The evidence is clear: parental socioeconomic status (SES) – Including parents’ education, employment, or income – remains a major determinant of children’s lifelong health (Björkegren et al. 2021, Black et al. 2019, Currie 2008). In both rich and poor countries, children of parents from lower-SES backgrounds are more likely than their peers to suffer from ill health during childhood, which in turn can lead to lower education, income, and poor health in adulthood (Strauss and Thomas 2008). The strong association between SES and health (or ‘gradient’) hampers individual wellbeing and economic development. Therefore, it is key to understand when the SES gradient emerges, how it evolves over childhood, and, most importantly, if children that are born and grow up in disadvantaged family backgrounds can catch up, at least partially, in terms of their health. These are key questions for policies to alleviate the SES gradient in health and break the intergenerational cycle of poverty.

To understand this in a recent paper (Aurino et al. 2022), we study the relationship between parental SES and children's heights from birth to young adulthood by using high-quality individual data from a large number of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Click or tap here to enter text.We focus on height, instead of other commonly used measures such as self-reported health status, for different reasons. Height is relatively easy to measure objectively and available for both children and adults in LMICs. Height is also a good measure of overall health that correlates with other health outcomes, such as disease incidence and mortality, and it is an important predictor of economic outcomes in adulthood (Fogel 1994, Steckel 2009). Finally, transmission of low height from parents to their children is one of the drivers of substantial persistence in SES inequalities in human capital across generations (Akbulut-Yuksel and Kugler 2016, Behrman et al. 2017).

