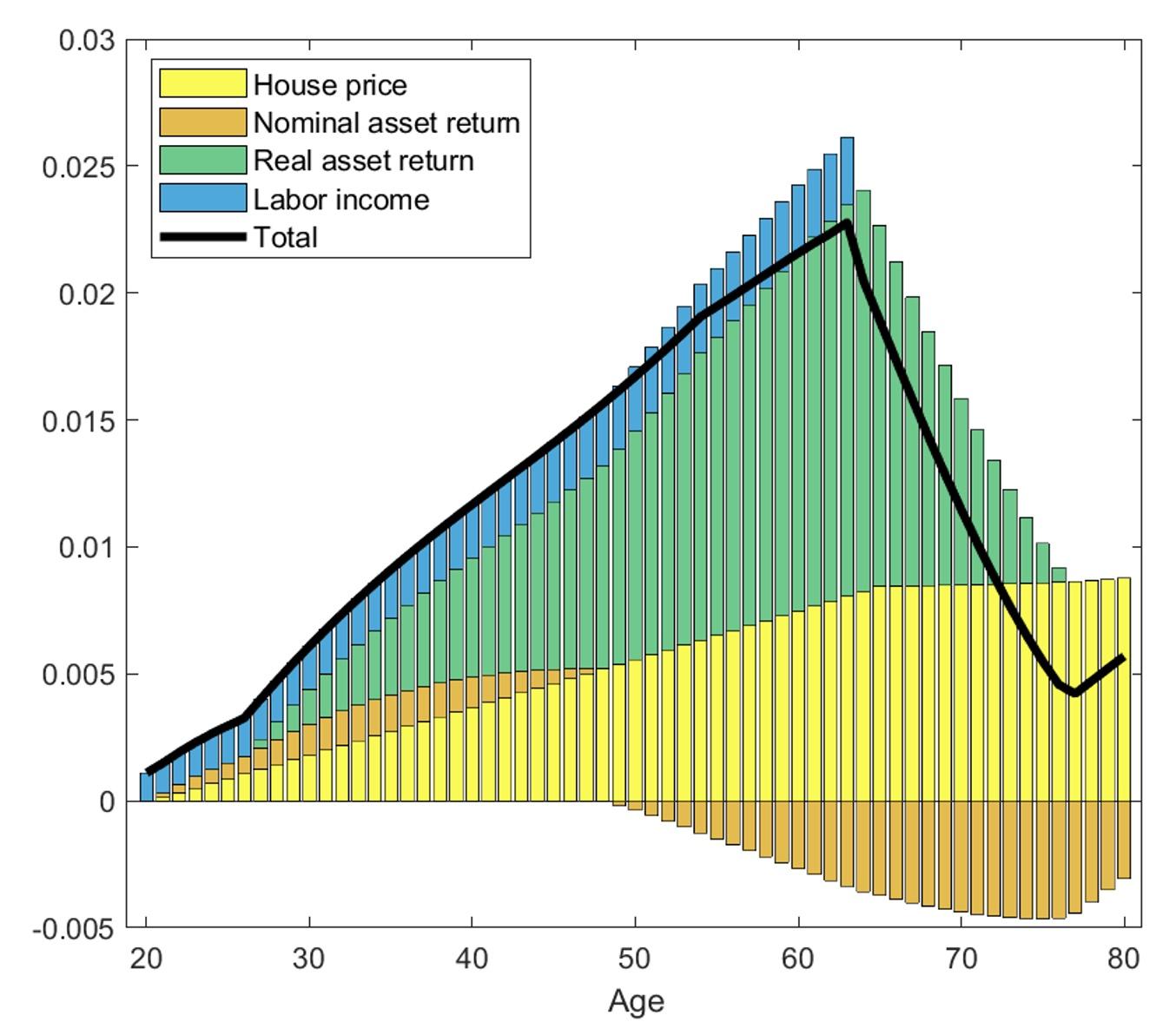

Figure 1 shows the outcomes of such a short-term accounting exercise. As each cohort holds some housing on average, the gains attributed to house price appreciation are all positive. Agents also face a redistribution associated with nominal asset holdings which arises from unexpected inflation. Given the empirical profiles for nominal assets, households aged 48 or less benefit, with most gains accruing to households in their 30s as they have net nominal liabilities, while the remaining cohorts lose as they hold large stocks of nominal bonds and deposits. We observe gains associated with appreciation of real asset prices, the holdings of which rise sharply until around the age of retirement, and then decline.

Figure 1 Accounting effects of a monetary easing on impact by household age

Monetary policy has also indirect effects, operating mainly through the labour market. An expansion in economic activity boosts wages and employment, benefiting the working population. As Figure 1 reveals, this effect is sizable, especially for younger individuals.

