Cross-border river pollution is a common issue worldwide and it is a great challenge for regulators to mitigate water pollution, especially in developing countries. When polluters are located in the same administrative jurisdiction, local regulations may be sufficient to balance the respective benefits and costs. However, when an administrative border separates these parties, local regulators may fail to consider the portion of damages which accrue to water users in downstream jurisdictions, resulting in excessively lenient regulations. Due to this dynamic, firms may choose (or be encouraged) to locate near jurisdictional boundaries so that the bulk of their pollution damages consist of such spillovers.

Existing policies have failed to resolve the border effect, since nearly all of these new regulatory instruments are applied at the locality level rather than at the firm level, while firms are susceptible to border effects. By strategically relocating polluters towards boundary areas through differential regulation, local governments can improve their local environmental quality for any given quantity of pollution, at a cost to downstream areas. This phenomenon is prevalent in China (Cai et al. 2016, Zhang et al. 2018) and other countries (Gray and Shadbegian 2004, Helland and Whitford 2003), as well as between countries (Sigman 2002, Wolf 2007). Although the problem is widely understood, few effective solutions have been offered. Existing studies have provided investigation of China’s environmental regulations (e.g. Fan et al. 2020 on the effect of China’s enforced environmental policies since its 11th Five-Year Plan on industrial firms), but few studies raise effective solutions for the border effect.

In order to improve the water quality of the downstream length of the Xin’an River, in 2011 China established the first inter-jurisdictional ecological compensation mechanism in the Xin’an River Basin, the Ecological Compensation Initiative (ECI), designed to facilitate upstream–downstream cooperation in water pollution regulation. A fund was set up and jointly financed by the central government (contributing 300 million RMB per year) and two provinces: Anhui Province (100 million RMB) and Zhejiang Province (100 million RMB). The two provinces made an agreement on compensation for the ecological services provided by Anhui Province to clean the river water. As a base payment, the 300 million RMB from the central government would be paid to Anhui in support of its water conservation. If Anhui attained the agreed-upon cross-border water quality target based on the pollution reading at the border – one that exceeds federally mandated standards – Zhejiang would pay 100 million RMB to Anhui to compensate its inputs into water quality control; otherwise, Anhui would pay 100 million RMB to Zhejiang for ecological loss due to its failure in upstream water protection.

Figure 1 Reduction in wastewater discharge of prefectures around the Xin’an River Basin after 2011

Notes: The red line shows the Xin’an River and the green dot marks the river boundary between Anhui Province and Zhejiang Province. Colours show the percentage reductions in wastewater discharge in 2011–2013 relative to 2008–2010.

