Active labour market programmes are expected to promote employment and foster earnings growth. They have been suggested as remedies for jobs lost during economic downturns or because of structural change stemming from automation. It is not surprising, then, that the effectiveness of these programmes has been studied extensively. Meta-analyses reveal effect sizes that vary considerably depending on context (Greenberg et al. 2003, Card et al. 2018, Yeyati et al. 2019a, 2019b). Despite the abundance of research in this area, none of these studies focuses on programmes designed specifically for Indigenous populations. Understanding when and how these programmes work for Indigenous peoples is of global importance, as there are over 370 million Indigenous peoples worldwide, and countries such as the US, Australia, and Canada currently direct federal funding to labour market programmes designed to address their unique needs and challenges.

Although differences across Indigenous populations may limit the generalisability of any one analysis, studying the institutional arrangements that facilitate effective labour market programmes contributes broadly to existing work emphasising the importance of context. In a recent working paper, we evaluate a unique active labour market programme for Indigenous groups in Canada to understand the factors that both facilitate and hamper improvements in individuals’ labour market outcomes following programme participation (Feir et al. 2022).

The Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS) operated from 2010 to 2018 and directed federal funding to Indigenous partner organisations delivering active labour market programmes that were responsive to local labour market demand. ASETS represented 3% of total federal spending on Indigenous services, and was succeeded by a programme similar in scope and purpose called the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training programme. To evaluate whether more intensive programmes improve earnings relative to lighter-touch interventions, we use new data that links programme information for the population of ASETS participants to longitudinal tax and employment insurance records.

Following an approach used by Andersson et al. (2016), we compare labour market outcomes in the two years following ASETS participation between two groups distinguished by high- and low-intensity participation. High-intensity programmes are longer in duration and provide either skills development, wage subsidies, or job creation partnerships, while low-intensity programmes include employment assistance and job counselling services. We use propensity score reweighting methods to ensure that our comparison groups are balanced in terms of a rich set of pre-participation outcomes including previous labour market programme participation and up to ten years of earnings histories. We focus primarily on the programme’s effects on earnings, though our paper also considers employment as an important outcome.

In Canada, there are three constitutionally recognised Indigenous groups: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. First Nations people are further legally classified as “Status” or “non-Status”. We study the effects of ASETS separately for Métis, Status First Nations, and non-Status First Nations men and women. The federal government exercises legislative jurisdiction over Status First Nations and on reserves – land set aside for the sole use of Status First Nations – even in policy areas such as income assistance that typically fall under provincial jurisdiction. These jurisdictional arrangements mean that Indigenous people who live in the same local area may work in labour markets governed by different institutions.

