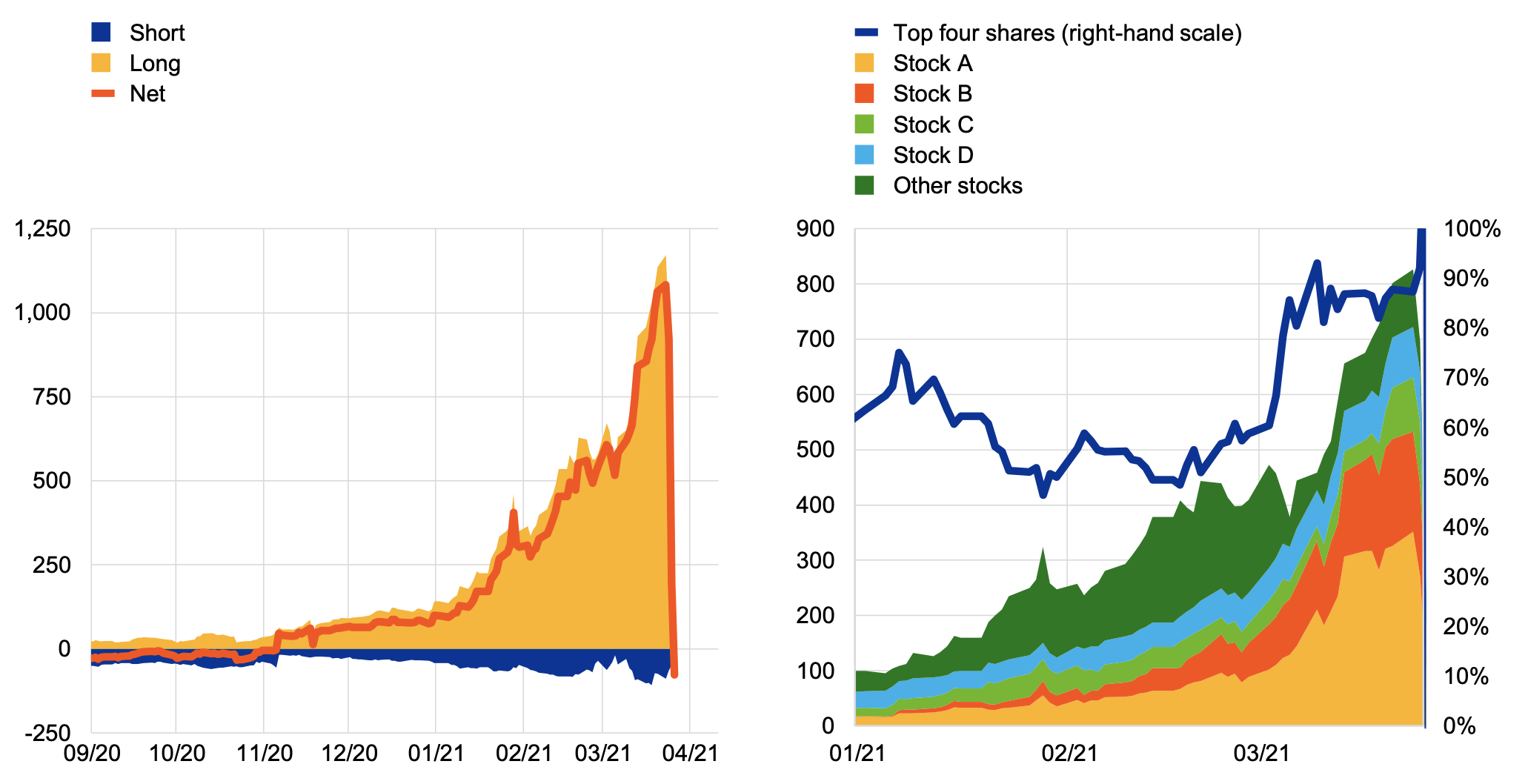

Since 2008, the share of credit intermediation performed by non-banks included in the monitoring universe of the report (investment funds and 'other financial institutions’) has markedly increased.

