The context

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, job transitions of personnel in US banking regulation between the regulatory and private sector—or the revolving door—have come under intense scrutiny and have been blamed by economists (Johnson and Kwak 2010), legal scholars (John Coffee in Financial Times 23 April, 2012) and policymakers (Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, Section 968) alike for distorting regulators’ actions on behalf of banking industry interests. Other commentators have downplayed distortions of the revolving door in banking regulation and presented a more benign viewpoint of revolving doors as a means for regulatory agencies to attract higher ability and skilled workers. For example, regulatory agencies may benefit from private industry insiders with an in-depth knowledge of banking practices and thus may hire workers from the industry. On the other hand, bankers in the private sector may better understand compliance with supervisory practices and regulations when employed in the government sector, and therefore may decide to transition to the government sector. Because of the difficulty in obtaining systematic data on job transitions in banking regulation, the general perception driving these discussions are mostly informed by anecdotes, which are often linked to former regulatory personnel transitioning to the private sector around apparent regulatory failures. In our recent paper (Lucca et al. 2014), we hope to offer more rigour to this debate by providing a first set of stylised facts related to incidence and drivers of the revolving door in US banking regulation.

Our study has two modest goals.

- First, we provide basic facts on worker flows between the banking regulatory and private sectors by examining worker transitions resulting from hiring and separations.

- Second, we characterise these flows in terms of their business cycle variation, job creation and destruction in the two sectors, and worker characteristics such as human capital and seniority.

As well, we study worker flows as a function of intensity of regulatory activity to assess if worker flows in the aggregate can shed light on different views of the revolving door.

The challenge

The main obstacle in studying worker flows between the regulatory and private sector is lack of available data. A large literature in labour economics has studied direct job-to-job flows (Blanchard and Diamond 1990, Fallick and Fleischman 2004), and more closely to this paper, inter-industry job transitions (for example, Artuc et al. 2010) employing longitudinal and cross-sectional data surveys. However, because banking regulators account for only a tiny fraction of all US workers, none of these sample surveys is detailed enough to construct worker flow statistics for the regulatory sector. Political scientists have also taken up the challenge of investigating this phenomenon and industrious non-profit groups, such as the Centre for Responsive Politics, have attempted a systematic overview of the US revolving door phenomenon.1 However, the data in such endeavours – at least currently – also appear too sparse.

We circumvent this challenge by constructing a unique dataset of career paths of more than 35,000 former and current regulators across all regulators of commercial banks and thrifts – the Federal Reserve Banks (Fed), the Federal Depository Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Office of Comptroller and Currency (OCC), the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), and state banking regulators – that have posted their curricula vitae on a major professional networking website. Our sample spans the past 25 years and provides a unique perspective into the process of selection and transition of personnel from these regulatory agencies to the private sector. Our approach to construct worker transitions is new in the literature and, more generally, offers an original avenue towards the study of employer-employee matched data sets (for example, Abowd et al. 2008), which are typically hard to come by in labour economics. After contrasting shortcomings and strengths relative to standard labour data surveys, we study worker flows both in the aggregate, and at the worker level using panel regressions.