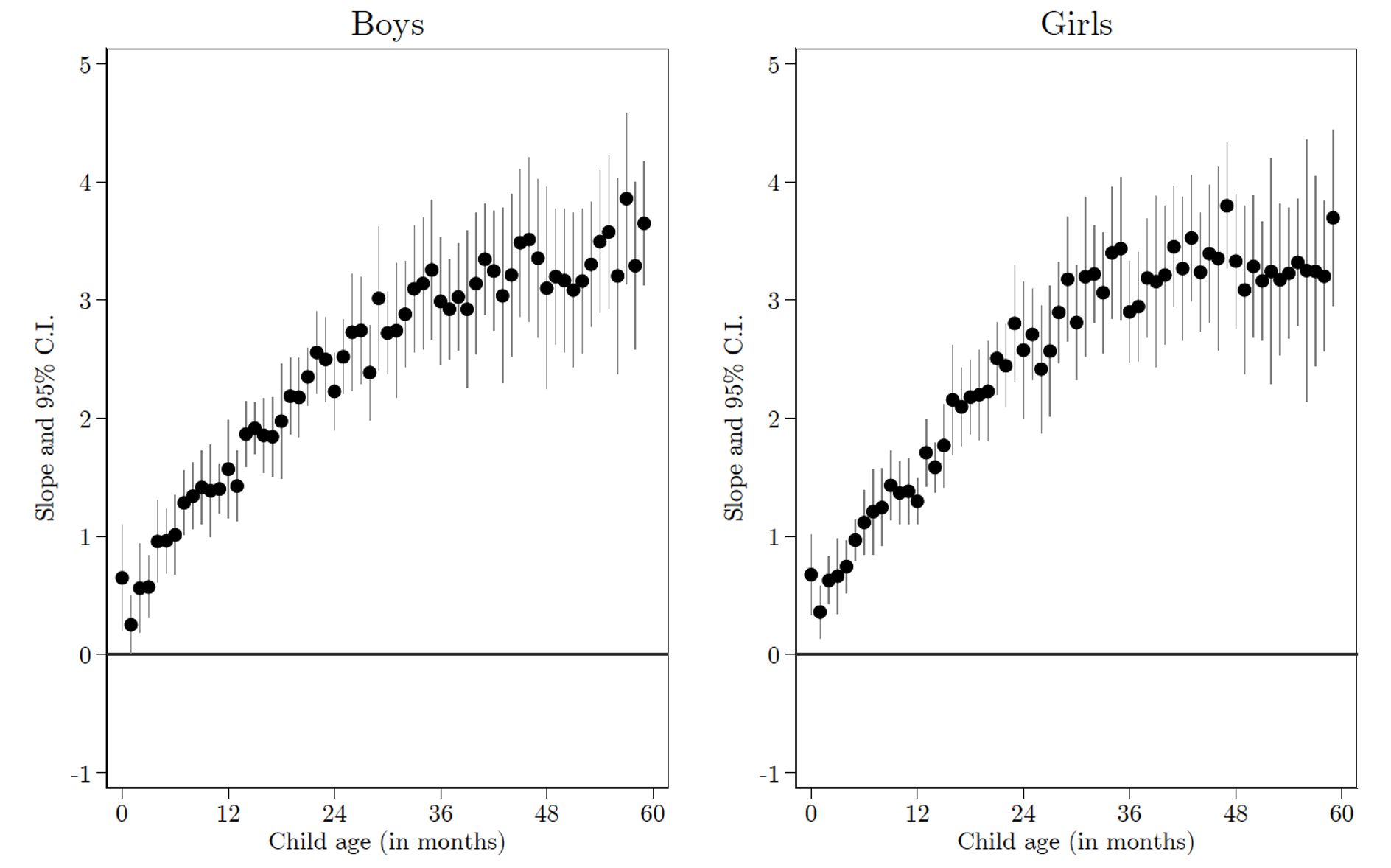

We show that the age profile of the relationship between child height and maternal education – our preferred measure of SES – follows an inverted-U shape: the gradient increases until adolescence and then progressively declines, although it remains positive once adult height is achieved. To document these patterns, we proceed in steps. First, we study how the gradient changes with age in early childhood by using high-quality data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Our sample includes information from 1.6 million children under five years of age born in 1981–2018 in 73 LMICs. In these data, the cross-sectional association between child height and maternal schooling is small and insignificant at birth but it increases steeply between birth and age five (Figure 1).

Figure 1 DHS: Child height versus maternal education

Source: Authors’ calculations from DHS data.

Note: For each age (in months) the figure shows the point estimate and a 95% confidence interval of the slope of a regression, estimated with ordinary least squares, of child height (in cms) on a dummy variable equal to one if the mother has completed at least secondary education. Total sample size is n = 1,556,034.

Although the DHS data do not include height for children older than five, most surveys record height of women from the age of 15 onwards. For adolescents who have not yet left their family of origin, it is possible to link their height to their mother's education. In this (potentially selected) sample of adolescents, the association between height and maternal education, while still substantive and statistically significant, is much smaller than for five-year-olds. This suggests that the gradient increases monotonically until a certain age but then declines.