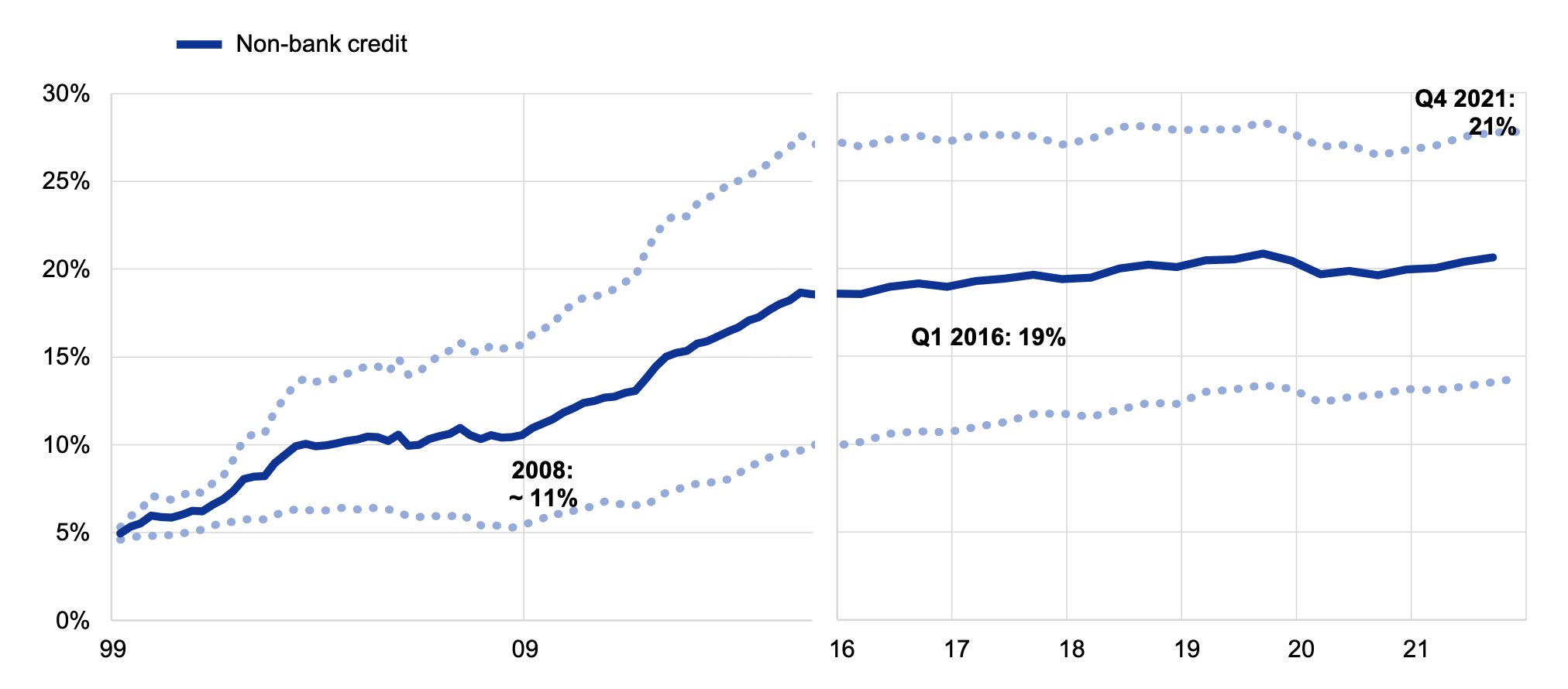

Credit provided by non-banks in the form of loans and debt securities accounted for 20% of credit to euro area non-financial corporates (NFCs) at the end of 2021, compared with 11% a decade ago (Figure 1). A more important role for non-banks in financing NFCs provides benefits to the real economy as firms can diversify their sources of funding and reduce their reliance on bank credit. By providing an alternative source of funding to bank credit, non-banks contribute to efficiency and overall resilience of the financial system, because a wider range of funding sources helps to share financial risks. This can make the financial system less vulnerable to shocks.

Figure 1 Non-bank credit in percentage of euro area non-financial corporations (NFC) credit provided by all financial institutions

(percentages of NFC credit from financial institutions)

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts, balance sheet item statistics, financial vehicle corporation statistics) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Non-bank credit reflects the relative share of the investment funds and other financial institutions in providing debt financing to euro area NFCs compared with credit provided by all financial institutions (the non-bank financial sector and banks), in the form of loans or debt securities. The solid line reflects an average of the dotted lines, which include (dotted line at the top) or exclude (dotted line at the bottom) loans granted by a residual of other financial institutions. The methodology is the same as described in Box 2 of ECB (2022), but insurance corporations and pension funds are excluded.

