Publicly provided services lack an explicit pricing mechanism to allocate scarce services to users. Instead, formal or informal barriers to access are often used to manage demand for services. For example, many public specialist health services are accessed through referrals from a general practitioner, who serves as the gatekeeper. Services such as social housing often manage demand through waiting lists.

In addition to deliberate barriers, unintentional barriers from imperfect information affect the uptake of services. Several studies have documented how barriers created by bureaucracy or information have a non-trivial impact on service use (Hastings and Weinstein 2008, King 2012, Bettinger et al. 2012, Finkelstein and Notowidigdo 2019).

Furthermore, when public services are (imperfect) substitutes, any access barriers to one service may also affect the uptake of other related services, possibly leading to inefficiencies in resource allocation to these services and in the uptake of these services by users.

Services available to victims of domestic violence provide an example of how access barriers across related services may affect the uptake of these services. Barriers to accessing non-police support services – such as refuge housing, counselling, and practical support with general safety measures – may arise for reasons including lack of knowledge of existing services, lack of clarity around what different services offer, and barriers due to gatekeepers.

In contrast, accessing police services is relatively frictionless for police-reported cases of domestic violence. When access to support services is made easier, how does this affect the use of police services and outcomes for victims of domestic violence?

In a recent study (Foureaux Koppensteiner et al. 2023), we evaluate an intervention that reduced the barriers to accessing non-police support services for victims of police-reported domestic violence. With a large UK police force, we ran a randomised controlled trial of an intervention designed to improve access to non-police support services. The intervention focused on repeat victims who had experienced three or more police callouts for violence over the previous year. We evaluated both the behavioural response of victims and its effect on the demand for police services, and outcomes reflecting the wellbeing of victims and subsequent household violence.

The randomised controlled trial builds on literature evaluating policing interventions to improve outcomes for victims of domestic violence. A small number of studies focus on interventions targeting perpetrators, for example on perpetrator arrest (Amaral et al. 2023). Other studies have focused on victims, for example through secondary responder programmes, with mixed results (Petersen et al. 2022). We studied an intervention specifically designed to remove barriers victims face when accessing support services.

The intervention and support services uptake

The intervention provided victims of police-reported domestic violence with a caseworker – formally known as an engagement worker – who offered information about support services and helped victims access them. Victims were initially contacted by a caseworker via telephone, and if the victim agreed, a face-to-face visit was arranged. The caseworker is not a police officer but has expertise in the services available to victims of domestic violence. The caseworker is embedded with the police and therefore has access to case and contact information. Caseworkers assisted victims by offering information, helping with paperwork, and providing necessary referrals. The trial ran for six months, resulting in more than one thousand cases in the subject pool.