Putting these effects together suggests that a monetary policy easing boosts resources available for spending for all age groups that we consider in our analysis, with most gains accruing to households aged around 60 as their housing and real assets positions peak around this age.

Remaining lifetime welfare

We now show that the analysis presented above, though still popular in the literature, can give us a misleading answer to who really gains or loses. A very important, though almost universally neglected argument is related to asset prices in the presence of life-cycle decisions. Whether and to what extent individuals benefit from an increase in asset prices depends not only on the current net position, but also on whether they are in the process of accumulating or decumulating a particular type of assets. For example, a homeowner might not necessarily gain from house price appreciation if he/she plans to move to a bigger house, because the planned increase in housing becomes costlier. A similar argument applies to accumulation of financial assets before retirement and their decumulation during the remaining lifetime.

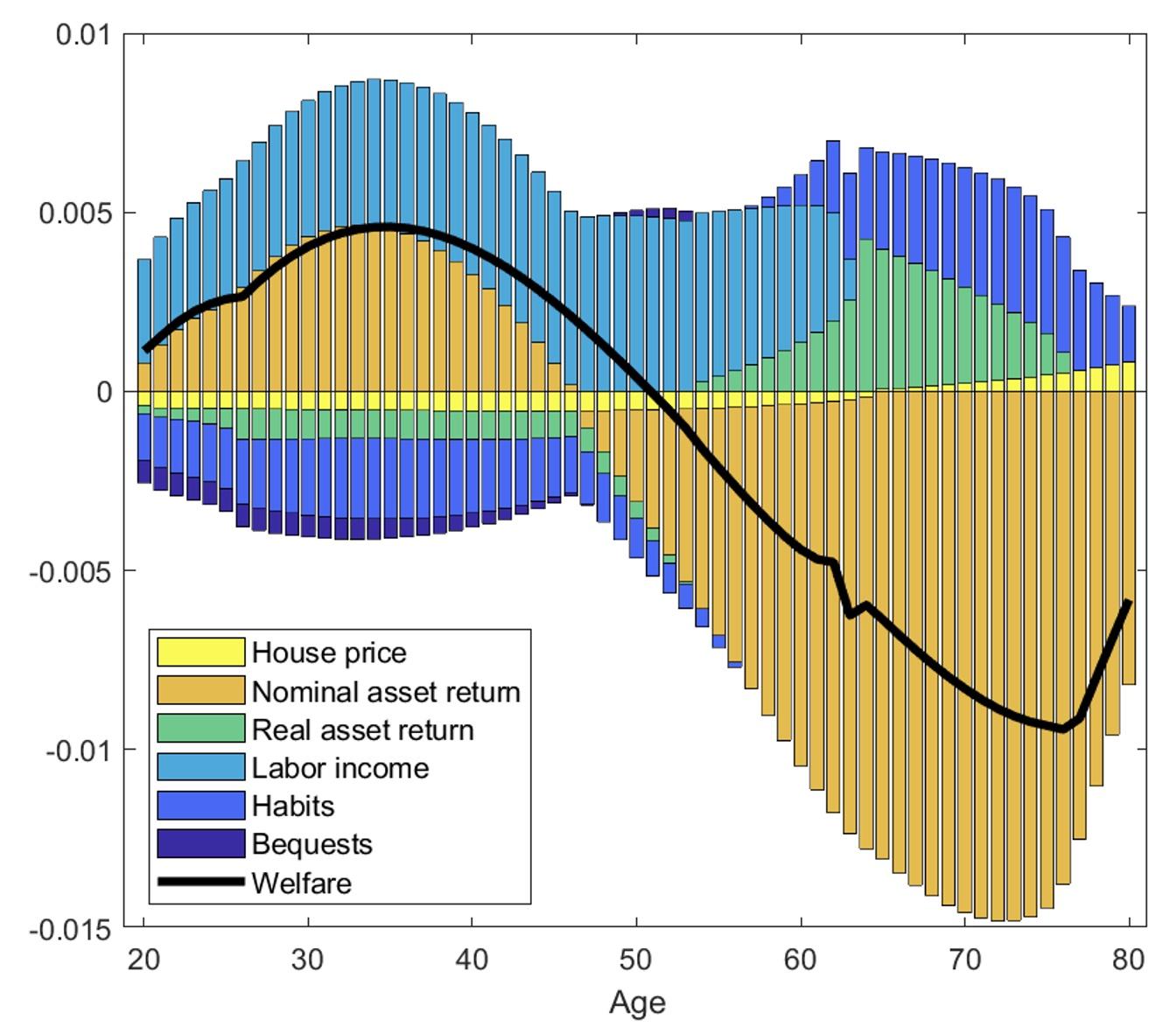

Figure 2 Effects of a monetary easing on remaining lifetime welfare by household age

Figure 2 plots the appropriately calculated redistributive effects, which we derive using the concept of remaining lifetime welfare. Unlike in Figure 1, the impact of changes in house prices is negative for households below 65 and only positive thereafter. This is because what matters for welfare is not only the level of assets, but also their accumulation pattern, which is in our model dictated by life-cycle motives. Increasing house prices benefit agents only if they are in the process of running down their housing stock, and people tend to accumulate this asset up to around retirement.