However, non-banks can also present risks to financial stability. Investment funds offering daily redemptions to investors while investing in asset classes that are not always reliably liquid such as corporate bonds or emerging market debt might face a liquidity mismatch (Goldstein et al. 2017, d’Avernas et al. 2020). This risk can crystallise when investors redeem their shares en masse and markets are unable to absorb asset sales from funds smoothly. Such liquidity strains were seen in March 2020 for some open-ended funds (FSB 2020) and for money market funds (ESRB 2021). In the context of an expected rise in rates, bond funds might face losses on their portfolio which could trigger large outflows of investors. The use of excessive leverage by non-banks, such as hedge funds, financial vehicles engaged in securitisation, or financial corporations engaged in lending, could further magnify shocks, as market shocks can lead to larger losses for leveraged entities and their counterparties in case of default.

In our 2022 report (ESRB 2022), we analyse these risks in more details.

Risks of a disorderly correction for EU bond funds

Over the last few years, EU bond funds have shifted their portfolios towards longer-dated securities, thereby increasing their exposure to interest rate risk. Against a backdrop of low interest rates, EU bond funds increased the weighted average maturity of their assets from 7.5 years in 2018 to 9.2 years in 2021. Securities of longer maturities usually carry a term premium that enables bond funds to partly offset falling (or low) interest rates. At the same time, prices of longer-term bonds are typically more sensitive to changes in interest rates, as measured by the duration.

A sharp increase in interest rates would lower the prices of fixed rate bonds, resulting in mark-to-market losses for bond funds with a high exposure to interest rate risk. Valuation losses could trigger investor outflows, requiring bond fund managers to sell securities already subject to downward pressure on prices due to rising yields. Funds can use interest rate derivatives (IRDs) to hedge their bond portfolio or increase their exposure to interest rate risk. If they use the IRDs for hedging, the mark-to-market losses resulting from the rise in interest rates, and the consequent investor outflows could be smaller. Funds using IRDs to increase their exposure to interest rate risk, however, would face margin calls on their derivative positions if interest rates increase. In this case, the derivatives exposures may exacerbate potential vulnerabilities.