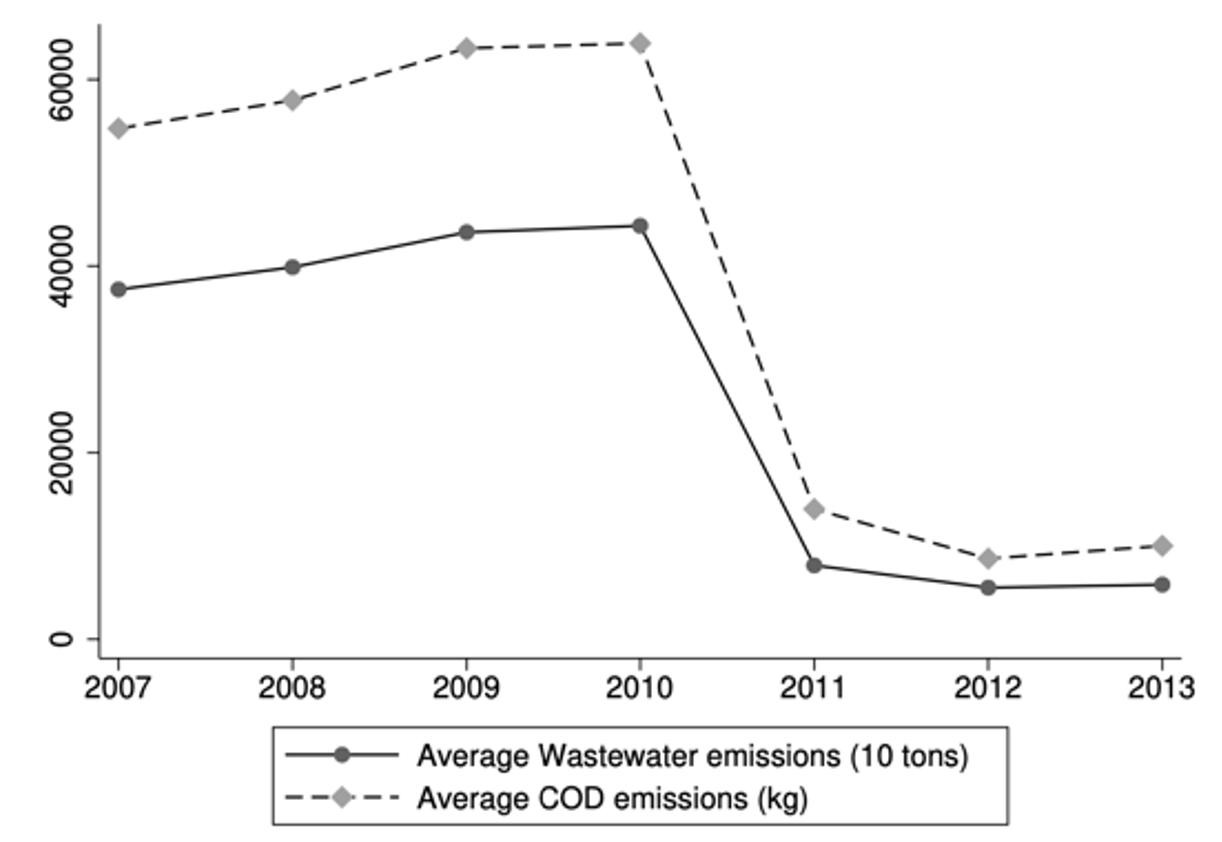

The ECI brought about favourable changes to cities’ water pollution levels, as shown in Figure 1. Prefectures located closer to the Xin’an River have reduced their water pollutants by a greater proportion since the initiative has been implemented. As the target cities, Huangshan Prefecture and Jixi County in upstream Anhui have larger proportional reductions than Hangzhou Prefecture, which is further downstream, while the areas adjacent to target cities did not show signs of having reduced pollution. The significant reduction in pollution is also observed in firm data, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Water pollutant emissions from Anhui firms along the Xin’an River from 2007 to 2013

Based on these facts, we build a theoretical model to illustrate how the ECI facilitates local governments taking into account spillover effects and tighten regulation of firms near the river border. Following Lipscomb and Mobarak (2016), we model a river of unit length which separates into two segments governed by two jurisdictions, with households as well as firms distributed along the river with some density function. The local governments choose production at each point along the river within their jurisdiction to maximise social welfare, which includes the utility gains from consumption and the utility losses from the river pollution generated during production, based on firms’ production functions and emission functions.

In our model, we compared the border pollution under maximisation choices without the ECI and the pollution level at the border after the ECI was implemented. The main point is that under the ECI, whether the upstream government may receive the compensation fund depends on whether the level of pollution at the border satisfies the contract level, therefore involving border pollution in social welfare upstream and motivating the upstream government to make an optimal choice for the whole river basin. The border pollution determines the spillover pollution borne downstream, which is not considered by the upstream government without ECI. The ECI may prompt the upstream jurisdiction to internalise pollution externalities at the river border into its maximisation problem, thereby incentivising the upstream government to tighten the regulation of the river border. From the model, we raise the propositions that there exists a mutually acceptable compensation arrangement under which both upstream welfare and downstream welfare increase relative to the no-contract case, and the compensation arrangement induces the upstream jurisdiction to reduce its pollution through decreased output.

Empirically, we find solid evidence of the effectiveness of the ECI. We employ a difference-in-differences strategy to study the effect of this watershed ecological compensation mechanism by utilising firm-level pollution data from the Annual Environmental Survey of Polluting Firms. We find that China’s implementation of the ECI is positively associated with an increased probability of upstream firms reducing water pollution after 2011, and that the effect could be explained by both scale effects and technique effects. As for the underlying mechanisms, we show that upstream firms reduced total water and fresh-water inputs, increased pollution treatment facilities, and lowered water pollution generated during production processes.

