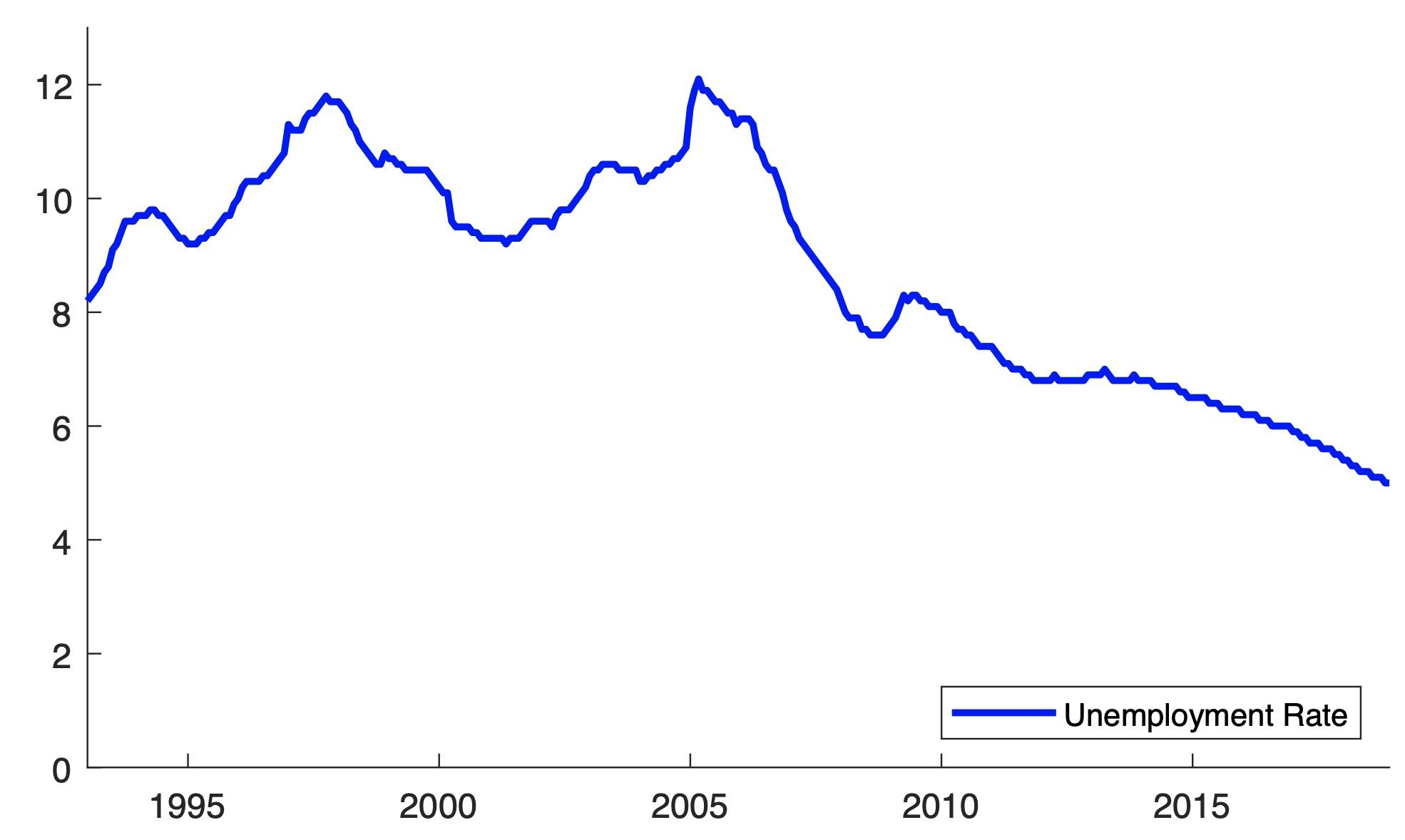

Germany’s unemployed declined from around 12% in 2005 to less than 6% today (see Figure 1). There is a vivid economic policy debate on the contribution of the Hartz labour market reforms and other factors for this decline (e.g. Burda and Hunt 2011, Dustmann et al. 2014). The macroeconomic effects of the unemployment benefit reform in 2005 have received a lot of attention in the scientific literature (e.g. Krause and Uhlig 2012, Krebs and Scheffel 2013a, b, Launov and Wälde 2013, Hochmuth et al. 2021, Hartung et al. 2022). By contrast, little attention has been devoted to the macroeconomic labour market effects of the reorganisation of the Federal Employment Agency (in German, Bundesagentur für Arbeit) in 2004 (for one rare exception, see Launov and Wälde 2016).