The most important driver of redistribution is associated with nominal asset holdings, which is positive for young households and negative thereafter. Clearly, this pattern is related to the fall in the real value of nominal assets due to surprise inflation. The effect is thus positive for young (debtor) and negative for old (creditor) households. However, as is obvious from comparing with Figure 1, there must be something else at play. The youngest households (below 35) are in the process of lowering their nominal asset holdings as they increase their debt, middle-aged households accumulate them, while the oldest households (over 70) decumulate again. Since these adjustments happen at a higher price (as the interest rate is persistently lower), the youngest and oldest benefit additionally at the expense of middle-aged agents.

As regards the effect associated with real assets, there are two competing forces. First, their owners benefit from the high ex post rate of return on impact, which mainly reflects the increase in the price of capital, and this is the effect we have seen in Figure 1. However, simultaneously, households that want to follow their life-cycle pattern of real asset accumulation must do it by paying more for additional claims on capital. Consequently, being on the accumulation path of real assets is harmful for welfare. The net effect is hence negative for all households aged 54 and below. Only after this age do the initial capital gains outweigh the additional accumulation cost, and the gains are highest for capital-rich households in their mid-sixties, who start decumulating real assets.

The labour income component is universally positive for working age households who benefit from the persistent macroeconomic expansion that follows a monetary easing, which drives employment and wages up. The difference between the shape of this component and its on-impact counterpart from Figure 1 is mainly due to future expected gains, which decline for agents close to retirement.

The net outcome of all welfare components is denoted with the black line. Clearly, younger households gain from a monetary easing, while older ones lose. Especially when contrasted with Figure 1, our estimates show the perils of relying on conclusions based only on the initial impact on wealth or income. This is particularly true for the effect via housing wealth, but also for the aggregate picture, where everybody seems to be a winner if only the initial price adjustments are considered. More generally, the difference between the picture plotted by Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate in a life-cycle context the quantitative importance of the insight made by Auclert (2019), according to whom what matters for redistribution is the distribution of maturing assets and liabilities. This insight is missing in the literature where all heterogeneity arises due to idiosyncratic shocks.