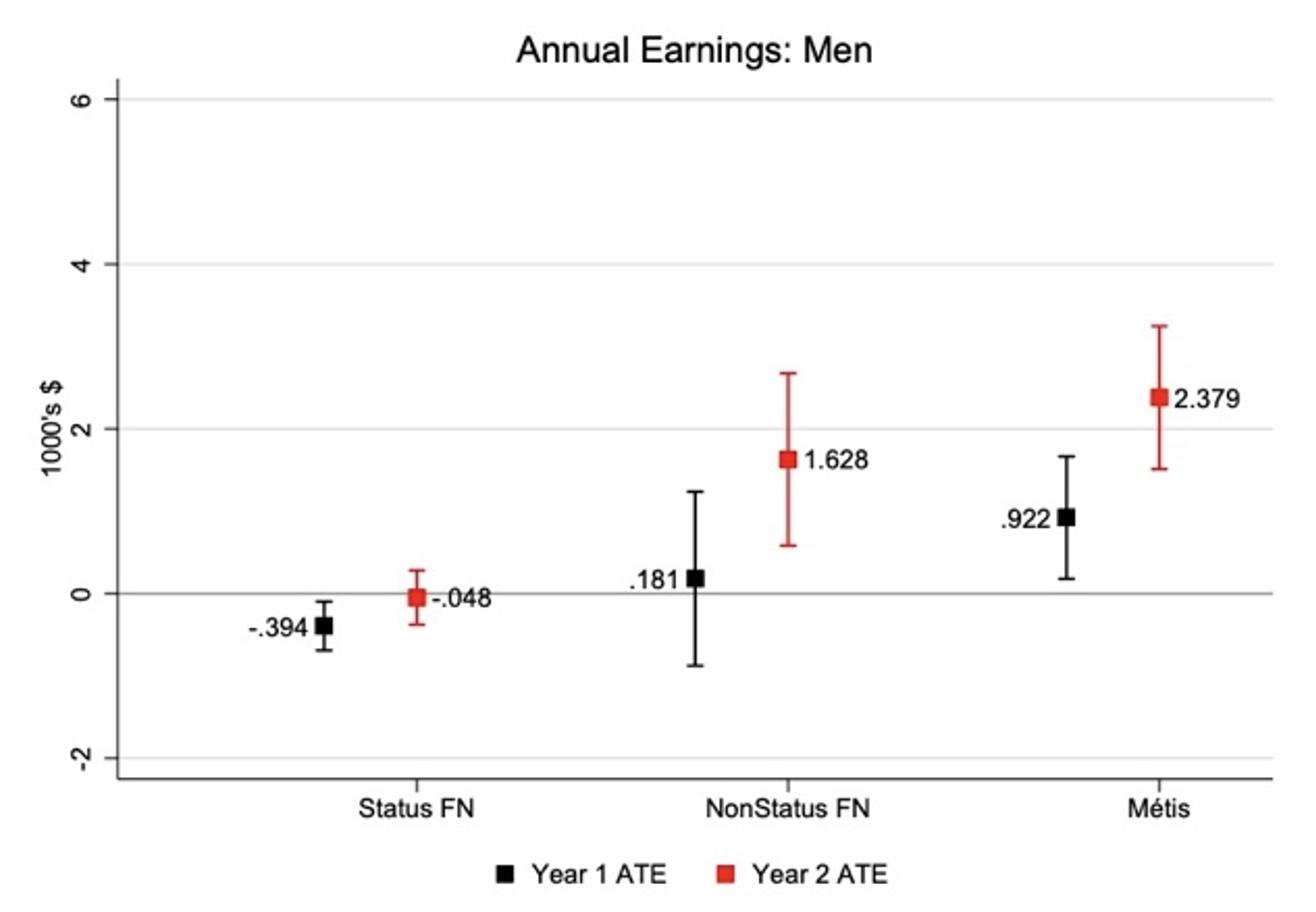

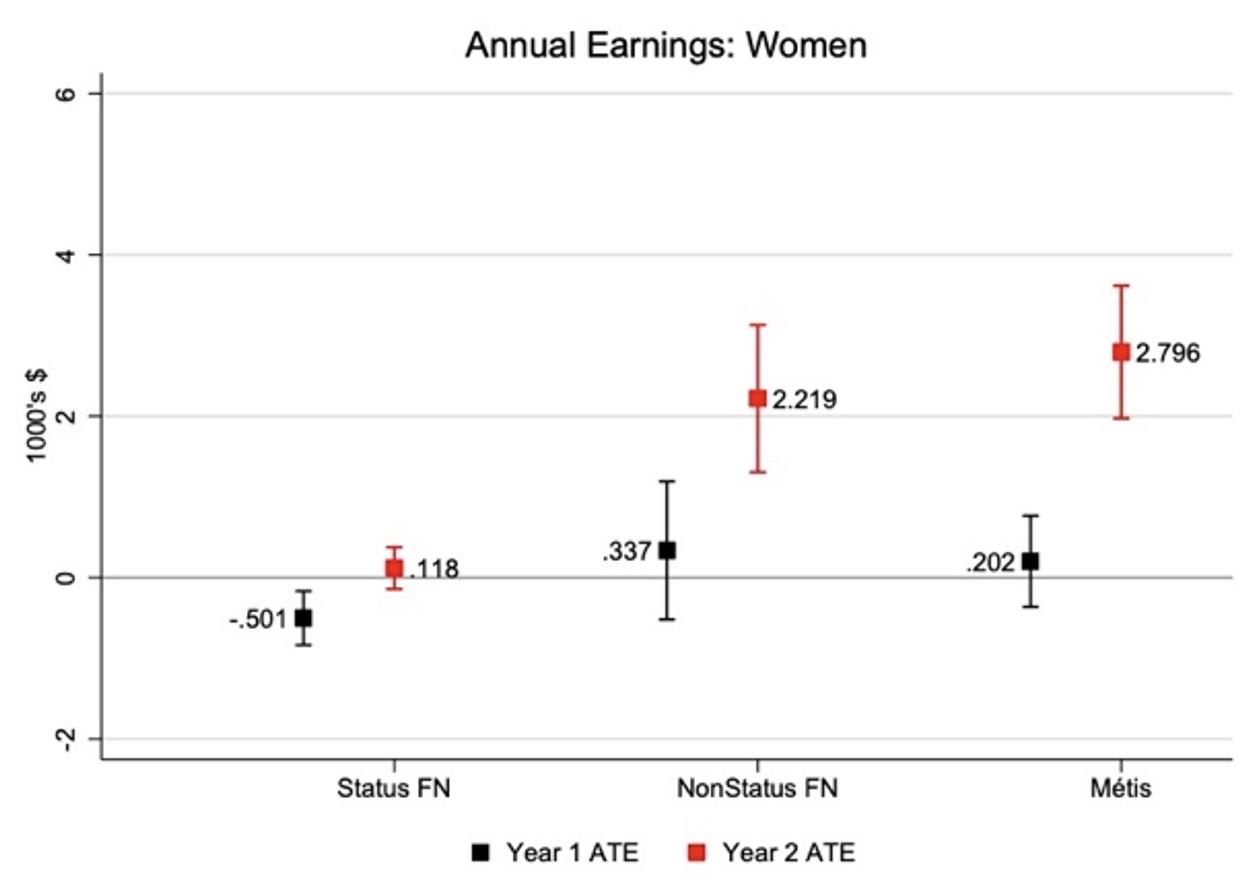

We find substantial differences in the earnings returns to high-intensity participation across three distinct Indigenous population groups (see the left panel of Figure 1 for men and the right panel for women). High-intensity Métis participants had earnings that were upwards of $3,300 CAD greater than low-intensity Métis participants two years following ASETS participation. High- intensity non-Status First Nations participants also experienced returns to earnings in the realm of $2,000–$2,700 CAD. Status participants who participated in high-intensity programmes did not experience a growth in earnings relative to low-intensity participants. The explanation for these differences in returns across population groups is arguably due to the fact that each Indigenous group is served by different service delivery organisations, facing different labour market environments, and under different jurisdictional authority. Specifically, we focus on why Métis participants experienced higher than average returns to high-intensity participation and why Status First Nations participants experienced lower than average returns.

Figure 1 The impact of high- relative to low-intensity ASETS participation on earnings

Notes: The markers represent estimates of the average treatment effect. Black markers depict estimates one year after ASETS participation and red markers represent two years following participation.

One potentially important explanation for why the Métis received greater earnings returns to high-intensity programmes may be the fact that Métis service delivery organisations tend to be more centralised than other organisations and, as a result, may have greater potential for offering additional wrap-around services. In addition, unlike First Nations participants, Métis participants did not have access to additional federal funding for post-secondary education (PSE) during the period of our analysis. This means that Métis service delivery organisations may have been more likely to provide support for PSE through ASETS, whereas First Nations service delivery organisations may have referred both high- and low-intensity participants to the Post-Secondary Student Support Program for additional post-secondary funding. Consistent with this possibility, our data suggest that Métis participants spent longer in skills development programmes compared to both Status and non-Status First Nations participants.