Figure 1 The registered unemployment rate in Germany

Source: OECD.

In Germany, unemployed workers register at the Federal Employment Agency, which is a public employment agency. The agency connects unemployed workers and those vacant jobs that are registered at the agency to establish matches. However, the majority of matches are established via private channels. According to data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), the Federal Employment Agency intermediated only around 11% of aggregate matches before the Hartz reforms. In 2004, the organisational structure of the agency was reformed as part of the third package of the Hartz labour market reforms (Hartz III, in short). In the new structure, every unemployed worker was assigned to one particular Federal Employment Agency caseworker. The number of unemployed workers that caseworkers were in charge of was reduced as part of the reform (see Jacobi and Kluve 2007 for details). Furthermore, caseworkers started to use sanctions if unemployed workers did not comply with search requirements or if they rejected job offers. It seems natural to expect that this organisational reform would put caseworkers in a better position to connect their assigned unemployed workers with vacant jobs in their database.

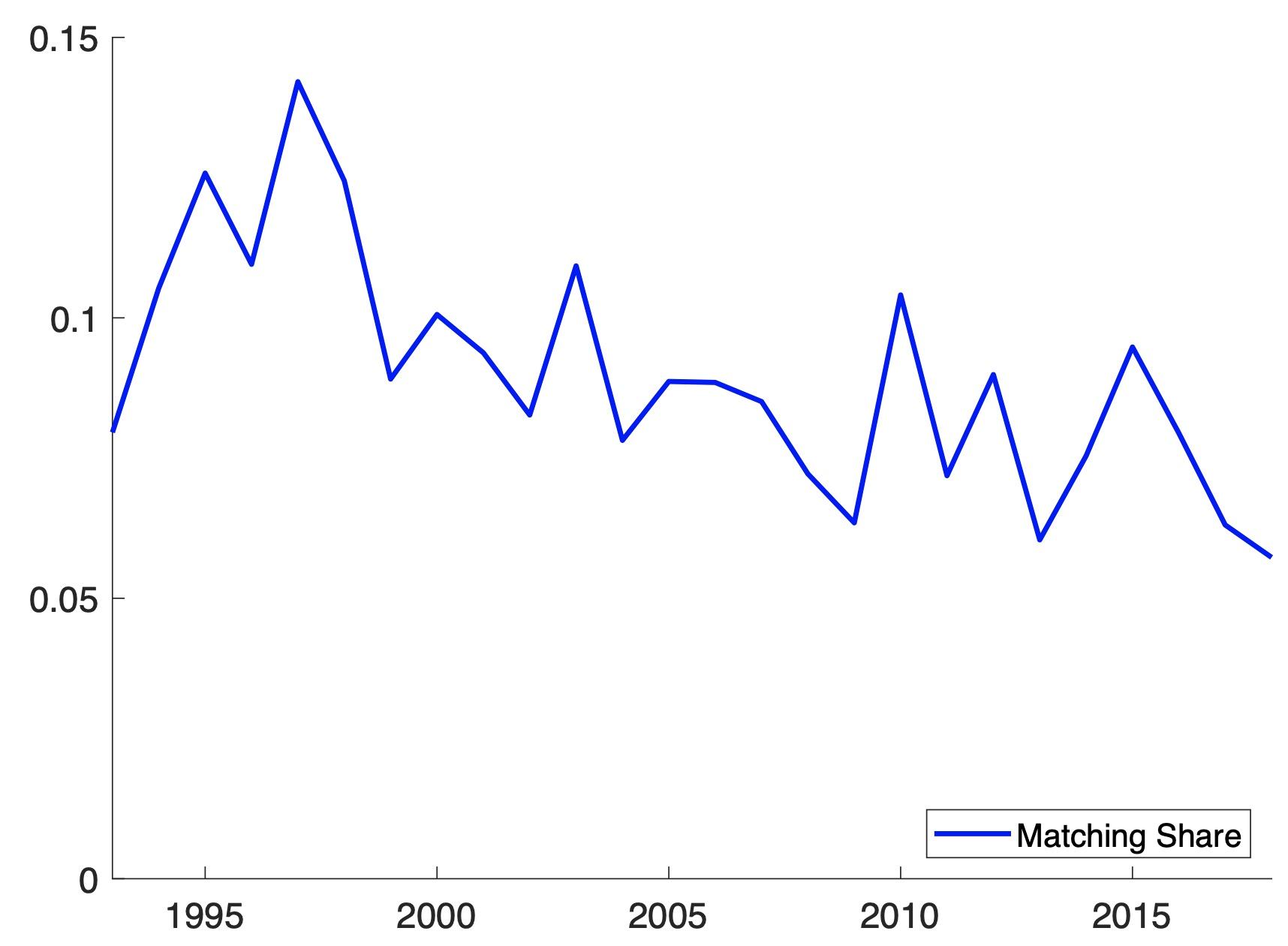

Maybe surprisingly, we show in Merkl and Sauerbier (2023) that the share of jobs that was intermediated via the Federal Employment Agency (‘matching share’, henceforth) was even smaller after the reform than before the reform (8% instead of 11%). Based on the SOEP, Figure 2 illustrates this finding. The decline of the matching share in the aftermath of the Hartz reforms is robust in various dimensions (e.g. when using the employer-sided IAB Job Vacancy Survey instead of the household-sided SOEP, looking at West Germany instead of Germany, or considering a longer time period prior to the reform). When we look at three different skill groups (low-, medium-, and high-skilled), we observe a decline in the matching share for each skill group. The matching share declined, for example, from 12% to 10% for medium-skilled workers. It is also worth mentioning that the decline of the Federal Employment Agency’s matching share cannot be explained by a time trend (see Merkl and Sauerbier 2023 for details).