Use of police and non-police services by victims

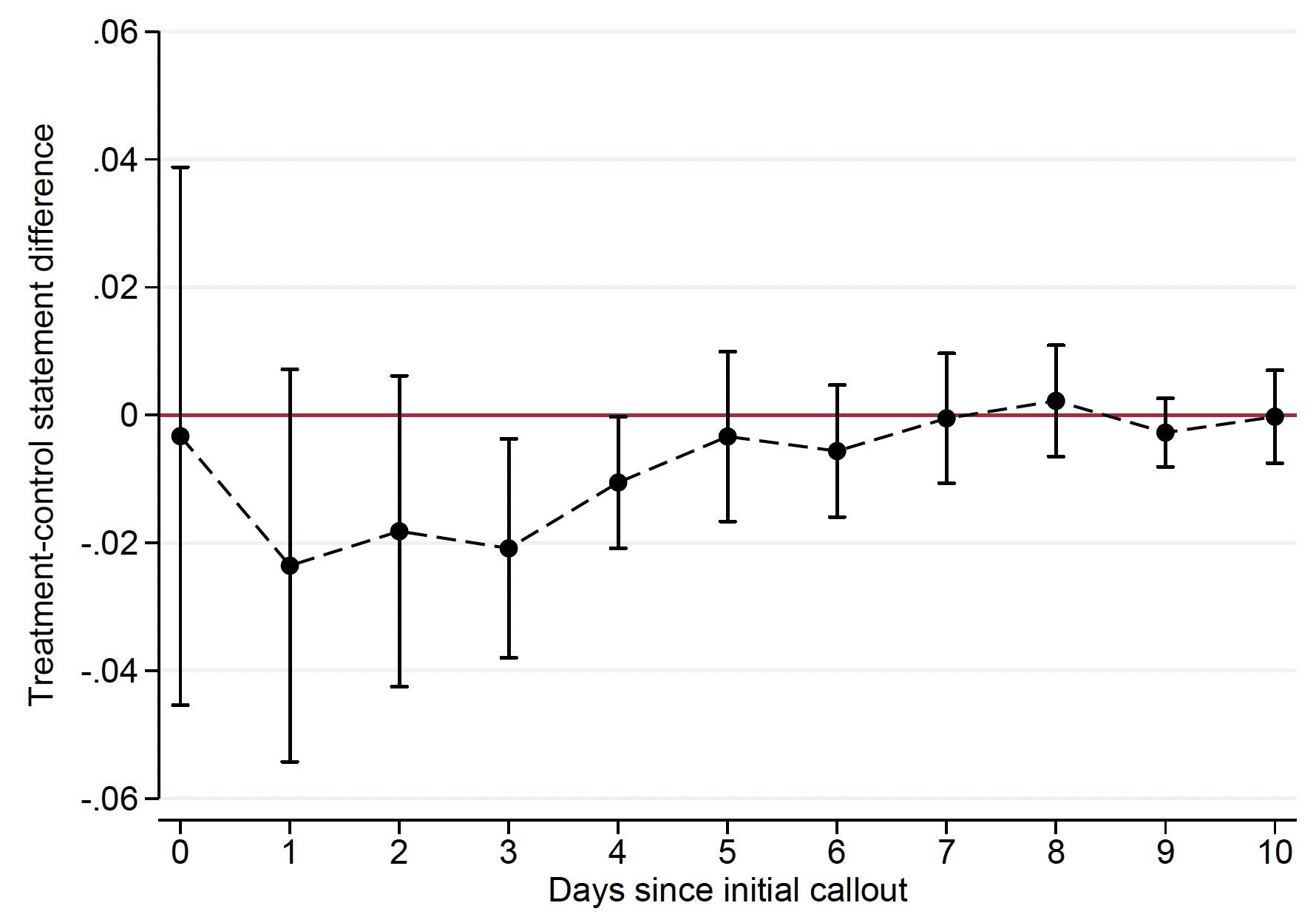

Victims who received the intervention were 21.7% less likely to provide police with a formal account of the incident, known as a witness statement. This is important, as witness statements are a critical, and often the only, piece of evidence in building a case against a perpetrator. Furthermore, this difference in statement provision only occurred after the treated group received the intervention, with no difference in the provision of statements at the initial police callout (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Difference in statement-making by days since initial callout

Source: Foureaux Koppensteiner et al. (2023).