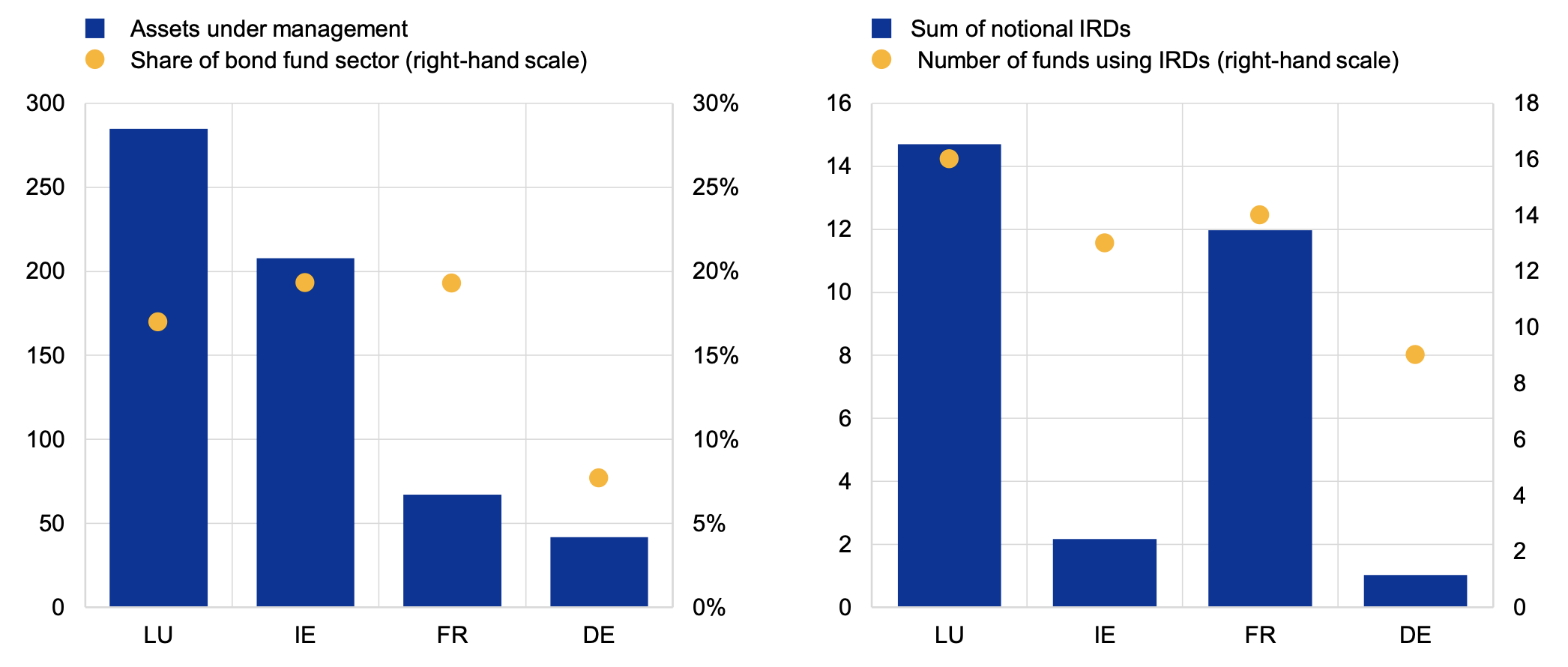

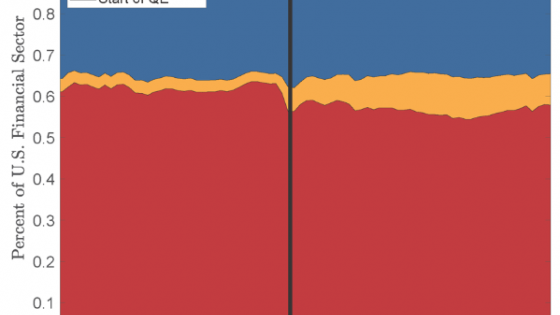

In one the special features of our report (ESRB 2022), we simulate the impact of a parallel shift of 100 basis points across the yield curve, using a sample of the largest 200 bond funds across four EU jurisdictions (Luxembourg, Ireland, Germany, and France) with around €600 billion of total assets (Figure 2). Portfolio data are combined with supervisory data on funds’ IRD exposures from EMIR. Overall, 52 bond funds use IRDs with a gross notional exposure of close to €30 billion (Figure 3).

Figures 2 and 3 Bond funds in the sample: size (left panel) and the use of IRDs (right panel)

(Figure 2: €billions (left-hand scale) and percentages (right-hand scale); Figure 3: €billions (left-hand scale))

Sources: EMIR, Refinitiv Lipper, Bloomberg, and ESRB calculations.