Figure 2 Matching share, defined as the share of matches intermediated via the Federal Employment Agency

Note: Calculations are based on SOEP.

In Merkl and Sauerbier (2023), we analyse the Hartz labour market reforms through the lens of a newly proposed dynamic search-and-matching model. Our model contains a public matching market (in which all unemployed workers have to participate) and a private matching market (in which all firms participate). In addition, workers decide whether they want to use the private matching market, and firms decide whether they want to use the public matching market.

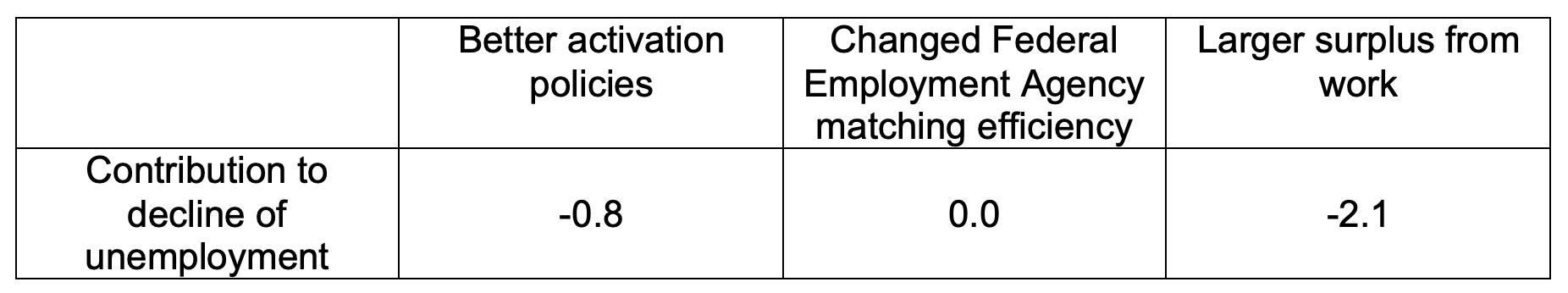

In our quantitative exercise, we match the decline of the Federal Employment Agency’s matching share, the increase of the agency’s vacancy share (i.e. the share of vacancies posted at the agency), and the decline of unemployment from the data by using three instruments (namely, changed Federal Employment Agency matching efficiency, different activation policies, and a different surplus from work). We show that better activation policies contributed 0.8 percentage points to the decline in German unemployment (see Table 1). By contrast, the matching efficiency of the Federal Employment Agency remains at a similar level as before the reform and thereby does not affect aggregate unemployment. Intuitively, an increase in the agency’s matching efficiency would increase the matching share. However, this would stand in contrast to the observed fall of the matching share. Finally, a larger surplus from work (defined as the difference between production per worker and unemployment benefits) contributed around two percentage points to the decline of unemployment. This is certainly partly driven by the fourth package of the Hartz reforms (Hartz IV, in short), which reduced benefits for long-term unemployed workers.