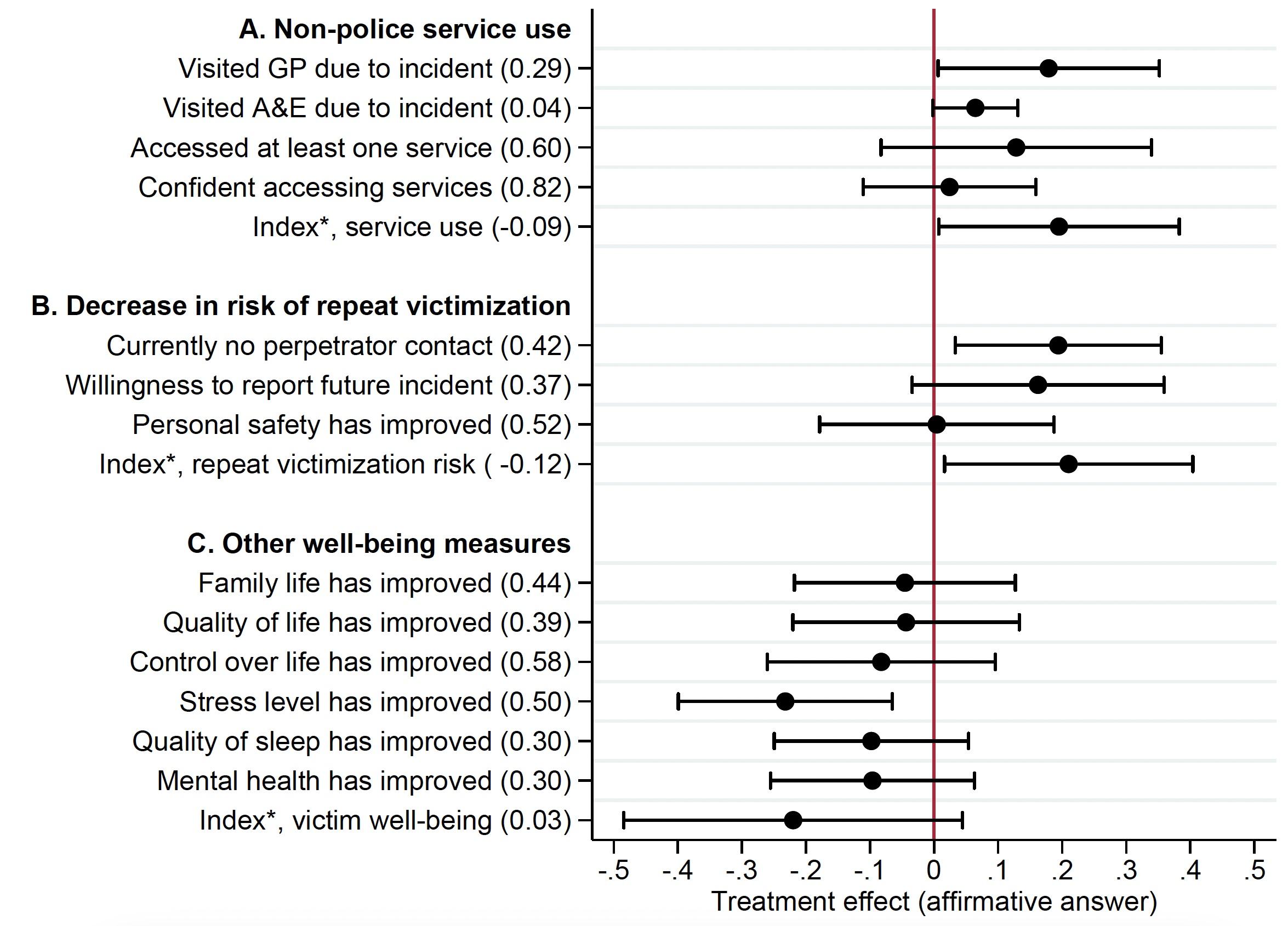

Survey evidence also showed that the treatment group was more likely than the control group to report using non-police support services (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Non-police services and victim wellbeing one month after intervention

Source: Foureaux Koppensteiner et al. (2023).

Taken together, these results are consistent with the victims in this study using non-police support services and police services as substitutes.

Witness statements are an important piece of evidence and a key input in the prosecution of perpetrators; the correlation between statement provision and criminal sanctions against a perpetrator is positive and strong. As a result, any decrease in the provision of witness statements may be concerning from a criminal justice viewpoint.

However, despite the decrease in statement provision, we did not find an effect of the intervention on criminal sanctions against a perpetrator (specifically, arrest by the police, charges by the Crown Prosecution Service, and sentencing by the courts). This suggests that for victims who made a statement in the control group – but not in the treatment group – the effect of their statement on criminal sanctions was low relative to other victims.

A plausible explanation for this is that these victims were more likely to retract their statements, making their statements inadmissible as police evidence. Indeed, we find that relative to the control group, treatment-group statements were 10.3 percentage points, or 84%, less likely to be retracted. We interpret this as the intervention increasing the efficiency of police-service utilisation by removing ineffective statements from the police officers’ service load.

Did the intervention make victims better off?