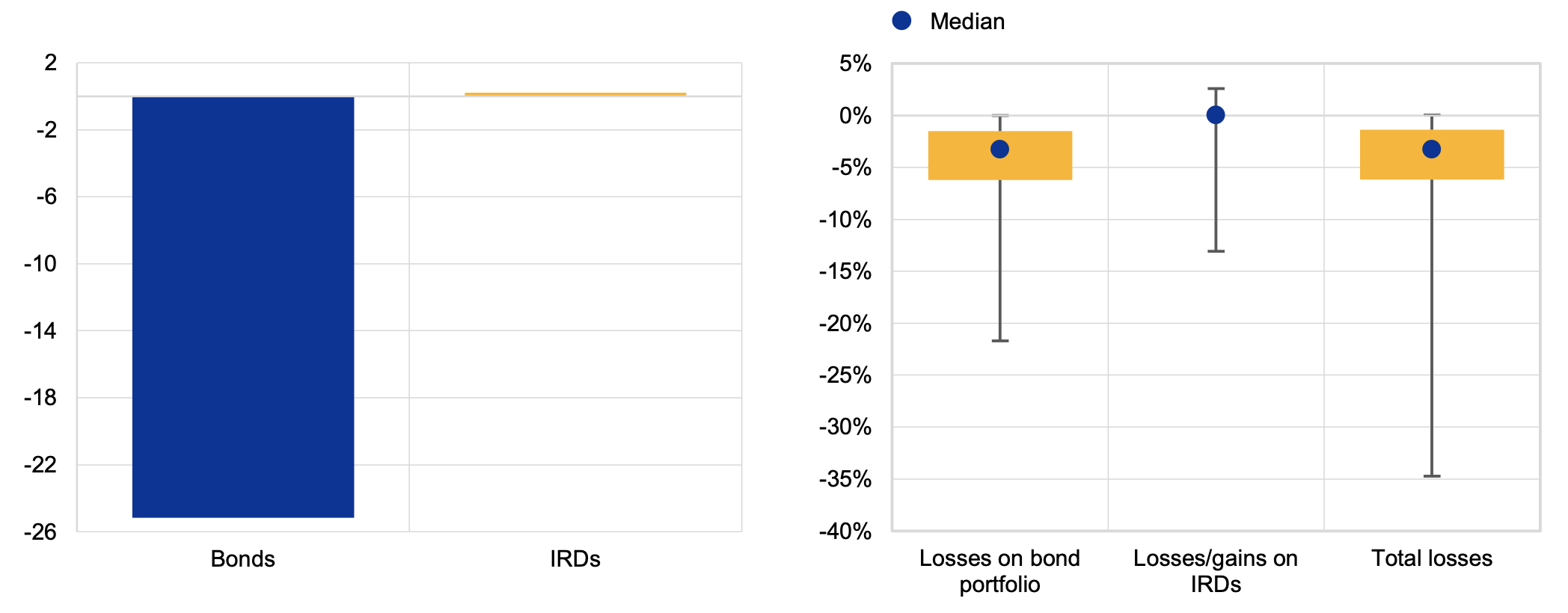

Overall, a parallel shift of 100 basis points across the yield curve would result in valuation losses of around 4% of net asset value (NAV), although the impact varies widely by fund. On aggregate, a rise of 100 basis points would yield around €25 billion in mark-to market losses on the bond portfolio and a net profit of around €210 million on IRDs (Figure 4). The small positive gain from IRDs stems from the small size of IRDs held by funds in our sample (only 52 funds out of 200) and the fact that most funds use IRDs to hedge their interest rate risk, resulting in mark-to-market gains on derivatives that would partially compensate losses on bond portfolios. Still, for one fund, the bond valuation losses would be amplified by derivatives: losses on IRD positions would be higher than 10% of NAV, resulting in overall losses of 35% of total assets (Figure 5).

Losses from an initial interest rate shock could trigger outflows with potential non-linear and second-round effects. The losses on the bond portfolio range from 0% up to 22% of total assets, with more than one-third of funds facing losses higher than 5% of total assets and around 20% of funds facing losses above 7% of total assets. Such a decline in the value of bond funds could lead to large outflows, since based on the flow-return relationship, investors tend to redeem from underperforming funds. Should funds need to sell less liquid assets to accommodate these outflows amid low liquid holdings, a negative spiral of losses and further outflows could begin, amplifying the negative market dynamics.

Figures 4 and 5 Losses resulting from a 100 basis point interest rate hike: total (left panel) and distribution (right panel)

(Figure 4: €billions; Figure 5: percentages of net asset value)

Sources: EMIR, Refinitiv Lipper, Bloomberg and ESRB calculations.

Excessive use of leverage by non-banks

Excessive leverage is a general cause for concern in financial markets, and in non-bank finance, too, it can cause considerable disruptions. The March 2021 collapse of Archegos in the US was a case in point. Archegos, a US family office, defaulted on margin calls from derivatives counterparties, resulting in more than $10 billion of losses for counterparty banks. Since Archegos performed derivatives trades with EU counterparties, EMIR data can be used to track the build-up of positions by the US family office.