Table 1 Simulated individual effects of three policy exercises on unemployment (in percentage points)

Source: Merkl and Sauerbier (2023).

Intuitively, after the Hartz III reform, the Federal Employment Agency did a much better job in terms of activating unemployed workers. In our model, this is represented by larger incentives to use the private matching market. In reality, we expect two channels to have been at work. First, caseworkers may have provided better support for the application process (e.g. in terms of better job counselling), which reduced the costs of the private search. Second, caseworkers may have sanctioned registered unemployed in case of low private search activity, which increased the costs of not searching privately. Descriptive data indeed show substantial sanctioning activity in the aftermath of the Hartz III reform. Both more support and more sanctions for unemployed workers were in line with the new strategy of the Federal Employment Agency, as part of the Hartz reforms (‘Fordern und Fördern', in German).

In other words, our quantitative model exercise shows that instead of connecting unemployed workers and job vacancies directly, the restructured Federal Employment Agency helped and pushed unemployed workers to use the private matching market more actively. As caseworkers knew their customers better in the newly restructured organisation, they were able to support and challenge them more.

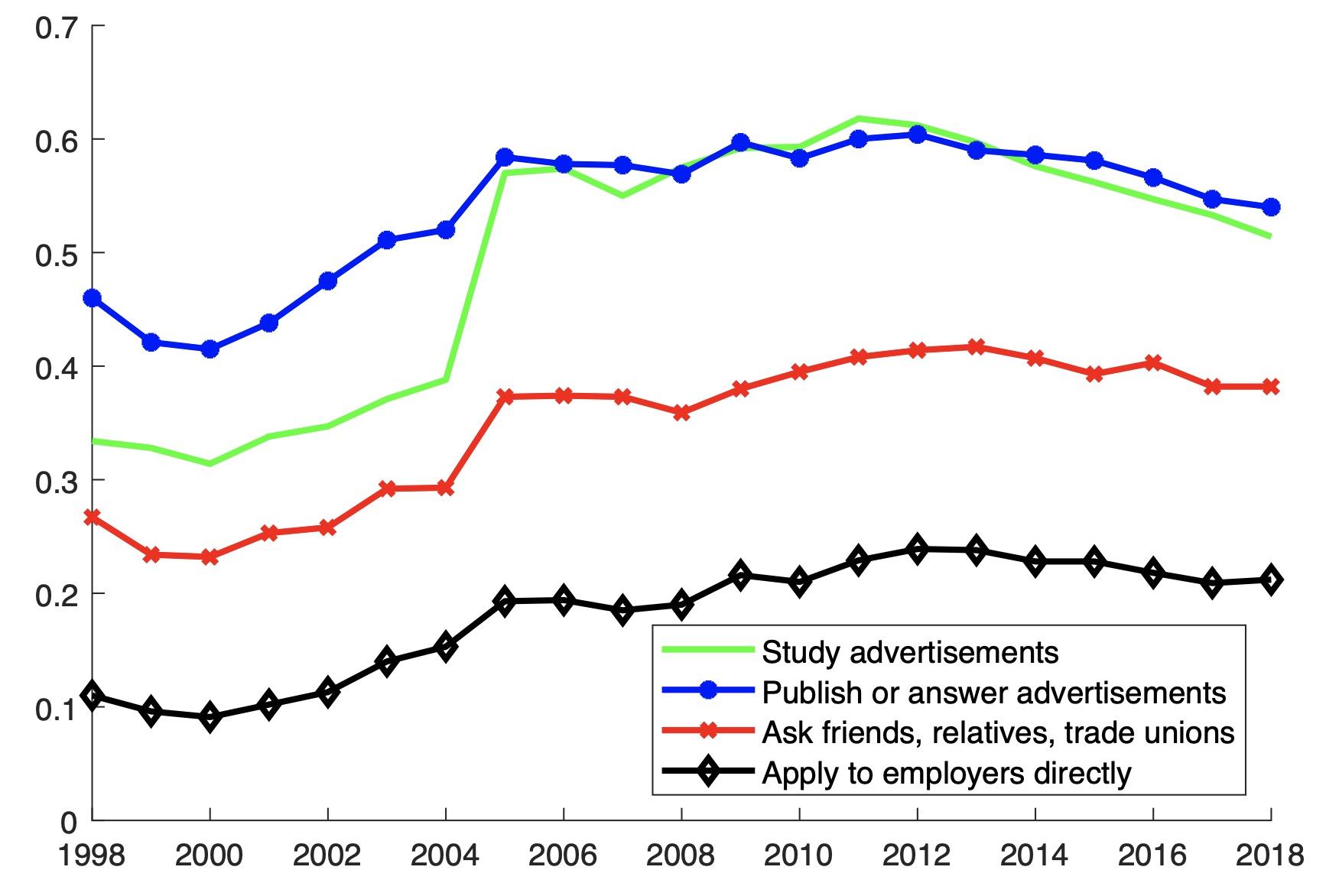

Our model-based conclusion that a stronger usage of the private matching market was important is supported by causal microeconometric evidence from Holzner and Watanabe (2021), who use the staggered role out of the Hartz III reform for identification. They show that the reform indeed decreased the fraction of newly unemployed workers receiving vacancy referrals from the Federal Employment Agency. Furthermore, we show in Figure 3 that the usage of private search channels increased at the time of the Hartz reforms.

Figure 3 Share of unemployed who uses the named search channels

Source: European Union Labor Force Survey, Eurostat.