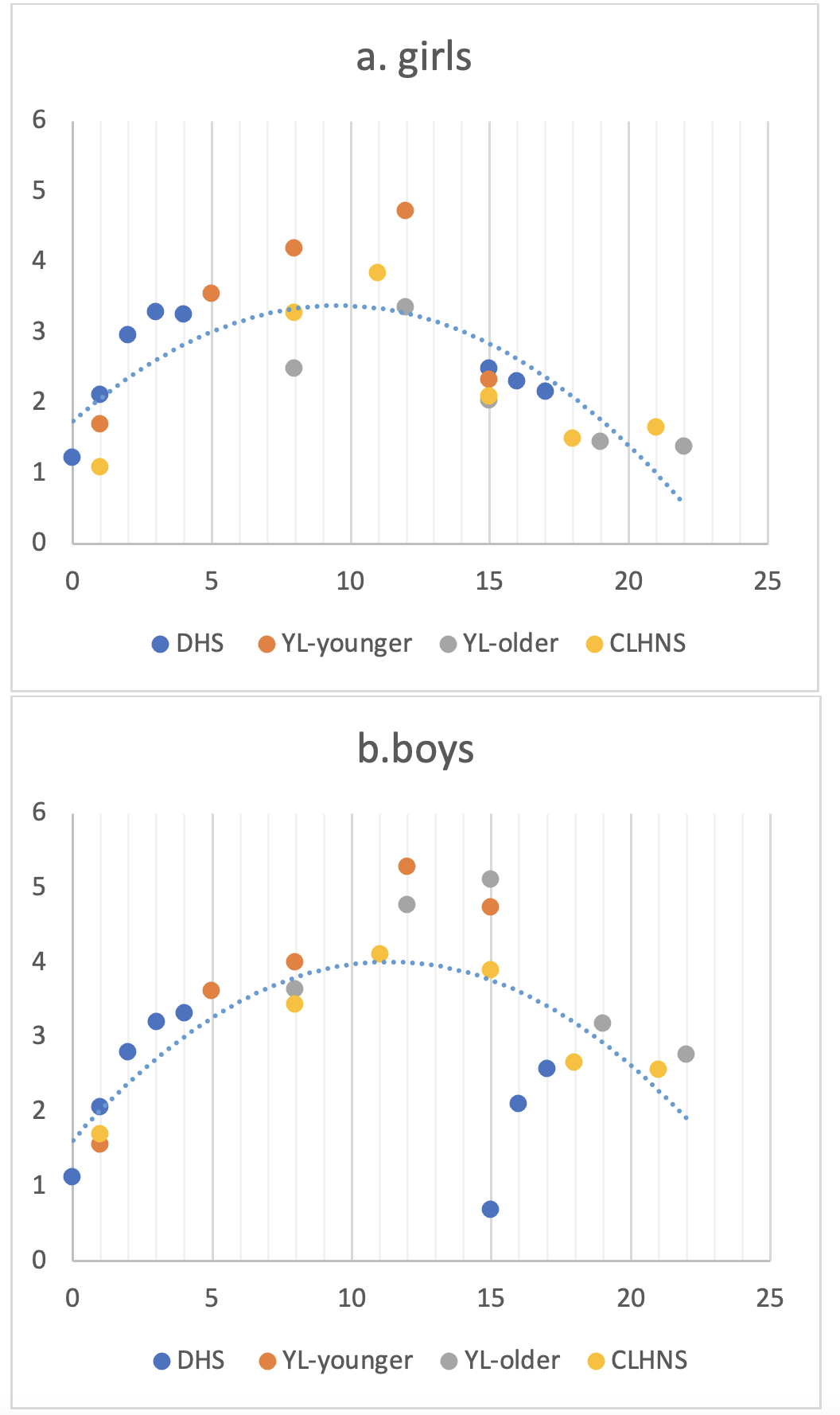

To better assess the age profile of the gradient, we use longitudinal data from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam from the Young Lives study (Barnett et al. 2013) and from the Philippines' Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey (CLHNS) (Adair et al. 2011). These high-quality data include repeated height measurements for a sample of about 15,000 children, many of which were followed from birth (or shortly afterwards) until early adulthood. As in the DHS sample, these longitudinal data show that the association between height and SES (the ‘gradient’) follows an inverted U-shape, increasing at first but then decreasing around the pubertal growth spurt (Figure 2). Our findings are very similar if we use alternative measures of SES, or if we replace raw height with standardised height-for-age ‘z-scores’.

Figure 2 The rise and fall of the SES-height gradient

Source: Authors’ calculations from the DHS data covering 73 different countries from 1981 to 2018, the Young Lives (YL) covering Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam, and the CLHNS covering Cebu (Philippines).

Notes: “YL-Younger” and “YL-Older” cohorts refer to two separate cohorts of children followed in YL. For each age the Figure shows the point estimate of the slope of a regression, estimated with ordinary least squares, of child height (in cms) on a dummy variable equal to one if the mother has completed at least secondary education. The blue dotted line shows an estimated 2nd order polynomial that uses the gradients at all ages and from all data sets.