Based on survey evidence, we found several margins where the intervention improved outcomes for victims. The treatment group was more likely than the control group to report being no longer in contact with the perpetrator. The treatment group was 17.9 percentage points (61.7%) more likely than the control group to have visited their general practitioner, and 6.5 percentage points (163%) more likely to have visited the accidents and emergency department as a result of the initial incident. This is important because domestic violence has been shown to have devastating effects on the wellbeing and physical and mental health of victims (Bhuller et al. 2023); accessing health services shortly after an incident may help address those health concerns. Furthermore, Wilson et al. (2017) find that health improvements may lead to reductions in future violence.

Despite these positive effects on the victims’ safety, we found that treatment-group individuals reported higher stress than individuals from the control group, one month after the incident. It is possible that the increased stress is associated with changes in the victims’ personal circumstances as they engage with domestic-violence services.

While treatment lowered the predicted risk of revictimization, we did not find a significant effect on the frequency of repeat police-reported household violence over the following two years. However, we found suggestive evidence that, in the treatment group, subsequent reported cases were less severe. For example, reported violence-escalation risk scores by responding officers were 9.5% lower for the treatment cases than for the control cases.

Together with other measures of incident severity, this provides evidence consistent with the intervention leading to an increase in the victims’ willingness to report less severe subsequent incidents to the police.

Conclusion

Domestic violence is a problem of first-order importance across the world. In England and Wales, domestic violence makes up approximately one-third of all arrests made by police (Home Office 2019, Office for National Statistics 2019), creating substantial service demands on police forces. Removing barriers to other types of support services for domestic-violence victims may – in addition to improving access to services – alleviate the demand for police resources.

A limitation of this intervention is that it only improves access to support services for victims of police-reported violence, who are believed to be just a small fraction of all victims (Rainer et al. 2021). The barriers faced by victims who are already interacting with police are likely to be even bigger for victims who do not report incidents to the police.

The intervention changed the way victims interact with police and non-police services, but it also has implications for how police deal with victims following an incident. Often, it is the police officers responding to the initial police callout who inform victims of where they can go for assistance. This approach has been shown to be lacking (HMIC 2014), as officers rightly prioritise the immediate safety of the victim and the collection of evidence when attending a domestic violence incident. Furthermore, information about non-police services is complex and constantly changing, and police officers are less connected to service providers and gatekeepers.

The intervention studied here takes the responsibility to provide support from the responding officers and puts it in the hands of a specialist caseworker. Unlike existing services to signpost victims, the caseworker works within the police and has access to police information, allowing them to actively engage with victims shortly after an incident is recorded. Such victim-focused interventions may be useful when policing police-reported violence to address this serious and complex social issue.

References

Amaral, S, G Dahl, V Endl-Geyer, T Hener, and H Rainer (2023), “Arrests are effective in breaking the cycle of domestic violence”, VoxEU.org, 17 March.

Bettinger, E P, B T Long, P Oreopoulos, and L Sanbonmatsu (2012), “The role of application assistance in information in college decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(3): 1205–42.

Bhuller, M, G Dahl, K Løken, and M Mogstad (2023), “Domestic violence and the mental health and wellbeing of victims and their children”, VoxEU.org, 27 February.

Foureaux Koppensteiner, M, J Matheson, and R Plugor (2023), “The impact of improving access to support services for victims of domestic violence on demand for services and victim outcomes”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Finkelstein, A, and M Notowidigdo (2019), “Take-up and targeting: Experimental evidence from SNAP”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3): 1505–56.

HMIC - Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (2014), “Everyone’s business: Improving the police response to domestic abuse”.

Home Office (2019) “The economic and social costs of domestic abuse”, Home Office Research Report 107.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2019), “Domestic abuse prevalence and trends, England and Wales: Year ending March 2019”, statistical bulletin.

Petersen, K, R Davis, D Weisburd, and B Taylor (2022), “Effects of second responder programs on repeat incidents of family abuse: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis”, Campbell Systematic Reviews 18(1).

Rainer, H, F Siuda, and D Anderberg (2021), “Assessing the magnitude of the domestic violence problem during the COVID-19 pandemic”, VoxEU.org, 20 November.

Wilson, T E, R Pollak, G C Pauley, N Papageorge, B H Hamilton, and M Cohen (2017), “Health, human capital, and domestic violence”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.