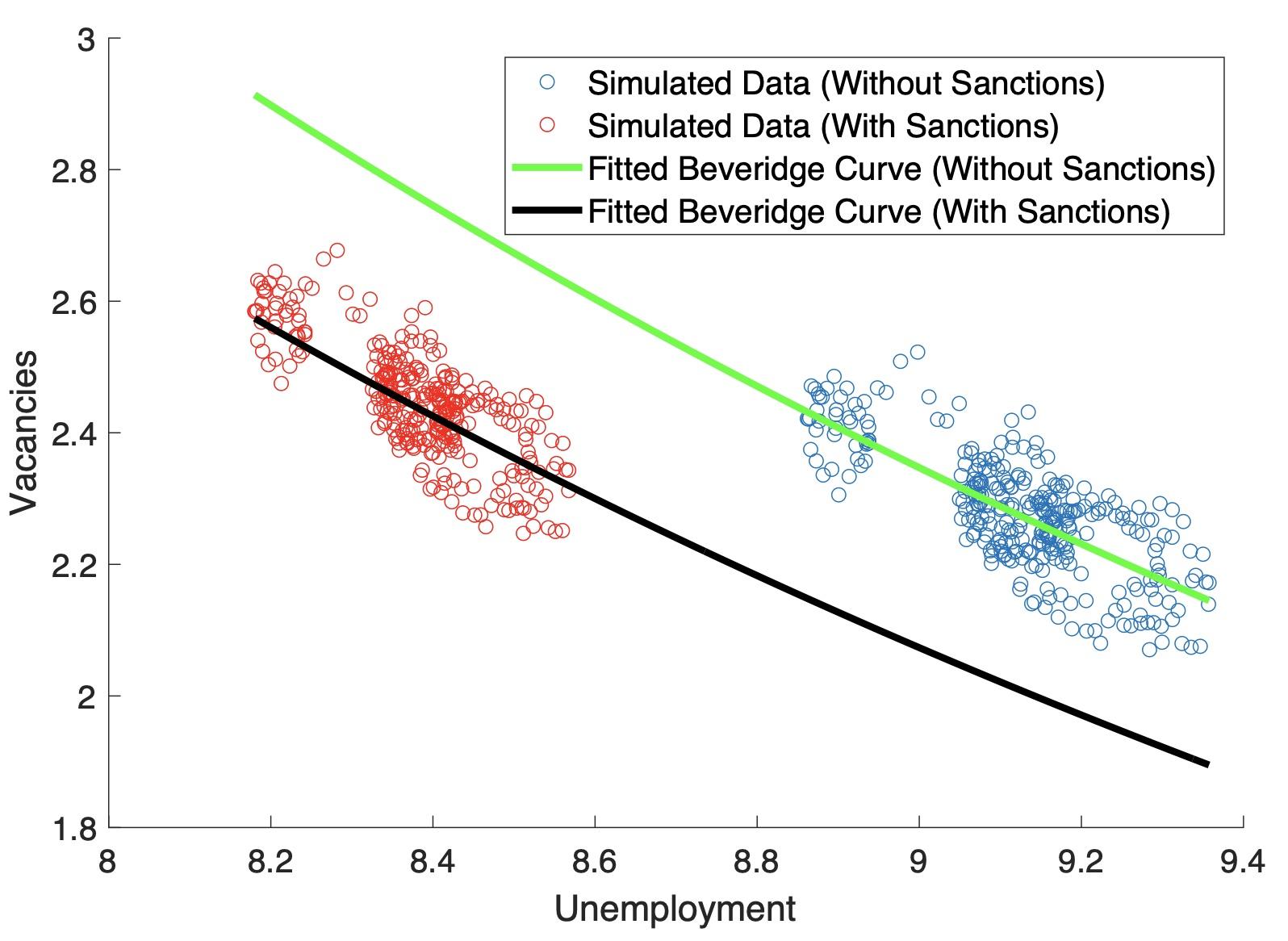

Interestingly, better activation policies in the order of magnitude identified in our quantitative model matching exercise lead to a significant leftward shift of the Beveridge curve in our simulation (see Figure 4). A similar shift can be found in the data at the time of the Hartz reforms. Such a shift of the Beveridge Curve is typically associated with an increase in aggregate matching efficiency in macro-labour economics. However, in our model with two matching markets, it is the result of a compositional shift. Due to a larger fraction of unemployed workers who search via the (more efficient) private market, aggregate matching looks more efficient.

Figure 4 Simulated Beveridge curve with (left-hand side) and without improved activation policies (right-hand side)

Source: Merkl and Sauerbier (2023).

To sum up, the restructuring of the German Federal Employment Agency did not improve its capability to match searching workers with vacant jobs. Instead, the new structure allowed caseworkers at the agency to monitor and activate unemployed workers better. This is an important lesson for other European countries where typically a large fraction of workers use a public employment agency. The German example does not teach how to improve public intermediation activity via a public employment agency. Instead, it teaches how to restructure the agency such that private search activity increases, job-finding rates increase, and aggregate unemployment falls.

References

Burda, M and J Hunt (2011), “The German Labour-Market Miracle”, VoxEU.org, 2 November.