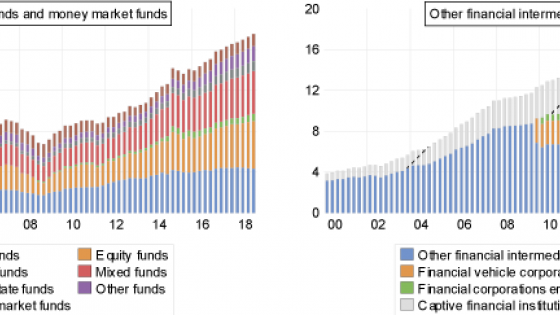

Over the years, Archegos pursued an investment strategy focused on long positions in a few stocks, mainly in the technology sector. Instead of purchasing stocks to gain exposures to the securities, Archegos used equity swaps that were sold by several banks, replicating similar exposures across a range of counterparties. These contracts allowed the firm to obtain leverage through synthetic prime brokerage,

magnifying profit and losses based on the performance of the underlying stocks.

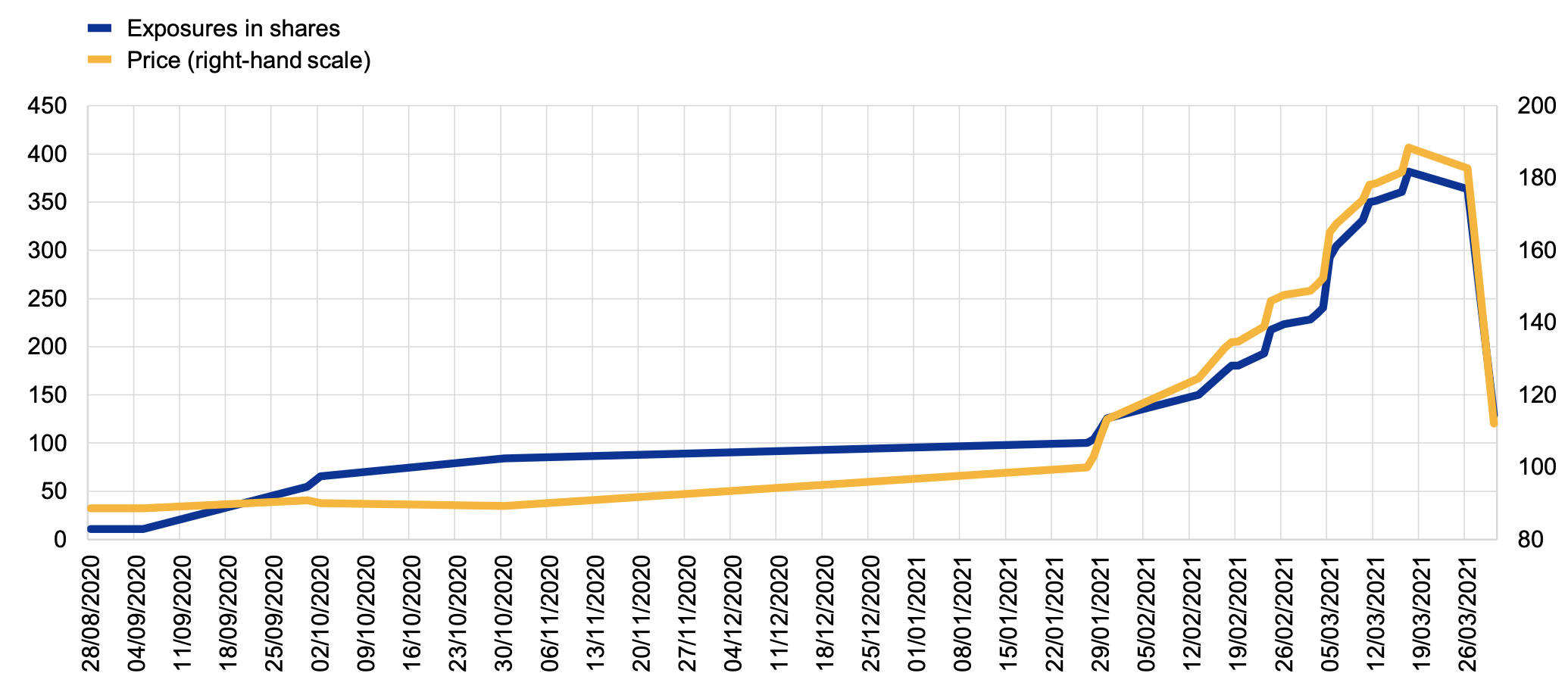

In 2020 Archegos increased its exposures to total return swaps, with notional amounts for some contracts surging over that period. In addition, EEA30 data show a steep increase in exposures in February and March, with notional exposures increasing by more than 460% between mid-January and mid-March. EMIR data also indicate that Archegos had highly concentrated long positions in a few technology stocks such as stock A (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Archegos exposures to stock A via equity swaps with EEA30 counterparties and equity price of stock A

(values rebased at 100 = 27 January 2021)

Sources: EMIR, Refinitiv Datastream, and ESMA.