What may be driving the evolution of the gradient as an inverted U? There may be biological and behavioural mechanisms at play. With regards to the former, we hypothesise that, for both boys and girls, the inverted U-shape of the gradient may be explained by the link between SES and the onset and duration of the adolescent growth spurt (AGS): low-SES children reach the peak of their AGS when high-SES are already past theirs, allowing them a degree of height catch-up. This hypothesis is based on two documented patterns. First, in many countries the well-established secular decline in the age at menarche among girls is linked to overall improvements in socioeconomic conditions (de Muinck Keizer-Schrama et al. 2001, Pathak et al. 2014, Prentice et al. 2010). Age at menarche and SES are also negatively associated in low-income settings, as documented in the Philippines (Adair 2001) and confirmed in our data. Second, it has been observed that low-SES children achieve on average their adult height at older ages (Bozzoli et al. 2009, Steckel 1986). Based on these insights, we propose and estimate a new model to describe the shape of the height growth curve with low frequency longitudinal data. Findings from the model strongly support the hypothesis that lower-SES children start their AGS later than higher-SES peers, and continue growing taller until a later age.

What about behavioural responses? We hypothesise that taller adolescents may start adult life earlier in ways that may be detrimental to further growth in stature. For instance, taller boys may start working at younger ages, and taller, sexually mature girls may marry and have children at a younger age. Previous research shows that the age at menarche predicts marriage rates and education levels among girls (Field and Ambrus 2008). Such behavioural responses may impose a ‘nutritional cost’ that could be detrimental to physical growth, and could explain the inverted U-shape pattern if they matter differently for children of low versus high SES. However, when we test hypotheses, we find limited supporting evidence.

Our results highlight the role of adolescence as a window of opportunity for catch-up in health outcomes. We show that height gaps between low- and high-SES children in our large sample narrow during and after adolescence. This is consistent with earlier literature showing that the potential for catch-up growth increases with delayed maturation and a longer growth period (Martorell et al. 1994, Simondon et al. 1998). Thus, our evidence adds to a growing body of work highlighting the importance of adolescence as a key period for human capital investments (Akresh et al. 2012, Andersen et al. 2021, Carneiro et al. 2021, van den Berg et al. 2014) , in addition to the in-utero and the early years (Conti et al. 2022).

References

Adair, L S (2001), “Size at birth predicts age at menarche”, Pediatrics 107(4): E59.

Adair, L S, B M Popkin, J A Akin, D K Guilkey, S Gultiano, J Borja, L Perez, C W Kuzawa, T McDade and M J Hindin (2011), “Cohort Profile: The Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey”, International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3): 619.

Akbulut-Yuksel, M and A D Kugler (2016), “Intergenerational persistence of health: Do immigrants get healthier as they remain in the U.S. for more generations?”, Economics and Human Biology, 23, 136–148.

Akresh, R, S Bhalotra, M Leone and U O Osili (2012), “War and stature: Growing up during the Nigerian civil war”, American Economic Review, 102(3): 273–277.

Andersen, S H, L Steinberg and J and Belsky (2021), “Beyond early years versus adolescence: The interactive effect of adversity in both periods on life-course development”, Developmental Psychology, 57(11): 1958–1967.