Dustmann, C, B Fitzenberger, U Schönberg and A Spitz-Oener (2014), “From Sick Man of Europe to Economic Superstar: Germany’s Resurgence and the Lessons for Europe”, VoxEU.org, 3 February.

Hartung, B, P Jung and M Kuhn (2022), “Unemployment Insurance Reforms and Labor Market Dynamics”, mimeo, Universität Bonn.

Hochmuth, B, B Kohlbrecher, C Merkl and H Gartner (2021), “Hartz IV and the Decline of German Unemployment: A Macroeconomic Evaluation”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 127: 104114.

Holzner, C and M Watanabe (2021), “The Wage Effect of Vacancy Referrals from the Public Employment Agency”, mimeo.

Jacobi, L and J Kluve (2007), “Before and after the Hartz Reforms: The Performance of Active Labor Market Policy in Germany”, Journal for Labour Market Research 40(1): 45–64.

Krause, M U, and H Uhlig (2012), “Transitions in the German Labor Market: Structure and Crisis”, Journal of Monetary Economics 59(1): 64–79.

Launov, A and K Wälde (2013), “Estimating Incentive and Welfare Effects of Nonstationary Unemployment Benefits”, International Economic Review 54(4): 1159–1198.

Launov, A and K Wälde (2016), “The Employment Effect of Reforming a Public Employment Agency”, European Economic Review 84: 140–164.

Merkl, C and T Sauerbier (2023), “Public Employment Agency Reform, Matching Efficiency, and German Unemployment”, IMF Economic Review, forthcoming.

Scheffel M and T Krebs (2013a), “German Labour Reforms: Unpopular Success”, VoxEU.org, 20 September.

Scheffel, M and T Krebs (2013b), “Macroeconomic Evaluation of Labour Market Reform in Germany”, IMF Economic Review 54(4): 1159–1198.