A sharp drop in the stock prices of firms to which Archegos was synthetically exposed to along with high leverage precipitated its collapse. On 22 March, the price of stock A declined by 6.7% and kept declining throughout the week, as did other stocks which were important in the Archegos portfolio (Figures 7 and 8). The large decline in stock prices led to an abrupt change in the value of Archegos swaps and to large variation margins being requested by counterparties. When Archegos defaulted, the dealer counterparties had to liquidate their underlying long positions in the stocks, since the banks were no longer hedged. Because Archegos’ market footprint was substantial in those stocks – with the firm synthetically owning more than 20% of the shares of some companies – large sales by dealers aggravated the decline in prices, leading to substantial losses for some of the dealers, especially those who were slower to liquidate their positions.

This episode illustrated how excessive leverage can propagate shocks to the financial system. While leverage remains moderate for most EU non-bank entities, close monitoring remains warranted for some entities such as hedge funds, and some jurisdictions are considering setting up leverage limits for some type of funds, such as real estate funds in Ireland (Central Bank of Ireland 2021). The analysis also demonstrates that regulatory reporting under EMIR can be used to monitor systemic risk and inform macroprudential policy decisions.

Figures 7 and 8 Mark-to-market value of Archegos’ total return swaps (left panel) and long exposures (right panel)

(values rebased at 100 = 31 December 2020)

Sources: EMIR and, ESMA.

Note: Data for EEA30 countries.

Addressing the risks and vulnerabilities

As early as 2017, the ESRB had issued a recommendation (ESRB 2017) aimed at limiting fund leverage and other risks in the fund business, including:

- Better alignment between redemption policies and investment strategy for open-ended investment funds that invest in inherently less liquid assets, like real estate, loans or certain corporate bonds

- Access to data to allow more comprehensive risk assessment

- Further operationalisation of macroprudential leverage limits for alternative investment funds

The case of Archegos, even if it originated outside the EU and in an unregulated entity, is a strong reminder of the latent risks at work around leverage in non-bank finance. It underlines that the 2017 ESRB recommendations are more relevant than ever before and should be given due consideration as the EU is reviewing the AIFMD and UCITS regulatory frameworks for the EU fund industry.

Authors’ note: Any views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official stance of the ESRB, ESMA, its member institutions, or any institution to which the authors may be affiliated.

References

Abad, J, M D’Errico, N Killeen , V Luz, T Peltonen, R Portes and T Urbano (2017), “Mapping the interconnectedness between EU banks and shadow banking entities”, VoxEU.org, 25 April.

Bank of England (2017), “Hedge funds and their prime brokers: developments since the financial crisis”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Q4 2017.

Bouveret A and M Haferkorn (2022), “Leverage and derivatives — the case of Archegos”, TRV Risk Analysis, ESMA.

Central Bank of Ireland (2021), “Macroprudential measures for the property fund sector”, Consultation Paper 145.

d’Avernas, A, Q Vandeweyer and M Darracq-Pariès (2020), “The growth of non-bank finance and new monetary policy tools”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

ECB (2022), “Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area”, ECB Committee on Financial Integration.

European Systemic Risk Board (2017), “Recommendation of the European Systemic Risk Board of 7 December 2017 on liquidity and leverage risks in investment funds”, ESRB/2017/6.

European Systemic Risk Board (2021), “Issues note on systemic vulnerabilities and preliminary policy consideration to reform money market funds (MMFs)”.

European Systemic Risk Board (2022), “EU Non-bank Financial Intermediation Risk Monitor”.

Financial Stability Board (2020), “Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil”.

Goldstein, I, H Jiang and D Ng (2017), “Investor flows and fragility in corporate bond funds”, Journal of Financial Economics 126(3): 592-613.

Hodula, M (2020), “Off the radar: The rise of shadow banking in Europe”, VoxEU.org, March.