Basic facts on worker flows between the banking regulatory and private sector

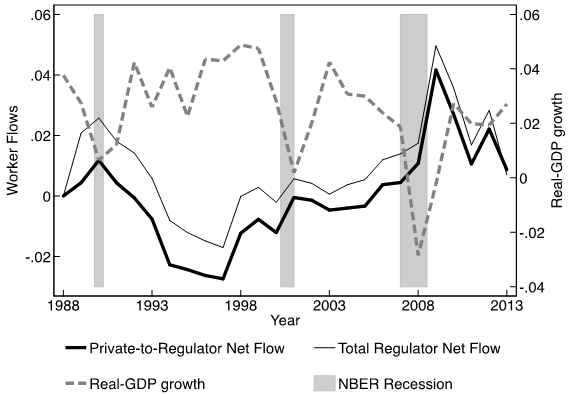

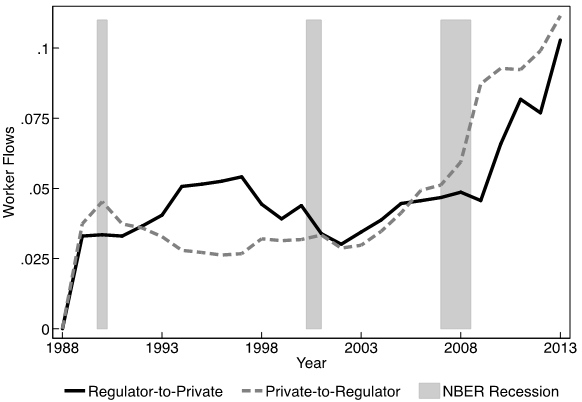

Our data reveal clear evidence of countercyclical net worker inflows into the regulatory sector. Net worker flows from the private sector to the regulatory sector fall significantly and are often negative in good times, which may be the result of higher gross inflows to the regulatory sector in bad times or higher gross outflows in good times (see Figure 1). Looking at the data, we find that higher gross outflows to the private sector during economic booms are a key driver of the countercyclical regulator net worker flows (i.e. banking regulators move to Wall Street when the economy is booming). We also find evidence of higher gross inflows in regulation in bad times as well as in the past few years, likely due to strong regulatory demand linked to enhanced banking supervision following the post-2007 financial turmoil (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Net worker flows into regulatory sector

Note: This figure plots net worker flows (measured on the left-scale) against macroeconomic conditions as measured by real GDP annual growth rates (dashed line) and NBER recessions (shaded vertical areas). Net private-to-regulator worker flows (thick solid line) are defined as the share in each year of all workers in our sample that transition from the private sector to the regulatory sector, less the share of transitions out of the regulatory and into the private sector. We also show total net-regulator flows (thin solid line), which include transitions in and out of the regulatory sector to the private sector, as well as to student status and to unemployment.

Figure 2. Gross worker flows into and out of regulatory sector

Note: This figure shows gross worker flows against macroeconomic conditions as measured by NBER recessions (shaded vertical areas). Gross private-to-regulator worker flows are defined as the share in each year of all workers in our sample that transition from the private sector to the regulatory sector. Gross regulator-to-private worker flows are defined as the share in each year of all workers in our sample that transition from the regulatory sector into the private sector.

We investigate in more detail the potential sources of inflows and outflows from regulatory jobs by assessing the relationship of worker flows with relative demand-side proxies for job-creation or destruction in the banking and regulatory sectors. Job creation in the regulatory as compared to the banking sector is likely to be positively related to measures of banking stress and inversely related to bank profitability, with opposite patterns expected for job destruction. Indeed, after controlling for aggregate economic conditions, net regulatory inflows tend to be higher in periods and in states where local banks have lower ROAs, higher non-performing loan ratios, as measured from Call Reports, and higher occurrences of bank failures. Overall, we find regulatory job mobility to be much lower than in the private sector. On average, gross-worker flows between the regulatory and private sector is less than half the job-to-job transitions in the private sector as measured from a benchmark sample we employ and data from the Current Population Survey (CPS).

Next, using information obtained from the workers’ CVs and the fact that our dataset is longitudinal, we examine the selection of individuals into and out of the regulatory sector by assessing which individuals enter and exit banking regulation over the business cycle, as a function of their human capital (i.e. their education levels, as typically listed on a CV) and skills/connections (i.e. their seniority in the regulatory organisation based on occupation).

- We find that the best talent, as proxied by higher human capital, has shorter spells inside regulatory agencies because of higher outflows to the private sector. We also find that more senior staff, not surprisingly, spends more time in regulation.

While we find no significant differences in the business cycle sensitivity across different human capital levels, overall, the regulatory sector appears to face a retention challenge when it comes to individuals with higher human capital based on their shorter regulatory spells. Consistent with this finding, we also find that regulatory spells have been declining in the past 25 years. For example, while about 88% of workers that started working in regulation in 1988 spent three or more years working in regulatory agencies, only 64% of workers that started working did so two decades later.

‘Quid-pro-quo’ and ‘regulatory schooling’ hypotheses

The final part of our analysis explores aggregate regulator mobility as a function of regulatory actions. According to one prominent view (the ‘quid-pro-quo’ view), future employment opportunities in the private sector affects, as a quid-pro-quo, the strictness of actions of a regulator while the individual is employed in the regulatory sector. This hypothesis implies that we should observe lower gross outflows from regulation to private banking during periods of high enforcement activity (or, conversely and more intuitively, that laxity while working in regulation should be followed by an exit to the private sector, possibly in the form of a cushy job, as quid-pro-quo).