One of the most obvious factors differentiating Status First Nations from other Indigenous groups has to do with their unique position in Canada’s legal landscape. The Federal government, rather than the provinces, have traditionally had explicit jurisdiction over Indian reserves and First Nations peoples. The Indian Act, which applies to most Status First Nations people and lands, creates legislative and bureaucratic hurdles to establishing private enterprises on reserves. We show that high-intensity Status First Nations participants who worked on- reserve prior to participating in ASETS did not experience gains in earnings relative to low- intensity participants unless they transitioned to off-reserve employment in the post-ASETS period. Similarly, high-intensity ASETS participants who worked off-reserve in the pre-ASETS period experienced earnings returns when they continued to work off-reserve in the post- participation period.

We argue that the institutional barriers to doing business on reserves has resulted in a lack of labour demand, which has implications for the effectiveness of demand-driven labour market programming. Until these barriers are dismantled, active labour market programmes may not generate returns to earnings. Of course, we are unable to speak to some of the broader impacts of participation, such as increases in motivation, career aspirations, life satisfaction, or community wellbeing. Indeed, many of these important outcomes have been shown to ameliorate labour market outcomes (Schossler and Shanan 2022) in other settings.

References

Andersson, F, H J Holzer, J I Lane, D Rosenblum and J A Smith (2016), “Does Federally- Funded Job Training Work? Non-experimental Estimates of WIA Training Impacts Using Longitudinal Data on Workers and Firms”, CESifo Working Paper Series 6071, Munich.

Card, D, J Kluve and A Weber (2018), “What works? A meta-analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations", Journal of the European Economic Association 16(3), 894–931.

Feir, D, K Foley and M E C Jones (2021), “Heterogeneous Returns to Active Labour Market Programming for Indigenous Populations”, NBER Working Paper No. 30158.

Feir, D, K Foley and M E C Jones (2021), “The Distributional Impacts of Active Labor Market Programs for Indigenous Populations”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 111, 216–220.

Greenberg, D H, C Michalopoulos and P K Robins (2003), “A meta-analysis of government- sponsored training programs”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review 57(1), 31–53.

Levy Yeyati, E, M Montané and L Sartorio (2019), “What works for active labor market policies?”, Harvard University CFID Working Paper No. 358.

Levy Yeyati, E, M Montané and L Sartorio (2019), “Understanding what works for active labour market policies?”, VoxEU.org, 03 September.

Schlosser, A and Y Shanan (2022), “Fostering soft skills in active labour market programmes: Evidence from a large-scale randomised control trial”, VoxEU.org, 09 June.