We then attempt to reveal the heterogeneity of the policy effect caused by uneven enforcement within an area due to the harm from pollution differing depending on proximity to the river. We examine the heterogeneous effect across firms at different distances from the river boundary and the bank of the river tributary, due to possible variation brought about by geographic distance. We find that the effect of the ECI is stronger for firms located closer to the provincial border and to the river tributary.

Next, we extend our discussion to examine more implications of this new approach to addressing cross-border externalities. As the ECI clearly focuses on specific target areas (i.e. Huangshan Prefecture and Jixi County in upstream Anhui Province), it is plausible that firms might react by migrating to nearby, less-regulated areas. We find a significant increase in firm exits from the focal areas and a significant increase in entry of industrial firms to neighbouring prefectures. These results indicate that firms tend to leave areas executing the ECI and relocate to neighbouring areas with comparatively more lenient regulations, which, to a certain extent, verifies an ‘internal’ variant of the polluting havens hypothesis. Consistent with this, we also find evidence of larger water pollution increases in areas where more firms entered.

Finally, to investigate whether this compensation arrangement could be used in other places, and to identify determinants that might account for its effectiveness in this region, we examine cross-provincial compensation schemes in nine other watersheds across China.1 We find that similar arrangements also effectively reduce water pollution from the upstream prefectures, confirming the broader applicability of arrangements similar to the Xin’an ECI. The ECI also induces more firms to exit from the upstream markets and impedes firms’ entry to these markets. Moreover, these results are significantly driven by greater wealth in downstream prefectures relative to upstream prefectures, perhaps reflecting some arbitrage between differences in the marginal utility of income across locales. The region’s economic structure also influences the effectiveness of the ECI: upstream prefectures with less reliance on industrial production and a larger proportion of tourism saw sharper reductions in water pollution.

An important takeaway from our study is that the ECI as a semi-market regulatory tool combines characteristics of both traditional command-and-control and market methods, which makes it effective at handling cross-border spillover effects under the scenario that the downstream stakeholders and the upstream ecological service providers are massive and dispersed. Our findings suggest that bilateral compensation for ecosystem services appears to successfully reduce pollution and that upstream jurisdictions are willing to reduce their net income (after subtracting output losses and adding ECI payments) in exchange for reduced pollution, as the theory suggests. Although previous studies indicate that the bargaining between upstream and downstream parties may be inefficient due to the large transaction costs associated such bargaining (Dinar 2006, Sigman 2002), our results suggest that the ECI may be a promising model for cases in which jurisdictional boundaries are nested within a larger national jurisdictional authority that can nudge the parties toward a Coasian solution.

References

Cai, H, Y Chen and Q Gong (2016), “Polluting thy neighbor: Unintended consequences of China’s pollution reduction mandates”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 76: 86–104.

Chen, S, J S G Zivin, H Wang and J Xiong (2022), “Combating Cross-Border Externalities”, NBER Working Paper No. w30233.

Dinar, S (2006), “Assessing side-payment and cost-sharing patterns in international water agreements: The geographic and economic connection”, Political Geography 25(4): 412–437.

Fan, H, J S G Zivin, Z Kou, X Liu and H Wang (2020), “Going Green in China: Firms’ Responses to Stricter Environmental Regulations”, VoxChina, 29 April.

Gray, W B and R J Shadbegian (2004), “‘Optimal’pollution abatement—whose benefits matter, and how much?”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 47(3): 510–534.

Helland, E and A B Whitford (2003), “Pollution incidence and political jurisdiction: evidence from the TRI”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 46(3): 403–424.

Lipscomb, M and A M Mobarak (2016), “Decentralization and pollution spillovers: evidence from the re-drawing of county borders in Brazil”, The Review of Economic Studies 84(1): 464–502.

Sigman, H (2002), “International spillovers and water quality in rivers: do countries freeride?”, American Economic Review 92(4): 1152–1159.

Wolf, A T (2007), “Shared waters: Conflict and cooperation”, Annual Review of Environmental Resources 32: 241–269.

Zhang, B, X Chen, and H Guo (2018), “Does central supervision enhance local environmental enforcement? Quasi-experimental evidence from China”, Journal of Public Economics 164: 70–90.

Endnotes

1 China has promoted the ECI to other pilot river basins since 2015, and by 2019 nine other cross-provincial river basins had implemented this ecological scheme between upstream and downstream provinces.