Aurino, E, A Lleras-Muney, A Tarozzi and B Tinoco (2022), “The Rise and Fall of SES Gradients in Heights around the World”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17344. https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=17344

Barnett, I, P Ariana, S Petrou, M E Penny, L T Duc, S Galab, T Woldehanna, J A Escoba, E Plugge and J Boyden (2013), “Cohort profile: The young lives study”, International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(3): 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys082

Behrman, J R, W Schott, S Mani, B T Crookston, K Dearden, L T Duc, L C H Fernald, and A D Stein (2017), “Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty and Inequality: Parental Resources and Schooling Attainment and Children’s Human Capital in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 65(4): 657–697. https://doi.org/10.1086/691971

Björkegren, E, M Lindahl, M Palme and E Simeonova (2021), “Why educated parents have healthier children: Environmental versus genetic factors”, VoxEU.org, 11 March. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/why-educated-parents-have-healthier-children-environmental-versus-genetic-factors

Black, S, P Devereux, P Lungborg, and K Majlesi (2019), “Nature versus nurture in economic outcomes and behaviours”, VoxEU.org, 16 May. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/role-nature-versus-nurture-wealth-and-other-economic-outcomes-and-behaviours

Bozzoli, C, A Deaton, and C Quintana-Domeque (2009), “Adult height and childhood disease”, Demography 2009 46:4, 46(4): 647–669. https://doi.org/10.1353/DEM.0.0079

Carneiro, P, I L García, K G Salvanes, and E Tominey (2021), “Intergenerational Mobility and the Timing of Parental Income”, Https://Doi.Org/10.1086/712443, 129(3): 757–788. https://doi.org/10.1086/712443

Conti, G, P Ekamper, and S Poupakis (2022), “The long-lasting health effects of severe shocks during pregnancy”, VoxEU.org, 21 February. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/long-lasting-health-effects-severe-shocks-during-pregnancy

Currie, J (2008), “Parents’ health, children’s health and incomes: a cycle of poverty”, VoxEU.org, 19 July. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/child-health-and-intergenerational-transmission-human-capital

de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S M P F, D Mul, C Sultan et al. (2001), “Trends in pubertal development in Europe”, APMIS, 109(S103): S164–S170. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1600-0463.2001.TB05762.X

Field, E and A Ambrus (2008), “Early Marriage, Age of Menarche, and Female Schooling Attainment in Bangladesh”. Journal of Political Economy, 116(5): 881–930. https://doi.org/10.1086/593333

Fogel, R W (1994), “Economic Growth, Population Theory, and Physiology: The Bearing of Long-Term Processes on the Making of Economic Policy”, American Economic Review, 84(3): 369–395. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118058

Martorell, R, L K Khan, and D G Schroeder (1994), “Reversibility of stunting: epidemiological findings in children from developing countries – PubMed”, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 48(Suppl 1): S45-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8005090/

Pathak, P K, N Tripathi, and S v Subramanian (2014), “Secular trends in menarcheal age in india-evidence from the Indian Human Development Surveypa”, PloS ONE, 9(11), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111027

Prentice, S, A J Fulford, L M A Jarjou, G R Goldberg, and A Prentice (2010), “Evidence for a downward secular trend in age of menarche in a rural Gambian population”, Annals of Human Biology, 37(5): 717–721. https://doi.org/10.3109/03014461003727606

Simondon, K B, F Simondon, I Simon, A Diallo, E Bénéfice, P Traissac and B Maire (1998), “Preschool stunting, age at menarche and adolescent height: a longitudinal study in rural Senegal”, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 52, 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600577

Steckel, R H (2009), “Heights and human welfare: Recent developments and new directions”, Explorations in Economic History, 46(1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EEH.2008.12.001

Steckel, R (1986), “A Peculiar Population: The Nutrition, Health, and Mortality of American Slaves from Childhood to Maturity”, The Journal of Economic History, 46(3): 721–741. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/cupjechis/v_3a46_3ay_3a1986_3ai_3a03_3ap_3a721-741_5f04.htm

Strauss, J and D Thomas (2008), “Health over the Lifecourse”, in J Strauss and D Thomas (eds), Handbook of Development Economics (Vol. 4), Elsevier Science.

Van den Berg, G J, P Lundborg, P Nystedt, P, and D-O Rooth (2014), “Critical Periods During Childhood and Adolescence”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 12(6): 1521–1557. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12112