Not everyone is happy

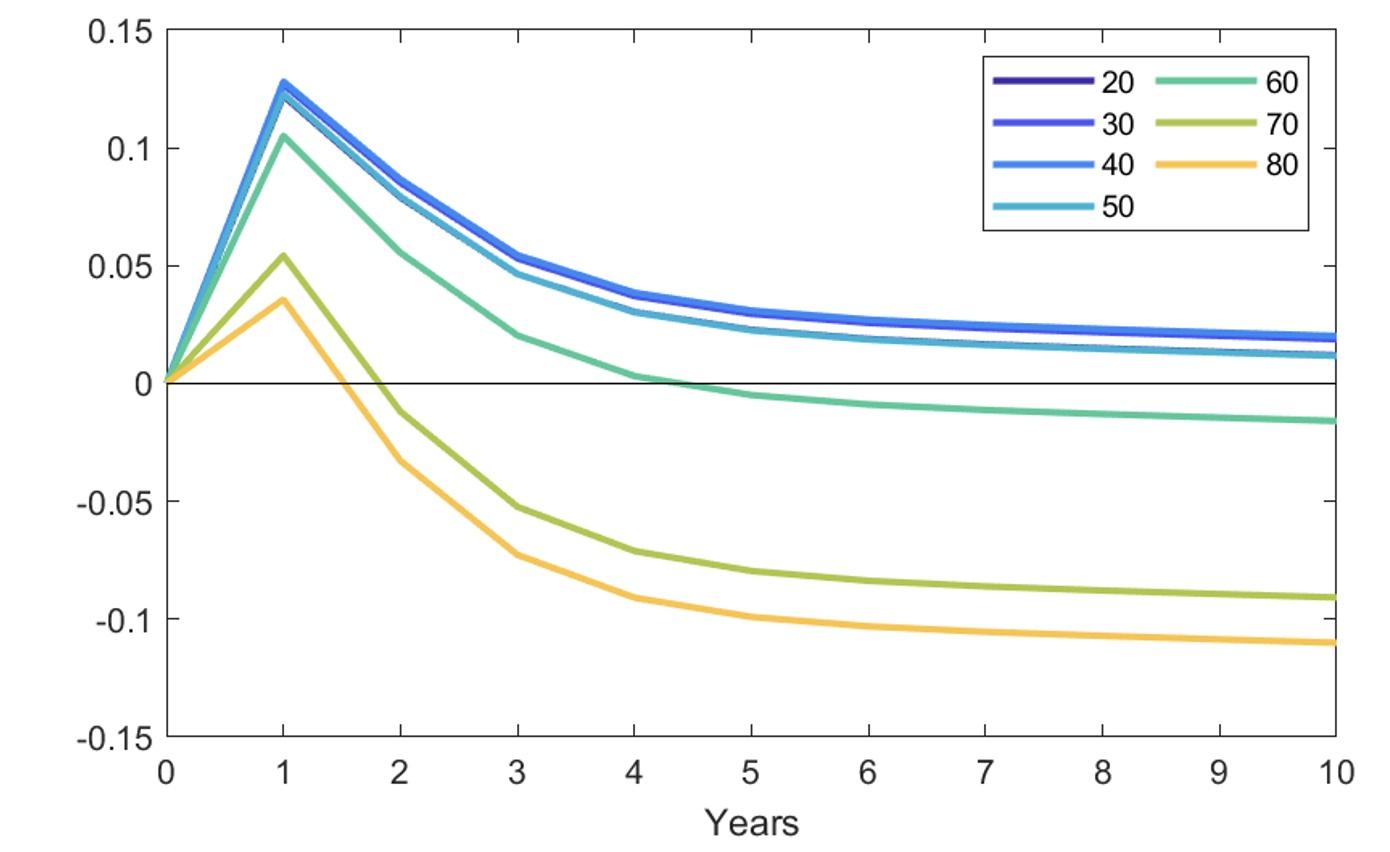

In reaction to the direct effects of monetary shocks associated with asset prices, and indirect ones coming from general equilibrium reactions of other prices – wages in particular – households modify their allocations. Figure 3 shows how selected cohorts adjust their consumption following a negative interest rate shock. The reactions are consistent with the estimated welfare effects described in the previous section. Following a monetary policy easing, younger and middle-aged households become wealthier in the remaining lifetime sense, and so can increase consumption and accumulate more housing. Older generations become poorer and so, except for a short-lived boost due to intertemporal motives, their consumption remains permanently depressed, reflecting loss in their retirement savings.

Figure 3 Response of consumption to monetary easing by age cohorts

The key takeaway from our analysis is that lifecycle aspects are important to appropriately evaluate welfare redistribution due to shocks and policies, and monetary adjustments in particular. It highlights that a monetary easing, while having positive effects on average, can leave a substantial part of population actually worse off. This outcome squares nicely with the recent survey-based evidence from the UK discussed by Bunn et al. (2020). They show that elderly households were much less satisfied with the monetary expansion which followed the financial crisis.

References

Amberg, N, T Jansson, M Klein, and A Rogantini Picco (2021), “Five facts about the distributional income effects of monetary policy”, Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper No. 403.

Andersen, A. L, N Johannesen, M Jørgensen, and J-L Peydró (2020), “Monetary policy and inequality”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15599.

Auclert, A (2019), “Monetary policy and the redistribution channel”, American Economic Review 109(6): 2333-67.

Bielecki, M, M Brzoza-Brzezina, and M Kolasa (2021), “Intergenerational redistributive effects of monetary policy”, Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming.

Bunn P, A Haldane, and A Pugh (2020), “Has monetary policy made you happier?”, Staff Working Paper No. 880, Bank of England.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, L Kueng, and J Silvia (2017), “Innocent bystanders? Monetary policy and inequality”, Journal of Monetary Economics 88(C): 70-89.

De Nardi, M (2015), “Quantitative models of wealth inequality: A survey”, NBER Working Paper 21106.

Ilzetzki, E (2021), “Monetary policy and inequality”, VoxEU.org, 18 August.

Kaplan, G, B Moll, and G Violante (2018), “Monetary policy according to HANK”, American Economic Review 108(3): 697-743.

Kuhn, M, and J Rios-Rull (2016), “2013 update on the U.S. earnings, income, and wealth distributional facts: A view from macroeconomics”, Quarterly Review, April: 1–75.

Slacalek, J, O Tristani, and G Violante (2020), “Household balance sheet channels of monetary policy: A back of the envelope calculation for the euro area”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 115: 103879.