An alternative view of the revolving door (the ‘regulatory schooling’ view) suggests that regulators may instead have an incentive (or at least not a disincentive) to favour complex rules because ‘schooling’ in these regulations enhances regulators future earnings, should they transition to the private sector. Such a hypothesis would imply high gross inflows into regulation at times of higher regulatory intensity as workers are schooled in the new rules as well as high gross outflows from regulation into the private sector as regulators earn returns from schooling in the new rules. According to the regulatory schooling view, inefficiencies may derive not from laxity, but on the contrary – from more complex regulations.

In order to shed light on these hypotheses, we relate worker flows to intensity of supervisory activity in the data. We measure each regulator’s strictness using their formal enforcement activity in a given state and year and focus on the most severe of these actions – terminations or suspensions of deposit insurance as well as cease-and-desist orders and prompt corrective action directives, for which failure to comply are all grounds for receivership. While enforcement activity is not a measure of regulatory complexity per se, as discussed in Agarwal et al. (2014), the final impact of rules on regulated entities is the result of both regulations and the manner in which these are enforced through supervisory activity.

- Empirically, we find a positive association between the intensity of strict actions over time and across states and the net inflows into the regulatory sector.

Looking more closely at gross flows, we find that this relationship is driven by more inflows into regulatory jobs in periods of high enforcement/more intense regulatory activity. Gross outflows from the regulatory sector are, in fact, higher around periods of higher enforcement activity. We find similar patterns when we focus on cross-state variation only by including time-fixed effects, implying that our results are not just capturing movements in aggregate economic conditions.

Our evidence on higher gross inflows and outflows during periods of more intense regulatory activity are consistent with the regulatory schooling view and inconsistent with the quid-pro-quo channel. On the one hand, we should note that our tests on this dimension are limited due to availability of regulator specific proxies of enforcement activity or of regulatory complexity. We therefore caution against taking these findings as establishing a conclusive assessment of whether quid-pro-quo or regulatory schooling leads to regulatory distortions. That said, this evidence is consistent with findings on the positive relationship between regulatory strictness and regulators’ turnover into the private sector provided for state banking supervisors in the US as discussed in Agarwal et. al (2014).

Discussion

Our findings speak to the debate on the design of rules concerning revolving doors. Critics of the regulatory revolving door have proposed restricting the ability of regulatory personnel to transition to the private sector, which under federal law (see 12 U.S.C. § 1820k) is subject to a one-year ‘cool-off’ period for any compensation – as an employee, officer, director, or consultant – with a previously supervised institution. There have also been discussions to further tighten the hiring of industry insiders by regulatory agencies. Such arguments, while no doubt important, ignore other important positive aspects of the revolving door, such as its potential to enhance the ability of regulatory agencies to hire better quality workers. Our results suggest that the regulatory sector faces a retention challenge, as measured by the lower employment spells of regulatory personnel in more recent years and for workers with higher education. While more work is needed to quantify the regulatory distortions induced by the revolving door, our findings do suggest that tightening the revolving door without altering other aspects of worker incentives may further create challenges for regulatory agencies to seek and retain talent. Rather than seeing our study as definitive work on the regulatory revolving door, we hope our work will spur more interest in an area that is begging for more research.

References

Abowd, J, F Kramarz and S Woodcock (2008), “Econometric Analyses of Linked Employer-Employee Data,” in L. Mátyás and P. Sevestre, eds., The Econometrics of Panel Data (The Netherlands: Springer), pp. 727-760.

Agarwal, S, D Lucca, A Seru, and F Trebbi (2014), “Inconsistent Regulators: Evidence from Banking”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(2): pp.889-938.

Artuç, E, S Chaudhuri, and J McLaren (2010), “Trade Shocks and Labor Adjustment: A Structural Empirical Approach”, American Economic Review, 100(3): 1008-45.

Blanchard, O J and P Diamond (1990), “The Cyclical Behavior of the Gross Flows of U.S. Workers,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2, 85–155.

Fallick, B and C A Fleischman (2004), “Employer-to-Employer Flows in the U.S. Labor Market: The Complete Picture of Gross Worker Flows,” FEDS Working Papers 2004-34, Federal Reserve Board.

Johnson S and J Kwak (2010), 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown, Published by Random House Inc.

Lucca D O, A Seru, and F Trebbi (2014), “The revolving door and worker flows in banking regulation”, NBER working paper No. w20241.

Footnote

1 https://www.opensecrets.org/revolving/